25

“I just found a picture of you in the archives,” Greta said. “There’s a banner behind you saying WELCOME HOME, but all in all it’s still quite sad. You look so old and worn down that you might be that woman’s uncle, not her brother. And her children don’t seem happy to see you at all.”

“You sound like an actor who’s over-rehearsed her lines,” Ramiro replied. “I suppose you’ve studied the recording of this conversation a dozen times?”

Greta buzzed derisively. “Don’t flatter yourself.”

“No? Your first interaction with the Surveyor, in the middle of a political crisis? You didn’t send that back to the earliest moment that the bandwidth of the oldest channel allowed?”

“I’ve read a summary, of course.” Greta had to make it clear that she’d done her duty. “But I promise you, there wasn’t anything worth studying.”

Ramiro suspected that she was telling the truth; the technical reports would have been more valuable. But even if this conversation had been worthless to her, it didn’t follow that he’d get nothing out of it himself.

“Thank you for the bomb,” he said. “That really came in handy.”

“Any time.”

“So are you still on the Peerless?” he wondered. “Or have you evacuated already?” “I’m where I need to be.”

“In the administrative sense, or the teleological?” He waited, but Greta didn’t dignify that with a reply. “I’m guessing that there are a dozen evacuation craft, one for each Councilor—more or less copied from the Surveyor’s plans. You started building them just after the system was switched on, when you learned that Esilio was habitable and the Peerless might be in danger. You would have liked to improve the design or speed up the construction and make dozens more—but poor Verano found himself unable to innovate that much.”

Greta said, “All you need to know is that the Council will continue to govern across the disruption. The system proved its worth from the start.”

“If you think that the Peerless is going to hit something, why not build an extra channel far away?” he mused. “Ah—that would require some new engineering, wouldn’t it? The first plan put the light path running along the axis, making use of the rigidity of the mountain to stabilize the mirrors. So all you’ve been able to do is repeat that. Ordinarily, the instrument builders would have found a way to keep the mirrors aligned out in the void—but if they’d managed to do that someone would have heard about it long before the event. With twelve separate teams all spying on each other, they can’t even keep a secret from themselves when that’s their only real hope of success.”

“You know a great deal less than you imagine,” Greta said flatly.

“Really? If only you hadn’t had to know everything yourself. You didn’t just turn traveler against traveler: you’ve turned the mere possibility of knowledge into a kind of stupefying drug.”

“There are some flaws in the system,” Greta conceded. “We’ll learn from them. After the disruption, certain things will be reorganized.”

“Reorganized?” Ramiro buzzed. “Will you put all the scientists and engineers in isolation, incommunicado, in the hope that that will solve the problem?”

“Just be patient,” she said. “You’ll see how things turn out.”

“Tell me one thing, then,” Ramiro asked solemnly. “Tell me there’s a pact between the Councilors to shut down all their channels voluntarily. Tell me the disruption’s nothing more than that.”

“I can’t lie to you,” Greta replied. “The disruption is not a voluntary shutdown, it’s proof of a grave threat to the integrity of the Peerless. Knowing that it’s coming will help minimize the danger and ensure the continuity of governance—but beyond that, I know no more than you do.”

Agata brought a basket of loaves from the pantry and passed it around. “I don’t know why everyone’s so gloomy,” she said, breaking the silence. “The whole idea of a collision makes no sense to me.”

Ramiro approached the subject warily. “What if the Councilors and their entourage are prepared to travel to Esilio? They wouldn’t have an easy life there, but over time they might be able to build up their resources to the point where their descendants could protect the home world. There needn’t be a contradiction.”

“I’m not talking about the inscription,” Agata replied. “Whatever hit the Peerless would have to be large enough to disrupt the messaging system immediately, or there’d be a message describing the initial effects of the impact: a fire on the slopes, a breach of the hull—even if people didn’t have time to narrate it, there’d be instrument readings sent back automatically. But anything that large ought to be visible as it approached. Even if it was traveling at infinite speed, it would cast a shadow against the orthogonal stars that we could pick up with time-reversed cameras.”

Azelio was hanging on her words, desperate for reassurance. “What if it comes in from the wrong direction?” he asked.

“There is no wrong direction if you deploy the cameras properly,” Agata insisted. “Suppose this meteor is approaching with infinite speed from the home cluster side. That would render it invisible from the mountain, but if it passed a swarm of time-reversed cameras looking back toward the mountain, they’d see the meteor’s shadow against the orthogonal stars before it was actually present.”

Ramiro wasn’t persuaded. “That all sounds good in theory, but the surveillance network certainly wasn’t that sophisticated when we left. There’d be some serious technical challenges with processing the data fast enough and getting the result back to the Peerless before the impact. It wouldn’t be trivial.”

“And that’s the measure of things now?” Azelio was incredulous. “You’re saying that everything we do to protect ourselves is only possible if it’s trivial? I thought this was all down to probabilities! How likely is it that people who desperately want to solve these problems could just sit at their desks fretting about it, while making no progress at all?”

He turned to Agata for support, but her confidence was wavering. “I spent years in that state myself,” she admitted. “It’s not that difficult to achieve.”

Azelio lowered his gaze. “We should start our own evacuation, then. Bring as many people as we can on board.”

“I’d have no objection to that,” Tarquinia said. “But once we dock, whatever happens to the Surveyor will be out of my hands.” Ramiro had a brief fantasy of the Surveyor orbiting the mountain at a safe remove while evacuees jetted across the void to join them—but unless they were lugging six years’ worth of food there wouldn’t be much point. And even then it could only end badly, once the lucky few had to start turning the rest away.

Azelio’s expression changed abruptly. He buzzed with a kind of pained relief, as if he’d just decided that his fears were not only groundless but embarrassingly naïve. “Whatever else we’re missing,” he said, “we know the Peerless’s location when the disruption takes place. If we were going to be hit by something, we could avoid that just by changing course: we wouldn’t happily steer straight for the meteor.”

Ramiro said, “Maybe they will change course. Maybe they already did. Either way, the disruption still happens.”

“Exactly!” Azelio replied. “So it can’t be down to a collision. If changing the location were enough to stop it happening … it couldn’t happen. On Esilio, we were never forced to do anything against our will, so how could a mountain full of people with no intention of dying be forced to choose a fatal trajectory? Stumbling blindly into a collision would be one thing—but how could it happen with foreknowledge?”

Agata considered this. “I think your argument would hold if we knew the cause with certainty. But it’s not so clear cut when we’re less informed—when we’re not sure that the disruption will be fatal, and we’re not sure that it involves a collision at all.”

Azelio scowled. “So because we can’t know that it’s a collision … it’s more likely that it is?”

“Is that really so strange?” Agata replied. “If everyone on the Peerless was confronted with the certain knowledge that the course they were on was suicidal, then there’s no way they’d persist with it—unless some freakishly unlikely set of events undermined the efficacy of their intentions. With three years’ warning to achieve the necessary swerve, what could possibly stop them? The engines would need to drop off, and every last person capable of improvising any kind of substitute would need to die of some convenient affliction. I don’t believe for a moment that the cosmos contains anything so unlikely.

“But taking an unknown risk is different. If we don’t know exactly what would make us safe, there’s no need for an endless barrage of misfortune to keep us from finding the right solution.”

Azelio abandoned the argument and the cabin fell into a despondent silence. Ramiro almost wished he hadn’t argued against Agata’s first, cheerful verdict. He couldn’t imagine what Azelio was going through, but even his own brief, hallucinatory experiences of fatherhood offered a hint. Nothing could be more harrowing than being forced to contemplate the death of the children you’d promised to protect.

“Maybe the Councilors are going to shut down the system themselves,” he suggested. “Just because Greta denied it doesn’t mean they won’t do it.”

“But why would they?” Tarquinia asked irritably.

“If it’s a choice between that and the destruction of the Peerless,” Ramiro replied, “then I don’t believe they’d choose the latter. Whatever their flaws, they’re not that deranged.”

Azelio was taking no comfort from the theory. “But are they deranged enough to think that that’s their choice? If you can’t avoid a meteor by choosing your trajectory, how can you avoid it just by switching off the messaging system?”

Agata had a different objection. “If they did shut down the system, wouldn’t that be an unsupported loop? They’d only be doing it because they learned that it was going to happen.”

“There’s not much complexity to it, though,” Ramiro argued. “It’s hardly the same as learning a whole new theory of the vacuum from your future self; all they have to do is flick a switch.”

“The Council wouldn’t want the mountain destroyed,” Tarquinia agreed, “but they might well share Azelio’s view about their choices. They’ve come into this looking for a vindication of the system—so I don’t see anything inconsistent if they find themselves receiving three years’ worth of reports from the future that all describe them clinging to their original position: that the whole thing’s a boon, and there couldn’t possibly be any reason to shut it down deliberately.”

Ramiro ran his hands over his face. “Forget the Council, then. Let’s assume that there’s no chance of them causing the disruption. What’s the next most benign explanation?”

“We could do it ourselves,” Tarquinia suggested.

“How?” Azelio demanded. “What could we do that would be harder to see coming than a meteor at infinite speed?”

“I have no idea yet,” Tarquinia admitted. “But at least we’re isolated from the messaging system for a few more stints. We ought to be less vulnerable to the innovation block.”

Agata said, “But in the end, it would only be the shutdown itself that would have driven us to find a way to cause the shutdown.”

“And that’s meant to stop us?” Tarquinia was undeterred. “If that kind of loop really is too unlikely to be true, then we’ll find out eventually. But the only way to know is to try it.”

Ramiro recalled his own farcical attempt to steal the authorship of the fake inscription from her. It still seemed wisest to keep that to himself, but he didn’t need to confess anything to make the case for a more robust strategy.

He said, “There are plenty of people on the Peerless who could have planned this shutdown long before they heard about it.”

“You mean saboteurs?” Agata asked coldly. “The people who murdered the camera team? You want to replace a meteor strike with a bomb?”

“Of course not.” Ramiro spoke more carefully. “Most of the antimessagers found those murders abhorrent, but a group of them could still be planning a way to cause the disruption without hurting anyone. And if they’re intent on using explosives at all, we can try to replace that with something better.”

Tarquinia understood. “We have seven stints to work out a plan of our own, and then we can try to sell it to these would-be saboteurs. That way it becomes a hybrid effort: their motives predate the news of the disruption, but if they’ve left the details too late we might be able to offer them a technological edge.”

Azelio hummed with frustration. “What’s all this talk of replacement? If a meteor is going to hit us, it’s going to hit us! You can devise as many ingenious plans as you like to try to sabotage the system at the very same moment, but if there’s a rock on its way, nothing you do is going to make it disappear.”

“If there’s a rock on its way, that’s true,” Ramiro conceded. “But until we know that there is, why should we assume that? The history of the next twelve stints ends with the messaging system failing; we’re about as certain of that as we can be. Some sequence of events has to fill the gap between that certainty and all the other things we know. So which snippets would you rather the cosmos had on hand to complete the story? Just one, where a meteor hits the Peerless? Just two: a meteor, or a bomb? Making our own preferred version possible won’t rule out everything else—but if we don’t even try, we’ll rule out our own best hope entirely.”

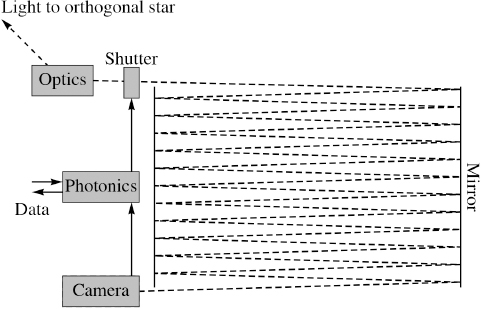

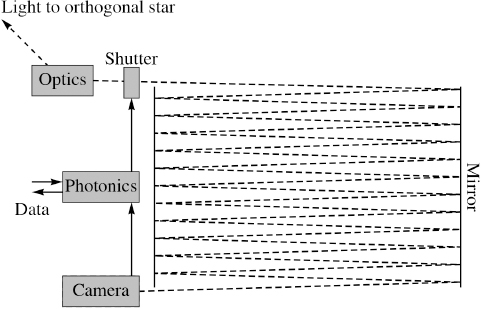

Agata brought a schematic onto her chest. “Whatever the details of the final design they used, each channel must have components something like this.”

Ramiro hadn’t thought about the technical aspects of the system for years, and as he reacquainted himself he was surprised by its apparent fragility. “Disrupt the light for a flicker, and the flow of information is cut. There’s no need to damage anything.” Although the messages were constantly being converted into a less transient form to be boosted and re-sent, that version of the data only endured forward in time—it couldn’t bridge a gap into the past. He’d often pictured the messages as a storehouse of documents, a kind of future-archeological find, but they were much more vulnerable than anything written on paper, or even in the energy states of a memory chip.

“Could we launch some small objects into the external light paths?” Tarquinia wondered. “If each one starts on the mountain close to one of the channel’s outlets, it could probably occult the target star without being picked up by a surveillance camera first.”

Azelio said, “The outlets will have to be on the base of the mountain, won’t they?”

“Yes,” Tarquinia replied. “Unless they’ve turned everything around while we were gone.”

“We’d need to know exactly which orthogonal stars they’re using,” Agata pointed out.

“Maybe our collaborators will have that information already,” Ramiro suggested. “So if we can offer them some miniature automated craft to fly up from the mountain and block those stars, why wouldn’t they use them?”

Azelio said, “So who’s going to build these things without being noticed? They’ll need accelerometers and photonics in order to navigate with any precision. If we make them ourselves on the Surveyor, we won’t stand a chance of smuggling them out when we dock. But on the Peerless, all the workshops and stores will be under surveillance.”

“We could release them before we dock,” Agata suggested. “Send them out to hide somewhere. If they’re small enough, and we time the whole thing carefully, they could pass from the Surveyor to the slopes undetected.”

“And then what?” Azelio pressed her. “They adhere to the slopes somehow, and then crawl toward the base—like insects crawling along a ceiling?”

“Yes.” Agata wasn’t backing down, but the proposal was growing more ambitious by the moment.

“And then later,” Azelio said, “since we won’t know the coordinates in advance, we have to be able to instruct them, remotely, to crawl to a particular take-off point and then fly along a certain trajectory. Without the signal being detected.”

Tarquinia disagreed with his last claim. “If a brief encrypted signal is picked up by the authorities, what can they do about it? So long as they can’t pin down the exact source or destination, mere detection need not be a problem. Even if they take it as a sign that some form of attempted sabotage is underway … they would have had that possibility in mind for the last three years, regardless.”

Azelio hesitated. “So why would they even try to stop us? They know the disruption is going to happen—so unless all this clandestine activity is irrelevant and a meteor is going to be responsible, this is a battle they know they can’t win.”

“They’re not going to give up, any more than we are,” Agata replied. “Do you see any sign in what we’ve heard from the mountain that the Council have resigned themselves to a state of fatalistic powerlessness?”

“No,” Azelio conceded.

“Think of it as a kind of equilibrium,” Tarquinia suggested. “I’m sure there are limits to how far the Council would go to try to stop the inevitable, but there must be limits, too, on how supine they’ll become: they’re not going to shut down the system themselves, or release all the anti-messagers and let them go on a rampage with mallets. They’ve taken a stance and they’re going to pursue it as far as they can. When this is over they’ll be looking for a political advantage in the details of the fight, as much as in the outcome.”

Azelio was looking disoriented. “I want this to work,” he said haltingly. “But every time I stop and think about it, it feels as if all we’re doing is playing some kind of game. Shouldn’t we be trying to build better meteor detectors? If we really are the only people left with any hope of innovating, why not design a device that could actually save the mountain—instead of one for faking its death?”

Agata said, “If we saved the mountain from a meteor, don’t you think we’d know about it?”

“I have no idea.” Azelio rose from his seat. “But what we’re doing now is pointless.” He walked out of the cabin.

In the silence, Ramiro felt his own confidence faltering. “I don’t know how to reason about this any more,” he said. “If it’s a meteor that could actually kill us, isn’t that where our efforts should go? Forget what the messages say or don’t say about it: if we do our best to build something useful, how can that fail to make a difference?”

Agata inclined her head, expressing some sympathy with the impulse. But she wasn’t swayed. “I was the one who tried to argue that there’s no such thing as an undetectable meteor—but what do we have on board for tackling that problem? A single time-reversed camera, and no facilities for building new photonic chips or any kind of high-precision optics. Even if we came up with a glorious new design, how are we supposed to manufacture a whole network of surveillance cameras and get them deployed? They can’t just be drifting around the mountain detecting hazards for their own amusement—if they find something, they have to be able to trigger either a coherer powerful enough to deflect the thing, or start up the engines and make the whole mountain swerve. Do you really think we’d be able to do that in secret?”

“Maybe the Council will finally exercise enough discipline to keep it all quiet,” Ramiro replied.

“If they’re capable of that,” Agata countered, “then they’re capable of doing a vastly better job than we are with the entire project.”

Ramiro gave up. He desperately wanted everything to work in the old way, when he could wrap his mind around a self-contained problem and take it apart without having to think about the entire history and politics of the mountain. But wishing for those days wasn’t going to bring them back. “Then we should go ahead with the star-occulters for our hypothetical saboteurs,” he said. “Find a way to build them, and a way to keep them secret, and then hope that the cosmos takes us up on the offer to explain away the disruption with one simple, harmless conspiracy.”