33

“One day there’ll be a whole set of synthetic influences that we can administer with a photonic device,” Maddalena predicted. “There’ll be tools for every occasion, but the best will be the one that forces the recipient to tell the truth.”

“That’s your vision of the future, is it? That’s what you’ve taken away from all this?” Ramiro stopped himself; whether she was goading him deliberately or not, he was wasting his energy. “Just sign the release form and I’ll get out of your way.”

“There’ll still be a trial,” Maddalena insisted stubbornly. “You know we can implicate her in the sabotage.”

“Whatever you say.”

Maddalena sprinkled dye on her palm and signed the form. Having released the longest-serving untried prisoners, the Council, even in its death throes was still fighting every smaller concession. Nobody in the mountain was quite sure what Tarquinia had or hadn’t done, but compared to four years without trial, four stints did not evoke quite so much passion. Ramiro had had the money for a bond himself, but it had taken all his time to collect the requisite eight dozen signatures from disinterested travelers willing to attest that her ongoing imprisonment offended their sense of justice.

He left Maddalena’s office and headed for the jail.

At the guard post there was more bureaucracy to deal with. Ramiro tried to stay calm as all the paperwork he’d lodged was scrutinized and complained about and the associated photonic records summoned, peered at and misunderstood.

After half a bell of this idiocy, the guard told him, “Just wait now. We’re bringing her out.”

Ramiro watched her gait as she emerged. If she’d been shackled, she showed no sign of it now. He dragged himself forward and embraced her.

“Are you all right?”

“You know what they say,” Tarquinia replied. “There’s no greater honor than following Yalda, mother of all prisoners.” Ramiro wasn’t sure if she was being sarcastic.

“What did you hear about the disruption?” he asked, as they moved away down the corridor, side by side on the guide ropes.

“Explosions at the base. People coming and going from the void. The confused version everyone got in the aftermath—that’s all, no details.”

Ramiro said, “Two of the tubes were breached at the base, but they were resealed in time. Giacomo’s group had their own occulters; they would have torn open the axis if they could.”

Tarquinia had thought things over for too long to be surprised by the betrayal. “What stopped them?”

“Agata,” Ramiro replied. “With a couple of dozen friends. They went out onto the base and tossed the bombs into the sky. Only three light collectors were physically damaged. It was the flash from the explosions that caused the disruption.”

Tarquinia absorbed that in silence.

“They saved the Peerless,” Ramiro said. His gratitude was sincere, but he still felt like a hypocrite.

“Was anyone hurt?”

“Agata lost a lot of flesh. For a couple of stints no one thought she’d survive, but she’s finally recovering.”

Tarquinia hummed softly. “Can we visit her?”

“Of course.”

As they dragged themselves toward the nearest stairwell, Tarquinia recounted her own misadventure. “They let me have the observing time, and everything was looking perfect, but then the most officious busybody among my colleagues decided to check in on me just when I was inspecting the jetpack from the emergency kit. She decided that was suspicious enough to execute a citizen’s arrest; most of the other staff thought she was an idiot, but she had an ally. I was afraid that if I was released, the two of them would be disgruntled enough to make a real effort to get the attention of someone with the power to mention the incident in an official message.”

“And then the Council would have known from the start.” The whole crew would have been under close surveillance from the moment the Surveyor arrived.

“Exactly.” Tarquinia buzzed. “So I ended up having to let myself be detained in a room at the observatory, with the idiots kept busy watching over me and arguing with my colleagues who wanted me released. It was only after the disruption that they managed to get the security department involved.”

They’d reached the level of the hospital; it was just a short walk up-axis now. Ramiro said, “Before we see Agata, there’s something I need to tell you.” He explained his debunking of the hoax. “Don’t be angry with me,” he pleaded. “The whole thing about the ancestors was making her crazy.”

Tarquinia said, “I’m not angry, but you shouldn’t have told her that.”

“Why not?”

“I didn’t make the inscription,” Tarquinia declared. “I went out there to try, but nothing happened: no shards of stone rose from the ground to meet the chisel. I tried different tools, different movements … but I couldn’t unwrite those symbols. If anything, when I left they were sharper than I’d found them—as if all I’d done was make the message less clear for Agata and Azelio than if I’d stayed away completely. I wasn’t the author of those words. Someone else must be responsible for them.”

Ramiro didn’t know if she was telling the truth or just trying to hold on to the benefits of the hoax, but he wasn’t going to start questioning her version of events now. If this was her story, there was nothing he’d seen with his own eyes that contradicted it.

When they entered the hospital ward, Agata caught sight of Tarquinia and called out excitedly, “Ah, you’re free! Congratulations! Come and hear some great news!”

As they approached the sand bed, Ramiro could see that Agata had gained some flesh since his last visit, but she was still limbless. The doctors had told him that she would need every scrag of tissue to support her recovering digestive tract.

“What’s the news?” Tarquinia asked her.

“I just had a visit from Lila and her student Pelagia,” Agata replied. “The innovation block is well and truly over!”

“Yeah?” Tarquinia had probably been expecting to spend the whole visit trying to put the record straight about the inscription, but Agata’s mind was on something else entirely.

“Pelagia’s settled the topology question,” Agata proclaimed. “The cosmos is a four-dimensional sphere. It’s not a torus—it can’t be!”

“This is from your work?” Ramiro asked. “Pelagia found a way to complete the calculations?”

“Not so much complete them as see into my blind spot,” Agata explained. “Listen, it’s simple. A luxagen is described by a wave that changes sign when you rotate it by a full turn. That has no effect on any probability you calculate—so long as you apply the same rotation to everything in sight—because the probability comes from squaring the value of the wave. Minus one squared is one, so the change of sign makes no difference. It only shows up in more complicated experiments where you rotate some things and leave others unaltered.”

Tarquinia said, “I follow that much.”

“Pelagia’s idea just replaces rotations with trips around the cosmos. Suppose the cosmos were a four-dimensional torus, and you carried a luxagen all the way around it in a giant loop. What happens to the sign of its wave? Does it come back unchanged, or does it come back reversed?”

Ramiro frowned. “I can tell that you want us to say ‘reversed’ by analogy, but I thought there had to be perfect agreement around a loop.”

Agata buzzed. “I didn’t want you to give either answer. There could be perfect agreement, or the sign could be reversed: nothing rules out either possibility. If the sign’s reversed, that will be undetectable: everything you can measure locally will still be in perfect agreement.”

Tarquinia said, “Hang on, if the sign changes … where exactly does it change? What’s this special place on the torus where it flips over?”

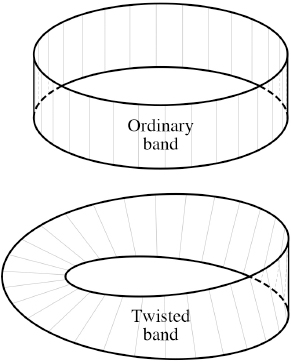

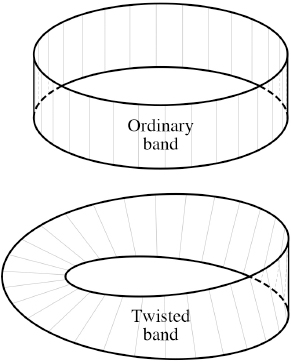

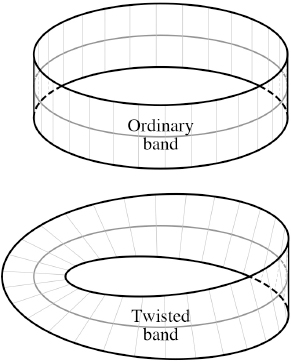

“There is no special place,” Agata insisted. “It’s like cutting open a band and rejoining the ends with a twist: once you’ve glued them together, there’s really nothing special going on at the join. The twist isn’t located there—or anywhere. It’s a property of the whole band.”

Agata began to form a sketch, but Ramiro saw that she was having trouble so he drew what she’d described on his own chest.

“So you’re talking about the cosmos being some kind of … twisted torus?” Tarquinia asked.

“No, not the cosmos,” Agata replied. “The two bands, twisted or not, both have identical circles as their midlines—”

Ramiro added the midlines to his diagram.

“—and you should think of those circles as the cosmos. What happens with the bands is an additional structure that the topology of the cosmos doesn’t fix, one way or the other. It’s all about the luxagens, not space itself.”

Tarquinia said, “All right. I think I’ve got it.”

“Then the next step is to remember that we’re talking about a four-dimensional torus,” Agata continued. “So there are four completely different ways you can travel in a loop. There’s nothing that compels those four routes to have the same effect—it would be perfectly consistent to have a luxagen whose sign changed around some of those loops but not the others. So there are sixteen possibilities altogether: for each loop, the sign might change or it might not.”

Ramiro understood the counting argument, but he couldn’t see where it was leading. “Aren’t these distinctions all invisible, though? They have no effect on any probabilities.”

“They have no effect on probabilities,” Agata agreed, “but if there were sixteen times more choices for the state of every luxagen, that would multiply their contribution to the vacuum energy by a factor of sixteen. Photons give a positive vacuum energy, but luxagens make the vacuum energy negative, and a factor of sixteen would be enough to guarantee that the total energy density in the cosmos was negative, absolutely everywhere.”

Ramiro struggled to recall the implications of this, but Tarquinia beat him to it.

“A negative energy density means positive curvature,” she said tentatively. “But you can’t have a torus that’s positively curved everywhere.”

Agata chirped. “Exactly! You end up with a contradiction. So the cosmos can’t be a torus. But in a four-sphere, every route you might travel can be shrunk down gradually to a tiny circle, and then to a point: a path that goes nowhere. The sign of the wave can’t change along a path that goes nowhere, so there are no extra modes for the luxagens. The vacuum energy stays positive, which means the curvature will mostly be negative—but it also has to change from place to place, because you can’t have uniform negative curvature on a sphere. And because the curvature depends on the entropy of matter, that has to change too. That’s why the cosmos isn’t in a state of equally high entropy everywhere. That’s why there’s a gradient. That’s why we exist at all: with a history, with memories, with an arrow of time.”

Watching her as she spoke, Ramiro couldn’t help sharing her joy. Perhaps the discovery changed nothing tangible, but it vindicated all her years of effort—and it proved that the Peerless was back on course. New ideas were possible again. The paralysis was over.

“And that settles everything?” he asked. “Cosmology is complete now?”

“Not at all!” Agata replied gleefully. “There are still dozens of open questions. People will be working on this until the reunion, and beyond.”

Tarquinia said, “I have some news of my own that you should hear.”

Ramiro had been afraid that the change of subject would go down badly, but Agata listened to the revised version of the last day on Esilio with no sign of hostility.

When Tarquinia was finished, Agata said mildly, “I’m glad you weren’t lying to me, after all.” She glanced over at Ramiro. “And I’m glad you weren’t either, even if you meant to.” It was an infinitely gentler barb than he’d expected.

A doctor approached and suggested that they let Agata rest. Agata glanced down at her shriveled torso, as if she’d forgotten the state of it while they’d been talking. “Not one person has said that I look like I’ve shed twice,” she complained. “I’ve been ready to tell them the names of the children, but the joke’s just not happening.”

Tarquinia placed a hand gently against her cheek. “Get strong. We’ll see you again soon.”

Ramiro shared a meal with Tarquinia in the food hall, then they retired to his apartment.

“What is it that’s troubling you?” Tarquinia asked. “I thought it was the inscription, but Agata was fine about that.”

Ramiro didn’t reply. Better to offer no denials or explanations, and she’d come to her own conclusions about the cause.

“We survived,” she said. “We might have been fools to go along with Giacomo … but if we hadn’t, what would have caused the disruption?”

“So whatever we did was just the way it had to be?” Ramiro had meant to sound sarcastic, but the words ended up more like a plea.

Tarquinia said, “I wouldn’t put it like that. But with everyone clinging stubbornly to their own agendas, it’s a miracle that it ended without a single death. It’s physics that makes us free—binding our actions to our intentions—but in a tight enough corner with enough people refusing to act against their nature, it’s not hard to imagine that the only route to consistency might involve killing them all.”

Ramiro couldn’t keep silent. “Giacomo told me what he’d planned,” he said.

Tarquinia was confused. “When?”

“After you disappeared. I went looking for him, to see if he could get me out into the void.”

“But he couldn’t.”

Ramiro said, “He told me there was no need. He told me that they had more than enough occulters of their own to do the job—and that the job was much more than we’d asked for.”

“So what could you have done?” Tarquinia still wanted to smooth it over. “It’s not your fault that you didn’t have Agata’s idea, and you couldn’t risk going to the Council.”

Ramiro said bluntly, “I wanted it. For a while. I wanted exactly what he wanted.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Because the way things are makes me angry,” he said. “I’m not afraid that men will be wiped off the mountain—I’m afraid that nothing will ever change for us. We’ll keep on being made for the one remaining purpose where we can’t be replaced, and if we try to do anything else with our lives we’ll be treated like mistakes.”

Tarquinia was silent for a while. Ramiro had expected her to be enraged and disgusted, but even if that had been her first impulse she seemed to be searching for another response.

“Do something,” she said.

“I’m sorry?”

“If you want things to change, you’re going to have to do something.”

“Like Pio? Like Giacomo?”

Tarquinia hummed impatiently. “No. Tamara didn’t blow anything up. Carlo didn’t blow anything up.”

Ramiro said, “I’m not a biologist. I don’t know how to fix the problem that way.”

“What do you want for the men who come after you?”

“I want them to have easier choices than I had.”

“That’s a little vague,” Tarquinia complained. “But I’m sure we can work on it. There’s an election coming up, and we haven’t had a single male Councilor for far too long.”

Ramiro drew away from her. “No. Find another punishment.”

“You want change,” she said. “It’s Giacomo’s way, or it’s politics.”

“I’m not too old to study biology.”

“I think you might be.” Tarquinia became serious. “If even a fraction of the men on the Peerless feel that there’s nothing left to do but plant a bomb somewhere, we’re never going to have peace. If you’ve shared that rage, if you understand it, it’s your responsibility to help find a better way.”

Ramiro replied irritably, “And the women who run things have nothing to do with it?”

“I didn’t say that. We’re still insecure, because we know exactly how bad it would be for us if everything unwound. But do you really think the only voice for men on the Council should come from women?”

“Not at all. I’ve voted for male candidates, but they never get a seat.”

Tarquinia said, “Consider it. That’s all I’m asking.”

They shared Ramiro’s bed, but lay apart. Ramiro watched Tarquinia sleeping in the moss-light. He didn’t know if she was telling the truth about the inscription, but he didn’t care; he’d had enough of trying to fit his own life around some supposed future certainty.

Whatever had been written in the rocks on Esilio, in six generations the travelers had discovered everything they needed to return in safety and protect the home world. The hardest task now would be to find a way to live in peace for six more, and reach the end of the journey without throwing everything away.