Home

The next day was a Sunday and some mates told me there was a Flossie filled with cargo returning to Pretoria that afternoon. Tim Patrick’s funeral was to be later in the week down in Natal and they could organise a jump seat for me if I could get out of hospital. I told them to go ahead and organise the seat as I would discharge myself then and there. I got up and was pulling the drip out of my arm when the medic came in and had a coronary! He told me I was supposed to stay till Wednesday and that I was not allowed to leave and threatened to call the doctor. The drip was out by then and I told him he may as well call the doctor as I had made my decision. After all, this was the medic who had nearly killed me the day before, so fuck him. He called the doctor but by the time he arrived I was already in my army browns with my boots on. When I explained that I had an opportunity to catch a lift on the Flossie that afternoon, to get back to my mate’s funeral, there was not much he could say. It wasn’t as if I was dying in his hospital anyway, it was just a small shrapnel wound. Whilst he wasn’t too happy, he sorted me a bag of pills and gave me the instructions that went with them.

My girlfriend was doing her nursing training at Greys Hospital in Pietermaritzburg at the time. She spotted me coming down the street, arm in a sling and dressed in my standard SA Army ‘browns’, my Three-Two boots and camouflaged beret – I thought I looked quite cool. In a scene straight out of a movie, she came running out in her white nursing uniform and squeaky brown shoes to throw her arms around me. The funeral was really awkward, as I couldn’t tell Tim Patrick’s family what happened, having to stick to the story that was in the newspapers. We had supposedly run into a massive ambush in South West Africa, resulting in the deaths of the white 32 Battalion guys. Our black KIA didn’t crack a mention as they were stateless, being neither South African nor Angolan citizens. Even Time magazine were duped, they reported the Battle of Savate as a significant UNITA victory.

The initial intrigue around the clandestine nature of the war we were fighting began to wear very thin. Dealing with the emotional issues while not being able to talk about them, turned out to be increasingly difficult. My university friends were living their student life … beer, cars and girls. While I could certainly see the attractions, I couldn’t relate to it. My worldly possessions were a rifle, my Machilla rucksack and what fitted in a balsak (kit bag). I needed money only to buy chocolate and a few beers when in base. Everything I did revolved around the singular issues of life and death and there were no grey areas in between. It was a very simple existence. I just couldn’t see the relevance of what they found important.

I had been given two weeks R & R and returned to the unit after only a week. I had been back at the HQ in Rundu for only a few weeks when it was tactfully suggested (in a way that I knew I didn’t have an option) that I should take my full annual fourteen days leave. I skipped my Varsity mates this time and went straight back to the family farm in Zululand. It was really awesome spending time at home with all that was familiar. When my mother asked me about the wound in my arm, she wanted to know if I had had to fire my machine-gun during the battle. “Something like that” I replied with a wry smile. My elder brother told me about the incident when a couple of days after Savate (about which he had no idea), the local Dominee (Afrikaans priest) had excitedly rushed onto the golf course to officially inform him that I had been wounded. Given that it wasn’t a serious injury, it was certainly a bit melodramatic – but what did he know?! I often took the farm’s Land Rover, a shotgun and the dogs and spent a lot of time sitting on the sand banks of the Umfolozi River. With the dogs sitting comfortingly around me, I stared blankly into the muddy water as it slid idly past.

Savate … I tried to filter the emotions that swirled through my mind, my thoughts locked in, firmly internalized as I was unable to discuss any of it with anyone. This was possibly the hardest part of clandestine operations. It was almost impossible to discuss the personal aspects without the detail of where and why. And finding someone who would be able to relate to it all to help you come to terms with it was unlikely. The excitement, the pride, the unquestionable camaraderie, the exhaustion, the fear, the bravery and tenacity, the exhilaration, the anguish, the guilt, the grief, the emptiness. The one emotion that slowly came to the fore was the guilt … and surprisingly this was not about the men I had killed. The killing had been easy, too easy. Maybe that was the training, and it was, after all, a fair fight (in fact the odds had been stacked heavily against us). Somehow my ambivalence with this aspect doesn’t worry me. It is an emptiness which I have come to terms with over the years.

Strangely the guilt I carried is that I survived. My close friends Tim Patrick and Heinz Muller didn’t. Tim had a preoccupied, detached look in his eye the last time I saw him, but there again, it was the first time he was going into combat. Heinz knew he was not going to make it … “Justin, jy moet lekker wees” haunted me. The bullet that missed my neck by inches, the one that fragmented before hitting my arm, Captain Erasmus shot dead a couple of metres from me … what determines the throw of the dice? Who knows?! It took me years to find a balance … life is a gift, whether you live for one day or a hundred years … cherish every day you are able to look up and see the deep blue sky, the beautiful green grass and the flitting bird flashing from branch to branch … so full of life and enthusiasm. Embrace it, cherish it, revel in it – above all, find the goodness and the happiness. That’s what those who have passed on would want for us. Grief is a healthy emotion that you can’t and shouldn’t deny, and to dwell on it too long is simply self-pity. Life for them is over. We owe it to them to get on with what is left of ours. Death is unavoidable. When it’s time … its time. Face it, accept it.

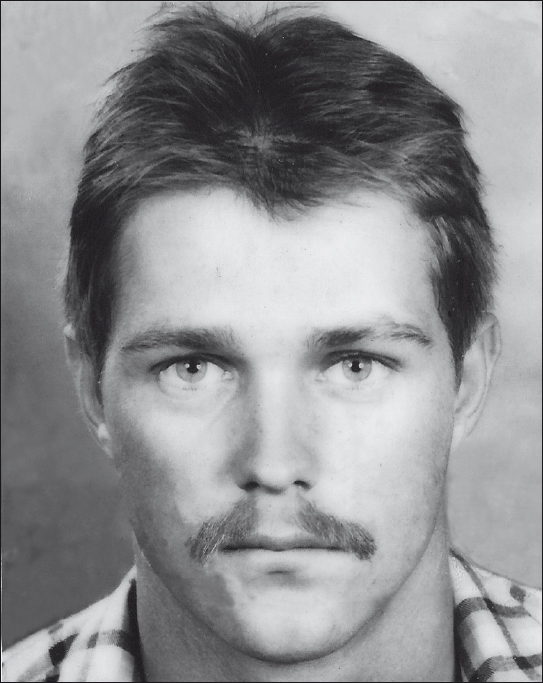

ID photo taken whilst on leave … “I thought I was smiling for the camera … Savate had left its mark.”

Again, I lasted only a week as I struggled to even relate to my own close and very dear family. I am not sure they understood when I tried to explain that I needed to be back on the border and to face what I had to do there until I had completed my National Service. With that obligation behind me, I felt I could then come back and readjust to civvy life … I couldn’t be in between … it needed to be one thing at a time.

So I was back in Rundu early again. This time they didn’t send me home but left me to my own devices. It was good to be back and to settle into the routine with which I had become so familiar. But things in the HQ were now very different. Of five Battalion HQ officers who had gone into the battle, only two of us had survived, Commandant Ferreira and myself. Captain Erasmus, Charl Muller and Tim Patrick didn’t make it. I never even got to write the signals de-brief for Savate as I had for every other Op we’d undertaken. Every time I tried, I just stared blankly at the sheet of paper in front of me. The photo taken for ID purposes while I was on leave seems to say a lot; I thought I was smiling at the time. Savate had left its mark.

We had attacked against overwhelming odds, 350 against what turned out to be possibly as many as 1,400 of the enemy. Fifteen dead and nearly sixty wounded on our side, with radio intercepts later confirming that FAPLA had suffered some 558 killed, wounded or missing. Even given 32 Battalion’s’ personnel losses, militarily it was a significant success. Ferreira’s calculated risk of attacking when he knew that we were outnumbered and when we had lost the element of surprise by not attacking at dawn, paid off, as had his decision not to change the battle plan.

Alpha Company up ahead of us in the HQ had taken the brunt of the fight. They had the widest area to cover and took the most casualties, losing their Company Commander and Intelligence Officer early in the fight. The company was led by the platoon commanders and section leaders, who not knowing their company commander was already dead, were puzzled as to why they couldn’t raise him on the radio. They nonetheless fought their way through to their objectives on the other side of the base, arriving on the far side of the little village battered, bewildered and almost out of ammunition. Pinned down and having left a number of their own dead and wounded behind them, they began to be rightly concerned that these would fall prey to the enemy. Being almost out of ammunition, they were highly vulnerable to counter-attack. Fortunately, Foxtrot Company came to the rescue.

Foxtrot, attacking off to our right under the command of Lt Jim Ross, also came under withering fire, with their descriptions of trees exploding above their heads and leaves falling like snow around them. Despite also taking considerable casualties, they emerged on the other side of the base as an organised and coherent fighting unit. And they certainly appeared to save the day as Jim Ross regrouped his company and came back across to help out the tattered remnants of Alpha Company. His steadfast leadership was welcomed by the Alpha Company platoon commanders and it delivered solid command and control to them in the absence of their own company commander, who they now knew was missing, though they were unaware had been killed.

Willem Ratte had played a key role from his OP (Observation Post) on the eastern banks of the river, directing accurate mortar fire on critical areas needing support and most notably silencing the 14.5mm anti-aircraft gun. The lone air force spotter plane had also been decisive, as this ‘eye-in-the-sky’ with Echo Victor (Major Eddie Viljoen) had given us continuous and critical information regarding enemy movements, making it easier for Ferreira to make his tactical decisions. It had also been able to relay messages when there were communication problems with the smaller VHF sets due to terrain or the instance of commanders being killed.

The desperate nature of the battle illustrated the knife-edge on which the outcome of the assault had teetered, particularly as the full extent of by how much we were outnumbered became apparent. By mid-afternoon we had fired off all our 81mm mortar rounds and had nothing in reserve in case of a counter-attack. And to their superior numbers the enemy had added a show of discipline and considerable courage. Being regular Angolan army troops, they had laid down a blistering, vicious and disciplined field of fire from a well-prepared trench system. In addition, they had chosen to fight and where possible, retreat … but not to surrender.

With the two commanders effectively eyeball to eyeball, it was then that Ferreira’s superior tactical appreciation began to tell. He knew we had taken the southern part of the base, and made the right decision to support Sam Heap’s request to withdraw his company from the northern side of the airfield and regroup with the other two companies on the south. This left the enemy in a precarious position, knowing that there was a large force in control of the commanding high ground to the south of the airfield. It was at this point that they would appear to have lost their nerve. They attempted to break out to the north after mortaring us mid-afternoon, straight into the reconnaissance teams deployed as stopper groups, albeit only thirty men in groups of three. The tenacity with which the vastly outnumbered reconnaissance guys had taken on the retreating enemy had left them confused as to where the attack was coming from, and fostered the illusion that they were up against considerably more men than was the case. Deploying the lone gunship in a desperate attempt at halting the convoy seriously jeopardised the clandestine nature of the whole operation. However, it was a risk worth taking as Ferreira believed our missing men were being held captive, with the intention of FAPLA getting them back to Luanda to display to the world. The damage the single 20mm cannon inflicted on the convoy ensured there was no hope of an organized retreat.

Then Ferreira initiated the convoy chase … with the same élan as Wellington had shown at the Battle of Waterloo when he let loose his cavalry on Napoleon. However, that’s where the similarity ends as we were a far more ragged, tatty looking bunch than those dashing cavalry types! Again, completely outnumbered and against the odds … three Buffels with about fifteen of us against reports of thirty vehicles and some 300 enemy troops. We hit the tail end of what was left of the convoy and they finally disintegrated, splintered and ran. Ferreira’s combat appreciation, his assessment of risk and his timing was uncanny. We had gone up against overwhelming odds and won the day. What strikes me looking back was the tenacity and confidence of the troops, officers and NCOs. It was the unflinching, steady, methodical nature of the men that carried the day for us, testimony to the Battalion’s leadership and the outstanding quality of the troops.

With the Battle of Savate, the irony remains that Three-Two had not been given the go-ahead by Pretoria for the attack. The signal that came through to Commandant Ferreira and Commandant Oelschig was very ambiguous in its directive. The brass back in Pretoria maintained that they had given the go-ahead for the reconnaissance of the base only, yet the wording was such that Ferreira and Oelschig took it as formal approval for a full-scale attack. Be that as it may, in the bigger scheme of things Savate was the turning point for UNITA’s war in the region. It gave them the confidence that South Africa was indeed behind their initiative to dominate the entire south-eastern part of Angola. The domino effect was that other FAPLA towns in the region soon fell to UNITA, and FAPLA withdrew from the region. Strategically and at the time, this was a significant and notable success.