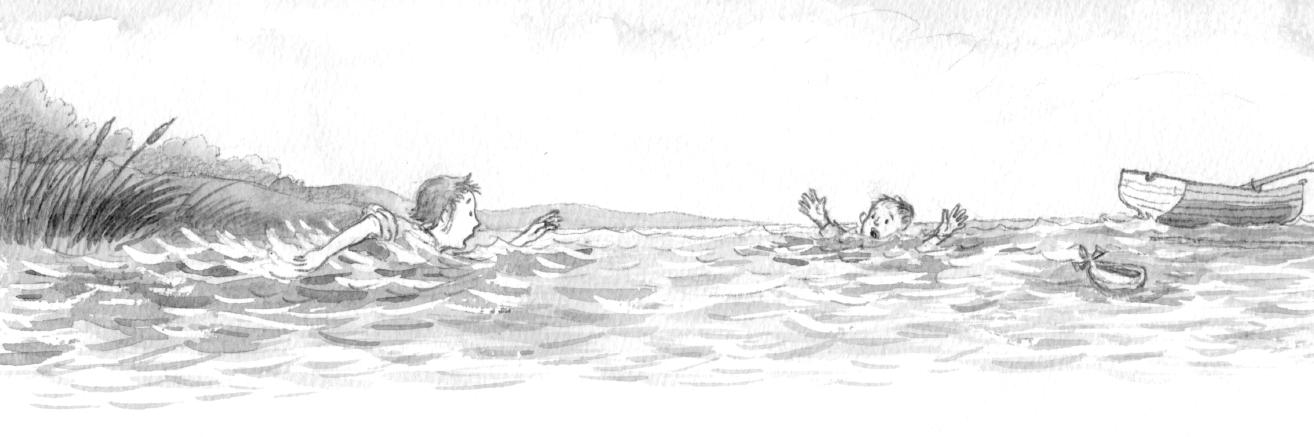

“I FEARED THE WORST. There was the boat, far out in the middle of the river, one oar floating away, but no sign of Wolferl. And then I saw his head further downstream. He was floundering in the water, screaming, arms flailing, sinking, coming up, sinking again. I did not think twice – and I am no hero, I assure you – but ran down to the bank and plunged in. I felt at once the cold of the river gripping me, the weeds tugging at my legs, the flow pulling me. I struck out towards him, kicking myself free of the weeds.

“From where I found the strength I do not know, but I kept swimming, and at last managed to reach him and take hold of him. But such was his panic and distress that I struggled to bring him back to the safety of the bank. I feared that in his terror he would drag us both under. Then, just when I thought all was lost, Nannerl was there to help. Together we hauled little Wolferl out of the river and onto the bank, where he sat and coughed the water out of his lungs. And when at last he had recovered, what did he do, this little friend of mine? He lifted his head, looked at us wickedly, and laughed out loud, as if it had all been the biggest, most enjoyable adventure of his life.

“He was shivering with cold and too weak to walk, so I carried him up through the field of cows and calves towards the house, Nannerl running on ahead calling for help. Even now, little Wolferl, in between his shivering and coughing and spluttering, was pointing at the cows and making again the rude noises he always made whenever he saw them.

“Everyone came running out of the house, Herr Mozart, Frau Mozart, my master, Mr Wickens, and every servant, maid and groom at Bourne Park, it seemed. Herr Mozart relieved me of the burden of little Wolferl at once, as Nannerl continued to tell them all that had happened. Crying through her smiles, Frau Mozart engulfed me in her warm embrace. Sir John ruffled my hair and told me I was a credit to the Foundling Hospital, and to the name of his dear friend William Hogarth; and everyone clapped and cheered me all the way into the house. I was the hero of the hour, and I confess I enjoyed all the attention greatly.

“I shared a hot bath with Wolferl, which shivered the cold out of us, and came downstairs hand in hand with him. The whole household was there waiting for us in the hall, applauding. Nannerl ran up the stairs to greet us, threw her arms round my neck, and whispered to me that she would love me for ever for what I had done. Best of all, Sir John – at the request, he said, of the Mozart family – now relieved me entirely of all my stable duties and told me that, for as long as the Mozart family were staying at Bourne Park, I should live in the house with them, and sleep in little Wolferl’s room; that he himself had insisted upon it.”

“You saved Mozart’s life?” Jonah breathed, unable in his excitement to stop himself from interrupting again. But this time the old man did not seem to mind at all. In fact he seemed positively to bask in Jonah’s admiration.

“Indeed I did, Jonah,” he said, smiling. “Good thing I could swim, eh? If Mr Pa had not taught me as a child, then Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart would never have composed all his glorious music, and the rest of my story – the rest of my life – could never have happened as it did.

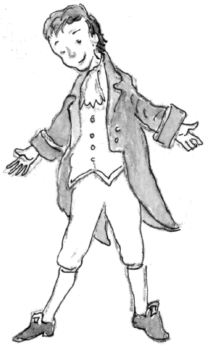

“So,” he went on, “I found myself, a foundling boy, a mere apprentice, suddenly dressed not as a stable boy, but in fine clothes and buckled shoes, living in a grand manner, and treated royally. Every day I continued to enjoy my new-found glory. I was the hero not merely of the hour, but of all the days that followed. I became, for servant and master alike, an honoured guest, one of the Mozart family, best and trusted friend of the little boy whom everyone called ‘Das Wunderkind’, the wonder child; and, of course, I continued to be his page-turner too. I did wonder sometimes what Mr Pa and Mrs Ma would think if they could see me now, and my mother too, who remained in my mind, in my dreams, still the woman on the chestnut stall in Chiswick.

“During these heavenly days, the Wunderkind and his sister would give concerts every evening, and I would be there beside them at the harpsichord. They insisted I took my bows too when the applause came, loud and long, as it always did. Wolferl taught me to bow low and gracefully. We would practise often out in the fields, bowing to the cows, accompanied by his usual rude noises of course. One special concert they dedicated to me, to thank me. My master invited guests from miles around. Wolferl wrote a song for Nannerl and me to sing together, having rehearsed us in our part. Nannerl then sang alone, from the Messiah: ‘Every valley shall be exalted’. They knew this was one of my favourite arias. Can you imagine, Jonah, how happy I was that evening? Seventh heaven? No, seven hundredth heaven!

“But the time came – and of course I knew it was coming and was dreading it – for the Mozart family to leave for London, where Wolferl and Nannerl would be performing their grand concerts. Preparations for their departure were in hand, their trunks packed. I hated to contemplate their going and tried not to dwell on it, but as the day of their departure came ever closer, I could think of little else.

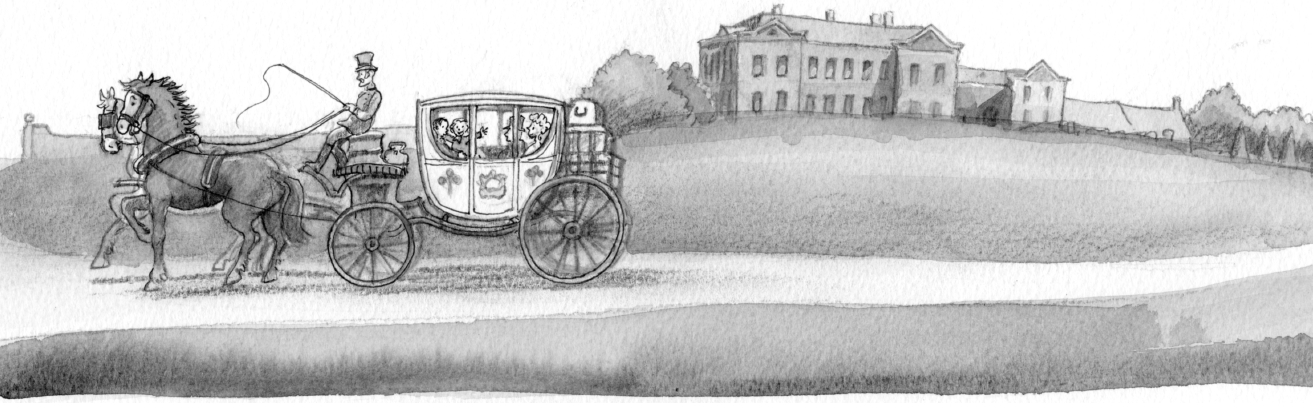

“On the morning they were to leave, I was there in the great hall, with everyone else from the household, waiting to bid them farewell, unsure I could hold back the tears welling inside me. So that I should not betray my emotions, I turned away to look out through the open doors and the pillars of the portico, where the carriage stood ready outside, Fiery Frederick pawing the ground, Mr Wickens standing at his head, waiting. In the hall the family were already taking their leave. Many of the household were in tears, but little Wolferl, to my great consternation, and Nannerl too, seemed quite happy to be going.

“Sir John then made a speech on behalf of us all, wishing them safe and well on their journey, and thanking them for honouring the house by their stay. Herr Mozart, his wife at his side, replied in German, rather stiffly, formally; but Frau Mozart, who seemed to think he had not said enough, spoke a few words in broken English. ‘We shall not forget this place, nor your kindness, nor the river!’ There was much laughter at that, of course. Then they came walking past the household towards the door, saying their farewells. I was the last in line. But they seemed hardly to notice I was there. Indeed they passed me by without so much as a glance. Never in all my life had I felt more heartbroken.

“But just as they were leaving, little Wolferl turned. He was smiling at me, and his family were too. Then everyone burst out laughing – the Mozarts, the whole household, my master. I did not understand. It was a joke of some kind, a conspiracy, that much was obvious. But what it was I had no idea.

“Then my master, Sir John, hushed everyone, and spoke up. ‘Master Hogarth,’ he said, ‘you should know that two days ago Wolferl and Nannerl came to Herr and Frau Mozart and myself, and said that on no account would they play their concerts in London unless their dear friend Nat could be with them at their side. They told us that they considered him to be their brother now and best of friends, and that they would not leave this house without him. After what you have done, Herr and Frau Mozart and I were at once in agreement. So, Master Hogarth, it seems you are to go with them, be with them at their concerts – and, above all, continue to keep young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart safe. Only when they finish their tour in this country in a year or so will you return here to continue your apprenticeship at Bourne Park.’

“Even as he was speaking, much to the joy and merriment of all who were there, Wolferl ran up to me and dragged me off through the great front door. I could scarce believe what had been said, what it really meant, nor what was happening to me. In a daze of bewilderment I found myself sitting with the family in the carriage, Wolferl on my lap, and being driven away down the drive through the parkland by Mr Wickens, with Fiery Frederick snorting and farting all the way – the beginning of a veritable symphony of vulgar sounds that accompanied us much of the journey to London, to Wolferl’s great and giggling delight, and to Herr and Frau Mozart’s considerable embarrassment.

“My stay with the Mozart family in London was to last for over a year. I could not count the number of concerts we played. Everywhere little Wolferl performed, the people came in their hundreds to listen, to wonder at this wonder child. He loved to perform, loved the playing, the fame and the adulation – he would bow again and again, laughing and giggling all the time, in sheer delight of the moment, at the pleasure he had given. But also, I always felt, he was laughing at himself, because even then at that tender age, he knew fame for what it is. He never let it touch him. As soon as the concert and the applause and the adulation were all over, he was himself again, a little boy, a friend, a son, a brother. ‘Fame is like a fart, Nat,’ he told me once. ‘Over quickly and a bit smelly.’”