“YOU REALLY MET MOZART?” Jonah blurted out. He knew it sounded rude, but he couldn’t help himself. “You’re not joking me? You knew him? My mum plays him on the piano sometimes – well, she did, anyway. Mozart. I mean, he’s really famous, isn’t he?”

The old man was frowning. He clearly did not like to be disbelieved, nor to be interrupted. “Indeed, he is famous, Master Trelawney,” he said, clearly impatient now, “probably the most famous and certainly the greatest composer that ever lived. And yes, I had the good fortune and the honour to know him. I do not care to be doubted. This is no fanciful story I am telling you. It is as true and real as I am, as you are, as is that lucky button in your hand. There never was a luckier button. Lucky it was and lucky it is, I promise you, as you shall hear – if you would permit me to continue. Of course, if you are not interested…”

“I am, I am!” Jonah insisted.

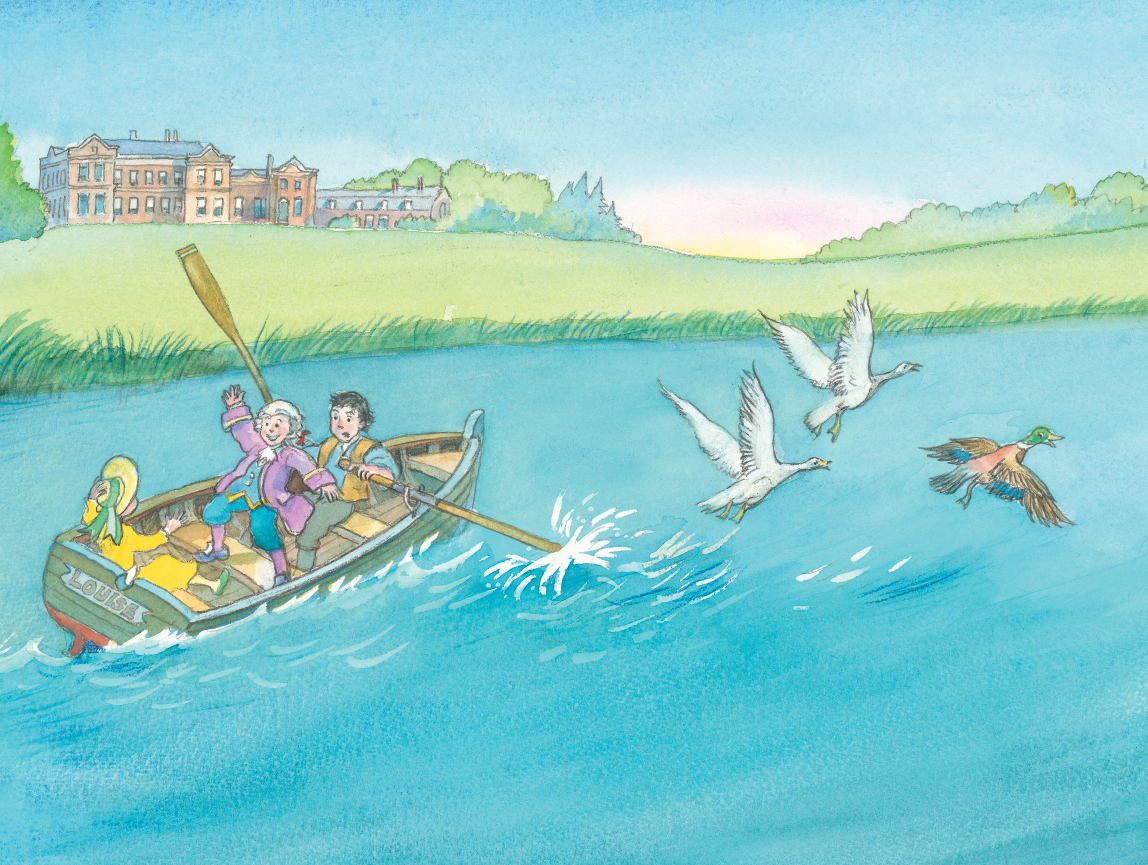

“Very well, very well. If I recall,” the old man began again, “before I was interrupted, I was telling you how I came to assume the responsibility of looking after the young Mozart, of being the little boy’s guardian. I had little time to feel pleased or displeased at my new duties. I was whisked away at once by Wolferl, and dragged down to the riverbank towards a boat that lay waiting in the reeds. It was clear what he wanted. He leapt into the boat, Nannerl jumping in after him. He stood there deliberately rocking the boat dangerously from side to side, shrieking with delight, until Nannerl grasped him firmly and pulled him down beside her, indicating to me to get in and take the oars.

“I had never in my life been in a boat before, never held an oar. I had only watched rowers out on the Thames. I had no choice but to try. Wolferl was bouncing up and down with excitement as I paddled and splashed my way down the river, trying to manage the oars as best I could. Nannerl, I was sure, could see I had never done this before and smiled her encouragement at me. She tried to keep Wolferl seated and still, but he would not do as she bade him, so the boat rocked continuously, which of course Wolferl found all the more exciting and amusing.

“Somehow, miraculously, we survived that first trip on the river, and I managed to bring us home safe and sound. But we were all soaked through from all the splashing by the time we reached the bank. We ran up through the field of cows towards the great house, little Wolferl skipping like the calves and making rude noises at the cows again, and in among the rude noises he would unaccountably burst into sudden song, conducting himself.

“Once in the house he wanted not to be parted from me for an instant, not even to go upstairs to change into dry clothes. He insisted I went with him, and that I was found dry clothing too. That was the moment I began truly to like this Wolferl. He was a sprite, a free spirit, a wild child, but generous-hearted, kind, boundless, full of laughter and endless prattle and merriment. And he loved jokes too, practical jokes, and word jokes especially – most of which I could not properly understand, of course; but I could tell well enough, from his gestures and noises, and from the obvious disapproval of everyone about him, that many were certainly not of a polite nature.

“He was no more polite when we joined with other children and workers living on the estate to play a game of what they called ‘cricket’. This was a game I had never seen or heard of before, and whose rules were quite baffling to me and to little Wolferl, but a game much played, it seemed, at Bourne Park. Wolferl tired very quickly of it, unless he was batting. This part of the game he loved, and he often struck the ball with great enthusiasm and power, but as soon as he was out – and he was usually caught out quite soon – and his bat was taken away from him, he would stamp his feet in rage, and go off to lie in the long grass, where he would sulk and kick his heels. Little Wolferl could be as petulant sometimes as he was charming!”

Jonah had in mind now, as he listened, the picture of Mozart he had seen often on one of his mum’s CDs, rather stiff and stern, with a neat wig. And this was the wild child the old man was describing, who giggled at farting and threw tantrums?

“When the time came for practice on the harpsichord,” the old man continued, “in the great gallery hall downstairs, little Wolferl took me with him and bade me sit beside him as he played. He made it clear by showing me – understanding by now that I could not know what he was saying – what it was he wished me to do. I was to turn the pages of the music for him. I could always sing music a great deal better than I could read it, and anyway had not seen a musical score for some while now, but I did not know how to explain this to him. The notes on the page looked so unfamiliar to me. He looked into my eyes then, and seemed to understand how unsure I was of the right moment to turn the pages. For this he had a most ingenious solution. He would kick me sideways sharply with his little foot as a signal I should turn the page at once. I soon understood the message well enough.

“As he began to play, I noticed there came over this little boy a most extraordinary transformation. All that distracted feverish frolicking left him, and he lived now only for the music he was making. His little fingers danced over the keyboard. Herr Mozart – his father, and also his teacher – sat in a chair nearby, or paced up and down, mostly nodding his approval and conducting; but on occasion he would clap his hands and stop the child from his playing, to instruct and correct him, sometimes rather too harshly, I thought. Little Wolferl endured these interruptions, these admonitions, his eyes filling with tears, but was at once happy again as soon as he could resume his playing. Through it all, Frau Mozart sat at her embroidery, glowing with maternal pride.

“Wolferl insisted I was there at his side every time he played, his little kicks reminding me when to turn the page. As I did so I began to remember all that Mr Montefiore had taught me in my singing practice at the Foundling Hospital. Once learnt, it seemed, reading music is never quite forgotten. Very soon I did not need his little kicks. Wolferl sensed this, I am sure, but he tapped me every time with his foot anyway. He liked doing it, so he did it. And when Nannerl took her turn at the harpsichord, Wolferl did not allow me to turn her pages. Instead he sat himself firmly on my lap, claiming me for his own, and listened to his sister, clapping most enthusiastically when he liked her performance.

“I ate my supper beside Wolferl – he would not have it otherwise – sitting for the first time in my life in a grand dining room with my elders and betters. Wolferl would want to know what everything around him was in English. He would then translate every word into German, and have me speak it, which I found most difficult to do, and which I forgot almost immediately every time. Wolferl, though, remembered every English word I told him, testing himself and his family again and again, and was soon playing with English words, even pronouncing them backwards, and challenging me to recognize them quickly. Often I could not, and nor could anyone else, which gave him much cause for laughter. Wolferl loved merriment above all else, except music, I discovered.

“Every evening when his mother took him away to bed after supper, he complained most bitterly and would not release my hand, begging for me to go with him. His father often became angry with him at this, and Wolferl was forced to go with his mother, dragging his feet and crying. I had never known a more passionate being than this boy.

“Back in my little room over the stable I would sit on my bed, remembering all we had done together each day, the rowing, the music, the frolicking, the merriment. But I was exhausted by all this activity and always fell asleep almost at once. It was at night that the old sadness crept in. I was the happiest I had been for years, but Mrs Ma and Mr Pa and Friend and Paradise filled my dreams, so that I woke still longing for them, and thinking of the chestnut-stall lady in Chiswick who might have been my mother, and the token that would reunite us.

“Every morning I was woken early to tend to my stable work, to feed, water and groom the horses, before leading them out to grass. They were fine animals, but none were as friendly to me as Horace had been. The head groom, Mr Wickens, was a great deal jollier than Boney had been in Mr Hogarth’s stables, and did not spit and curse at all. He worked us hard though. He left the care of all the horses to us, except Frederick. No one but him, I was told, was allowed to go anywhere near Fiery Frederick, as everyone called him. He was truly a giant of a creature, over seventeen hands high and jet black from head to hoof, and, according to Mr Wickens, the best carriage horse in the entire country.

“My work in the stables being done before breakfast, I was instructed every morning to return to the house to be with little Wolferl. He was always eager to see me, eager to play in the fields and go rowing once again on the river, eager to practise his music, eager to learn more English words, and even now to try to speak always in English – imitating me. I had never in my life had a friend like this, so full of fun and affection, so enquiring, so alive to everything and everyone about him. He felt everything so powerfully, at one moment gleeful and joyous, the next plunged into the greatest sorrow and sadness. Tears and laughter followed one another with bewildering speed.

“We all lived in the glow of this small boy. He became the centre of my world at Bourne Park, as he was for everyone else there, especially Nannerl, who doted on him. She was always the only one who could calm his rages – and he fell often into rages – or his fits of wild exuberance. Her greatest joy, I could see, was to be with her little brother, to look after him, but he could not play with her as he played with me. We were boys together, best of friends at once, fast becoming inseparable. Nannerl, though, would be with us almost always, to keep an eye on us both, I thought. And I liked having her there – she was as gentle and calm as Wolferl was wild and wilful. Her English was good enough for me to understand, and like Wolferl she liked to practise speaking it with me.”

Every time the old man spoke of Nannerl, it was Valeria that Jonah had in mind. He pictured her playing with little Wolferl, making her music, smiling at him. She had become part of the story for Jonah.

“One afternoon,” the old man went on, and it was a while now since Jonah had thought of him as a ghost at all, “as we were sitting quietly by the river, watching for the kingfishers that Wolferl loved to see, Nannerl asked me where my mother was. ‘I have none,’ I told her.

“‘And your father?’ she asked.

“‘I have none,’ I replied.

“‘No sister, no brother?’ Nannerl said.

“‘None,’ I told her.

“Wolferl turned to her. ‘Er hat keine Familie?’ he said, tears in his eyes. ‘Keinen Bruder?’ She shook her head. ‘Du bist unser brother, unser friend,’ said little Wolferl, and he threw his arms round my neck. ‘Mein Freund. Mein Bruder,’ he cried. I was touched to my heart by the warmth of their affection.

“Nannerl then asked me all about myself, about where I lived before I came to Bourne Park. So I told her about the Foundling Hospital, my dear Mrs Ma and Mr Pa, and Paradise, my childhood home.

“It was Wolferl who asked me then, through Nannerl, the most difficult question. She translated for him. ‘Wolferl asks: we have the family name of our mother and father – Mozart – and also we are given by them our first names, Wolfgang and Maria. How did you have your names if you do not have a father or a mother?’

“So I told them then how, like all the other children at the Foundling Hospital, I was given a number; that mine was 762; that each of us had a name chosen for us; and that neither Nat nor Nathaniel Hogarth was my real name. I had no real name, for I did not know who my mother and father were. When Nannerl began to explain what I had said, to my amazement, Wolferl began to weep, his hands over his face. Then wiping his eyes he looked up at me, took my hands in his and said, ‘Du bist die Nummer eins für mich, für uns, unser Freund, unser Bruder.’

“Nannerl translated again for me. ‘You are number one for me, for us, our friend, our brother.’ Now I could scarcely forbear from crying myself.

“We spent long happy days together. The three of us roamed the great parklands around the house. Left almost entirely to our own devices, we went back to the house only for meals and music practice, during which he would still tap my leg with his foot, often in rhythm with his playing. From the glances he gave me as he played I knew he still liked to have me always there beside him. Whenever I was with them the family treated me as if I was one of them, the only proper family I had known since Mrs Ma and Mr Pa. And now I had a sister; I had a brother. But still I would lie awake at night, full of longing for the one true family I never had.

“Nannerl it was who warned me one day that Wolferl was sometimes inclined to wander off, and this frightened them greatly. I knew, of course, that this was part of the reason I had been asked to be always with the little boy. Right now, she explained, little Wolferl was so attached to me, his new friend and brother, that he seemed content to stay close and remain with me and with her too; but that we should always be sure to keep him in sight, just in case he began to wander away.

“She was right. He did begin in time to stray more from my side, expecting us to follow him, and this, of course, we did. Between us we kept an eye out for him, and went running after him if he ever strayed too far. More and more, though, he liked to tease and frighten us by hiding, but he was never able to conceal himself for long. His giggling would always give him away in the end.

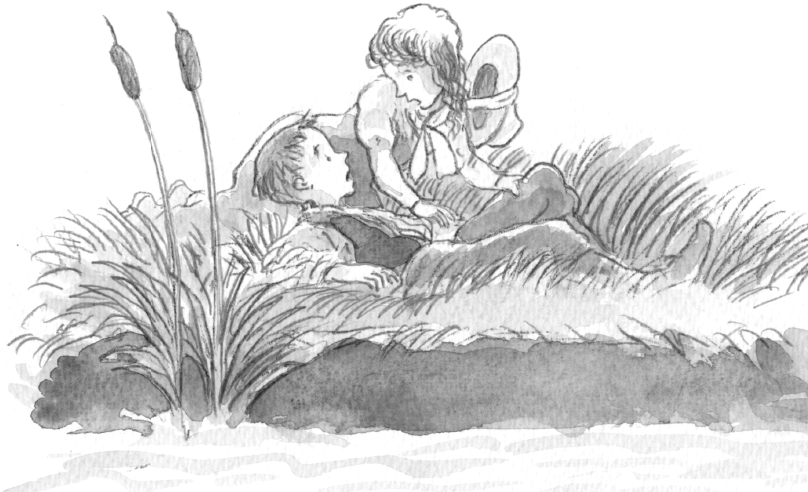

“All was well, until late one sunny afternoon. We were lying on our backs on the riverbank, drowsy in the humming heat, having been out all afternoon in the boat. I had closed my eyes and must have fallen asleep. Suddenly Nannerl was shaking me, shouting at me to wake. ‘Gone!’ she cried. ‘Wolferl, er ist weg. Gone!’”