Chanting mantras in a serene and self-composed tone, he finally subdued the rolong.

Dangbo..o..o Dingbo..o..o.. there was a trader who lived with his wife and his daughter. He often made long trading trips to Tibet and India. Now it happened that he had to make a journey to India to replenish his stock of salt. He wanted to have his stock of salt in time for the rice harvest so that he could exchange it for grain which he would then take to Tibet and thereby increase his profits even further.

After days of preparations he was ready to start his journey. The pack mules were well fed and strong, and their saddles had been repaired or replaced as needed. His food provisions were packed and his little tent was folded neatly and ready. Then he counted out his silver coins and was satisfied. He was sure he would have a successful trade. He bade farewell to his wife and daughter and began his journey southwards to India.

As the days passed the rice was harvested and eaten or bartered but the trader did not return. Days grew into months and still he did not come. As more time passed the mother and her daughter became increasingly concerned. They were now quite convinced that something terrible had happened to him. The trader had made meticulous preparations for his journey but in those days there was nothing he could do to prevent himself from contracting the fatal satpa or malaria which killed many people from the highlands when they dared to descend to the heavily forested plains where malaria was endemic. The satpa had killed him too.

One evening all the dogs in the village started to wail and howl in the most strange way and soon the mother and daughter could hear the father calling for them, but from the way the dogs barked, they knew that it was only his rolong or his corpse that had revived after death and was possessed by a malevolent spirit. So they hid in the roof truss. The father tried to come into the house but as he was only a rolong he could neither bend his head nor lift his feet to cross the threshold and he kept on banging his head against the beam above the door and hitting his feet against the threshold. After a long time he was finally able to stumble into the house. The two women had to hold their hands over their mouths to prevent themselves from screaming on seeing the rolong in front of them. For what they saw was a horrific image of the man they used to know and love. There stood an ash-gray naked man with his eyes fallen deep into their sockets. His nose was bare bone, and there was no flesh over his gums. His hair stood on end. They scrutinized him from head to toe. There were mustard flowers between his toes which must have been caught there as he shuffled through the mustard fields near the village. His movements were slow, stiff and awkward as his joints were locked in rigor mortis. Once in the house he began to look for his wife and daughter everywhere. He went to the fireplace and blew into the embers to start a fire but only maggots fell out of his mouth, for a rolong has no breath. It is said that rolongs will try to transform as many living human beings into rolongs as possible. They can do this by simply touching the human beings on the head. He began to search the house for his wife and his daughter, but before he could find them the roosters in the village cried, “Cockerico, cockerico, cockerico,” and he left, for rolongs become simple corpses after the first cock crow. As he left the house he muttered, “Let’s say that you won today.”

The mother and daughter worried the whole day because they knew that he would come again. As darkness fell the dogs started to bark in that strange way again and sure enough he came. The mother and daughter hid under a pile of nine zangs or huge water storage containers which were turned upside down, one on top of the other. The rolong seemed to struggle for a long time to get into the house but when he did he headed for the pile of zangs and in his awkward slow movements, he began to turn them up one by one. Before the last zang could be turned the village rooster called, “Cockerico, cockerico, cockerico,” and the rolong had to leave again, muttering angrily, “Let’s say you won again.”

The next evening they hid under nine layers of baskets. The rolong came and turned up the baskets one by one but before he could turn the last basket the first rooster called and they were saved once again. Now the mother and daughter were terrified, for they knew that he would not leave them until he had transformed them into rolongs. So they decided to run away. They carried whatever belongings they could carry and left the village quietly so as not to raise an alarm. On the way they happened to meet an old ragged chodpa. They stopped to talk with him and when he asked them why they were leaving the village, they told him the whole story. The chodpa explained to them that the rolong would follow them wherever they went so it was no use running away. He advised them that as long as the phowa rites to release his namshi or spirit from his body were not performed there was no way of getting away from a rolong. He said that even if the body of a rolong were chopped up into pieces and scattered in different places or cremated it could always come together again. He offered to come with them and to perform the rites if they were willing to return to their home. The chodpa’s quiet knowledge and his unassuming and gentle manners won the confidence of the fugitives. They placed full faith in the chodpa and returned home with him.

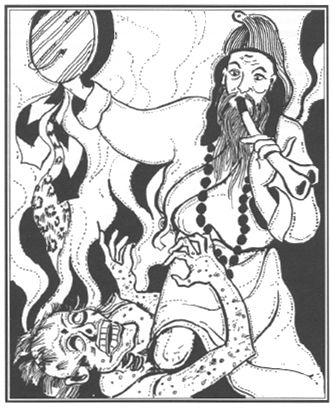

On arrival in the village the chodpa instantly began to make preparations. He gathered some pieces of bamboo, heated them over the fire, and then cut them into splinters. He also asked for some naktha or rope made of yak hair. As darkness fell, he began to perform the chod. Soon the dogs began to bark as usual and the rolong came calling for his wife and daughter. The chodpa confronted him and started to beat him with the kangdom or thigh-bone trumpet, all the time reciting the mantras of the chod. A most frightening struggle ensued. For a long time the two women feared that the chodpa would succumb to the persistent iron-like grip of the rolong, who seemed to experience neither pain nor exhaustion. Sweat poured down the chodpa’s brow but he would not give up. Chanting the mantras in a serene and self-composed tone, he finally subdued the rolong. He pinned him down on the floor. He placed his right knee on the rolong’s chest and his left on the floor. Then he blew into the thigh-bone trumpet triumphantly three times. He then drove the bamboo splinters into all the joints of the rolong’s body and tied it up with the naktha as a corpse would normally be tied up for cremation. He administered the phowa rite on the corpse, chanting the mantras and clicking his fingers as he repeated, “Phad ... phad”. The spirit of the dead was now freed and no longer vulnerable to the malevolent spirits which had lived within his body.

The woman and her daughter could now live in peace without fear and regret, for the rolong was subdued and the deceased had received the appropriate death rites.