The Battle of Savate

A signal came through instructing me to report back to our Battalion HQ at the big army base back in Rundu, a few hundred kilometres to the east. We were to begin planning another op, and all the indications were that this was to be a big one. I managed to get a lift in a Puma, this being one of the advantages of being based in the HQ! My mates in the companies were usually trooped around in the back of the huge Kwevoël trucks or in Buffels, exposed to the scorching sun and arriving covered in dust days later.

I wasn’t briefed immediately on my return. However, the next few weeks were characterised by UNITA officers and our CSI (Chief Staff Intelligence) spooks hurrying in and out of our intelligence room between meetings with Commandant Ferreira. When the OC finally briefed me so that I could draw up the signals plan, little did I know the significance of what lay ahead.

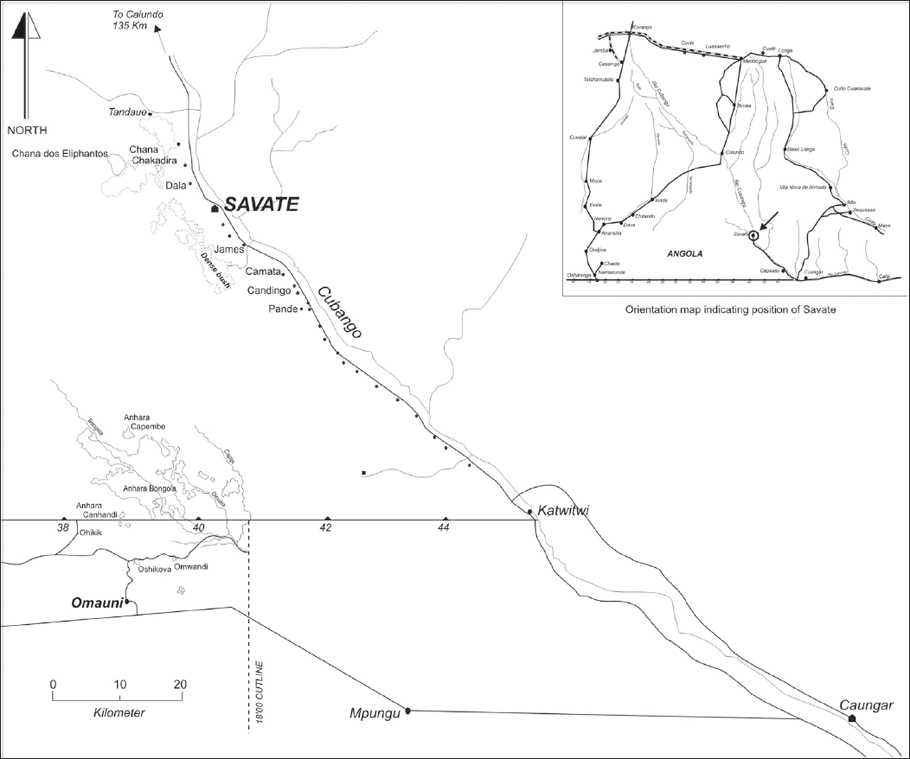

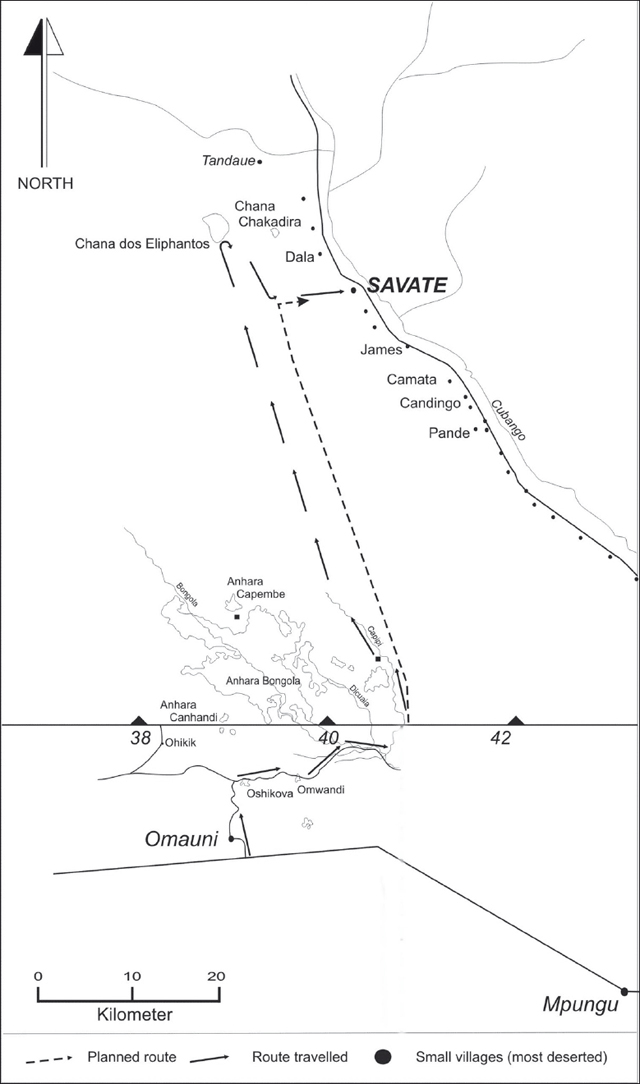

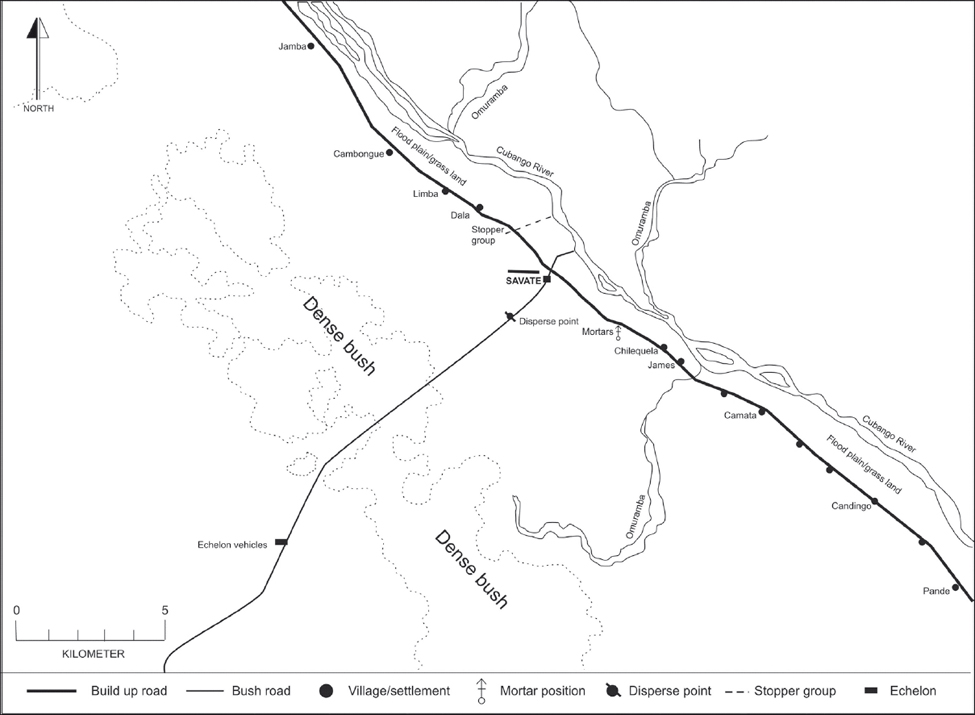

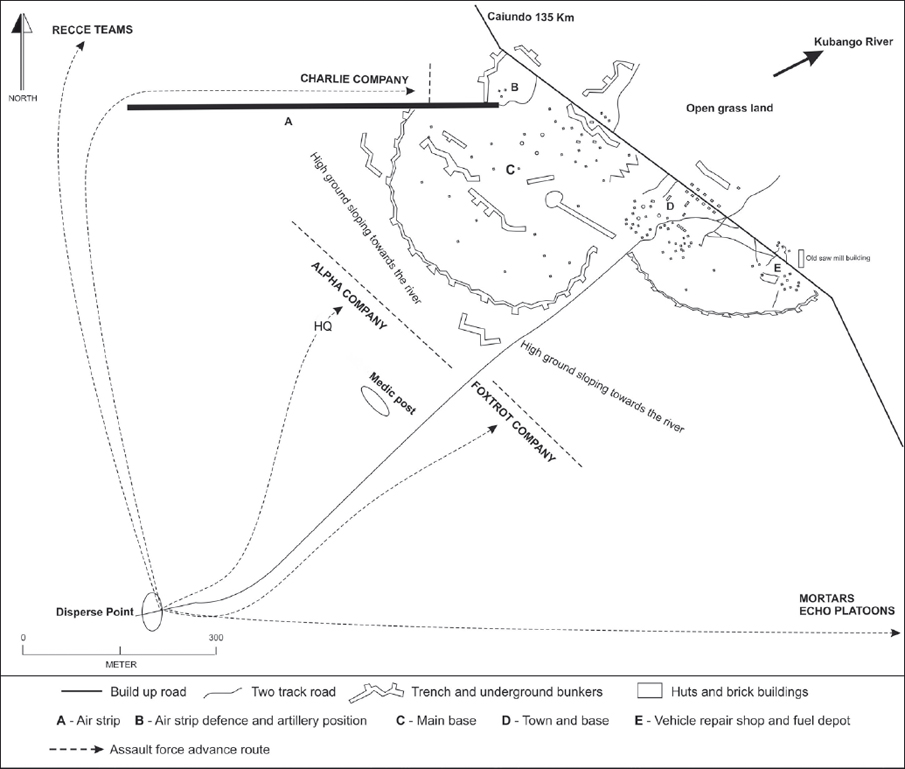

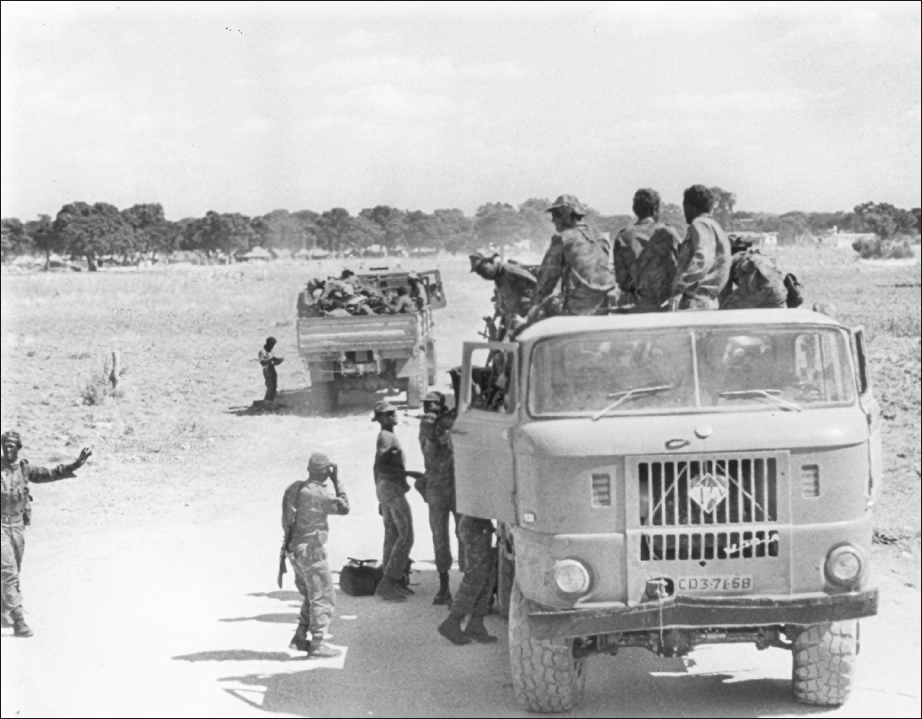

In what was code named Operation Tiro-Tiro, we were to attack some 400 Angolan army troops (MPLA) in their base at Savate approximately 80km inside Angola on the Cubango River. Our force was to be comprised of three infantry companies, a mortar platoon and our recce wing as stopper groups to the north of the base. Our numbers totalled just some 350 men, which defied the military principle of only attacking if you outnumbered the defenders by three to one. We were to have no artillery or air support as this was to be a covert operation, which we would conduct under the guise of UNITA. UNITA were a guerrilla army operating in Angola and the SADF was supporting them in their fight against the Angolan army troops. The only air support was to be one Puma helicopter for medical casevac purposes, and one Alouette helicopter gunship for an emergency. Any more support of this nature would give the game away as to the fact that we were South African troops and not UNITA. Willem Ratte was to undertake a close target recce with a four-man stick the week leading up to the attack. We were to cross the border into Angola in a convoy of Buffel troop carriers and Kwevoël lorries from the base at Omauni, moving directly north to Savate, and then use the same route out again.

My first step was to request the frequencies to be used on the HF radio networks from Brigade HQ. On being allocated six HF frequencies rangingfrom 3 MHz up to 12 MHz, I began the 24-hour testing process between Omauni and Rundu, with a radio check every fifteen minutes. This was the technique I had devised after the total failure of HF communications in the early hours of the aborted attack on the Angolan garrison at Dirico. My suspicions that the enemy were eavesdropping on our radio networks were confirmed while I was doing this testing. The best frequency for use in the early morning turned out to be one that was used by the local doctors as a radio telephone, and one which was monitored closely by the Cubans / East Germans. I had one of them taunt me about the fact that he was listening in; just after I had completed a radio check at about 3.00 am in the morning!! I shudder to think of the information the doctors were unwittingly exposing to the enemy with their daily discussions of medical and other matters.

Savate’s position in Angola. (Courtesy of Piet Nortje)

The HQ contingent took a Puma ride out to Omauni about five days prior to the attack. Final plans and preparations began. The briefing of roughly thirty officers and NCOs was held in the mess hall, a corrugated iron building with a bare concrete floor. I was called on by the OC to present the signals orders and I focused on the frequencies to be used and their associated schedules – as well as warning them not to use HF communications unless absolutely necessary, due to the possibility that their conversations could well be intercepted by the enemy and the transmissions used to get a bearing on our positions. I mentioned my experience a few days earlier with the East German while testing the frequencies and this certainly got their rapt attention!

Lieutenant Willem Ratte, Sergeant Piet van Eeden and Troopers Joao and Casomo, together with a UNITA guide, left in a small convoy of about three Buffels two or three days before the attack was due, to meet up just across the border with a CSI convoy under the command of a ‘Senhor Lobb’. The plan was for Senhor Lobb to drop them off 10km north-west of Savate. Willem’s team would then carry their folding Klepper canoes (made of a wooden frame covered in canvas) to the river and paddle down that first night to Savate. They would lie up during the day on the eastern bank, positioned on the high ground overlooking the base and then cross over the river each night to reconnoitre the enemy positions. I walked out with them to their armoured Buffels and did final radio checks with them. The big diesels roared into life and they headed up the two track road to the north … they were finally on their way and the assault on Savate had begun.

I had tested and retested the radios they carried to ensure they were working. They had daily radio schedules; times at which they would report back to us. They missed the first ‘sched’, and my signallers failed to report this to me … I, of course, was responsible for not having checked up on them. I only discovered this when they missed the second ‘sched’. We immediately put into action the back-up plan, which was to send a Bosbok spotter plane into the air to try and get comms using direct line of sight, VHF radios. My heart was in my mouth while we waited to hear back from the pilot, fearing the worst and agonising over the fact that we had missed the first radio ‘sched’.

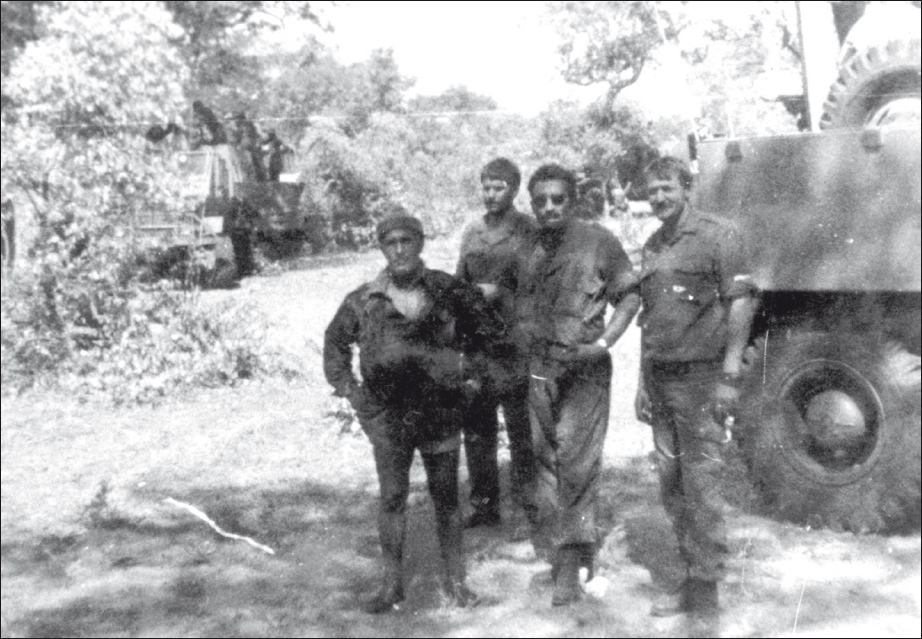

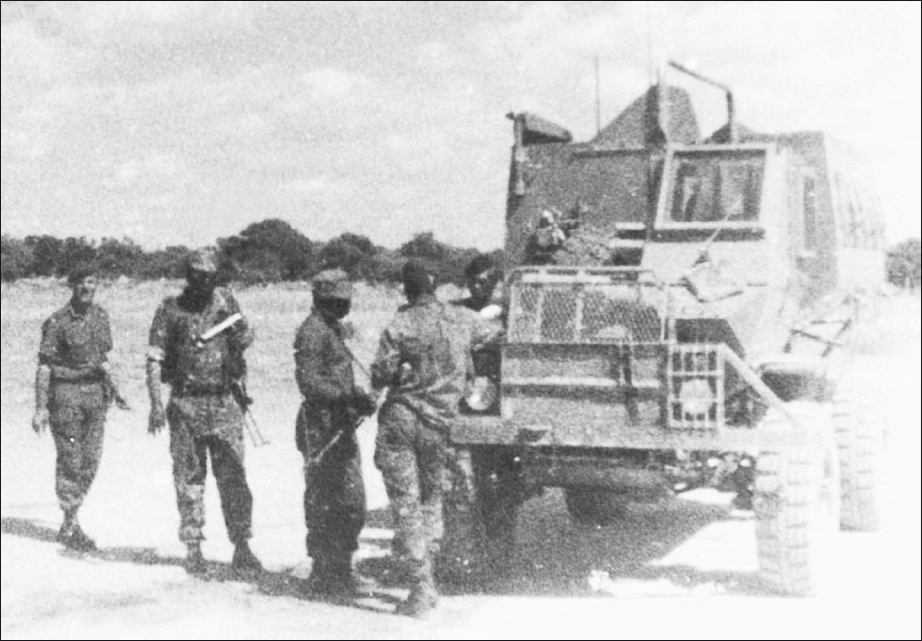

Senhor Lobb with some ‘Tiffies’ (mechanics).

The infamous Senhor Lobb, who led the convoy astray during the drive into Angola.

To calm my nerves I came up out of the sandbag-covered command bunker and stood on the earthen wall that surrounded the base, quietly looking out over the bush. I allowed my imagination to run away with me as to what might have happened to them … killed, captured, or who knew what else? Maybe if we had been onto it at the first missed radio schedule it would have been different … I laid it on for myself pretty thick! It wasn’t too long before the signaller’s head popped out from the sunken door of the command bunker to tell me that the pilot had made contact with them. It later transpired that their HF radio had got wet in the river crossings, which explained the breakdown in communication. It was with huge relief I learned that all was well with them.

Willem Ratte later told me that their UNITA guide, Senhor Lobb, had dropped them off immediately west of Savate instead of 10km to the northwest. When they had walked east towards the river, they were actually walking directly towards the base at Savate. Hearing vehicles ahead of them and thinking they were north of Savate, they skirted round to the south to get to the river. As the sun was setting, they assembled their two Klepper canoes and cautiously paddled for about 8km downriver, thinking they were heading towards Savate, when in actual fact they were going away from the base! They only realised their mistake when they came to a deserted town just before midnight and their guide identified it as a place marked on Willem’s old Portuguese road map which was actually below Savate. Willem and his team then paddled furiously back upstream for the remainder of the night in order to get back into position opposite Savate before the sun rose. This was no mean feat, especially as they had to negotiate a set of rapids in the process. As such, they lost the opportunity to recce Savate on the first night.

As the sun rose they were close to Savate but still a distance away. Exhausted, they lay up on the eastern bank of the river for the day. They eventually made it to Savate the next evening. They left their kit on the eastern side of the river again, opposite the base, and Willem and Sergeant Piet van Eeden went across and did their initial reconnaissance. Their primary objective set by Ferreira was to confirm that the enemy were still occupying the base and to obtain a rough estimate of their numbers. That the enemy were still in the base soon became very evident. In fact, it became increasingly obvious to Willem that there was far more activity in and around the base than that which could be ascribed to 400 troops. Ferreira mulled over calling off the attack, but without a firm estimate of how many troops there actually were, he decided to continue the planned operation anyway. After the attack, it transpired that there were over 1,000 enemy in the base. Had UNITA deliberately misled us by telling us that there were only 400? Had they misled us to ensure we saw the attack through?!

At long last the main convoy was ready to leave Omauni for the twoday journey to Savate. In the command Buffel were Commandant Ferreira, Captain Erasmus the Intelligence Officer, myself the Signals Officer, Sergeant Major Ueckerman the RSM, Lance Corporal Bruce Anders as my signaller and an Ops Clerk we nicknamed ‘Lappies’ (Rags). Staff-Sergeant Ron Gregory manned the Browning machine-gun mounted at the front of the Buffel. My good friend 2nd Lieutenant Tim Patrick and Corporal John van Dyk, both from the HQ intelligence unit and who reported to Captain Erasmus, were assigned to the companies as intelligence liaison. Having been confined to HQ duties since their arrival on the border, the significance of their inexperience only dawned on me after the battle. We crossed over the border and spent the first night in Angola, arriving at the ‘set-off’ point at the end of the second day.

The journey in: cheerful troops in the back of a Kwevoël, with Buffels in the background.

Savate – the route travelled by the convoy from Omauni, getting lost and finding ourselves at Chana dos Elfantos, whereafter the Bosbok spotter plane was called up to got us back on track to get to the point at which we would continue on foot. Using the aircraft posed a serious risk of compromising ourselves to the enemy. (Courtesy of Piet Nortje)

Those two days in the Buffel seemed like an eternal lifetime. Strapped into our seats in case we hit a land mine, we sat back-to-back facing outwards, five seats abreast, with the incessant sun pounding down on us. As incredible as these vehicles were in terms of their ruggedness, no one had thought to design a cover to shield the occupants from the sun. To this was added the relentless swaying and bucking of the Buffel as it ground its way along the twisting, sandy track, constantly throwing us against our shoulder straps and the kit piled up at the back of the armoured compartment which kept falling on us. Tempers became frayed and our patience with each other was stretched to the limit.

And to add to the tension in the command vehicle, the convoy got lost on the second day, compliments of the same UNITA guide, Senhor Lobb, who had dropped Willem Ratte at the wrong location a few days earlier. We had to call in the Bosbok spotter plane to get us back on track. This caused some consternation in the HQ as it may well have compromised the attack by alerting the enemy to South African activity in the area. With the Bosbok flying directly above us, Commandant Ferreira was unable to speak to the pilot using the ground-to-air VHF radio. With the ever-present experience of failed communications at Dirico lurking in his mind, he uttered a few choice expletives and hurled the handset at me. Fortunately for me it came to the end of its tether just inches from my face before bouncing back. The pilot disappeared back south again, returning a few hours later and this time we could speak to him clearly. To my satisfaction, it turned out that it had been the radio in his aircraft that was faulty and not mine. I was then able to appreciate the comical side of Ferreira’s outburst, especially after his sheepish apology.

By the end of the second day, we had arrived at the point at which we would leave the vehicles and begin the overnight march to the various positions, from which each section would launch their attack. The HQ element had a platoon of infantry attached under the command of 2nd Lieutenant ‘Trompie’ Theron to guard it. We would be coming in behind Alpha Company commanded by Lieutenant Charl Muller, with Lieutenant Jim Ross and his Foxtrot Company to our right. Charl was the Adjutant of the Battalion and was commanding Captain Tony Nienaber’s Alpha Company as Tony was away on a course. Capt Sam Heap’s Charlie Company would attack the base from the north of the airfield.

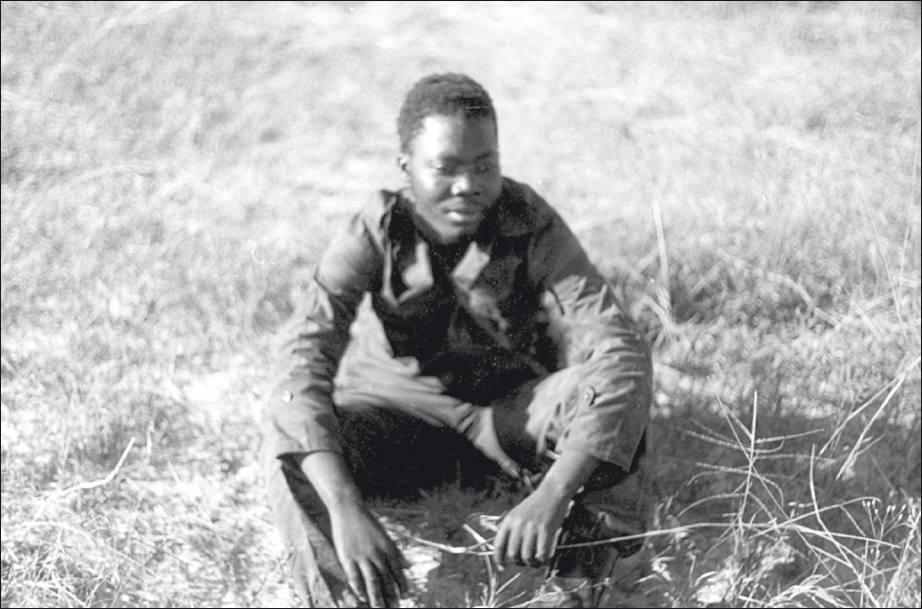

Troops resting before the long night march toward Savate.

As the sun set, the OC held his confirmatory and final Orders Group with the HQ element, the three company commanders and the mortar platoon commander. We sat on the sand amongst the tufts of grass alongside the twotrack road and he asked each of us to touch on the final pertinent points … logistics – Major Louw; intelligence – Capt Erasmus; and signals – myself. The key issue discussed was the possibility of that there were many more enemy troops than expected … yet even given this possibility, it was decided not to change the battle plan. As he summed up the latest intelligence assessment and got the opinions of the company commanders, I couldn’t help thinking that Lieutenants Charl Muller and Jim Ross certainly looked the part. To their camouflaged battle fatigues, AK-47 rifles and blacked out faces they had added their own style of headgear. Jim Ross had a dirty cloth tied over his head and knotted at the back. He was the quintessential bush fighter … still, dark, disturbing eyes and of medium height, with a squat strong physique and an aggressive temperament. Charl Muller had a dark coloured bandana tied around his head tennis player style … a lean, suave, good looking guy with a very pretty young wife back in Rundu. It was the last time I was to see him alive.

The other company commander sitting in the circle was Sam Heap. Sam was a huge guy with a hand that dwarfed mine in a handshake and a friendly demeanour that was ever ready with a broad smile. Looking around, I was pleased to be on their side in the upcoming fight. I couldn’t help thinking that it would have been good to have had Tony Nienaber with us as well … a very level-headed, dependable guy with a quiet, yet authoritative air about him.

The long night began. Everyone had just their light, first-line kit on – chest webbing with spare magazines, one day’s water and rations, grenades affixed to belts – leaving their Machillas (H frame rucksack) in the Buffels. Except for the mortar platoon, who were shouldering their heavy base plates and 81mm mortar tubes, all the troops were in first-line order. The heavy 81mm mortar bombs were initially distributed amongst all the troops, but these poor mortar buggers had to then carry the whole lot, later on in the night, the last few kilometres to their fire positions. My signaller, Lance Corporal Bruce Anders, and I were in a similar situation. In addition to our first-line kit, he and I took turns to carry the Machilla with the big HF radio, the spare Nicad batteries, handsets and everything else I thought anyone might need. All this equipment was so heavy, that to put the rucksack on we had to prop it up against a tree, thread our arms through the straps and then roll over onto our stomachs before pushing ourselves up off the sand. We then completed this complicated manoeuvre by using the tree to pull ourselves upright. We certainly had our work cut out for us that night! And Bruce was not a big guy either. Of medium height, wiry and very fit, he had been recommended to me by Willem Ratte. As an Ops Clerk back in the base at Omauni, he had seen limited time in the bush and certainly had no combat experience. He was to acquit himself well over the next few days.

We were following a two-track, sand road that led to the base. By mid-evening we had entered a thickly wooded area with tall trees that soared above us, blacking out the night sky. Through the darkness that enveloped us, we heard a heavy vehicle grinding its way towards us, and I could soon see its lights weaving through the trees. Ferreira gave the quick battle orders for only one squad to open fire on the vehicle with strict instructions to conserve ammunition. In the silence that followed the brief burst of rifle fire, we heard the left cab door crack open and someone fall out onto the grass alongside the track. He crawled off into the undergrowth and was left to his own devices, most likely to die of his wounds. As we passed the Gaz truck, I could see a dark shape on the right hand side of the cab and could smell the strong, sickly sweet smell of blood. Being left-hand-drive and with right-hand-drive vehicles back home, it was the passenger on the right-hand side and not the driver that had been shot to pieces.

Savate - the point marked ‘Echelon Vehicles’ marks where the battalion debussed, to walk through the night to the dispersal point. (Courtesy of Piet Nortje)

By the early hours of the morning we had reached the edge of the thick forest, the point from which everyone was to split up and head for their allotted kick-off points, Sam Heap to the north and the mortar platoon to the south near the river. While we moved up past some troops who had pulled over to the side of the road to let us through, I heard my friend Heinz Muller quietly call out my name in the darkness

“Justin!?”

“Heinz … .. ?”

“Jy moet lekker wees…”

Before I could answer we were gone. His tone of voice sent a chill down my spine … it was as if he was trying to tell me something. Translated literally it means “you must be well”, but it can come to mean many things depending on the tone of voice and context within which it is verbalised; from a warning to watch your step, to being encouraged to look out for yourself, or just to have fun. As I struggled along under the heavy Machilla, I thought about his comment. What puzzled me was that he seemed to be telling me to “go well” as a form of farewell. I was to have my answer during a lull in the battle ahead.

By about 2am we had reached the point from which the companies in front of us would launch the attack. The HQ element stopped under some tall trees, which stood alongside a two-track sand road that ran from the base in a southerly direction. The pale moonlight allowed us to see clearly enough, and everyone immediately fell asleep where they sat down. I went through my usual drill of setting up comms with the Tac HQ back in Omauni. Instead of slanting the wire antenna as I usually did to maximise the range, I threw the weight (an outer casing of a grenade to which the wire was attached) straight up into the tall tree above me. I was very surprised to get crystal clear communication back to Omauni some 80km away – very unusual for that time of night as it must have been about two o’clock in the morning. I soon fell asleep along with everyone else. A little later I found that I had woken myself up by having answered a radio call from Omauni, speaking to them while still asleep. Commandant Ferreira gave me a strange look before he too fell asleep again.

The sun had just risen and we were supposed to have already initiated the attack. We had been hampered by the thick forest behind us and as a result, Sam Heap’s company and the 81mm mortar guys were behind schedule. I stood up to watch Sam Heap’s Charlie Company file silently passed us to skirt to the west of the base in order to come around and attack from the north. They looked like the formidable lot that they were, quietly and purposefully filing past with their rifles held comfortably at the ready across their chests … our distinctive style. Someone waved, it could have been Sam Heap or John van Dyk but I couldn’t recognise them … they all looked the same in their ‘black-is-beautiful’ so I couldn’t distinguish any of the white guys from the troops.

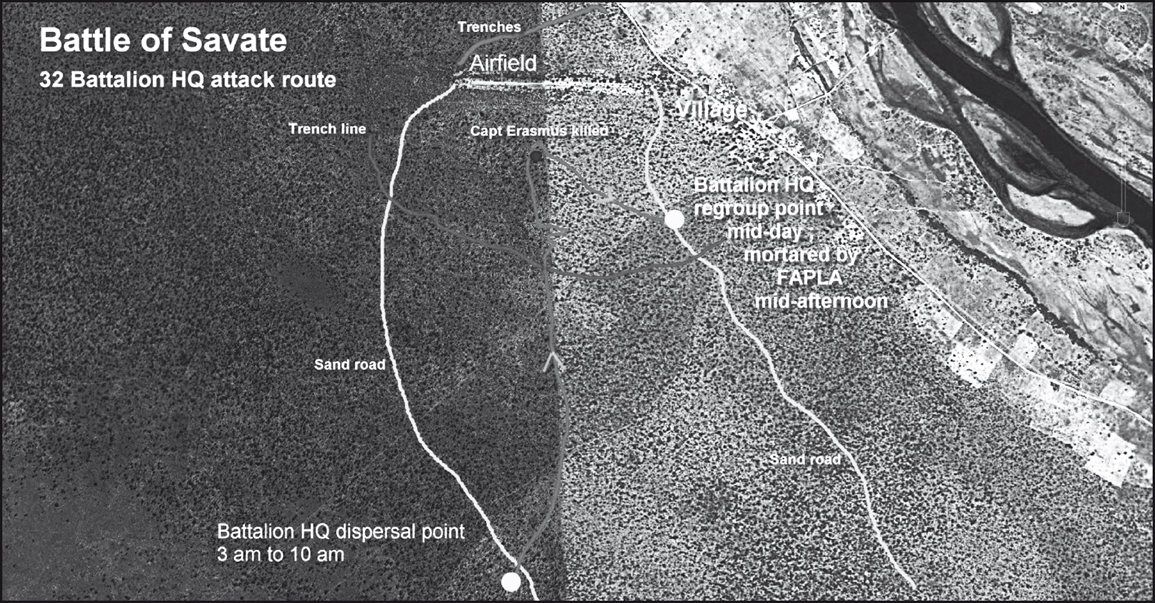

Savate – from the dispersal point marking the positions to begin the attack. (Courtesy of Piet Nortje)

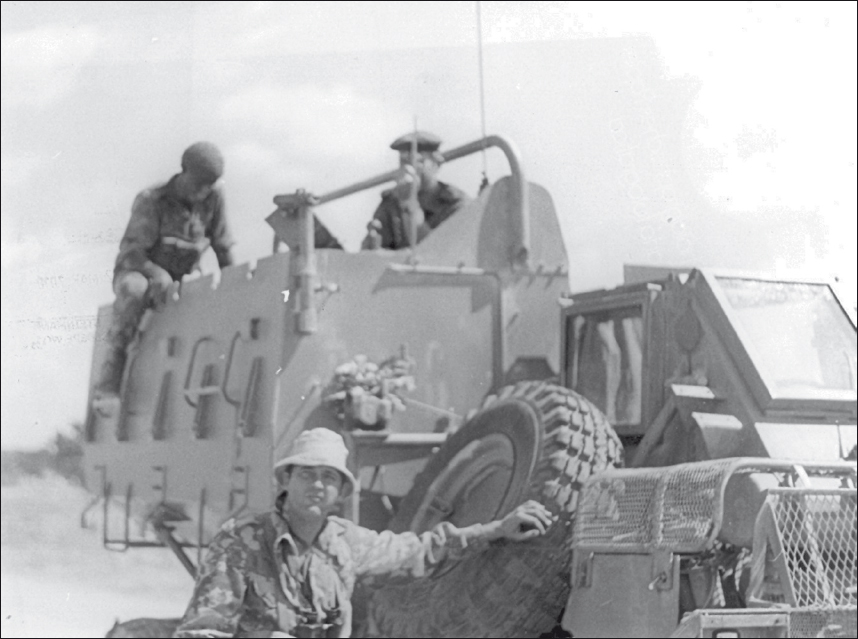

Final briefing: Cmdt Ferreira (seated right) briefing company and platoon commanders with faces already painted with ‘black-is-beautiful’. Kwevoël and Buffel troop transports are in the background.

They all wore our external ops cammo uniforms and the Portuguese-style army caps along with the distinct 32 Battalion brown leather boots with canvas sides and flat rubber soles. To this was added their first-line kit with its chest webbing, basic medical kit and hand-grenade pouches. They carried an assortment of weapons including AK-47s and R1s with the odd pistol as backup; light machine-guns such as Russian RPKs, RPDs and PKMs were carried along with FN NATO MAGs, the glistening 7.62mm ammunition belts draped over their shoulders. Support weapons included 60mm commando mortar pipes, ubiquitous Russian RPG rocket launchers with spare rockets tied untidily across their shoulders and the odd Snot-neuse (Afrikaans for snot-nose), a robust and dependable American grenade launcher. Bayonets were affixed to their web belts and extra grenades (fragmentation and phosphorous) were carried where there was space. Most troops had 60mm mortar bombs hanging off their webbing ready to pass along to the mortar guys when the fight started.

The officers and NCOs had VHF radios attached to their web belts, as part of their first-line kit, with the telltale blade antenna sticking up behind their armpits. They usually folded these in half with some black tape so they wouldn’t rattle or stick up conspicuously high. I could see the practicality behind this, but it certainly gave me grey hairs as it significantly affected the radio’s transmission range. No comms or bad comms was my responsibility, even given these idiosyncrasies. They were behind schedule and we still had a way to go. Watching this lot file past, I could understand why the Angolan Army referred to us as ‘Os Terreveis’ … ‘The Terrible Ones’ … we certainly looked the part.

What also stuck in my mind was the quiet, steady, assurance of the way they moved, even now that things weren’t going as expected. Having planned to attack at dawn, we were well behind schedule and we knew that we were up against greater odds than initially anticipated. Willem Ratte and his team had lost a valuable day for reconnaissance as they had been dropped off in the wrong position. As such, they hadn’t had time to carry out the detailed observation of the enemy base they had planned. After his initial reports of more activity in the base than that of the number of enemy troops estimated, Willem confirmed that there was significant activity on both sides of the airfield, with a notable number of enemy on the northern side of the airfield … against which we were sending only two platoons of Sam Heap’s Charlie Company. The other two companies, Alpha and Foxtrot, led by Jim Ross and Charl Muller, attacking from the south ahead of us in the HQ, had a wider area to cover. Even given Willem’s report of the greater than expected movement on the northern side, Ferreira could not be sure as to whether this was routine base activity or whether there were actually more troops present than anticipated. Hence, and as a result, he kept the plan unchanged.

Normal South African army attacks had all the conventional support of pre-emptive heavy artillery bombardments and air strikes, with the troops assaulting the enemy positions in armoured vehicles. We had none of that. This was to be the simplest and most basic of infantry attacks. Supported by a brief 81mm mortar bombardment that would only be effective if it caught the enemy out of their trenches, our troops would then attack the entrenched positions head-on with each soldier three metres apart and line abreast … the way UNITA guerrillas would do it. No surprise there, as it was UNITA who we were supposed to be emulating. Ferreira’s supreme confidence in his troops had him flout the basic military principle of only attacking if you outnumbered the enemy 3:1. We were not even 1:1 as there were only 350 of us against an initial combat estimate of some 400 enemy. And we now knew we were up against considerably more than that, and we were about to attack in broad daylight. Completely outnumbered and against the odds, we were committed to the assault. Commandant Ferreira was with us, not sitting safely back in a Tactical HQ somewhere. We trusted his judgement and leadership explicitly. There was a steady, measured confidence that settled amongst us. There was absolutely no doubt, no hesitation in any of our minds, about the task ahead.

Not long after the sun had risen, Sam Heap confirmed that Charlie Company was in position to the north. But the 81mm mortar guys were seriously behind schedule, having been hampered by even thicker bush down by the river where they had struggled to get into position. To this was added the heavy mortar tubes, base plates and all the big 81 mm mortar bombs they were burdened with. They also had great difficulty trying to communicate through the dense bush on their short-range VHF radio sets. Sergeant Piet van Eeden and the UNITA guide from Willem Ratte’s recce team were waiting to guide them in to their position – yet couldn’t get comms with them. As dawn approached, the two of them had to withdraw sharply to their Observation Post across the river. This left the mortar guys to find their own firing point, after which they still had to set up their base plates and tubes before commencing their fire mission. Whilst we waited, the sun continued to rise.

A message came through to us that there were three young boys walking up the road towards us. Ferreira’s orders were to bayonet them should they try to run back, but leave them should they continue to walk away from the FAPLA base. I sat there with my heart in my mouth, quietly willing them not to turn around. As they drew level to where we were sitting, one of them looked over to his right and suddenly saw me sitting there, deathly still and just a few metres away in the tall grass. As our eyes met, he visibly caught his breath and his eyes flew wide open, absolute terror etched across his face. I must have looked like the devil incarnate; armed to the teeth and dressed in my filthy camouflaged uniform, adorned with ‘black-is-beautiful’ camouflage paint streaking from the sweat on my face. Mesmerised, they stiffly kept on walking … away from the base. Once past us, they could contain themselves no longer and broke into a chaotic sprint down the sandy road, elbows pumping wildly and the pink under-soles of their bare feet flashing up nearly as high as their shoulder blades … boy, could those little fuckers run!!

It was only at about ten o’clock that our mortars finally swung into action. We heard the low, muffled cough of the bombs leaving the tubes off to our right, followed by the “ka-boom … ka-boom” as they began landing in the base ahead of us. The waiting was finally over … this was it. We followed the thin line of Alpha Company’s troops stretched out to our left and right, a couple of hundred metres ahead of us – with Foxtrot off to our right – advancing towards the sound of the crashing mortars. The base was so spread out that I couldn’t be sure what effect the mortars had, other than to chase the enemy into their trenches. Looking to either side of me I could see the black, battle-hardened troops from Lieutenant Trompie’s platoon assigned to us as ‘HQ protection’. They were walking steadily forward, three metres apart and line abreast. There were no other troops in the world I would rather have had at my side. The HQ moved forward in a loose group formation, Commandant Ferreira, Captain Erasmus, Sergeant-Major Ueckerman, myself, ‘Lappies’ the Ops Clerk and my signaller, Bruce Anders.

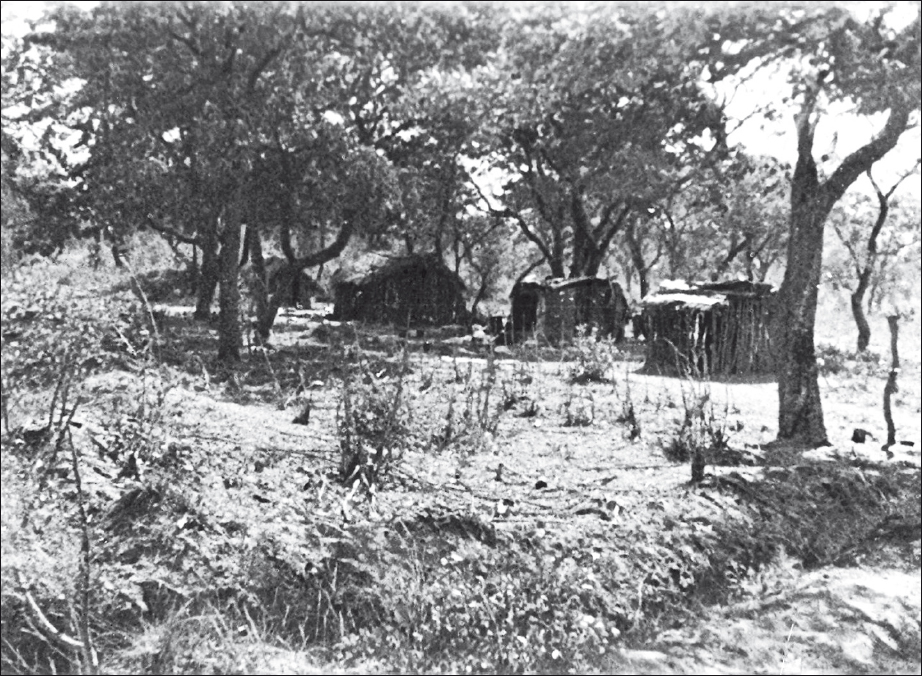

Part of the bunker system.

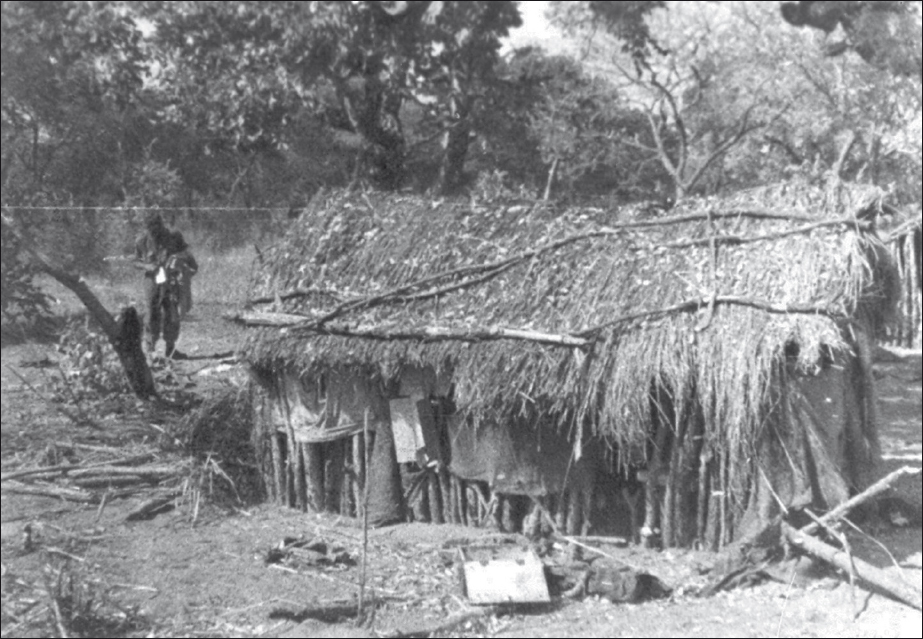

Sleeping quarters.

Temporary sleeping quarters to keep the sun and morning dew off.

The route followed by the HQ element from the beginning of the attack to the mid-afternoon mortar attack.

The terrain was very open, with scraggly three metre high trees scattered amongst the odd tuft of grass. The ubiquitous white sand kept tugging at the heels of my boots as I shuffled forward under the weight of the dreaded Machilla. The terrain rose gently ahead of us, before gently sloping down to the airfield that lay about 2km ahead. With the airfield just ahead in the middle of the base somewhere, Alpha Company were directly to our front, Foxtrot Company just off to our right, the river about 3km further on, whilst the mortar platoon was about 3km to our right and slightly behind us. The medevac post was to our rear and the logistics guys were just a little further back with all the vehicles and supplies.

A few minutes later an almighty roar erupted ahead of us as the companies came up against the trenches. We soon began hearing the angry buzz of rifle bullets as they neared the end of their trajectory, zipping viciously between us and someone decided that it would be sensible to take cover by lying flat on the sand. I lay there, already exhausted from almost no sleep the night before and from carrying the dreaded Machilla, wondering how I would ever explain the sound ahead of me. Nearly two thousand automatic rifles and machine guns were firing together, punctuated by the boom of exploding mortar bombs and RPG rockets, all of which filled the air around us whilst hammering our eardrums, numbing our brains and seemingly drilling down into our chests. The best analogy I can think of was that the gunfire sounded as if we were in a confined space with countless marbles beating furiously and continuously against a tin roof above our heads … a hailstorm gone mad. The ferociousness of the enemy’s response immediately struck a chord in us all … while we had always known that we would be outnumbered, the full extent of by how much began to dawn on us. However, there was nothing to be done, no alternative, but to follow through what we had begun.

Not long after the attack commenced, the whole sky from horizon to horizon suddenly filled with the roar of what seemed to be swarms of fighter jets shrieking over our heads. This was followed by a tremendous explosion a few kilometres behind us with a sound that rattled our teeth. One of the older hands muttered Monakashita (‘Stalin organs’ or ‘Red-eye rockets’) … it certainly frightened the living daylights out of us even though it went well over our heads. It must have scared the shit out of the mortar guys in whose vicinity the rockets were exploding. Not being very accurate and firing only a single rocket at a time, they did not have much success except for having a dramatic psychological effect. At this point someone wisely realised that lying prone wasn’t achieving much and the order to advance was given again. I struggled up off the sand and laboured forward under the accursed and heavy rucksack.

One of the many enemy dead.

Some of the huts in the base with trenches in the foreground.

No sooner had we begun to make our advance on the base again, when I heard the unmistakeably rapid beat of rotor blades and the whining turbines of a large helicopter approaching low, hard and fast … my blood froze. “Hind gunship!” someone called out and we scurried for suitable cover, but there was none. I feared these deadly helicopters more than anything, having heard a story of how one such aircraft had reportedly decimated a platoon of ours soon after the ‘75 Angolan war of independence. Its armour protection and chin-mounted cannon linked to the pilot’s helmet sight made it a deadly machine. Darting from pathetic tree to pathetic tree for cover, we must have looked like rats caught in a barn when the lights are suddenly switched on. The helicopter roared over us at tree top height and it was with huge relief that we saw it was one of our big Pumas. But what the hell was it doing here? We were hugely concerned as it had flown straight over the FAPLA army base and the raging battle ahead of us. It seemed the pilot had overshot the rear echelon group where he was to wait in order to casevac the wounded. He must have suddenly seen the airfield in the middle of the base, and realising where he was, turned the aircraft practically on the spot and shot out of there like a bat out of hell. A friend of mine, Lance Corporal Grant Larkin, who was an ops medic on board the helicopter, later told me that he was scared shitless they would take rounds up through the floor of the aircraft and he sat there helplessly praying one wouldn’t be for him!

The sound of the bullets had now changed to that distinct, deadly ‘whip-crack’ as they passed between us, and I knew we were now close. Unbeknown to us at the time, Alpha Company up ahead had advanced into a fire-storm, taking heavy casualties and they were soon to lose their Company Commander, Charl Muller and their Intelligence Officer, Tim Patrick … and we too were about to get drawn into the tail end of it. Trompie’s troops a few metres ahead of us started firing while moving steadily forward, but I couldn’t see anything. Astonished, I realised that the trenches were but five metres ahead. They were an ingenious design, a metre wide and deep enough for a man to stand in with his head and shoulders sticking out. They zigzagged off to our left and right, not running straight for more than three metres. What made them almost invisible, until you were on top of them, was that they had no protective mound in front of them, but rather were flush with the ground. As we were soon to learn, they were difficult to clear unless you systematically worked down the trench line. The companies ahead of us had advanced over the trenches to get into the base, as we were about to do. I peered into the three-metre section in front of me, and seeing nothing down there, backed up and took a running jump to clear it.

We hadn’t moved thirty metres into the base area when we started taking fire from behind us … the enemy were still in the trenches!! Everyone around me dived to the ground. With the weight of the Machilla on my back I was a lot slower, carefully kneeling to put my hand out in front of me and lower myself to the ground when I was suddenly pitched face forward into the sand. Thinking at the time it was the weight of the backpack, I later saw that a bullet had passed through the Machilla, missing my neck by a few centimetres. Being the only one carrying a rucksack that stood nearly as high as the top of my head, I must have stuck out like a sore thumb, making an obvious and inviting target. Trompie’s troops immediately engaged the enemy behind us. I rolled onto my side and pulled my arms free of the Machilla. I had had more than enough of carrying it, and I shouted to Bruce Anders to take over. He was clearly not happy at the prospect, but, fuck it, it was his turn anyway … and rank in this instance had its privileges!

Finally free of the burdensome pack, I was now ready to actively participate in the fight. I suddenly and inexplicably felt incredibly alive, aware of every sense in my body … as if on a high. I wasn’t tired any more, I felt fitter, stronger. I could see clearer with all colours being really vivid, my sense of touch was enhanced and my hearing sharper. I can only think that it must have been the adrenaline pumping through my veins that was channelling my fear into a positive survival mode, or maybe our training ensured this reaction and not the debilitating stomach-churning butterflies that was the alternative.

Seeing some huts off to our right, Captain Erasmus and I moved to clear them. I fired a few rounds through the wooden-poled wall of one hut while Erasmus did the same for another. Sticking my head through the door, I saw that it was empty. Erasmus screamed out “watch your back, watch your back!!” as we took fire from back up towards the trench line. I emptied my magazine in that direction, which only served to draw more fire. I changed magazines, pulling a fresh one from my chest webbing and throwing the empty down my shirt front. “Watch your back, watch your back!!” Erasmus screamed again as we took fire from the direction of the river. It suddenly dawned on me that he and I were alone, as the HQ group had moved on down towards the airstrip. I kept turning to face incoming rounds, not seeing clearly who was firing at us. Erasmus and I were spinning back-to-back, jabbering and shouting warnings to each other, moving in the direction we thought the HQ had gone. I couldn’t help thinking how comical it must have looked, two HQ officers clearly out of their depth, in the shit, in the midst of a raging firefight. The thought, “I can’t fucking believe I’ve got myself into this!” going round and round in my mind. From the huts to getting back to the HQ group is a blur… I simply can’t remember. How we found them I don’t know, and when we got there, I had two or three empty magazines clonking around in my shirtfront. I hadn’t had time to put them back into my chest webbing.

Enemy captured at Savate.

The OC had some sharp words to say to me about being separated from him as I was carrying one of the VHF radios he needed in order for him to access part of his command net. Little did he realise just how pleased I was to be back with the platoon and the extent to which he was speaking to the converted!

Trompie’s HQ defence platoon was strung out expectantly in a skirmish line running down the slope, facing towards the river. No sooner had we arrived when all hell broke loose around us. Unencumbered by the heavy Machilla, I dived with alacrity onto the sand. I fired off half a magazine between the two man MAG machine-gun crew a few metres to my left and Captain Erasmus in a clump of grass on my right, before crawling forward into the firing line. It was very comforting to hear the roar of the controlled bursts of machine-gun fire from the MAG to my left … and it was good to be back with the platoon. Running the risk of losing the initiative if we stayed stationary, I shouted through the maelstrom of gunfire to advance. The MAG gunners began gathering their glistening ammunition belts, draping them over their shoulders and preparing to hoist up the gun. Changing to my last magazine as I got up, I realised there was no response from Erasmus. “Captain, Captain … we have to advance, we have to advance” … no response again. Bruce Anders was shouting something behind me, and I realised he was telling me that there appeared to be something wrong with him.

Enemy captured at Savate.

I reversed back from the firing line, and crawled round alongside him in the grass. To my horror, I saw he had a hideous throat wound with blood gushing from his mouth as he struggled to breathe. Something snapped in me, and jumping up I ran down the skirmish line screaming for the medic. Thirty metres down the slope, I saw Sergeant Major Ueckerman on all fours crawling up towards me … an unusual posture for this big, burly Regimental Sergeant Major, with his red handle bar moustache and bellowing voice that struck the fear of God into all around him on the parade ground. He reached up and pulled me down by my chest webbing as I was about to run past him, still shouting for the medic.

“Looty, wats fout?” (Lieutenant, what’s wrong?)

Not making much sense at first, I took a deep breath and told him about Captain Erasmus and that he needed a medic, in fact, he needed a doctor, fast.

“The medics are all busy Looty, and so are all the doctors … there’s nothing we can do right now.”

“FUCK IT … … !” Numbly I began crawling back up to Erasmus. I looked behind my shoulder and to my amazement I saw Commandant Ferreira strolling up the firing line with his AK-47 slung casually by its strap off his shoulder. He had two VHF radios strapped to his web belt and he was listening intently, an ear-piece pressed to each ear. He was completely oblivious to the firefight raging round him, and while the rest of us were slithering around like lizards; he looked every bit as if he was out on a Sunday afternoon stroll. The advance had faltered on my side of the line when I had gone apeshit looking for a medic. I lay miserably in the grass next to Captain Erasmus as the fight continued. His left arm was thrust forward, twisted crookedly above the elbow. I watched helplessly as he slowly died, his gaping neck wound causing him to gulp for air as blood gushed from his mouth each time he tried to breath. Medically there was nothing I could do as this was way past my basic combat first aid skills. In fact I don’t think anyone could have done anything for him. His face slowly lowered towards the sand until his shoulders gently heaved for the last time. Helplessly, all I could do was stick with him and keep him covered, firing only when I had to, trying to conserve the last of my ammunition … it was possibly the longest, loneliest twenty minutes of my life.

The firefight slowly died down and I got up when I saw the OC standing behind me, still talking intently on his radio command network. Hoisting the Machilla up against a tree, I plugged a whip antenna into the big HF radio and switched it on in case the OC needed it. When I tried testing comms, I got a strange “bbbrrrrr” in the earpiece. Lifting the HF radio up, I saw a bullet hole through it. Inspecting the rucksack, I could see the neat entry hole at the back and the jagged exit. I realised with a chill that had I not leaned forward to lie flat when the enemy opened fire from the trenches behind us at the beginning of the battle, the bullet would have hit me in the back of my neck.

I heard the OC mention my friend Tim Patrick a few times over the radio. When he finished, I asked him if Tim was OK. “He’s dead”, he said quietly. An empty, numb, cold feeling settled in me and I turned and punched the tree next to me, which turned out to be a dumb thing to do as the bark was rough. Fuck … my hand hurt! At least it gave me something else to think about for a while. He had been burnt to death by a phosphorous grenade.

By now it was just past midday, and the battle had begun to die down. Reports started coming in from the various companies. Alpha and Foxtrot had taken the base to the south of the airfield as well as the few buildings that made up the village at the southern end of the runway; Sam Heap’s Charlie Company, which had hit the base to the north of the airstrip, had retreated in the face of overwhelming firepower, most notably from a 14.5mm antiaircraft gun. They had come back round to our side of the base. And then my friend Heinz Muller’s name came in as one of those killed. He had taken three machine gun bullets to his stomach, and died an hour later … . I sat down next to the Machilla with my back against the tree, rifle across my lap with that empty cold feeling settling in my stomach again. I looked numbly up into the beautiful blue of the sky and took a deep breath … “Justin, jy moet lekker wees” (“Justin, you must go well”) echoed in my mind. Now it made sense. He had been saying goodbye and had been wishing me well. “FUCK IT! … . FUCK IT!” I said quietly as my emotions welled up. A deep sense of helplessness threatened to overwhelm me.

We began gathering ourselves together to regroup on the side of the base closest to the river. Bruce Anders suggested it was now time to abandon the heavy Machilla, with the now unserviceable HF radio, which had proved such a burden during the battle. When we had come under fire just before Captain Erasmus was shot and he had dived for cover, the heavy rucksack had pinned him face down. So much so that he couldn’t even lift his head. In his attempts to extricate himself, it caused him to roll onto his side, almost like a tortoise on its back with its legs flailing in the air. As he struggled to free his arms from the straps with bullets cracking past his ears, he was convinced they were to be his last moments. I could understand his aversion to the rucksack but I insisted he pick it up. He later told me the only reason he did what he was told to do was that, from the look in my eyes, he was convinced I was going to shoot him on the spot for insubordination!

As we were about to move off to regroup, I noticed a young FAPLA soldier who had been brought in by the troops. Lying propped up on one elbow, he looked up at us with a beautiful trusting smile, flashing white teeth against his boyish black face. His foot had been shot off just above his boot, and it was hanging loosely by some skin. Surprisingly, there was very little blood. I remember feeling unreasonably pissed off with him and at first, thinking “you might have no foot but at least you are alive you miserable fuck”.

“What do we do with this guy?” I asked, as we were about to move off …“Shoot him” came the reply. “Jesus Christ!!” I muttered quietly to myself. Stunned at this directive, I saw he was still smiling anxiously and his eyes were darting furtively between us, not understanding what we were saying, confused as to who we were and desperately seeking empathy. Shoot him? I couldn’t do it. I turned to Lappies who stood next to me. Seeing the look in my eyes and before I could say anything, he exploded “Nee vok!” (“No fuck!”)… his contemptuous attitude for once working in his favour. I then noticed one of our black troops step forward and, miserably, I turned my back and began to walk away.

Following the OC and his group, I turned to see the troop dispatch the wounded FAPLA soldier. Being a battle-hardened veteran, I was surprised to see how he had to brace himself. Standing over him he placed his legs apart and with his rifle pulled firmly into his shoulder, he fired three rounds into him. I guess the young FAPLA troop had got up too close to us and the risk of him surviving, to tell the tale of strange white men with blacked-out faces, was just too great. Being in the middle of the battle we couldn’t get him back to any medical assistance anyhow. His youthful face, with the beautiful trusting smile, desperately seeking empathy from us, haunts me to this day.

Walking towards the river and the reorganisation area I saw a small tongue of flame licking at a patch of grass, and wondered if that was where Tim Patrick had died. A little further on we came across the massive mobile pontoon bridge which finally explained the tank tracks we had seen in the aerial photos, and which had caused such consternation and debate in the planning phase … tanks … the mere thought of them had struck the fear of God in me! If I had come up against one, my plan was simply to run like hell! They were parked in an area that appeared to be a field workshop as there were some vehicles scattered around in various states of repair. One of the platoon commanders later showed me the mark on the top of his cap, which had been shot off his head by a FAPLA soldier hiding behind one of these vehicles. He had then managed to kill him, shooting him in the head as he peered round a wheel … it had been a close call! We moved on past one of our massive Kwevoël lorries parked under some protective trees. It had an armoured cab and a large flatbed at the back. They were loading our dead onto it and the body bags pretty much covered the entire flatbed.

Soviet mobile pontoon bridge.

We came to the high ground that looked down onto the floodplains leading to the river and met up with a handful of Buffels that had come down to resupply us. I thankfully reloaded my magazines with fresh rounds. We were straddling a small two-track road that ran down into the tiny village that was between the airfield and the river, and through which the main north-south road ran. There was a steep bank between us and the main road.

I was between the Buffels and the bank when a black troop asked me what to do with a FAPLA soldier he had with him. He was a well-built, fatherly looking guy with a horrendous wound on the side of his neck. It had splayed open revealing raw, matted flesh. I did a double take as I had assumed he was one of ours. Both Three-Two and FAPLA were wearing camouflage battle fatigues that looked very similar – it was difficult to tell the difference until you got close up, and it was this that had caused so much confusion in the early parts of the battle. Before I could answer him, and right on cue, a mortar bomb crashed down a few metres away. The troop dived for cover and I instinctively ducked. I turned to see the FAPLA soldier making good his escape and was bringing my rifle up to bear when another mortar bomb landed about 30 metres away. Self-preservation taking priority, I turned and instinctively ran for the Buffels. I last saw the prisoner disappearing down the bank towards the river.

The mortar bombs began to crash down amongst us in earnest. The Buffel drivers had decided that discretion was the better part of valour and were returning to the holding area behind us with a great deal of alacrity. I was running towards them in a half crouch, flinching with each explosion, undecided and unsure as to what was going on as the Buffels bucked and roared back up the track. As if in slow motion, I saw one of the drivers through the armoured glass panel on either side of his head. As he drew level with me a mortar bomb exploded just the other side of the Buffel. The armoured glass on the far side of his head starred instantly into a myriad of spider webs as shrapnel smashed into it. Spurred on anew, with the big diesel bellowing, he careened off up the sand track with the armoured vehicle swaying and bouncing around like a bull gone mad.

With nowhere to run to, I turned and headed back to where I had started and saw the OC walking towards me. I dived onto the sand and crawled into a small indent under a scraggly bush, thrusting my rifle foreword. Not being able to see anyone else around, the OC joined me to peer through our meagre cover, not sure what to expect. Were the enemy just trying to hammer us or was this the precursor to an infantry counter-attack? Some of the bombs were hitting the branches of the trees above and shrapnel whizzed menacingly down into the sand around us. The mortar barrage was reaching its crescendo when one exploded just a few metres in front of us and chunks of shrapnel smashed through the bush, just inches above our heads. The OC wriggled closer, trying to share my measly indent for cover. I moved half out to make room, not that it gave us much protection. It was the first time I had seen him show any concern for his own safety.

He immediately started speaking on his command net again. I heard the mortar platoon commander ask if he should use the new phosphorous mortar bombs in retaliation. Fresh from the research factory back in South Africa, it was the first time we had taken them into combat. Being the humane person he was, he was reluctant to use these as they would inflict terrible wounds. On impacting the ground, these bombs would explode and disperse a cloud of deadly phosphorous to a radius of about thirty metres. Phosphorous burns when exposed to oxygen, making it almost impossible to extinguish if it lands on you. He hesitated and seemed to reflect on the day’s events, before steeling himself and giving the command to open fire with them.

With the mortar duel gaining tempo, Commandant Ferreira and I lay beneath our pathetic cover. I had my left forearm out in front of me with my rifle resting on it to keep it out of the sand. Mortar bombs continued to crash around us and with not much else to do but wait for whatever, I rested my cheek against the stock of my rifle and fell into an exhausted sleep. I woke up hearing “Justin! Justin!” as Ferreira elbowed me urgently. When he saw that I was merely asleep and not dead, he said with relief and humour in his eyes “It’s a terrible war, isn’t it!?” I grunted a reply and fell asleep again with the mortars still smashing down, seeking us out amongst the trees.

Unbeknown to us, Ferreira and I were almost alone. The Buffels had all dashed back out of range of the mortars and most of Alpha and Foxtrot companies’ troops had melted back towards the rear echelon vehicles, to escape the mortar bombardment. Having survived the madness of the earlier assault, they had had enough. On getting to the vehicles, they were ordered by Sam Heap to return immediately. Most of them had little or no ammunition, yet they turned and followed their leaders with no hesitation at all, back to where we were lying under our bush. Had the enemy counter-attacked, it would have been just the OC and I with a few isolated pockets of our troops scattered around. Added to which if I was to have been any use, Ferreira would have had to wake me up!

I woke up again a little later with Corporal Peter Lipman calling urgently over the radio, wanting to know what to do … he reported between thirty and forty enemy advancing towards their position against the river, north of the base. There were only three of them in his position. He was part of our group of thirty reconnaissance men deployed in sticks of three, to the north of the FAPLA base. I relayed the message to the OC. He thought for a moment, then said “Tell him he was put there as a stopper group, he must do what he was put there to do”. I paused, and took a deep breath before relaying the instruction to my friend… feeling every bit as if I was sentencing him to death. It was a sentiment he seemed to share as it was with a tone of disbelief that he acknowledged. And so the three of them stood their ground and opened up on the mass of enemy troops.

He later told me that when they opened fire as ordered he had tears streaming down his face. I have always judged bravery by the extent someone is prepared to acknowledge and express fear, and it’s the manner in which they control that fear that determines their courage. Pieter Lipman is a brave man. His machine-gunner, Rifleman Alberto, was soon shot in the stomach, putting him out of action. He died before we could casevac later that afternoon. Now down to just himself and Sergeant Kevin Fitzgerald they were hopelessly outnumbered, but they desperately continued to pour fire into the enemy as they advanced towards their position. They were only saved from being overrun by two of the other three-man sticks led by Sergeants Gavin Monn and Gavin Veenstra. They ran down to their aid, hitting the enemy on their flank, firing their automatic rifles along with some shoulder-fired disposable rocket launchers. The latter gave the enemy the impression there were more of them than there actually were. Those not killed soon scattered and ran for it.

Not knowing how Peter Lipman and the stopper groups were doing, I feared the worst as what was left of the FAPLA Brigade was streaming north, straight through their positions. Incredibly there were only thirty of them in scattered stopper groups sited against literally hundreds of the fleeing enemy. Of one thing I was certain and that was that they certainly had one hell of a fight on their hands. However, my fears as to their fate were to prove unfounded as they wreaked havoc amongst the enemy, with Rifleman Alberto being their only casualty. The fact that they were in small teams must have given them the advantage of mobility and this, combined with their aggressiveness, enabled them to account for scores of enemy dead.

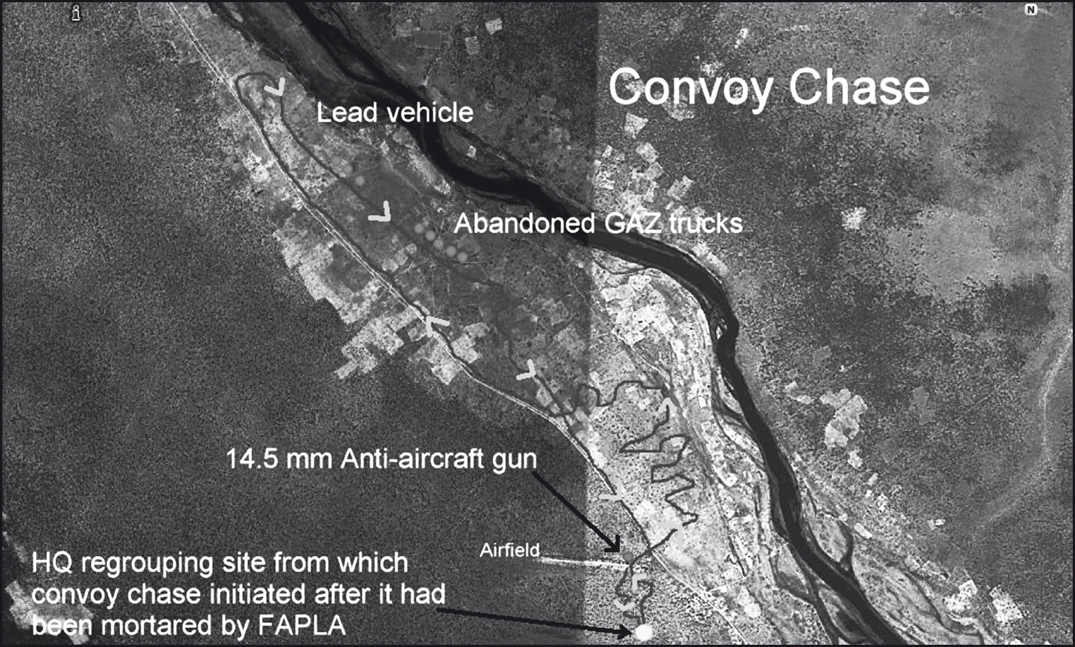

The convoy chase in the late afternoon by the three Buffels.

I then started hearing reports that the enemy were attempting to break out to the north in a convoy, reportedly some twenty to thirty trucks with between two and three hundred troops. The convoy was avoiding the road (they had correctly guessed we had mined it) and was heading up between the road and the river. I soon heard the OCs conversation over the command net mentioning Charl Muller’s name and that he might be a prisoner with the FAPLA column. He had been missing since soon after the battle began, and had last been seen bandaging his hand. We were also missing Corporal Engelbrecht and his radio operator from one of the companies. Should they be in that convoy it spelt disaster. It would have blown the lid off the clandestine nature of the operation, allowing the Angolan government to display them in Luanda for the entire world to see. Given this potential calamity, Falcon decided to throw caution to the wind, and instructed the Alouette gunship to attack the convoy. This wasn’t without considerable discussion with the Air Force guys behind us. His hesitation before committing the gunship was due to the fact that it would compromise the covert aspects of our mission as UNITA did not have such gunships – only the South African Defence Force had helicopter gunships in that theatre of war.

The gunship had been sitting a few kilometres back with the rear logistics group. We soon heard the clatter of its blades and whine of the turbine as it roared over us, its single 20mm cannon sticking out the side. The pilot soon reported the convoy in sight in a calm, cool voice with the unmistakable throat rattle caused by the vibrations of a helicopter.

The engineer-gunner opened up with his cannon, firing three rounds at a time with the explosive heads hitting their targets a few seconds later. Any more than that and the chopper would be thrown out of control.

“Ba, ba, ba … … do, do, do” … … “Ba, ba, ba … … do, do, do”. He hadn’t fired more than a few bursts when all hell broke loose as everyone in the convoy opened up on him with automatic rifles. This was punctuated by the boom of RPG-7 anti-tank rockets, which having been fired at the chopper, would self-destruct when they failed to find their target. This went on for a considerable time and given the odds stacked against him, there came the inevitable. “We’re taking rounds, we’re taking rounds … … we’re hit … . disengaging, disengaging!” It was the only time I heard one of those pilots on the radio sounding not so cool! The fact that our lone gunship had attacked the entire convoy single-handed was crazy anyway. He came roaring back over us, skimming over the trees at one hell-of-a speed, desperately trying to get back to the rear echelon before he fell out of the sky. I could just imagine him thumping his helicopter down in a cloud of dust and then he and the engineer-gunner running like hell, their green flying overalls flapping, in case the chopper exploded.

With that not having gone too well, the OC instructed me to request as many Buffels as possible to be sent forward. They would form a flying column that would attack the fleeing convoy. Only three Buffels arrived, one of which was our command vehicle stacked with all my Tac HQ radios. Undaunted, the OC scurried around with a spring in his step, rallying troops to volunteer for his sortie. I was making myself look as inconspicuous as possible when he spotted me loitering off to the side. “Justin! Get into your Buffel … you are coming too!” My heart sank. The OC had to be fucking crazy. Three Buffels against the entire convoy, some thirty vehicles and three hundred troops! It was with a feeling of absolute dread that I climbed up the side of the armoured vehicle. I passed my personal Machilla rucksack to one of the guys staying behind, telling him what to do with the contents should I not return. I reminded him about the St. Christopher I had in my pocket from my girlfriend and asked him to make sure it got back to her. I was convinced we were on a suicide mission.

UNITA guide (barefoot with machete) and, possibly, Commandant Deon Ferreira, inspecting the base the day after the attack.

There was great activity and scurrying around as we prepared ourselves, checking ammunition and weapons. From my perch up in the Buffel I noticed Corporal van Dyk emerge from the bush and called out to him. He didn’t hear me in the commotion, which was a good thing. Had we made eye contact I fear the raw emotions of the day’s events may well have caught up with me. As it was, I had a lump in my throat as I watched him hurry past, looking a bit dazed and with a thousand yard stare in his eyes. He had been with Sam Heap’s Charlie Company which had taken a hammering to the north of the base … so much so that they had had to retreat back to our side of the airstrip. In addition, John had worked together with Captain Erasmus and Tim Patrick in the intelligence section back in the HQ … both now dead.

The Buffel’s big diesels roared to life and we headed down the track towards the village. There were only about seven of us in our Buffel. The OC was sitting next to me on my right, just behind the driver so that he could shout instructions at him. The RSM sat behind us with Bruce Anders beside him. Staff-Sergeant Ron Gregory manned the Browning machine-gun mounted at the front of the Buffel. A professional soldier, he was an elderly Englishman with a wide scar on the side of his face. Some time back, an RPG anti-tank rocket had exploded in a tree next to his head. He walked and talked very deliberately as a result and was very hard of hearing. The Buffel in front of us only had about four guys in it, the machine gunner, Lieutenant Jim Ross with a 60mm mortar pipe and two others. Looking behind us at the other, I saw there were only about eight guys with Sam Heap in that vehicle. Each could have carried ten. With so few of us going up against the whole convoy, the feeling of impending doom settled even more firmly about me.

We came out of the trees and into the little ‘village’ of roughly five buildings that straddled the main north-south road. There were about a dozen bodies lying scattered on the ground with a few civvies wandering aimlessly around. As we roared through, I suddenly realised that the road ran up and over the end of the runway. With dread I remembered the reports coming in during the battle of one of our platoons being pinned down by a 14.5mm anti-aircraft gun that was on the end of the runway at the other side. Its huge rounds would cut through our lightly armoured Buffels from end-to-end like a hot knife through butter. Numbly I watched the Buffel ahead as it approached the runway, waiting for it to get cut to shreds, before the gun was then turned on us. To keep my mind off the reality, the Beatles lyrics “Picture yourself in a boat on a river, tangerine trees and marmalade skies … somebody calls you, you answer quite slowly … Lucy in the sky with diamonds … .” kept spinning over and over in my mind. Suddenly we were up on the runway and from this elevated perch I could see the smoke drifting lazily up from where the phosphorous mortar bombs had exploded earlier, off to our left and ahead. To our right, the lead Buffel had already made it into the grass, heading off between the main road on the left and the river on the right. The tail end of the convoy was about a kilometre away on the open savannah. As we came down off the end of the runway, I saw the barrel of the deadly anti-aircraft gun pointing idly up into the sky off to our left … luckily it had been abandoned.

Dismantling one of the dreaded 14.5mm anti-aircraft guns.

In a flash we were over and off the end of the runway, barrelling down into the grass and low scrub, accelerating towards the convoy. The five-ton Buffel was going at speed across the open flood plain, bouncing and swaying crazily. The 7.62mm Browning in the Buffel ahead of us opened up and Jim Ross started firing a hand-held mortar pipe. How he managed to get each bomb to go towards the convoy and not straight up and back down on us I will never know. Holding the base of the mortar tube on the rubber seats of the bouncing Buffel, Jim’s number two would drop the bomb down the pipe. With each detonation, the mortar pipe would bounce crazily up off the rubber seat, jumping almost above Jim’s head. The pair of them were like kids, laughing each time Jim tried to control the bounce of the mortar pipe. The Buffels fanned out and all the Brownings were now firing with their characteristic stutter, tracer bullets flicking out towards the convoy … and then, of course, ours jammed! The expletives flew at poor old Ron Gregory as he struggled to clear the gun whilst being smashed around by the careening Buffel. He would manage to clear it, fire a short burst and then it would jam again. He gave up trying after a while and grabbed his rifle instead.

Having taken one look at the three Buffels charging wildly toward them, the FAPLA troops broke amongst their vehicles and ran in every direction. I also think that the mortar rounds fired by Jim Ross gave them the impression that we had a lot more firepower than we actually had. Had they stood their ground and taken us on with a few well-aimed RPG-7 rockets we would have been in serious trouble. Any semblance of co-ordination between the Buffels soon fell apart as we each chased after a batch of the fleeing enemy.

A captured truck loaded with supplies. Nearly 500 weapons and 150,000 rounds of ammunition were recovered.

Initially firing my rifle on semi-auto, I soon flicked to automatic fire. I had stuffed a whole case of ammunition under my seat, so with an ‘unlimited’ supply of rounds, I could throw caution to the wind, simply dropping my empty magazines onto the floor of the vehicle instead of having to stuff them down the front of my shirt. By this time the FAPLA troops were obviously tiring as they merely jogged along, even when my rounds found their mark and one of them would be bundled into the grass. The automatic fire thing didn’t last long as I soon found that I had better control of my weapon on semi-auto, rapidly placing each shot. I can remember thinking “Now THIS is how you fight a war”, comfortably sitting in an armoured vehicle with all the ammo I needed at my feet.

We soon ran out of targets and found ourselves alone, making heavy going of it in some bushes. Ferreira decided to make for the road and cut off the convoy by coming down at them from the front. He was in constant communication with Major Eddie Viljoen (Echo Victor) who was in a Bosbok spotter plane above us. He would tell us when to turn off the road. It was about this time that I overheard Echo Victor laughing over the VHF radio in such a manner that it sent a chill down my spine… the FAPLA troops trying to swim across the Kavango river to escape us were getting taken by crocodiles … and he thought this was a huge joke!

The Kavango river that runs past Savate with an Angolan army truck that didn’t make it across.

We were soon accelerating gloriously up the big dirt road, revelling in the speed and the smooth ride. It suddenly dawned on me that our recce troops had mined the road leading north of the base and I reminded the OC of this. He didn’t answer, just kept glancing up the road and wriggling in his seat; he was waiting for Echo Victor. “Fuck, all I need is to get blown to smithereens by one of our own mines” I thought miserably. I tightened the harness holding me into my seat and hoped for the best. Finally the call from Echo Victor came and we cut off the road into the bush, heading for the river. We came up against a seemingly impenetrable line of bushes as high as the Buffel. Echo Victor told us that what was left of the convoy was on the other side and to our right. We paused, not sure. My suggestion was to send someone on foot to check it out, lest we get taken out by an RPG as we burst through into who knew what on the other side. In addition, we couldn’t be sure the line of bushes didn’t conceal a bank, over which we could somersault, spilling out of the overturned Buffel in full view of the enemy … my imagination was running wild … and I was starting to lose my nerve.

The OC looked at me, then at the bushes, then back at me before deciding not to heed my advice and ordered the driver to smash through the bushes. His gamble paid off, no bank and no RPGs. Sure enough, the lead vehicle was barely eighty metres off to our right. As we charged towards it, I stood up and turned to fire over our driver’s head, twisting my rifle so that the ejecting cartridges would spin up and not into the OCs face. I heard my first round hit the windscreen with a distinct crack, and the door flew open as the driver jumped out. I saw these white tekkies (tennis shoes) appear on the step of the cab, looking very out of place below a camouflaged uniform, before he fell out onto the ground. I fired two or three more rounds into him and he lay crumpled in a heap. I looked across at Sergeant-Major Ueckerman and saw that he had also pumped a few shots into him … he hadn’t stood a chance. Almost in slow motion, with its driver’s door hanging open, the truck continued forward, rolling down into a ravine and smashing into the opposite bank.

Our Buffel charged on, towards a batch of about five abandoned trucks parked one behind each other. The guys sitting behind us were firing at something when I heard a loud bang. A bit dazed, and feeling something warm and wet I looked down to see blood flowing from the back of my hand. “Commandant, I’ve been hit” I said to the OC sitting next to me. He was talking to Echo Victor over the radio and without a pause he said “Justin’s hit, Justin’s hit” and went right on with what he had been saying before. I felt no pain in my hand and so started checking the rest of my body, to find that I had been hit in my upper arm as well. It must have been fragments of a bullet that had disintegrated against the inside of the Buffel, spraying my arm like a shotgun. For a few years after that, I occasionally had small dark metal fragments work their way up and out of my arm. For the moment, we bandaged my arm and hand as best we could to stop the bleeding.

One of our Kwevoëls towing a captured vehicle.

We circled the abandoned vehicles and then headed back as it was now getting late and we didn’t have long before the sun set. We passed the body of the driver and with my emotions welling up I said bitterly, “Commandant … I shot that fucking cunt for Tim”. I had never used language like that in front of the OC and no sooner had I said it, than I realised what a stupid thing it was to say. He didn’t reply but looked off into the middle distance. It had been a long day, and I suppose there was nothing more to be said.

By the time we got back to the southern part of the Savate base it was dark, and our driver got lost, driving slap-bang into a trench. As our Buffel crashed down into the other side of the trench, I saw sparks fly out of the engine. “Now we’re fucked” I thought, looking anxiously around in the gloom. Ferreira used some choice expletives to describe the driver’s parentage, his mother’s bad choice in bringing him into the world and leaving him in no doubt as to the only thing his sister would be good for if he had one! They got on well and had a healthy respect for each other, which makes it humorous looking back. The OC was getting jumpy, we were all jumpy – we had had enough. Our front wheels were suspended in the trench, spinning in the air, whilst the back wheels were still on the ground and our tail was sticking up. While we were radioing for the other Buffel to come and pull us out, the driver put our vehicle into low ratio, four-wheel-drive and simply reversed out. Incredible!

Eventually, we made it back up to the area we had started from, and laagered for the night a little further up from where we had been mortared that afternoon. I got Bruce Anders and Lappies, the Ops Clerk, to help me dig my slit trench just off the sandy two-track road, as with my left hand in bandages, I could only use one hand. I sat with my feet in the trench, and scratching a slit in the soft sand, I dropped an Esbit (small solid fuel cooker) into it and heated some bully beef. This was the first thing I had eaten all day. My ‘fire-bucket’ of sweet, hot tea was refreshing and comforting. I slid thankfully into my sleeping bag with my boots still on and my rifle alongside me. Looking up through the branches I saw the familiar stars, so clear and so close I could almost touch them. I fell instantly into a deep and exhausted sleep.

I was dragged up out of my numbing sleep at dawn by one of the CSI operatives. He was battling to get comms back to his HQ in Rundu, about 400km away. I hadn’t had a straight eight hours’ sleep for about two weeks, and groggily checked his HF radio, battery levels, frequency, antenna connections, antenna length to frequency (exact quarter wavelength) and got him good comms with his base. He stood off to one side, watching me with a quizzical look. He had flown in the afternoon before and was wearing his clean army ‘browns’ and with no ‘Black-is-beautiful’, had a pristine, clean-shaven white face. I was sitting in the sand, crouched over his radio automatically going through the motions that now came so readily, exhausted, rumpled, unshaven, wearing filthy camouflaged battle fatigues, my face covered in three day old ‘black-is-beautiful’, blotched and streaked with sweat, and my left arm wrapped in dirty bandages. No doubt I didn’t smell too good either, as he seemed to make a point of standing a good few metres away. Mumbling acknowledgement to his thanks, I picked up my rifle and went back to sit on the edge of my slit trench.

I made a fire-bucket of coffee and with my hands wrapped around the warmth of the drink, enjoyed the crisp morning with my elbows on my knees. Everything looked fresh in the cool air, and it was good to be alive. The previous day’s events hung heavily in the back of my mind. It was the start of a long process of sifting through conflicting emotions in order to come to terms with it all. We were sent back up to the convoy we had hit north of the base, spending the morning searching through the abandoned vehicles and blowing them up when we were done. There was a huge amount of kit on the back of the trucks and I scored an AK-47 bayonet off a pile on one of them, and two sets of Russian artillery binoculars from behind the seats of another. There must have been about forty sets there; a huge pity to see them go up in flames. We were searching around the head of the convoy when one of the guys scouting out ahead came up short with a grimace on his face. He had found the body of the driver the RSM and I had shot to pieces. For years after that I was to have a recurring nightmare … one where I would be walking through the grass and would come across the bleached bones of the driver sticking through what was left of his tattered uniform.

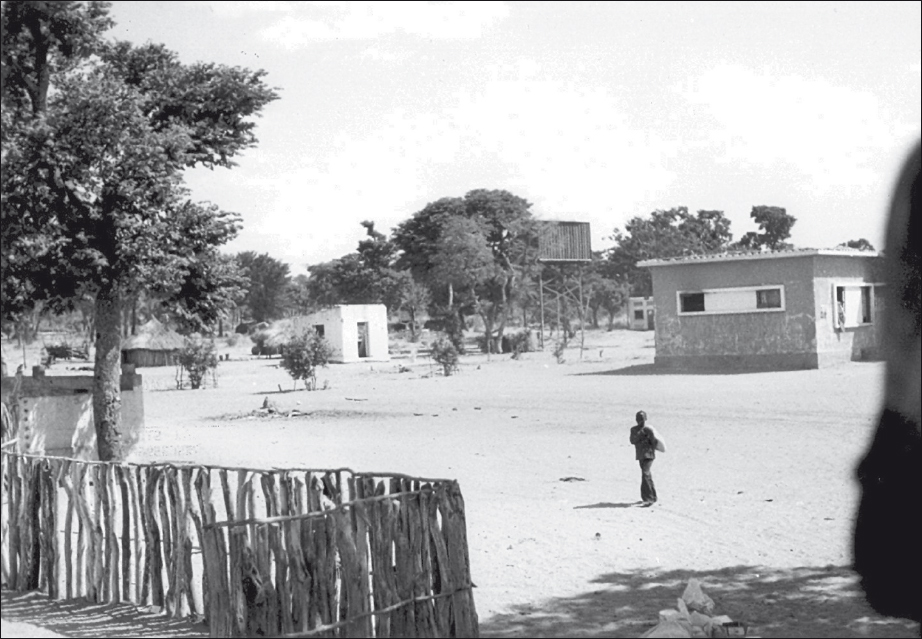

Savate village - the main street situated to the west of the airfield and straddling the main north-south road.

Our recce troops inspecting the vehicles in the convoy that was stopped heading north.

Cmdt Oelschig, Chief Staff Intelligence and Cmdt Deon Ferreira, Officer Commanding, 32 Battalion. (Courtesy of Piet Nortje)

We were at the tail end of the convoy when a shout went up. A FAPLA soldier was coming out of the reed bed next to the river, AK-47 in hand. From up in the Buffel, my R1 rifle came effortlessly into my shoulder. As I centred my sights on his chest, one of the intelligence guys shouted “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot, we need him as a prisoner”. Leaving nothing to chance, I kept my sights on him saying quietly to myself “run you motherfucker… run”, willing him to try and escape so that I could drop him. What the hell had come over me?!

Heading home on a captured vehicle.

Loading ‘Stalin Organ’ or ‘Monakashita’ rockets onto one of our Kwevoëls.

They disarmed him, pushing him up into the Buffel. He had a real attitude that earned him a good few ‘klaps’ around the head to remind him who was who. We took him back to the rear echelon area from where he was choppered out in one of the big Pumas, together with a handful of other prisoners, back to Rundu.

As it turned out, Charl Muller hadn’t been on the convoy as they had found his body late the previous afternoon. He had been shot at close range in the back of his head before being dumped into the bottom of a trench. However, Corporal Engelbrecht and his radio operator were still missing.

We went back down to the village to meet up with the OC. It was late in the morning now and we were parked just south of the village. The RSM had commandeered a really cool, open Toyota Land Cruiser that was parked nearby. He was waxing lyrical about how he was going to cruise around back in Rundu in his piece of war booty. I could just picture it, broad chest puffed out, big red handle-bar moustache ruffling in the wind with his camouflaged 32 Battalion beret at a rakish angle, when with an ear splitting ‘Cabooom’, the bonnet of his treasured Land Cruiser went sailing up into the air. “Wat die fok?” (“What the fuck?”) he shouted, his mouth falling open and speechless for once. Rick Lobb, from the recce teams, had fired an RPG-7 anti-tank rocket into the engine block to see what effect it would have!

The OC arrived soon after with Echo Victor and a CSI operative. While we were catching up relating the day’s events, the CSI guy moved off to take a photo of us (see next page). They were the only ones allowed cameras on such sensitive operations. I was resting my injured hand up on the spare wheel of the Buffel as it was bothering me and especially hurt when it was hanging free. My back is to the vehicle in the photo. I’m talking to Rick Lobb and someone else who has his back to the camera. Major Eddie Viljoen (Echo Victor) is on the left with Commandant Ferreira second from the left. Two whip antennas are visible from the radio sets I had built into the command Buffel. Ron Gregory had taken his errant Browning machine-gun off as can be seen by the empty mount on the top of the Buffel. True to the toughness of these vehicles, no damage is visible on the front of the vehicle from dropping into the trench the night before. This photo was kept along with others in a photo album in the intelligence room back at the HQ at Rundu. Of the other photos, one was of the mobile tank-tracked pontoon bridges that we had discovered in the base.

Left to right: Cmdt Deon Ferreira, Maj Schutte, Sgt-Maj Ueckerman, Capt Sam Heap (bandaged face), Cmdt Oelschig CSI, Capt Jim Ross.

Left to right: Major Eddie Viljoen, Cmdt Deon Ferreira, Cpl Rick Lobb, unknown (back to camera), 2Lt Justin Taylor, with bandaged hand up on the spare wheel.

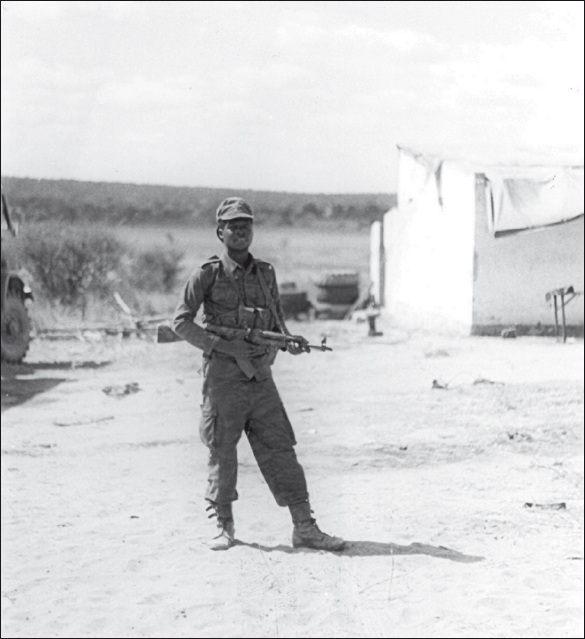

UNITA guide working with the CSI, standing with AK-47 in the town.