‘Min’ days and a sense of honour

My role in the training of the selection course was over a lot quicker than I had anticipated, and it gave me the opportunity to have two weeks of golden days in the Caprivi. Back in the main Buffalo base, I stayed with the Signallers in a bungalow vacated for my personal use. Set amongst tall trees and lush bush, it overlooked the Kavango River. Every evening we had a good few beers in the very smart Buffalo Base ‘ladies bar’ (only no ladies!) and then slept in late the following morning. We would get up just in time for brunch, which finished at 10am. Fortified with glorious bacon and eggs, and dressed in just a pair of shorts and takkies, we took an R1 rifle to guard against crocodiles and hippos and spent the day tiger fishing. We didn’t catch anything but then again, that wasn’t really the point. We would lie in the calf-deep water where it flowed over a sand bank, with the rifle held just above the water by two forked sticks … not a cloud in the sky, not a breath of wind, with the emerald green water sliding by. Then we would organise a fire in the evenings amongst the tall trees, braaing steaks as we looked out over the beautiful river with its broad sand banks, vast reed beds and surrounding, lush green bush; and then beers in the ‘ladies bar’ again … no matter how pissed we got, we never did get to find those ladies! After the beers, it was often a challenge to find our way through the bush to our bungalows, particularly as we had to be careful not to bump into any elephant, buffalo or hippo in our happily inebriated state.

The evenings not spent in the pub gave me time to spend alone, surrounded by the sounds of the African bush, looking out over the silvery reed beds and the dark majestic river. Sitting quietly outside my bungalow reminded me of my time at the beginning of the year, sitting outside the fishing shack opposite Dirico, looking at the same river, gazing up towards where Willem Ratte and his team were packing explosives under the bridge. Now down at Buffalo, I shared the same solitude, the same magic of the reed beds as I had way back then … the reeds standing silvery still in the moonlight again, rustling gently when the breeze moved over them, as if it were a whisper. It seemed as if they were helping me finally find the answers I had been looking for … about life, death, the war, Three-Two …

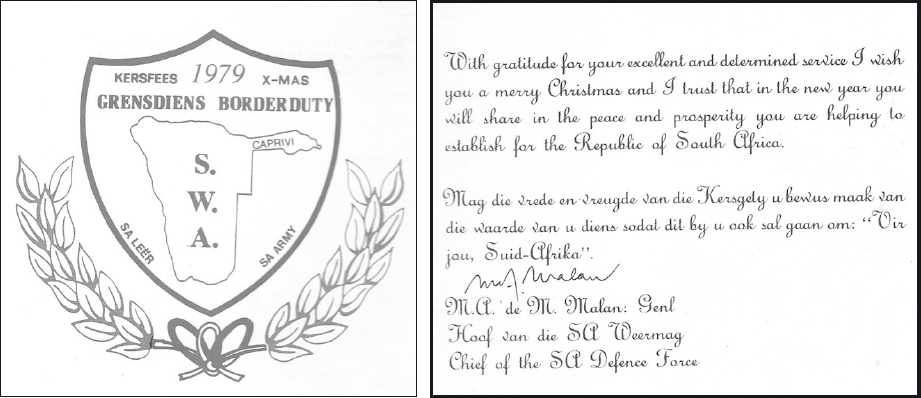

The Southern Cross Fund was a voluntary women’s organisation providing moral support to the South African National Serviceman. Amongst other things, Christmas cards and gifts were sent up to us on the Angola/South West African border and then randomly handed out to the soldiers.

While many issues took a lot longer to come to terms with, the answer to the question of why we were fighting the war in Namibia and Angola had finally begun to emerge. As a Signals Officer I had largely spent my time in various Headquarters and Tactical HQs. This had exposed me to the comments of the brass when they were chatting amongst themselves … and from this I had come to realise that the strategy for the South African Army was simply to keep the war out of South Africa and away from its borders, and in doing so, to allow the political situation to resolve itself back home. Our activities in South West Africa (Namibia) and Angola now made sense to me. And while there were many uncertainties at the time as to the final outcome, given our military strategy, I was certainly very comfortable with the role I had played. I thought back to the braais at Nkongo at the beginning of the year, when we had enthusiastically debated the morality and strategies behind the war. Fuelled by copious amounts of Castle Lager and further energised by youth and innocence we argued long and hard. In particular, I thought of my friend Heinz Muller and his ‘Ons moet net voort fok’ (“We must just fuck forward”) strategy for winning the war. Even with the irony of his death at Savate and my having survived, I couldn’t help thinking with a wry smile what he would have had to say about my newfound wisdom. It all seemed a lifetime ago.

And Three-Two? The mystique of the Battalion and its combat success was what initially attracted me to the unit … but I had come across a whole lot more. Amidst all the complexities of war and the politics behind it, I had discovered a sense of honour. The incredible military capability of the Battalion was only made possible by black and white soldiers working and fighting shoulder to shoulder. It was a beacon of what was fundamentally right in a time characterised by racial segregation and all the friction that ensued, the Battalion’s credo made official with the Trooping of the Colours five years later giving credence to my internalised thoughts … honesty, loyalty, justice. This mutual respect across the colour line was for me perhaps the most significant characteristic of Three-Two. When the shooting starts, it’s not the colour of the man’s skin next to you that counts, it’s what he is capable of. And Three-Two is right up there with the best of the best.

I also came to accept what had puzzled me at first … and that was the realization that I did not hate the enemy. Their political party was known as SWAPO with their military wing being PLAN (People’s Liberation Army of Namibia). They were extremely brave men who were fighting for an honourable cause; that of the independence of their country. I figured they had to rank amongst the finest guerrilla fighters in the world with the effectiveness with which they applied the principles of guerrilla warfare. The courage they displayed with not letting up with their activities in the face of the effectiveness of our anti-guerrilla tactics was exemplary. Missions into South West Africa from their bases deep in Angola were almost suicidal; once they had set out on their mission on foot they had no resupply of food and ammunition, medical evacuation or air support. The terrain they operated in offered little cover in that they were easily spotted from the air, the only thing in their favour being the vastness of the area. If they hit contact with our troops they would briefly stand their ground then they would bombshell and run… and run… and if we caught up with them using vehicles, spotter aircraft and helicopter gunships they died. And yet they were still not deterred, even with the odds being stacked against them and they kept up their war of attrition. So, far from hating them I had a huge amount of respect for their commitment to the principle behind their cause. Nonetheless they were still the enemy and I had my loyalties to my own country, even as confusing as our cause was at the time.

However, be that as it may, that time at Buffalo gave me nearly ten, glorious days of ‘balas bakking’ (sunning your nuts) … time to think, time to relax, and time to have a ‘ jol’. I had a lot of fun one day, scaring the shit out of the guys after a lazy morning’s tiger fishing. Crossing the wide sand bank we had to pick our way carefully through the thick reed bed, never sure what we would find lurking there. I made sure I got a little ahead of them as we headed back towards the bungalows set deep in the thick bush overlooking the river. Being out of view and around a corner, I jumped off the path and burrowed myself under a matted bed of reeds. As the guys were almost on top of me, I heaved the reeds up with my shoulders, letting out a great bellow at the same time. They all let out ear splitting screams and started lashing at the reeds with their spindly fishing rods, valiantly fighting off the buffalo or hippo they thought was attacking them. I laughed even more when I saw their sheepish faces when I threw the reeds off, and had great fun ribbing them about their girlish screams and choice of deadly weapons. I had made sure the guy carrying the rifle was in on my lark or he could have seriously spoilt my day!

The only blot on that time was that we lost one of our black troops to a crocodile. This was a fact of life at Buffalo as the Battalion would usually lose at least three troops a year to these age-old reptiles. He was washing his clothes in the river and was then standing waist-deep, bathing in the water. The croc was so big he only had time to throw his hands in the air and take a deep breath, before disappearing in front of his young son who was standing on the bank. We heard the commotion from our fishing spot farther down the river, and grabbing some hand grenades and jumping into an aluminium assault boat, we roared around tossing grenades into likely spots. We were hoping the croc would let him go, but by now he was more than likely dead. It proved a frustrating, fruitless exercise that left us sombre and introspective. We had been swimming in that very channel a few days previously.

I knew I could only stay under the radar for a limited period of time before having to get back to the Battalion HQ. After a week, signals started to arrive from HQ back in Rundu, questioning my whereabouts. I hitched a lift in a convoy and rode on the back of one of the big, open, Kwevoël lorries. For the first time I got covered in dust as my mates in the platoons had when they had been trooped anywhere. I soon curled myself into a ball on top of the cargo that was loaded on the flatbed, and cocooned myself in my thoughts, while the sun and the wind hammered me in a swirling cloud of dust for hour after jolting hour. I had certainly got used to the cool helicopter rides with the OC and the HQ group!

On getting back to Rundu and the Battalion HQ, the OC was very keen that I sign on for an extra year, or ‘short service’ as it was called. It was a difficult decision to make in the face of having been promoted to full Lieutenant and having been awarded the 32 Battalion Prestige Shield, which was an annual award for the most outstanding junior officer in the Battalion. I had also been cited for the Chief of SADF Commendation Medal for meritorious service (which came through the following year). But I felt I had given it my all and I was looking forward to getting back to civvy street, getting my degree from university, a girlfriend, a home, starting a family … essentially getting on with the life I had fought for.

Thus it was with very, very mixed feelings that I left 32 Battalion and Rundu just before Christmas of 1980. It was particularly difficult to hand in my R1 Assault Rifle. It had seldom left my side and had never let me down.

Rather than fly back home in the Flossie, I had got a lift with Willem Ratte in his little Nissan bakkie. With his arm still adorned with the gut-wrenching pins that stuck out of his arm all over the place, there to heal the wound he had suffered on Ops Chaka a few months previously, we drove from Rundu down through Namibia and all the way to Cape Town. I hadn’t seen any of Namibia except for the Operational Area in the north, and enjoyed the vast open spaces and endless skies. I spent a lot of the time staring into the middle distance, beginning the process of trying to close my mind to the experiences of the past year. We didn’t say much during the two-day drive. We didn’t have to.

I said a quiet goodbye to Willem at the civilian airport and caught a flight back home to Durban.