George Meredith’s challenging late novel One of Our Conquerors (1891) is framed by anxieties over the reliability of self-knowledge. It opens on London Bridge, with a striking and often discussed scene that encapsulates the novel’s main theme: the distinguished and characteristically self-important London financier Victor Radnor takes an unexpected fall on some “sly strip of slipperiness.”1 After a tense exchange with the working-class man who helps him to his feet, he has the sense that an “Idea” has just occurred to him. Yet the nature of the idea remains for him frustratingly elusive, undefined, and ultimately incomprehensible. Throughout the novel Victor Radnor experiences the idea as something “buzzing” at his understanding; it is “like the clapper of a disorderly bell, striking through him, with reverberations, in the form of interrogations” (3). The “Idea” is never presented explicitly to the reader: as Norman Kelvin writes, “how could it be, since Victor himself only feebly discerns it?” Instead, it is “hinted at, darted at, obliquely glanced at with all the electric, apparent negligence that exasperates the unsympathetic reader of Meredith.”2

This aspect of the novel has come under much criticism, even from Meredith’s earliest supporters. James Moffat writes, for example, “The reader is tantalized all through the novel by references to an Idea which is supposed to elude Victor from beginning to end. No novel by a first-rate writer ever began worse, and this Idea is one of its mistakes.”3 Meredith’s technique causes his readers to share many of the same frustrations as his protagonist: Victor Radnor’s irritation that his consciousness cannot grasp his recalcitrant insight is mirrored by the reader’s exasperation with the narrator’s withholding of the nature of the “Idea.” The elusiveness of the “Idea,” however, is central to One of Our Conquerors: one of the underlying concerns of the novel is the repeated inadequacy of introspection in its attempt to attain a full and confident self-understanding. At the heart of Meredith’s famously “difficult” style, in this novel as in others, lies a theory of cognition: Meredith explores the felt contradiction between the failure of introspection and the intense experience of the power of the mind. The difficulty of Meredith’s prose is not an unfortunate artifact of his style: the reader’s experience of cognitive difficulty is, first, an integral effect of Meredith’s attempt to capture the opacity of the mind and, second, a deliberate goal of Meredith’s prose, which aims to train the reader’s mind.

One of Our Conquerors, which I examine more closely at the end of the chapter, in its heightened narrative experimentation marks the culmination of a sustained preoccupation with the problems of consciousness and makes those problems one of its central topics. Looking first at The Egoist, I contend that, whereas critics such as Gillian Beer have regarded the “blindness” of self-knowledge largely as a problem of the figure of the egoist, Meredith shows it to be an inherent problem of self-knowledge (as indeed also of knowledge of other minds). Turning then to his earlier novel Beauchamp’s Career (1876), often considered his first mature novel, I argue that Meredith’s style is shaped by a theory of the relationship between narrative style and cognition that emerges from the broader Victorian reconsideration of the nature of consciousness. Through much of his career, Meredith focuses in his style and, in One of Our Conquerors, in his subject matter on what Kate Flint calls “imperfect knowledge” of mind and self. Although the mind may remain opaque to itself, it is not any less powerful: Meredith attributes the most deeply felt experiences to the work of the mind and develops a narrative style that deliberately intensifies the reader’s cognitive effort.4

It is partly for this reason that, even when George Meredith’s reputation was at its highest, he was never what one might call a popular novelist; it has been said of him that “he is in prose what Mr. Browning is in poetry—the cherished favourite of the few rather than the widely read of the many.”5 He was, and still is, reproached for being too difficult. Popular genres like the sensation novel—bestsellers filled with suspense, transgression, and mystery—were criticized for the way in which they were mindlessly consumed, appealing to the reader’s nerves and emotions. Meredith’s novels, by contrast, were faulted for requiring excessive mental effort and work. Readers complained that Meredith made too constant an appeal to thoughtfulness, that he charged his writing with too many ideas and intellectual abstractions, and that his manner of narrating was too abrupt and allusive to allow the mind to absorb the story comfortably. It might seem surprising, then, that Meredith has much in common with the aims of the sensation novelists: he declares that his objective is to depict his characters in the heat of their emotions and to create an analogously raised pulse in his readers, much as sensation novelists sought to do. While he shares a common aim, his strategy differs markedly: rather than raise the pulse of his readers by taxing their nervous system, Meredith worked to tax their minds.

Meredith responds to many of the same theories of physiology and psychology that shaped the genre of the sensation novel. As discussed in an earlier chapter, these texts were said to act directly “on the nerves” and body of the reader.6 They were thought to conjure up a corporeal rather than a cerebral response. Such claims, of course, depended on a view of reading specifically and of cognition more broadly that could explain the somatic effects of reflection. Automatic responses and mental reflexes were shown by nineteenth-century authors such as Alexander Bain, George Henry Lewes, and E. S. Dallas to explain physiological processes during reading. As Nicholas Dames points out, for these writers reading is, “in short, reflexive: it is an act with ties closer to the autonomic actions of the bodies and the spinal column than to higher cortical activities.”7 Critics of the sensation novel, such as Alfred Austin, claimed that the effect of the physiological responses engendered by such novels was destructive on the mind: “Reading, as it is presently conducted, is destroying all thinking and all powers of thought.”8 These comments suggest that there are two reading modalities—one of sensation, and the other of reflection—that for Austin are mutually opposed; the sensation novel reshapes both.9 Responding to many of the same theories of physiological psychology that shaped this genre, Meredith, it could be said, bridges in his own way the divide between sensation and ideation. Reading, especially difficult reading, in his view intensifies the powers of the mind and, as a result, intensifies the reader’s imaginative, affective, and sensory experience of the novel.

While his difficult and cerebral prose has often been aligned with “reflection,” “meditation,” and “thinking,” his intention was also (as I show in more detail below) to depict his characters in the heat of their emotions and to bring about an analogously raised pulse in his readers. For Meredith there is no contradiction between mental effort and affective intensity, which he saw instead as a relationship of causation. He draws on the very same conception of the ties between cognition and the body as underlie the sensation novel to develop a theory of the novel and of reading that places cognitive effort at its center. My suggestion is that—put in terms of physiological psychology—Meredith dismantles the boundary between sensation and reflection by stimulating the nerves of the reader, not through shocks, but through the strenuous working of the mind.

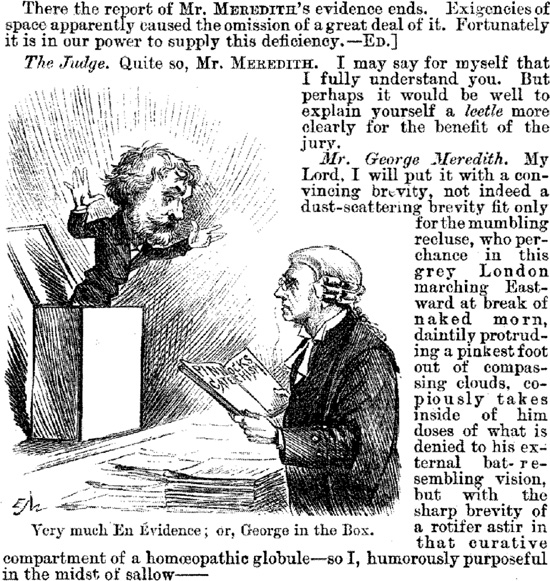

It is not unusual for scholars to read Meredith as a “sensation” novelist, even if this might have struck some of his contemporaries as odd (one early reviewer writes, for example, that Meredith is “anti-sensational to the last degree”).10 Current scholarship has been especially focused on the “sensational” aspects of his novels of the 1860s, such as Evan Harrington or Rhoda Fleming, which are written in a style that he later breaks with. There are certainly such elements in the plots of many of Meredith’s works, and this was not lost on nineteenth-century readers. One Victorian reviewer of Diana of the Crossways notes that “Diana’s beauty and wit; her social, literary, and political power; her unfortunate early marriage; her dangerous intimacy with a distinguished statesman, and the consequent scandal; her betrayal of an important Cabinet secret; the failure of her husband’s attempt to obtain a divorce—all these are facts, and quite sufficient to form the basis of a very ‘sensational’ novel.”11 But Meredith’s novels, even this one, hardly fall neatly under Alfred Austin’s description of the rapid consumption of sensation novels as “novel drinking.” Indeed, his first chapters, or preludes (as in the case of The Egoist), challenge readers in ways that seem designed to weed out those not truly determined to persevere: these texts are far from easily consumable.12 A skit in Punch, on the occasion of his witness testimony at a libel case, parodies Meredith’s abrupt style. It places him in the witness box, where he is called upon to explain the meaning of a series of difficult passages, including ones from One of Our Conquerors. The accompanying cartoon depicts him as “George in the Box,” showing Meredith popping up out of a jack-in-the-box, capturing the surprises readers get from reading his challenging prose.13 Meredith’s constant shifts in pace, perspective, and voice demand that the reader work hard, sometimes even just to understand the plot. So if Meredith’s novels do induce what D. A. Miller describes as “adrenaline effects,” then it is not by way of what Alison Winter in Mesmerized characterizes as “a response that bypass[es] reflection” and in which “the route from nerve to page [is] direct.”14 The reflective element here is clearly not excluded. Instead, the “adrenaline effect” in Meredith lies precisely in the intensity of the cognitive effort, rather than of the emotional sympathy, that is required of the reader.

Many Victorian readers described this effect of his prose as one of virtual, even physical, breathlessness: “Often one feels out of step with him—and out of breath.”15 The testimonials to the “difficult,” “breathless,” even “intoxicating” effect of his novels seem to be based on the belief that even our most physical sensations are in fact the work of the mind. C. Monkhouse in his 1885 review of Diana of the Crossways, for example, calls it “hard reading even to the hard-headed” and maintains that the “swiftness and agility of [Meredith’s] thought requires more intellectual exercise than most readers are able or willing to take.”16 Other contemporary reviewers describe the novels as “fatiguing” and repeatedly liken the reading experience to “exercise.”17 As George Bernard Shaw notes wryly, “It is tolerably easy to understand why Mr. George Meredith’s books are caviare to the general multitude. They … call for mental exercise in a greater degree than perhaps any other novels published.”18 One American reviewer similarly writes, “To read Mr. Meredith is a sort of intellectual gymnastics. Those of us who regard it as a means of grace to memorize a problem in Euclid before breakfast, as a sort of nimble mental exercise—as good for the mind of the writer as playing the scales is for the fingers of the pianist—might substitute with advantage a George Meredith novel.”19 The terms of the debate over Meredith are akin, in this respect, to the concept of “mind work” that was so important to the physiological psychologists: the novels are described as a mode of mental training. As in the psychological writing, mental effort is described in explicitly physiological terms and, as with bodily exercise, mental effort is thought both to fatigue and to strengthen the mind.

“Very much En Evidence; or, George in the Box.” Alluding to his witness testimony at a recent libel case, Punch parodies George Meredith’s difficult style, asking him to testify to its meaning in a mock trial: E. J. Wheeler’s caricature of George Meredith popping up as a jack-in-the-box captures the way Meredith surprises the audience with yet more impossible prose. Punch 101 (19 December 1891): 300. John Hay Library. Brown University Library.

Meredith offers an important key to his theory of cognition in an interview in the Westminster Gazette: “If you are a fine runner and your blood is up,” Meredith observes, “you don’t, in point of fact, feel a half of what you do when lying in bed or sitting in a chair thinking about it.”20 The suggestion is that in the moment of action, of running the race, the runner feels his experience less than when he is remembering or imagining it in his mind. The most intense physical experiences take place, according to this theory, only in anticipation and memory. Meredith’s insight here is that ideation—a mental response that is particularly heightened in the act of reading—can lead to a more intense affective response than the nonreflective experience in the moment. Far from being separate from sensation, then, reflection in fact yields the most powerful sensations. This theory of experience presupposes an interactivity of mind and body in keeping with the view proposed at the time by Victorian psycho-physiologists.21

Meredith’s theory of cognition underlies his most characteristic narrative strategy of decoupling action from intensity of feeling, narrative from plot. As Gillian Beer has written of the paradoxical aspect of these novels, “action becomes stasis: a point of rest.”22 Henry James described Meredith’s avoidance of revelatory movements in his plots as “shirk[ing] every climax.”23 Especially from the 1870s onward, Meredith skips over what he sees as the simplicity of action in his novels (the equivalent of the runner’s race), often bypassing the account of events themselves. Beauchamp’s Career offers some of the clearest examples of this technique: the most important, “action-packed” events in the novel are never described, including a horsewhipping, a duel, and finally even the death of the main character, Beauchamp. Nor are these scenes, like the violent scenes of ancient tragedy, recounted by a messenger or our narrator. Instead, it becomes the reader’s role—and hard work it is—to bridge the information gap, to piece together the fragments, and thus to complete the picture by supplying the “action.” It is this challenging work of piecing together even the basic incidents of the plot that lends the conclusion of Beauchamp’s Career such poignancy, as the reader suddenly recognizes that the protagonist has died in between the final chapters. Meredith’s deliberate omission of central plot elements thus reinforces his commitment to ideation over action in narrative—or rather ideation as action—and forces the reader to provide the real mental action in his novels. We will return to Beauchamp’s Career later in the chapter.

Meredith repeatedly reflects on the slowness of his pacing and the difficulty of his prose, sometimes with self-conscious and self-deprecating humor, at other times pausing to articulate a critical theory of his approach to novel writing. In The Egoist, for example, he remarks, “And if you ask whether a man … can be so blinded, you are condemned to reperuse the foregoing paragraph.”24 This narrator’s aside aligns the character’s blindness with that of the imperceptive reader. The joke, of course, is that Meredith’s prose is such that the reader might very well miss something and feel that rereading a paragraph would be a kind of punishment. After subjecting his readers to one of his most difficult beginnings in One of Our Conquerors—with few exceptions, every contemporary critic comments on the seemingly impossible first paragraph—Meredith offers a defense of his method at the outset of the second chapter, titled self-consciously “Through the Vague to the Infinitely Little.” The opening narrates Victor Radnor’s fall on London Bridge and his tense exchange with a passerby, before entering into a long description, almost in stream-of-consciousness style, of Radnor’s thoughts and sensations as he regains his footing. After the chapter break, Meredith pauses to justify his story’s particularly slow movement:

The fair dealing with readers demands of us, that a narrative shall not proceed at slower pace than legs of a man in motion; and we are still but little more than midway across London Bridge. But if a man’s mind is to be taken as a part of him, the likening of it, at an introduction, to an army on the opening march of a great campaign, should plead excuses for tardy forward movements, in consideration of the large amount of matter you have to review before you can at all imagine yourselves to have made his acquaintance. (10)

Meredith calls attention to his unusual narrative tempo: the narration has followed the pacing of Victor Radnor as he walks across the bridge. With playful self-consciousness, he seems to acknowledge that were the narrative to proceed more slowly than Victor Radnor’s walk across the bridge it would be unfair to the reader. He suggests, however, that “man’s mind” is to be his subject matter and that for this reason he has merely matched the pacing of the narrative to that of Victor Radnor’s train of thought. While humorously acknowledging the length of the book to come—especially after such a slow start—Meredith makes a plea for the reader’s patience. He builds on the ironic image of the title of Victor as a “conqueror,” suggesting that Victor’s march across London Bridge is to be understood not as the campaign itself but as the long preparation for it. In a way that recalls the Sekundenstil experiments of German naturalism or later “real time” cinematic techniques, Meredith’s narrative strategy here is to suggest a one-to-one correspondence between narrated time and reader’s time.25 He acknowledges the difficulty of the novel’s opening and calls attention to the way in which it is an explicit experiment in the relationship between time and narrative.26

Meredith then elaborates a theory of the novel that is analogous to that of the runner mentioned in his Westminster Gazette interview: both accounts suggest that mental effort leads to a heightened intensity of experience. He contrasts his method with that of the “Tale,” which he admits does not place such heavy demands on the reader and has no need of what he calls “tardy” forward movements:

This it is not necessary to do when you are set astride the enchanted horse of the Tale, which leaves the man’s mind at home while he performs the deeds befitting him: he can indeed be rapid. Whether more active, is a question asking for your notions of the governing element in the composition of man, and of his present business here. The Tale inspirits one’s earlier ardours, when we sped without baggage, when the Impossible was wings to imagination, and heroic sculpture the simplest act of the chisel. It does not advance, ‘tis true; it drives the whirligig circle round and round the single existing central point; but it is enriched with applause of the boys and girls of both ages in this land; and all the English critics heap their honours on its brave old Simplicity:—our national literary flag, which signalizes us while we float, subsequently to flap above the shallows. One may sigh for it. (9)

He refuses to set the reader astride “the enchanted horse of the Tale,” which, full of motion and action, “leaves the man’s mind at home while he performs the deeds befitting him”; that is to say that in the tale’s rapid account of the deeds and actions of its heroes, it leaves behind the mind of the characters as well as, we might argue, the mind of the reader. Just as the runner is too involved to think during the race itself and can only experience it intensely in ideation, the reader “leaves his mind behind” in the simplicity of the galloping action of plot-filled tales. Meredith thus asks his readers to reconsider whether the “Tale” is indeed the more “active” form of narrative. He suggests that judgment of “action” in narrative depends on our understanding of the human constitution. Specifically, it depends on our understanding of the “governing element in the composition of man,” by which he means presumably consciousness, thought, or perhaps the will. Characterizing the action-filled “Tale” as the favorite of boys and girls as well as of his unappreciative critics, who celebrate the “simplicity” of such stories, Meredith suggests that we might find his slow narrative the more “active” narrative, precisely because it engages our thought more intensely. He makes a strong claim that “man’s mind” is his subject matter and that this focus drives his unusual narrative technique. Cognitive difficulty is thus central not just to the opening scene with Victor Radnor’s attempt to retrieve the elusive “Idea,” but also to the novel’s method of engaging the reader’s mind.

While criticized for lacking action, for the difficulty of their prose, and for the obscurity of their language, Meredith’s novels have long been admired for their rich treatment of psychology. Sigmund Freud in his Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) turns to George Meredith’s The Egoist (1879) for his main examples of a phenomenon that uncovers the unconscious working of the mind, namely, the slip of the tongue. The focus of the novel is the protracted struggle of Clara to free herself from her engagement to the self-absorbed Sir Willoughby Patterne, a type of male egoist not unlike Edward Casaubon of Middlemarch, Henleigh Grandcourt of Daniel Deronda, or Gilbert Osmond of Portrait of a Lady, to name similar characters from other leading novels of this period. Yearning to be released from the burdensome engagement, Clara briefly fantasizes about having a lover who could take her away, much as Willoughby’s previous bride-to-be Constantina eloped with Captain Harry Oxford. “Unable to speak aloud,” the narrator tells us, Clara “began to speak to herself” of Constantina:

“She did ill. But, oh, how I love her for it! His name was Harry Oxford. […] She did not waver, she cut the links, she signed herself over. Oh, brave girl, what do you think of me? But I have no Harry Whitford; I am alone.” […] The sudden consciousness that she had put another name for Oxford, struck her a buffet, drowning her in crimson. (102)

Freud focuses on Clara’s accidental substitution of the last name of Vernon Whitford, Willoughby’s cousin and friend, whom she comes to marry at the end of the novel, for that of Constantina’s Captain Oxford. Her slip of the tongue (or rather of thought in her mental soliloquy) is of course partly explained by the similarity of names, both ending in “ford.” Yet the underlying significance of her slip is as clear to the reader as it is to Clara herself, bringing about her sudden recognition of her romantic interest in Whitford.

Freud devotes a number of pages in Psychopathology to this moment, using it as a paradigmatic example of lapsus linguae.27 He takes the example from Ernest Jones—who was one of the first influential advocates for psychoanalysis in England and who later became Freud’s official biographer—quoting more than three pages from Jones’s Papers on Psycho-Analysis (1912). Meredith was one of Jones’s favorite literary examples for psychoanalytic principles. Jones contends that Clara’s slip, just one of a series of such slips in The Egoist that he discusses, is a self-betrayal that affords valuable insight into character and motive. Referring to one of Freud’s examples of linguistic slips from The Merchant of Venice, Jones writes that “one of our greatest novelists, George Meredith, in his masterpiece, The Egoist, shews an even finer understanding of the mechanism” than Shakespeare.28 He cites another example from The Egoist, when Clara responds to Sir Willoughby’s patronizing discussion of Vernon Whitford with another slip of the tongue:

“The resolution to do anything unaccustomed is quite beyond poor old Vernon.”

[Clara replies:] “But if Mr. Oxford—Whitford … your swans, coming sailing up the lake, how beautiful they look when they are indignant. I was going to ask you, surely men witnessing a marked admiration for someone else will naturally be discouraged?” Sir Willoughby stiffened with sudden enlightenment. (125)

This is the same lapsus as the first example, Jones explains, and it is “followed by the hesitation and change of subject that one is familiar with in psycho-analysis when a half-conscious complex is touched.”29 Jones considers both examples as illustrations of “the probity of the unconscious mind as contrasted with the duplicity of the conscious one.”30 The slip is symptomatic of a tension between conscious intention and unconscious wishes or desires. Jones makes no distinction between these two examples. Clara’s first slip differs from the second: in the second, she betrays her interest in Vernon Whitford to Willoughby, leading him to stiffen with “sudden enlightenment,” but in the first she is faced with a truth about her own inclinations that has been opaque even to herself. While she may have been duplicitous in her conversation with Willoughby, revealing her truer feelings only by accident, there is no conscious duplicity at work when she begins to “speak to herself.” As in Emma’s sudden recognition of her affection for Mr. Knightly in Jane Austen’s Emma, Clara has been ignorant of her own affections until this moment. Her sudden self-betrayal is a coming to awareness, significantly during a conversation with herself; her self-recognition is thus also experienced as a surprising self-alienation. For Jones, the conscious mind is duplicitous; in this instance, Meredith goes one step further to show how the mind can deceive even itself.

Whereas Jones focuses on the way The Egoist shows how parapraxes, what Freud called Fehlleistungen, inadvertently reveal to others what one would have rather concealed, Meredith is more concerned about what the slip reveals to oneself than what it reveals to others.31 He focuses on the way in which the mind is not transparent even to itself and how such moments reveal to the mind the extent of its own ignorance about itself. Willoughby, in The Egoist, for example, works to maintain appearances and deceive those around him, while as “the egoist” he remains willfully ignorant of his own nature. He deceives himself as much as he does the world: “He desired to be deceived. … Above all he desired that no one should know of his being deceived” (49). This is in part because his sense of self is so firmly grounded in social appearances.32 Clara, however, recognizes Willoughby’s egoism early on. The novel is ostensibly centered on her subsequent protracted struggle to free herself from an unsuitable engagement with an “egoist,” yet it is in many ways as much concerned with Clara’s blindness to her own nature. Over the course of the narrative, her blindness gradually yields to a truer insight into herself. Indeed, the entire novel leads up to her final recognition, “I am an Egoist” (324). What she had recognized early in Willoughby, she remained blind to in herself. It is true, of course, that egoism by its very nature involves a distorted and perhaps distorting view of the self. For Meredith, however, the appeal of the figure of the egoist, in this and other novels, is part of his wider interest in the problem of self-knowledge: the figure of the egoist is a heightened example of a more fundamental difficulty of knowing oneself.33 He revisits the difficulty of gaining a transparent view of the self in many of his novels, beginning with Beauchamp’s Career (1875), through The Egoist, Diana of the Crossways (1885), and especially in his difficult later novels One of Our Conquerors (1891), Lord Ormont and His Aminta (1894), and The Amazing Marriage (1895).

Meredith’s interest in psychological complexity, especially his interest in capturing self-blindness and unarticulated thought, has made him a rich source of examples for psychology and psychoanalysis.34 But even Freud and Jones did not sufficiently appreciate Meredith’s subtlety.35 Early in Diana of the Crossways, Meredith writes that “the brainstuff of fiction is internal history,” a statement that might seem to privilege consciousness in narrative. But as he goes on to show in the novel, the “inner” may be incomplete or delude us, leaving us like an “investigating physician” to examine “the material points of her conduct—indicators of the spiritual secret always. What are the patient’s acts?”36 Almost in the mode of a later behaviorist—skeptical of introspection—Meredith suggests that in the face of the incompleteness of consciousness, we must look to other signs, such as our own actions or our involuntary slips, to understand even our own psychological activity.37 These quotations from Diana of the Crossways make clear that in the depiction of all of the characters in his novels the writer is like a physician who has only incomplete access to the “spiritual secret” within his patient’s mind. In Meredith’s novels, then, the difficulty of knowing the mind compels the narrator and the reader to focus on indirection rather than on introspection.38

Meredith’s writing explores especially what is described in his earlier novel Sandra Belloni (1864) as “the submerged self—self in the depths—.”39 He thus dwells on moments of self-recognition that are also moments of self-alienation. In these moments thought is often felt physically, and knowledge comes through an interpretation of one’s own actions, sometimes mediated by the response of another character to those actions. These moments are not unlike the description of the runner who experiences the intensity of the race in reflection rather than in action. As Miller writes of the chapter “Clara’s Meditations,” it “is her most acute experience of this discontinuity, this failure of the mind to be present to itself … the moment of Clara’s greatest self-clarification is the moment when she is most opaque to herself.”40 Body is never far from brain in Meredith’s depictions: as one reviewer put it in 1889, Meredith “has a way of alluding to our different senses, where delicate taste tells us to forget that we have senses. Instead of ignoring the body he would recognize it as a large factor in human life.” Quoting a phrase from Sandra Belloni, the reviewer defends Meredith, arguing that “it is ‘delicacy of nerve, not weight of brain’ that leads to prudish over-refinement.” Meredith, by contrast, “believes in weight of brain.”41 Meredith’s description of Clara’s “sharp physical thought” (209) is characteristic of the way he renders thinking in physical terms. In his writing there is an inextricable copresence of “body, ‘feelings’ (in both senses), mind, external physical world, and the bodies and minds of other people.”42 Meredith is deliberate in his attempt to capture both the physical and the emotional side of thought. To an American critic he writes,

You say there are few scenes [in my novel]. Is it so throughout? My method has been to prepare my readers for a crucial exhibition of the personae, and then to give the scene in the fullest of their blood and brain under stress of a fiery situation …. Concerning style, thought is tough, and dealing with thought produces toughness. Or when strong emotion is in tide against the active mind, there is perforce confusion.43

Meredith justifies his notoriously “tough” style by arguing that there are contradictions within the psyche and simply that “thought is tough.” As always in his writing, he asserts a correspondence between style and what it conveys: style is itself an important tool that Meredith uses self-consciously to render the “active mind.” Intensity of experience, living in “the fullest of their blood and brain,” is depicted as closely felt in the body. In his attempt to grasp thought, emotion, and cognition, he draws on such techniques as indirection, heavy use of metaphor, and description of sensations and impressions, all of which make his writing unusually challenging. In this sense, it would be misleading to reduce his depiction of the “submerged self” to the elements Freud and Jones focused on: Jones’s “probity of the unconscious” depends on insights afforded to others by the unintentional emergence of the suppressed, but Meredith’s exploration suggests that coming to know one’s own mind is rooted in the matrix of psychological thought that was developed in Victorian England.

When Beauchamp’s Career was published in 1876, it met with quite favorable reviews, although almost all had some reservations. George Bernard Shaw’s review in The Examiner, for example, maintained that “Beauchamp’s Career… whatever its faults may be … is unquestionably one of the best novels of the season. … And this we say while we are not blind to the fact that to enjoy this latest novel thoroughly the closest attention is required, while even then the reader will run the risk of being occasionally perplexed.”44 In the first chapter of Beauchamp’s Career, Meredith introduces the hero Nevil Beauchamp in the first sentence, significantly in a subordinate clause, and then proceeds to describe, not the hero, but the panic in England over fears of a French invasion, not returning to Beauchamp until seven pages into the novel. Meredith’s narrator defines Nevil as practicing “Beauchampism,” which, he explains, “may be said to stand for nearly everything which is the obverse of Byronism.”45 The narrator explicitly imitates this anti-melodramatic stance, calling the story “artless” and plotless.” Meredith is indeed almost unconcerned with plot: if Thackeray’s Vanity Fair is a novel without a hero, many of Meredith’s novels are novels without a plot. In Beauchamp’s Career an indifference to story, a concern with problems, and an intellectual approach are coupled with an indirect, epigrammatic, and clever style, characterized by inferential method, abrupt transitions, abundant analogies, and recondite allusions.

Seemingly regardless of “poetic justice,” Beauchamp’s Career flouts conventions, especially in the arbitrary way it treats the love plots (after wavering between two women, Beauchamp chooses a third about whom the reader has heard very little).46 Much of the action is not narrated and has to be gleaned instead from scattered fragments of conversation. When Beauchamp’s Uncle Romfrey horsewhips the 86-year-old Dr. Shrapnel, for example, an episode that is arguably the turning point of the story, we witness a series of scenes, from which the crucial event must be deduced: we see Romfrey heading to Dr. Shrapnel’s house horsewhip in hand, we share in Beauchamp’s thoughts about Dr. Shrapnel’s ill-health, and finally we witness a conversation in which Cecil Baskelett, Beauchamp’s horrible cousin, triumphantly recounts the horse-whipping to Cecilia Halkett, to whom Beauchamp is devoted. The event itself is never described, but is only indicated by a collage of fragmentary scenes that surround it. This strategy leaves the reader to infer the event from the quite limited information provided. As Beauchamp himself does not witness the horsewhipping, the reader is placed in a position analogous to Beauchamp’s own and is thus brought closer to and even shares in his experience.

For David Howard, looking at similar deviation from plot in Rhoda Fleming, Meredith’s “peripheralism,” or “habit of concentrating on trivial incident and character to the exclusion of and often in place of major event and character,” is compounded by what he terms the pressure of continuing “non-revelation.”47 Non-revelation is, however, more than an avoidance of conventional narration of plot: it lies at the heart of Meredith’s difficult style in Beauchamp’s Career and at the core of his engagement with the nature of consciousness. Not only is plot given by indirection—or through “non-revelations”—so, too, is the consciousness of the protagonists. Toward the end of the novel, Beauchamp becomes violently ill from having contracted fever visiting a working-class man who has himself been ruined by voting for Beauchamp. The illness is not described directly—that is, the reader is not given access to the sick room—but merely suggested by a description of the effect that it produces on others, specifically, from the pain that his feverish cries cause his uncle, Lord Romfrey:

He became aware of the monotony of a tuneless chant, as if, it struck him, an insane young chorister or canon were galloping straight on end hippomaniacally through the Psalms. … It reminded him of a string of winter geese changing waters. … The voice of a broomstick-witch in the clouds could not be thinner and stranger: Lord Romfrey had some such thought. (476)

This description of the ill Beauchamp is filtered through Romfrey’s consciousness and—since Romfrey is one of Meredith’s least imaginative characters—is then filtered again through a series of metaphorical images that do not fully emanate from Romfrey’s mind. With the phrase, “Lord Romfrey had some such thought,” Meredith acknowledges that the imagery is his own interpolation, an attempt to approximate what must have gone through Romfrey’s mind.48 Later, when Romfrey looks back at Beauchamp’s illness, he has no recourse to imagery: “The delirious voice haunted him. It came no longer accompanied by images and likenesses to this and that of animate nature, which were relieving and distracting; it came to him in its mortal nakedness—as affliction of incessant ringing peal, bare as death’s ribs in telling of death (482).”49

In a characteristic move, the narrator describes Romfrey’s move away from imagery by using a metaphor himself, of “death’s ribs in telling of death.”50 Figurative language becomes a tool to narrate aspects of consciousness that elude articulation by the thinker himself: metaphor is thus a means of conveying indirectly a consciousness that is in itself opaque. In a notable instance of “non-revelation,” we never find out what Nevil Beauchamp was ranting about in his delirium (in the one instance in which the “submerged self” breaks through to the surface, the narrative is unable to accommodate it).

Meredith’s heavy use of imagery, of which his critics have often taken note, is thus a technique for capturing an aspect of consciousness that cannot otherwise be narrated: the images are rarely those of the characters but rather those of the narrator.51 In the “Clara’s Meditations” chapter in The Egoist, for example, where we might expect an account of Clara’s thoughts, Meredith offers us instead a series of images. “In a fever, lying like stone, with her brain burning,” Clara’s thoughts are compared to fire, liquids, wind, desert, stone, “for the tempers of the young are liquid fires in isles of quicksand.”52 J. Hillis Miller refers to these as “figures for the unfigurable.”53 Meredith himself gives something of a theory of figurative language in One of Our Conquerors:“It is the excelling merit of similes and metaphors to spring us to vault over gaps and thickets and dreary places. … Beware, moreover, of examining them too scrupulously: they have a trick of wearing to vapour if closely scanned.”54 Figurative language, as Meredith uses it, is a means of bridging a semantic gap: it is able to convey a kind of knowledge that resists analysis.55 In this passage, to convey the power of similes and metaphors, Meredith characteristically offers yet another metaphor that focuses on the almost physical and active effect that figurative language has: it “springs us to vault” over the gaps.

In the opening pages of Beauchamp’s Career, Meredith’s narrator uses another image to explain his narrative method. He describes his strategy as keeping his characters—and in consequence his readers—at blood heat while himself remaining as “calm as a statue of Memnon in prostrate Egypt!” (6). As in the second chapter of his later novel One of Our Conquerors, Meredith is in effect educating his readers, training them how to read the novel that follows, and explaining his own perhaps unusual method. He spells out his twofold aim of remaining an impartial and passive observer, while infusing his characters with a sense of life and immediacy. He explains that

men, and the ideas of men, which are—it is policy to be emphatic upon truisms—are actually the motives of men in a greater degree than their appetites: those are my theme; and may it be my fortune to keep them at blood-heat, and myself calm as a statue of Memnon in prostrate Egypt! He sits there waiting for the sunlight; I here, and readier to be musical than you think. I can at any rate be impartial; and do but fix your eyes on the sunlight striking him and swallowing the day in rounding him, and you have an image of the passive receptivity of shine and shade I hold it good to aim at, if at the same time I may keep my characters at blood-heat. (6)

In this passage, Meredith further represents his role as a medium or transmitter, transforming visible rays of sunlight into audible music and the ideas and motives of men into “blood-heat.”56 Again using an elaborate figure for his explanation of his method, he calls upon the reader to visualize the image of the statue illuminated by the sun (“do but fix your eyes on the sunlight striking him”). The artist is not a final creator, but asks the reader to become an active participant. Meredith describes his aim to maintain an impartial role as conduit: his image of “passive receptivity of shine and shade” suggests that he conveys the “sunlight” of his characters along with those moments of “shade” when there is no song from the statue. His image of the statue of Memnon for his narrative method thus incorporates a place for the failure of narration when without light the statue stays silent. Meredith seems to acknowledge not just his effort at capturing the “ideas of men” when they are at “blood heat,” but also his characteristic omissions and opacity.

One of Our Conquerors presents a culmination of Meredith’s translation of his theory of cognition into a technique of extreme narrative difficulty. Writing in 1897, J. M. Robertson says that “with the exception of Zola’s La Terre—hard reading for a different reason —One of Our Conquerors was the hardest novel to read that I have ever met with.”57 Here Meredith pursues to the extreme the narrative strategies of omission and indirection familiar from his earlier work and also confronts the reader with a strikingly opaque style, opening the novel with the following sentence:

A gentleman, noteworthy for a lively countenance and a waistcoat to match it, crossing London Bridge at noon on a gusty April day, was almost magically detached from his conflict with the gale by some sly strip of slipperiness, abounding in that conduit of markets, which had more or less adroitly performed the trick upon preceding passengers, and now laid this one flat amid the shuffle of feet, peaceful for the moment as the uncomplaining who have gone to Sabrina beneath the tides.

One critic in the Saturday Review in 1891 asks, “Who can follow, for instance, the first paragraph of the novel?” and concludes the essay by stating simply, “This surely is not the way to write.”58 Another writes in the Spectator that “so affectedly grotesque a style would ruin even a good novel, and to describe One of Our Conquerors as a good novel is impossible.”59 Beginning with our protagonist, identified as a gentleman with a waistcoat to match his countenance, the sentence describes his slipping on a piece of vegetable or fruit peel, but not without a series of substitutions, circumlocutions, and verbal contortions. Ending with a mythological metaphor, of the drowned nymph Sabrina, the sentence substitutes an alliterative circumlocution of “some sly strip of slipperiness” for the peel that we learn has subjected previous passersby to the same “trick.” Meredith playfully introduces the novel’s ironic theme of our protagonist Victor Radnor as a “conqueror,” depicting his initial “conflict” and his first failure as a struggle with the gusty wind.

The reader comes gradually to recognize that the language of the opening is not simply characteristic of Meredithian periphrasis and obscurity; rather, it reflects Victor Radnor’s verbal virtuosity and his attempt to seize a world he often cannot comprehend in elaborate metaphors and similes. The mock-heroic tone and his sense of himself as a “conqueror” is as much Victor Radnor’s own voice as it is the narrator’s. In his earlier novel The Tragic Comedians (1880), Meredith had also shown the way his characters either conceal themselves in a torrent of elaborate rhetoric or escape into inarticulate “Dot-and-Dashland”—a phrase that alludes to the telegraph and likewise captures his use of dashes and ellipses—that he also calls “thinking without language.”60 One of Our Conquerors similarly examines and confronts us with the fringes of our comprehension and articulation. The novel’s central concern is with obscurity: from the opening with a protagonist off balance, unable to grasp a thought, opacity of language and thought forms both the subject and the predominant style of the novel.

To see the novel’s style as “grotesque and perverted eccentricity” is, as one critic writes, to ignore the fact “that with Mr Meredith style and subject change or grow together.”61 In a letter to Clement Shorter in 1891 after the publication of the novel, Meredith complains that “it seems, from the general attack on the first sentence of my last novel, that literary playfulness in description is antipathetic to our present taste.”62 Indeed, Meredith playfully introduces us to his rather conceited, “rosily oratorical” (5) City man, with a bit of humor at the character’s expense. Using techniques that come very close to free indirect discourse, Meredith shows his interest, like Freud, in the way language in slips of the tongue can reveal other aspects of a character, and also his fascination with the way language (diction, tone, etc.) more generally permeates our consciousness, even when we do not express it aloud. This accounts for the mannerist, even priggish, tone as well as the obscurity of the novel’s opening. The language and style of the novel render the ways in which the characters understand situations and reflect on them both overtly and in their unspoken responses.

Although the first sentence is unusually difficult, as the paragraph continues Meredith introduces many of the concerns that are familiar from his other work: the description of Victor Radnor’s fall and recovery depicts a classic moment of self-blindness. It shows an egoist in a moment of intense concern about how he is perceived and proceeds to explore at length his experience of alienation from his own mind. Just as Victor Radnor’s unexpected fall in the opening scene on London Bridge is both physical and richly symbolic of his eventual social downfall, his ineffective grasping at his “Idea” presages his gradual mental collapse over the course of the novel. In his earlier novel The Egoist, Meredith had briefly used the image of a man after a physical fall to overcome the shock of dislocation: the concern with appearance leads to a kind of blindness to one’s own condition. The scene in One of Our Conquerors echoes a moment in The Egoist when Laetitia (the loyal local girl who eventually becomes Willoughby’s wife) sees Willoughby right after his (ironically named) bride-to-be Constantia Durham has eloped with another man:

He should have been away at Miss Durham’s end of the county. He had, Laetitia knew, ridden over to her the day before; but here he was; and very unwontedly, quite surprisingly, he presented his arm to conduct Laetitia to the church-door, and talked and laughed in a way that reminded her of a hunting gentleman she had seen once rising to his feet, staggering from an ugly fall across hedge and fence into one of the lanes of her short winter walks: “All’s well, all sound, never better, only a scratch!” the gentleman had said, as he reeled and pressed a bleeding head. Sir Willoughby chattered of his felicity in meeting her. “I am really wonderfully lucky,” he said, and he said that and other things over and over, incessantly talking, and telling an anecdote of county occurrences, and laughing at it with a mouth that would not widen. (20)

Laetitia’s comparison of Willoughby to a man recovering from a fall is revealing. It shows recognition that as with the hunting gentleman, Willoughby has in some sense been wounded and that in this moment he is most concerned with concealing his embarrassment. Like the hunting gentleman still reeling from a physical fall, Willoughby has been put off balance by Constantina’s elopement. The untruth of that gentleman’s “all sound, never better” is echoed in the unfortunate Willoughby’s “I’m really wonderfully lucky.” Only later in the novel does Laetitia come to grasp Willoughby’s concern with appearances: but her choice of comparison to the hunting gentleman suggests that already in this early moment she has seen an aspect of Willoughby’s nature. He is defined, her comparison suggests, by what others see him to be. Meredith emphasizes repeatedly the gaps between what man is existentially and what he is conceptually, that is, when he is imagined by himself and by others.

In One of Our Conquerors, Meredith returns both to the figure of the egoist, this time as a middle-aged man, and to the image of a fall. Meredith develops this same image of the gentleman after a fall, extending it and literalizing it, as Victor Radnor takes a true tumble on “some sly strip of slipperiness.” On getting up, he is most concerned with his appearance and dirty waistcoat, irritated by the smudge instead of grateful for the help:

He was unhurt, quite sound, merely astonished, he remarked, in reply to the inquiries of the first kind helper at his elbow; and it appeared an acceptable statement of his condition. He laughed, shook his coat-tails, smoothed the back of his head rather thoughtfully, thankfully received his runaway hat, nodded bright beams to right and left, and making light of the muddy stigmas imprinted by the pavement, he scattered another shower of his nods and smiles around, to signify that, as his good friends would wish, he thoroughly felt his legs and could walk unaided. And he was in the act of doing it, questioning his familiar behind the waistcoat amazedly, to tell him how such a misadventure could have occurred to him of all men, when a glance below his chin discomposed his outward face. “Oh, confound the fellow!” he said, with simple frankness, and was humourously ruffled, having seen absurd blots of smutty knuckles distributed over the maiden waistcoat. (1)

The novel thus opens with a comic moment—Victor’s awkward slip—that presages the larger downfall that culminates in the novel’s tragic ending. Like Willoughby, Victor is concerned with his appearance: the “absurd blots,” the smudges from the working man’s knuckles on his waistcoat, are embarrassing and make him feel “absurd,” as well. The “absurd blots,” almost a transposed epithet, transfer his feelings about the social discomfort the smudges cause him to the blots themselves. The “absurd blots” also capture an essential contradiction in his social position that remains indecipherable to him: referred to in the novel as a “histrionic self-deceiver” (55), Victor Radnor seeks to establish himself as a prominent exemplar of Victorian society—one of its “conquerors,” or as his name suggests, a “Victor”—regardless of the fact that he has violated the marriage codes of that same society. Since deserting his first wife, Mrs. Burman, many years earlier, he has been living with Nataly, whom even their daughter believes to be his married wife. Yet Mrs. Burman has refused to grant a divorce, leaving him unable to legalize his relationship with Nataly. This hidden transgression means that, as Fabian Gudas puts it in the metaphorical language of the novel, “he cannot wear his white waistcoat proudly, spotless before an applauding world.”63

Victor Radnor’s fall at the opening of the novel has exposed, as with Willough-by’s behavior, his concern with appearance and his sense of superiority. The class collision between Victor Radnor and the worker who helps the City man back on his feet quickly becomes apparent. Placing the reader in closer sympathy with the crowd and the passerby, the exchange exposes to the reader, though not to Victor Radnor himself, his patronizing attitude.

“Oh, confound the fellow!” he said. [ …]

“Am I the fellow you mean, sir?” the man said.

He was answered, not ungraciously: “All right, my man.”

But the balance of our public equanimity is prone to violent antic bobbings on occasions when, for example, an ostentatious garment shall appear disdainful of our class and ourself, and coin of the realm has not usurped command of one of the scales: thus a fairly pleasant answer, cast in persuasive features, provoked the retort—

“There you’re wrong; nor wouldn’t be.”

“What’s that” was the gentleman’s musical inquiry.

“That’s flat, as you was half a minute ago,” the man rejoined.

“Ah, well, don’t be impudent,” the gentleman said, by way of amiable remonstrance before a parting.

“And none of your dam punctilio,” said the man.

Their exchange rattled smartly, without a direct hostility, and the gentleman stepped forward.

It was observed in the crowd, that after a few paces he put two fingers on the back of his head. (2-3)

Such phrases as “amiable remonstrance” and “persuasive features” clearly signal Victor Radnor’s self-deluded condescension. These phrases capture his train of thought in revealing ways. He thinks he is being amiable, yet the working-man exposes Victor’s remark as condescension, and does so by using a word, “punctilio”—a petty point of conduct—that Victor Radnor, furthermore, does not expect from someone of a lower class. Nor does he have any consciousness that his waistcoat is in itself a marker of class difference, which is characterized by the narrator as seeming to the working man “an ostentatious garment” that “shall appear disdainful of our class and ourself” (2).

Like Laetitia’s image of the bleeding hunting gentleman reassuring everyone that he is uninjured, Victor also seeks to reassure those around him that he has not been seriously hurt.64 However, the physical fall on London Bridge that opens the novel stands in for his early transgression of convention (of “punctilio”): in his youth he had married an older widow, whom he left in order to live with Nataly, a younger woman. The novel opens when Victor is hatching three new projects: to marry off his daughter, an innocent girl ignorant that she is illegitimate; to relocate the family to Lakelands, a country mansion that he has secretly been building; and to run for parliament. All of these schemes are doomed because he is willfully blind to the consequences of his error twenty years earlier, when he deserted his wife. He acts for others and for himself as if he were not hurt. The novel is in some ways about the threat of the “blot” of his early actions on his career, on his innocent daughter, and on Nataly, who after having spent a lifetime with him as a married woman, dies before she can officially become his wife. The tragedy of the novel, as Victor ultimately descends into a state of madness, is his inability to accept that he is wounded. Meredith has thus taken the simile of the gentleman who has taken a fall from The Egoist, literalized it and expanded it, while also making it a figure for a larger concern of the novel. The opening chapter examines the way in which his characters are blind to themselves, willfully self-deceiving, as they seek to deceive those around them.

The passage is particularly hard to read because Meredith uses a combination of free indirect discourse and direct discourse (it includes the phrase, “he remarked,” but his comments are given in the third person rather than the first person, as one would expect). The “bright beams” that Victor Radnor nods all around to no one in particular, and the characterization of his “humourously ruffled” response, belied by his exclamation of annoyance, clearly reflect Victor’s own sense of his behavior. The mannerist style more generally reflects Victor’s character and perspective, while it gives us space to recognize the slightly absurd figure he cuts. Meredith begins a number of novels in a similarly mock-heroic tone: Richard Feverel has the dream of liberating Italy on horseback, and Nevil Beauchamp decides to send a challenge to the “Colonels of the French Imperial Guard,” for example. In each, Meredith conveys the earnestness of his central characters, while also making them to look comical in their disproportionate response. Here, too, it would be a mistake not to take into account that the language of the first paragraph of One of Our Conquerors captures Victor Radnor’s nature: the difficulty the reader has in following the story mirrors Victor Radnor’s inability to grasp and articulate his own thoughts.

Tellingly, it is while recovering from his fall that Victor Radnor senses the “Idea” he cannot quite grasp. Over the course of the novel, he returns repeatedly to this elusive thought; the “Idea” remains undefined, incomprehensible, and hard to pin down.65 Again and again, Victor returns to the word “punctilio” and repeats the gesture of putting his fingers to the back of his head. It is not the physical fall that continues to trouble him: rather, as the phrase “the exchange rattled smartly” suggests, it is the interaction with the man that is troubling, with “smartly” here referring to the way it hurts or “smarts.” The “Idea,” the word “punctilio,” and the throbbing bump at the back of his head are indications of his fear of the “absurd blot,” which in his egoism he is never quite able to grasp. Unable to comprehend fully how ludicrous he seems, he nonetheless seems close to recognizing it in the “Idea,” the punctilio bump, through the displaced image of the absurd blot on his waistcoat.

One of Our Conquerors thus extends its analysis of the difficulty of knowing oneself: it goes beyond the way an individual’s egoism distorts his perception of himself and his environment to a more fundamental problem of the failure of introspection. Ramon Fernandez describes something similar when he characterizes the “struggle for life” of Meredith’s characters as a “struggle for lucidity.”66 One of Our Conquerors is not just a study of the failure of lucidity in general but also a study specifically of “non-recognition,” or failed unconscious cerebration. Victor’s sudden vision on the bridge is repeatedly described in the language of the “flash”: “On London Bridge he had seen it—a great thing done to the flash of brilliant results” (415).67 The knowledge that he half perceives in the Idea seems to preclude articulation: “Victor Radnor now perceived the skirts of this idea … Definition seemed to be an extirpating enemy of this idea, or she was by nature shy. She was very feminine; coming when she willed and flying when wanted” (10). Personified as a woman, Victor’s idea seems to have a will of its own, unresponsive to his attempts to retrieve it and verbalize it. We have seen how Walter Hartright in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White is troubled through much of the novel by a similar sense that he has recognized something—the similarity between Laura Fairlie and Anne Catherick—but cannot quite put his finger on what it is.68 Although Hartright is distrustful of the knowledge that unconscious cerebration yields him, eventually he is able to confirm his sense that the two women are connected. Victor Radnor is similarly haunted by an elusive idea, but he remains unable to grasp it.

His failure is not for lack of effort, however: “Victor Radnor was unable to cope with it reflectively. … A short run or attempt at running after the idea, ended in pain to his head near the spot where the haunting word punctilio caught at any excuse for clamouring” (5, 9-10). Unable to grasp the idea directly, right after his fall on London Bridge he experiments with something very like the teachings of William Carpenter and Frances Power Cobbe. So common is the experience, they claim, that when the mind is focused on something else the missing thought or word will suddenly come within our grasp—“Eureka!”—so that we “deliberately turn away, not intending finally to abandon the pursuit.”69 We have recognized that direct questioning of the mind can be counterproductive and that attending to something else can allow us to grasp the idea through unconscious mechanisms instead. Victor Radnor attempts just this strategy:

He tried a suspension of his mental efforts, and the word was like the clapper of a disorderly bell, striking through him, with reverberations, in the form of interrogations, as to how he, of all men living, could by any chance have got into a wrangle, in a thoroughfare, on London Bridge, of all places in the world!—he, so popular, renowned for his affability, his amiability; having no dislike to common dirty dogs, entirely the reverse, liking them and doing his best for them; and accustomed to receive their applause. And in what way had he offered a hint to bring on him the charge of punctilio? (4)

Victor Radnor tries the technique of the physiological psychologists: to stop the concerted mental search for the missing thought and to allow the mind to offer the results effortlessly by its own mechanism. The troublesome word “punctilio” echoes through him, however: the surprisingly pompous phrase resonates in many ways more with Victor’s own punctilious nature. He continues to respond to the haunting word in physiological terms, as reverberations of his fall on London Bridge and perhaps also as an echo of his early transgression in life that runs counter to his otherwise conventional nature.

One of Our Conquerors extends the theme of what Bernard A. Richards calls “curtained knowledge” from the idea that remains elusive to Victor Radnor to the knowledge of her illegitimate birth that he tries to keep from his daughter, Nesta, in the latter part of the novel.70 He pursues the vision of his “Idea” in part because, as he says late in the novel, he thinks it would “cleanse all degradations” (355): his reaction to the word “punctilio” may reveal something of his awareness of his less than punctilious behavior in deserting his wife. Victor Radnor’s fear of the stain that his unmarried state might bring to his daughter echoes his earlier fear of the “absurd blot” on his white waistcoat on London Bridge.

Much of the second half of the novel focuses on Nesta’s choice of suitor and her coming to know and accept her illegitimacy. The novel insists repeatedly on Nesta’s innocence: with “blood incorruptible by dark knowledge” (337), her challenge is to make sense of the dark knowledge of her illegitimacy without allowing it to contaminate her. Whereas Victor Radnor is unable to grasp in his own mind the “curtained knowledge” half given him in his fall, Nesta is better able to unveil the various hidden sources of knowledge that surround her. In fact, when, to the horror of her parents, she befriends the “fallen woman” Judith Marsett, who has since been abandoned by her lover, she seems to pursue the hidden knowledge of her illegitimacy. Described in a series of images of concealment, Judith’s status appears to Nesta as “an iron door shut upon a thing alive” (352): she embodies a “vision of facts below the surface [that] would discolour and disorder her views of existence” (355). But instead of “falling” as Victor does physically, morally, and psychologically, Nesta is able to assimilate forbidden knowledge while remaining unsullied and “irradiated under darkness in the mind.” She convinces Captain Marsett to marry Judith, and thus restores her friend to respectability, while at the same time also cementing her own social respectability through marriage. Where Victor Radnor fails in his ability to grasp the “volatile idea,” Nesta offers a positive counterexample in the quest for self-knowledge: she is described as “laying a finger on a dark thing in the dark” and “getting to have the sight which peruses darkness” (337). At the novel’s outset we are told, “Not until nigh upon the close of his history did she [the Idea] return, full-statured and embraceable, to Victor Radnor” (10). When at the novel’s conclusion Victor is on the verge of grasping it, his mind fails him entirely, leaving him in madness and no nearer to grasping the half-formed “Idea.” Meredith suggests that Victor Radnor’s “Idea” requires an ability “to think radically” (308), something he is by his nature unable to do. Forever eluding Victor Radnor, the “Idea” is by the novel’s conclusion ultimately embodied in his modern, radically thinking daughter Nesta. With an ability to “fl[y] her blind quickened heart on the wings of an imaginative force” (355), Nesta embodies Meredith’s view of possibility and progress: she is able, like his narrative, to “vault over gaps and thickets and dreary places” (159) to make possible a kind of knowledge that can be attained only in imagination and indirection.

George Meredith’s difficult style derives, as I have shown, from his interest in the problems of consciousness and the attempt to develop a style that can be built on them. We might usefully compare Meredith’s style to that of other “difficult” and “thoughtful” writers, such as Henry James. William James, sounding like Meredith’s critics, complained of his brother’s style that “the method seems perverse: ‘Say it out, for God’s sake, … and have done with it.’”71 In Henry James’s dialogues, as in those of Meredith, we can lose track of who is speaking and struggle to make our way through intricate syntax and to identify elusive pronouns or ambiguous allusions. Both Meredith and James convey the nebulousness of thought and speech and strive to render the unarticulated and inarticulate. Meredith lacks a clear stylistic fingerprint such as that found in James’s later works. Meredith’s varied use of imitation, parody, pastiche, and ever-shifting modes—his style altering especially with each new subject—contrasts sharply with James’s much more single-voiced style in his late novels. Yet one of the starkest differences between these two authors is that Meredith’s style, unlike that of the later James, seems to insist self-consciously on the effort of reading. Meredith’s prose is deliberately difficult. He summons a reader whose pleasure is explicitly a matter of critical acumen and resistance to the emotional pull of sensational or sentimental tropes—a reader ready and willing to participate in an “effortful style.”

Henry James also responds to Meredith in terms of the effort and (minimal) reward of reading. Complaining that he has been reading the “final furious band of the unspeakable Lord Ormont” only “at the maximum rate of ten pages—ten insufferable and unprofitable pages, a day,” James declares that “it fills me with a critical rage, and artistic fury, utterly blighting in me the indispensable principle of respect.”72 He complains that the effort required to read the novel is too great:

I have finished, at this rate, but the first volume—whereof I am moved to declare that I doubt if any equal quantity of extravagant verbiage, of airs and graces, of phrases and attitudes, of obscurities and alembications, even started less their subject, ever contributed less of a statement—told the reader less of what the reader needs to know. All elaborate predicates of exposition without the ghost of a nominative to hook themselves to; and not a difficulty met, not a figure presented, not a scene constituted—not a dim shadow condensing once either into audible or into visible reality—making you hear for an instant the tap of its feet on the earth. Of course there are pretty things, but for what they are they come so much too dear, and so many of the profundities and tortuosities prove when threshed out to be only pretentious statements of the very simplest propositions.73

James identifies many characteristics of Meredith’s prose: its rhetorical excess, its circumlocutions, its obscurity, as well as its withholding of knowledge, telling “the reader less of what the reader wants to know.” James gives a strong response to what critics have described as Meredith’s “confrontational” style: complaining of the “tortuosities” of Meredith’s novel, he suggests that the “threshing out” that Meredith’s statements require is unrewarding.

Meredith’s effortful style and his yoking of “feeling” to mental effort can, however, fruitfully be read within the context of recent scholarship on Victorian theories of the cognition of reading, specifically of the physiology of reading. Meredith’s approach to reading and style in the context of a mental economy of effort was not new. Meredith is, however, distinctive in aligning a deliberate intensification of effort in reading with a positive training of the mind. By contrast, Herbert Spencer made lack of effort in reading one of the central elements of his theory of style in his The Philosophy of Style (1852). Spencer presents a “readability theory” of style, arguing that “to so present ideas that they may be apprehended with the least possible mental effort, is the desideratum towards which most of the rules above quoted point.”74 The views of Spencer and Meredith on the role of effort in the process of reading and thus in good style are diametrically opposed. Yet both are grounded in a common notion of a psycho-physiological cultivation of the mind.

Meredith shares with Herbert Spencer the idea that continuing evolution meant the development of “more brain,” and he affirms Spencer’s belief in literature as a tool to cultivate the mind.75 Originally titled “The Force of Expression,” Spencer’s essay considers the underlying psychological principle of good style within a social context. Spencer conceived of society as a unified and developing organism made up of individuals whose united activities constitute its functions. The most efficient expenditure on the part of each individual then contributes to the better functioning of the whole. To fulfill its social function, literature, then, must strive for efficiency and conservation of mental effort. Within Spencer’s system, enervation has negative consequences, limiting rather than furthering the joint evolution and cultivation of the mind.76 Meredith, too, is concerned with the fatigue of readers but to him the problem is the enervating effect of a childhood diet of simple tales of plot and adventure.77 While sharing many of Spencer’s presuppositions—that reading should be considered within an economy of mental effort and that literature exists within a larger process of mental cultivation—Meredith draws the opposite conclusion about ideal style. Where Spencer holds that style in literature should aim to reduce cognitive effort, Meredith insists on the mental exercise of the reader as the central function of his “effortful” style.

A number of critics have recognized Meredith’s interest in mental training. Looking largely at thematic concerns, V. S. Pritchett pointed out, “Education is always in Meredith’s mind: how are we to be trained and for what?”78 Anna Maria Jones makes the leap to the novels themselves and considers Meredith in the context of the “cultivation” of the reader.79 She suggests that the “cultivation” of the reader “means the refinement of taste and careful husbandry of (human) resources,” in other words, “eugenics by way of aesthetics.”80 Meredith certainly seems to suggest that style or aesthetics can have a forceful effect on the development of the mind of the reader. Yet this process results not from the “husbandry” of mental effort but rather, as he never ceases to emphasize, through the expenditure of mental energy. Thinking is presented as tied to organs, as functioning like exercise. As Judith Wilt writes, “Meredith preached and practiced a sort of Muscular Readerhood that he did not hesitate to invite and create in his reader.”81

Meredith’s “effortful style” is therefore both deliberate and purposeful: his difficult and experimental style seeks new ways to display a mind that Victorian psychology has newly shown to be surprisingly opaque to itself. As we have seen, to Victorian psychologists the opacity of the mind was what demanded a reorientation away from questions of the content and nature of the mind to its dynamic functions. Culminating in the examination of the recalcitrant idea in One of Our Conquerors, Meredith’s novels show him to be centrally concerned with the problems of consciousness raised in part by the physiological psychologists: like much of the mental science of the period, Meredith is skeptical of the power of introspection, highlighting instead the many ways in which the mind is alien to itself. The difficult style developed in Beauchamp’s Career, especially the technique of narrating through indirection and frequent “non-recognitions,” reflects Meredith’s attempt to render these recent theories of cognition in the form and experience of narrative. Not to be understood as stylistic aberrations, Meredith’s difficult stylistics are intrinsic to his focus on the “brainstuff” and the “ideas of men” in the wake of the late nineteenth century’s reconceptualization of the nature of thinking.

Meredith’s aim is the “intensity of experience,” namely to keep both his characters and his readers in a state of “blood-heat.” Grounded in Victorian psychology, he emphasizes that intensity of experience, even physical sensation, is the result of cognitive effort. It is the dynamic experience of cognition that is vital. In keeping with the analogy to the runner, his narrative strategy uses the intensity of mental experience and the power of ideation to create powerful aesthetic and even physical effects, ultimately in service of cultivating the reader. Deliberately going against an established tradition of placing value on the ease of reading, his novels rely on the reader’s cognitive effort. Meredith’s novels thus capture a characteristic ambivalence of the Victorian rethinking of the nature of consciousness, which combines a recognition of the extent to which the mind may be outside conscious control and an emphasis on this very aspect of mind as offering the greatest potentiality for training. By deliberately intensifying cognitive effort, Meredith’s “breathless,” even “intoxicating” prose offers the possibility of training and strengthening the reader’s mind.