Ops Butterfly

Back in Rundu, I found the planning was getting into full swing for Ops Butterfly and what was to be the first of Ferreira’s ‘Butterfly Ops’. Being September and the dry season, we targeted a group of wells and waterholes across the border about 40km into Angola. At that time of the year, the gooks had no option but to stick close to them for water supplies. This operation was similar in shape and composition to Savate with three companies, a mortar platoon, and a group of our Recces assigned to the order of battle – the big difference was that in this instance we were heliborne – with about ten Pumas and about sixteen Alouette gunships assigned to us. Indeed, it felt as if every helicopter in the air force had been sent out to us! Getting to Eenhana was interesting as we flew in a Dakota from Oshikati sitting amongst the cargo. This big aircraft flew alarmingly low, at just over a hundred feet the whole way. Some half an hour into the flight, the load master pointed out the window … tracer bullets were glowing green and red as they eagerly flicked up at us, before floating lazily away above and behind. Luckily the enemy aimed straight at us and by the time their rounds got to where they had aimed, the aircraft had moved on and was long gone. They hadn’t allowed for what fighter pilots call ‘deflection’ … I wanted to kiss the ground when we landed!

When the attack was launched, the Alouette gunships went ahead, arriving at the Chana Umbi water well to start circling the LZ at about 500 feet with the Pumas coming in low and fast to quickly flare a few feet off the ground and disgorge their troops. The Pumas carried us in to the Landing Zone in three waves, flying ten abreast. It was what I imagined Vietnam to have been like and it was really exhilarating to sit in the open doors of the Puma with our feet on the steps, looking out on either side to see the other choppers flying line abreast at breakneck speed. The HQ element went in on the second wave. As the Pumas settled towards the ground, they would disappear into a mini sandstorm. The pilots must have had to use their instruments to land. There was a light contact on the go just to one side of the chana as we hurried to set up the Tac HQ just inside the tree line. I later learned from captured gooks that we had flown straight over an anti-aircraft gun detachment. They had reported the first wave of choppers to their rear command HQ over their HF radio, asking for permission to open fire when the second wave came in (which was us). They had been ordered not to open fire, but rather make good their escape. When it’s not your time, it’s not your time!!

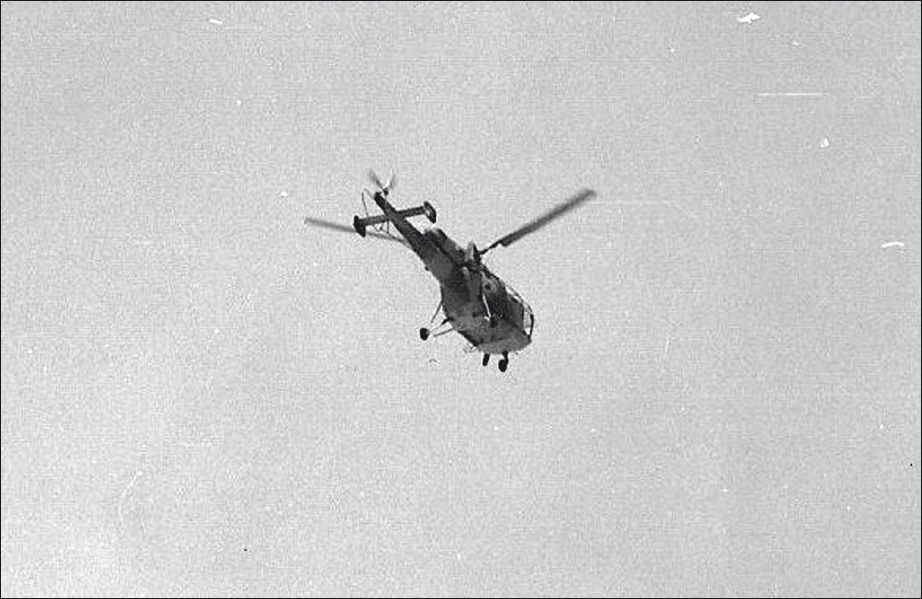

A gook’s-eye view - the belly of an Alouette gunship, its 20mm cannon just visible sticking out of the left-hand side. This is the view a gook would have had while the gunship circled above, seeking him out amongst the trees. Photo by the author while doing a ‘camp’ with 5 Recce in 1983.

There were several water holes in the surrounding area and over the next few days we used the Butterfly Ops concept that Ferreira had devised. There were about eight waterholes within twenty minutes flying time of us. Selecting each in turn, we would send in the slower Alouette gunships so they would get to the waterhole, just as the Pumas arrived to offload the Three-Two troops. With our troops advancing shoulder-to-shoulder and in open order from two sides of the chana, the gunships would circle menacingly above with their 20mm cannons at the ready. The insurgents would be flushed out from their meagre cover and killed by the ensuing air and ground fusillade.

Once the skirmish at the waterhole was over, the bodies would be counted and searched for intel, and the weapons and ammunition collected. Our troops would reload their magazines from the Pumas and while taking a breather, would have a quick bite of a dog biscuit and a drink of water… ready for the next ‘Butterfly’. By this time the gooks that had escaped from the first waterhole, would have run frantically through the bush, arriving at the next one. The fact was that they had no option but to head for them, in that they had to get to the next waterhole in order to make it out of there. The Alouette gunships would by then have refuelled as well and would set off to get to the next waterhole being targeted, again timing it to arrive at the same time as the Pumas did to disgorge their troops. And once again the advancing troops together with the Alouette gunships circling above would begin their deadly work, using the same coordinated tactics as before.

The deadly 20mm cannon, on this occasion in a Rhodesian ‘K-car’. (Courtesy of Max T.)

And so we moved from waterhole to waterhole in the first three days. It was a turkey shoot, killing eighty-four gooks and capturing six in the first three days. Losses on our side amounted to just one dead and three wounded. These casualties were the result of a friendly fire incident when one of our Alouette gunships mistook some Three-Two soldiers for gooks. Other than this unfortunate incident, Butterfly Ops had worked like clockwork. We even had the legendary Neall Ellis arrive, clattering in over the trees in his Alouette gunship, unannounced, and literally out of the blue. He had heard that there was good shooting to be had with Three-Two at Chana Umbi, and he didn’t want to be left out of the action!

On the morning of the second day, someone went to get water from the well in the middle of the chana. When they cranked the handle up, much to their surprise, they discovered a young boy sitting in the bucket that had been suspended at the bottom of the well shaft. The day before, when the Alouette gunships had arrived overhead, the boy had shimmied down the well as there was nowhere else to hide. They never found his parents and he came back with us when we returned to our side of the border. One of our black troops adopted him as his son and he went on to live with his adoptive family at the Buffalo training base. The first night back at an army base on our side of the border, I noticed him staring unblinkingly at the electric light bulb suspended from the Command Bunker’s roof … absolutely mesmerised. It took me a while to realise he had never seen a light bulb before.

The next day, we got word of a small group of gooks located someway off to the east and we dispatched the Alouette gunships and, a little later, some Pumas with troops. Gav Veenstra was with them and during the ensuing firefight they killed about six gooks and captured four of them. It turned out to be their HQ group. It was sobering to discover that two of the dead were women, armed and in uniform. They radioed back to say that they had captured some signallers with their radios intact. I met the choppers as they came roaring back to land in the chana late that afternoon. To my surprise it turned out to be none other than my counterpart … Commander Hindongo, Commander in Chief of Communications for that sector together with his signaller! He certainly outranked me with this grand title, but on the ground we were pretty much on a par! I initially wondered if I should do any of the chivalrous things that I had read about when fellow officers met under these circumstances, but then I quickly realised that it would be a little inappropriate. Trained as a guerrilla fighter in the Ukraine, he very obviously hadn’t done the ‘Officer as a Gentleman’ as part of his training! So our troops dug a pit (two metres square by a metre high) in the middle of our camp, covered it with a mesh of wooden poles and unceremoniously bundled the Commander and his colleagues into it. We placed two guards over them.

I had a careful look at their Russian radios and couldn’t make much headway as to how to get them working. So we pulled the signaller out of the pit, and, giving him a good few persuasive blows to the head, instructed him to fire up the radio. This he did with great alacrity. Spurred on by our success, we then told him to contact his mates and tell them to meet him and his group at a specific time and rendezvous point – where of course we would be waiting in covert ambush. This he cottoned onto and he suddenly started to find difficulty with his radio … more blows, this time with a rifle butt or two. The devilish signaller got the better of us though and the radio suddenly ‘shorted itself out’. By now I could see the comedy in this and I had begun to feel a grudging respect for him. His actions earned him a good beating from the others and he was dumped head first back into the pit.

Each night, all the choppers would fly back across the border into the safety of South West Africa, arriving back the next day soon after dawn. On one of the days the Pumas were trooping our guys into an area around one of the waterholes, an aircraft got hit in both the tail section and tail rotor. The pilot conducted an emergency and landed in a chana while the gunships circled protectively above. The technicians simply took off the entire tail section and brought it back to Chana Umbi, sticking out either side of the open doors of another Puma. A new one arrived the next day and they bolted it on and took off again. Later that same day the air force put on an awesome show for us … it was like watching a huge family of dragon flies escorting their wounded home. The Alouette gunships took off first and circled the chana, test firing their 20mm canons. Then the Pumas lifted off, one of which had the damaged tail section protruding through its open doors, and another lifted off with an entire unserviceable Alouette helicopter suspended beneath it. They had merely removed the rotor blades and attached a rope to the ‘Jesus nut’. With a thunderous roar that engulfed us, and seemed to fill the heavens from horizon to horizon, over twenty helicopters then headed south, with the Alouette gunships circling protectively around the Pumas in the middle. The silence was deafening when they disappeared over the horizon heading south. With the sun setting gently in the west, we were left to our whispered conversations and the inky black African night.

I was hugely impressed the one day to see a four-barrelled, hydraulically operated machine-gun mounted in one of the Alouette gunships. If I remember correctly they might well have been belt-fed, water-cooled Vickers machine-guns of World War One vintage! This was instead of the usual 20mm cannon. The engineer-gunner merely moved two small handgrips connected to a gun-sight and the barrels followed. They test fired it after lifting off and the rate of fire was unbelievable … the sound was something akin to the roaring, frantic tearing of a cotton shirt. The bush he aimed at simply disappeared in a cloud of dust. Incredible! We were absolutely convinced this would win the war for us! Yet we later heard they went back to using the 20mm cannon. The gooks weren’t as scared of the multi-barrelled machine-guns as they were of the 20 mil … the ripping crackle of the multiple machine-guns didn’t frighten them as much as the boom of the single-barrelled cannon and as a result, they stood their ground and shot back against the machine-guns.

Operation Butterfly. (Courtesy of Piet Nortje)

The delightful young lady who kept us company in the command bunker and from whom we drew a great deal of inspiration. She was unanimously crowned ‘Miss Umbi 1980’

We stayed on in the bush for over a month, chasing the spoor of gooks and their shadows. The pin-up that kept us company in the command bunker is pictured above – Commandant Ferreira’s signature heads the list, which is followed by that of the ‘MAYOT’ or the air force liaison officer, mine, Corporal John Bodley, the Command Bunker Signaller, others and then the docs at the bottom. Ferreira played endless games of bridge with the chopper pilots, sitting in the main bunker that had all the radios and maps in it. It measured about three metres by four and two metres deep, with a third of the bunker covered by poles and sand bags. The OC and pilots used a big ammo case filled with mortar bombs as their card table and the smaller cases of small arms ammunition as chairs. This coupled with all the ordnance lying around and its large open design meant I was not sure how effective the bunker would have been had an enemy mortar landed in it, hence my plan was to be sure I wasn’t in there if we got attacked, unless it was absolutely necessary. When things got really boring I remember Ferreira putting a dollop of jam on the ammo case, and then waiting to see how many flies he could attract into his ‘killing field’. When he judged there was the maximum number of flies possible in the killing field, he would smash down the fly swatter, counting with glee the number of flies he had killed in one go. I read some years later how he had used this very same tactic at the Battle of the Lomba River in Angola, where he had lured an entire FAPLA division into his chosen killing field before annihilating them with artillery fire.

A signal came in from our rear Tac HQ at Eenhana that there had been a fight between our black troops and the Parabats. This caused a lot of concern initially, until the details came through later. A Parabat had picked a fight with one of our lightly wounded guys and was quickly joined by his mates in support, at which the rest of our wounded and sick piled out of their tents and into the fight with their legs, arms and heads swathed in plaster casts and bandages. The best part of this was that they saw the Parabats off. Commandant Ferreira laughed about that for days … our ‘sick, lame and lazy’ getting the better of the tough and elite Parabats! I never quiet understood the animosity between the Parabats and Three-Two, but maybe it was something to do with our respective kill ratios. If I remember correctly, the ‘Bats had about 100 kills in that year with 35 of their own dead, whereas we sustained about the same dead with some 700 kills achieved. Maybe that was what pissed them off so much? Thing was, it was an unfair comparison as they were used as fire-force or hot pursuit operations most of the time, and as such continuously ran into ambushes. Three-Two on the other hand invariably took their time and chose their fights with care.

I spent many an evening sitting on the lip of a trench overlooking the chana and talking to Sergeant Gavin Veenstra. With the sun setting off to our right, and sipping a hot fire-bucket of tea, we covered many a topic and had some good laughs. He came from a farm in Mooi River and had grown up with my girlfriend, so we had plenty in common and a lot to talk about. He was a tall, well-built and good-looking guy with curly blond hair. He had the mark of an excellent soldier – mentally and physically strong and as brave as a lion, all of which was balanced by a deep compassion for his fellow man. He usually covered up this compassionate side when around the other tough guys in the recce wing with his easy smile and infectious laugh. For me, he was one of the guys that represented the quintessential soldier … strength, bravery, compassion. It was the guys that had little or no compassion that I didn’t want alongside me in a firefight. They were generally unpredictable and I felt that I couldn’t rely upon them when the chips were down, especially if things turned against us. I would have had ‘Gawie’ Veenstra alongside me any time. He died some years later, hunting down a group of renegade black guys who had robbed the farm next to his back home in South Africa. A fluke pistol shot from over eighty metres hit him in the heart. (Gawie was pronounced ‘Gggavie’ with the Afrikaans guttural, rolling G and a V for the W).

Gawie also reminded me a lot of his friend in the recce group, Sergeant Gavin ‘Gav’ Monn. Being a big strong guy, he was of similar build and character. However, what set them apart was that Gav was often called on to perform the role of company commander, a position usually assigned to a Captain. I think the reason he wasn’t made an officer was because he had a wonderfully straight way of putting his views across – he wouldn’t suffer fools and wasn’t intimidated by rank. He also had a refreshingly straight, frank manner and way in which he dealt with his troops.

We were mortared one night … that spine chilling cough of the big 82mm mortar bombs leaving their tubes just over a kilometre away, followed a few seconds later by the frightening rush of air from the bombs coming down on us, and then the cruummp, cruummp, cruummp as they exploded nearby, seeking out our positions in the night. We had great expectations of some guys with us, who were trying some new fangled triangulation system that would give us the exact direction and distance of the enemy mortars, enabling our own mortars to respond and annihilate them with pinpoint accuracy. We were impressed by this technology and accorded them a certain amount of respect as a result. However, when it came down to the wire, as it were, it didn’t work very well. I think they had slackened from waiting around for weeks in the bush, as when the real thing finally happened they ran around reconnecting wires and things, becoming increasingly flustered and in the process losing the ‘Golden Moment’ they had been waiting so long for. Unable to delay any longer while they sorted themselves out, we opened up with our own 81mm mortars in the general direction of the enemy. With a ‘thoomp–thoomp … thoomp– thoomp’ that hurt your ears and reverberated in your chest, our two mortar tubes, just a few metres away from the HQ, began firing a spread pattern, dropping the bombs over the area from which the enemy were shooting at us. This mortar duel continued for about twenty minutes when suddenly the enemy mortars fell silent.

When the excitement had died down, I unlaced my boots and slid fully clothed into my sleeping bag at the bottom of my slit trench. With the comfort of my rifle next to me, I thought back over the evening’s events. Gazing up at the stars, I felt a huge dose of admiration for these gooks, or more respectfully, these SWAPO guerrillas. Despite having taken a thrashing from our heli-borne troops and gunships over the past few days, they still had the courage and tenacity to come back close enough to get within mortar range…. knowing full well that we would send out our Alouette gunships first thing in the morning to seek and destroy them. Having fired at us early in the evening, they would immediately have started their escape and evasion process, running for the rest of the night, carrying the heavy base plates, mortar tubes and any remaining bombs with them. Spurring them on was the knowledge that if they didn’t cover enough ground before the sun rose, we would catch up with them and their fate would be sealed. Even with these odds against them, they still had the courage and tenacity to give it a go. This particular group’s élan paid off as we lost their spoor midday from a breeze which started mid-morning and blew lightly through the bush, covering their tracks in the soft white sand.

We lived in our slit trenches on the edge of Chana Umbi for over a month with no showers. Ablutions were gentle strolls out into the bush with toilet paper and an entrenching tool in hand. We were nearly driven mad by the flies. Our combat fatigues had long since been caked stiff with dirt on our thighs and backs. If you tried to bend the material it simply cracked. Boy, did we get pissed when we finally got out of Angola and back to the base at Eenhana!

We moved into groups scattered about the chana roughly two hundred metres apart and the Pumas came in waves to take us out, pretty much as we had come in. The junior element of the HQ was near the end, as we kept the Tac HQ comms open using HF radios in case of any incidents that required co-ordination. It was a long day, watching the Pumas coming in, each loading about ten troops with all their kit and then disappearing south. Finally it was our turn. For a good few minutes before we saw them, we heard the unmistakable thud of their approaching rotor blades and then suddenly they broke into view just inches above the tree line, each Puma heading for its allotted group. Ours flared about a hundred feet above us and a hundred metres ahead, before descending and disappearing into its own mini sandstorm. Even before the dust had started settling, we began jogging towards the chopper, Machilla rucksacks on our backs, rifles in one hand and carrying the cases of comms equipment slung between two of us. The big Puma slowly became visible through the murk and with the roar of the blades above, we slung the cases up onto the floor of the cabin. Climbing up, we turned and, shrugging off our Machillas, we sat facing out the door with our feet outside on the step and our rifles held across out laps. We felt the chopper lift off as the pitch of the blades changed and we rose up into the blinding sand storm. Suddenly breaking out of the dust cloud, we had a panoramic view of Chana Umbi, our home for over a month. Perhaps five square kilometres of open ground with the water well in the middle, it was fringed with the dry, brown bush that stretched away, flat and featureless to the horizon. And there just in the tree line was our trusty, fly-infested Temporary Base. Clearly visible in the white sand between the scraggly trees were the command bunker and mortar pits, encircled by the slit trenches of the HQ protection platoon, our recent occupancy evidenced by the sand still freshly churned by our boot prints.

The Puma nosed over, and turning to the south accelerated into a ragged line abreast formation with the other Pumas just above the treetops. Twenty minutes later we flashed out of Angola, back over the cut-line towards the regular army base at Eenhana eagerly anticipating hot showers, massive mess-cooked meals and ice-cold beers. There was a white infantry Major just up from South Africa in charge of the base. He was the real deal, regular Army with snappy salutes, short back and sides, shining boots and perfectly ironed combat fatigues. As much as he tried not to show it, his nose was seriously put out of joint when this unruly mob arrived on his doorstep; wild disheveled hair, unshaven black faces streaked with sweat, with hints of white skin appearing through the ‘black-is-beautiful’, rumpled and filthy camouflaged combat fatigues and worst of all … unpolished boots. And being armed to the teeth with a variety of weapons, mostly stuff the gooks would carry, just didn’t do it for him. And of course the irony was that he failed to notice the one thing that really was of any relevance… the immaculate state of our weaponry, the relaxed discipline amongst us and the easy manner with which we moved about the bush.

In all his wisdom he allowed the HQ element into the base, but not the companies. There were mutterings that this white Major did not want Three-Two in his base because of our black troops. He sent beers out to the platoon leaders as a conciliatory gesture. Big mistake … after a few beers out in the bush that night, and being pissed off about the perceived racial slur against their troops, the white officers and NCOs started firing machine gun rounds and RPGs over the base. With RPGs detonating above him and tracers curving gracefully across his camp, the regular Army Major went berserk. He went rushing around, throwing everything that had anything to do with 32 Battalion out of his base. He then went completely apeshit on seeing how pissed we were when he came to throw out the junior element of the HQ. To add insult to injury, we hadn’t bothered to have a shower or attempt to clean ourselves up before we had started joyfully smashing beers in our faces. Loaded up with all our kit, it took us several attempts to get up and over the embankment that surrounded the base. There was much shouting and hilarity as our heavy Machillas pulled us backwards down the bank as we lost our balance. We finally made it, pushing and pulling each other over the wall, only to tumble down the other side in a jumble of backpacks, rifles, and flailing limbs before ending up in the bushes. It really wasn’t very sporting of the Major at all.

Gathering ourselves together in the dark, we dusted ourselves off and I got everyone into an extended line and we heroically began our advance towards the landing strip. Any semblance of order soon degenerated as we staggered along, bleary eyed and with our ears ringing from the over-abundance of beers we had consumed. Weaving our way over the starlit airfield and moving about forty metres into the bush on the other side, I hastily steered everyone into a rough circle before they collapsed onto the sand. I then stumbled from one to the next telling each what time their guard duty was. Only after a good few kicks could I would get any semblance of a grunted acknowledgement, not that I was in much better shape.

Even after my cajoling to ensure they would all stand their shift at the appropriate time, dawn revealed all eight of our bodies scattered unceremoniously about, each snoring loudly amongst an untidy jumble of kit. Had the guerrillas found us that night – and we hadn’t been snoring so loudly – they might well have left us for dead. As the scorching sun rose mercilessly, the heat dried our tongues and alcohol-soused perspiration began running down our faces. But it was the squadrons of flies that woke us, alighting with delight on our upturned faces and open mouths. We faced a long day with terrible babalases (hangovers) making our heads throb and our eyeballs ache.

However, the real party was about two weeks later in Ruacana. When we left Chana Umbi, some of the companies had patrolled across to the west, coming back across the border from Angola at Ruacana. We had one hell of a party that night in a command bunker they had converted into an impromptu pub next to the big airfield. We were celebrating being alive, being part of Three-Two and our macabre success… we had killed 83 of the enemy. Sometime after midnight, I was unexpectedly informed that my Signals team and I were to leave with the OC at dawn to set up a Tac HQ just off to the east. Now trying to sober up, we stumbled around, still pissed but trying not to let our ‘inebriated ineptitude’ hinder the task at hand. We somehow collected our signals gear together before curling up to sleep alongside our kit. We even managed to get ourselves to the big Puma in the dark before first light and get it loaded with all our kit by the time the OC and the chopper pilots ambled out. We mumbled good morning through bloodshot eyes as the sun cracked over the distant horizon and the dawn broke fresh and crisp around us. As the chopper rose with its blades thudding into the cool air, we welcomed the blast of the wind in our faces as having had only a couple of hours’ sleep, I think we were still a bit pissed.

That was the flight that roared low across a chana and straight over a farmer tilling his field with a donkey. Sitting with my feet out the door and wedged on the step, I looked back to see the donkey galloping wildly across the furrows with the farmer being dragged behind. He was trying desperately to hang onto the plough. He eventually had to let go and he disappeared in a cloud of dust as the donkey bolted off into the bush with the plough bouncing madly behind it. I lost sight of them as we skimmed away, ten feet off the ground.

Having set up the new Tac HQ, we then sat in some nondescript army base right on the cut-line, with a pair of gunships on standby, ready to support some platoons we had in Angola just north of us. It wasn’t particularly successful. We returned to Rundu after about two weeks. It was to be my last Op.