CHAPTER 2

More Schooling Alone Won't Necessarily Give an Education

The easiest thing for any successful social movement to do is to ask for more, especially more of the same. More of the same provides more to existing interests without demanding anything new. As public schooling has been one of the most universally successful social movements in history, it is tempting to try to solve the problem of too little learning by asking for more schooling.

The beauty of a universal schooling target is that more is an answer. Once a school has just been built here, replicating it—its building, equipment, and staffing—over there is the obvious next step. And, as we saw in chapter 1, this works: schooling has more than tripled in just sixty years.

Much advocacy is still focused on more schooling. Certainly the remaining unschooled children deserve additional resources and attention. Children who never enroll in any school today are mostly the world's triply disadvantaged—born to poor parents, in remote regions of poor countries, and into a socially disadvantaged or marginalized group.1 The drive to enroll the remaining poor and disadvantaged groups leads to targeted policy instruments, such as “conditional cash transfers”2 or targeted scholarships or innovations intended to ameliorate specific issues that limit enrollment.3 However, as we saw in the previous chapter, these instruments cannot be the organizing goal for the world's education systems, as currently those who never enroll in any school are only a tiny part of those who lack an adequate education. Advocates also focus on expanding the number of schooling years to be completed for the currently enrolled. With (near) universal primary school completion achieved, attainment goals expanded to universal elementary (lower primary plus upper primary grades) school completion or universal basic schooling (defined to include “junior secondary,” up to eighth, ninth, or tenth grade), and even to universal secondary school completion, up to twelve years. To illustrate that there is no end to the logic (or political viability) of just asking for more, advocates in rich countries now argue for universal tertiary schooling.

A universal education target would be easy to meet if it could be achieved the same way as universal schooling was: more, more, more, and eventually we get there. If this were true, then the same coalition of parental demand, informed advocacy, altruism, and political self-interest that was the “access axis”—the social and political movement that achieved universal schooling—could work again. Grade-completion-based schooling goals (like the Millennium Development Goal) could seamlessly morph into learning achievement goals, with no need for innovation, systemic change, disruption, or creative destruction. In other words, nothing hard would need to be done.

More schooling alone will get more kids an education—but leave millions of children still without an adequate education. This chapter shows that the expansion of schooling alone, without any improvement in the pace of learning, the steepness of the grade learning profile, can result in only very limited progress toward educating developing-country youth. When little learning happens per grade, completing more and more grades just won't help that much in achieving universal capabilities. For instance, at the average pace of progress observed on the Educational Initiatives (EI) questions in India from grades four to six to eight, it would take sixteen years of schooling to get 90 percent of students producing correct responses on tests of rudimentary reading and arithmetic skills.

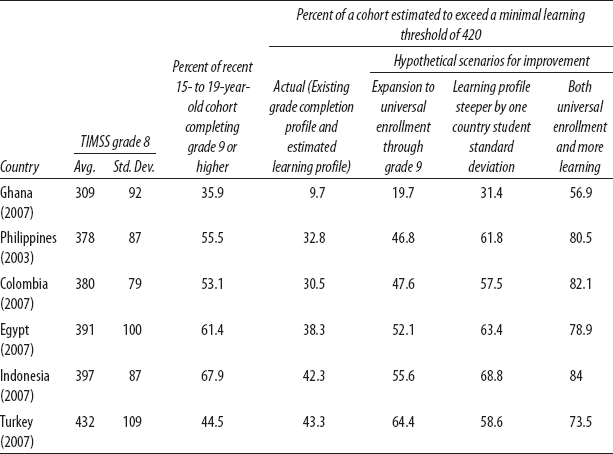

Flat learning profiles mean that expanding schooling is no guarantee of reaching, or even of making substantial progress toward, a learning goal. I estimate that in Ghana in 2007, only 9.7 percent of a cohort were above a minimal international threshold of mathematics capability (a TIMSS score of 420, which represents the global bottom 20 percent). Suppose that, at its current learning profile, Ghana achieved universal completion through grade nine. Only 19.7 percent would have been above that threshold. The accomplishment of universal basic education would have led to only one in ten more children meeting one reasonable learning goal. More generally, I show that at current learning profiles, even if the typical developing country achieved universal completion through grade nine, more than half of its students would not meet even a low international benchmark in learning. Unfortunately, while more schooling might be a necessary condition to achieving universal education, it is far from enough.

To disentangle the progress toward cohort learning goals—how many of a cohort of children leaving school age have adequate capabilities—from just learning achievement of those in school, we need to combine grade learning profiles, discussed in the previous chapter, with grade attainment profiles.

Grade Attainment Profiles

One way of summarizing the dynamics of schooling is to use information from household surveys about grade completion of a cohort to see, at least retrospectively, what fraction of an age-based cohort completed what grade (or higher). In a massive exercise, Deon Filmer at the World Bank compiles, on an ongoing basis, household survey data from over seventy countries (and for many countries, across multiple years). Using data on fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds, a cohort that is at (or near) basic education completion, Filmer calculates grade attainment profiles for these countries.4

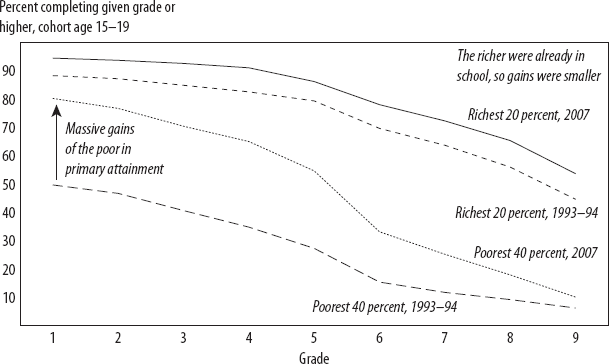

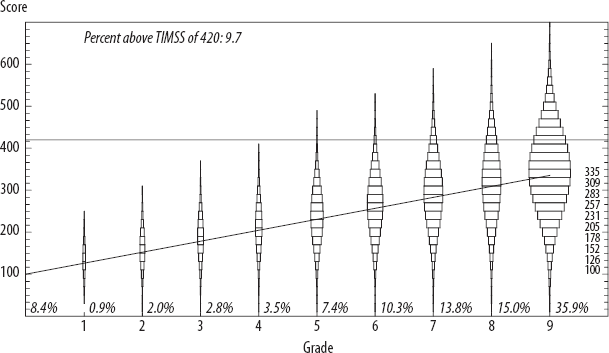

Figure 2-1. Grade completion profiles illustrate the difference between enrollment and retention as sources of schooling attainment deficits.

Source: Filmer (2010). Database at http://iresearch.worldbank.org/edattain/.

Grade attainment profiles have several advantages over enrollment rates. First, because they look at fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds, they give a picture of a cohort's attainment history—whether children enroll, how they progress across grades, and when they finish schooling. With grade attainment data, one can decompose the proximate contributions to lack of universal grade completion—for example, is it due to lack of enrollment or to attrition? In looking at Mali's fifteen- to nineteen-year-old cohort in 2001 in figure 2-1, for instance, it is clear that most of the deficit in universal completion can be attributed to those who never enrolled, as many did not complete even grade one, and these mostly never enrolled. This reveals an access problem.

Thankfully, as a result of efforts to expand schooling around the world, it is rare for children never to have enrolled in school. Ghana's cohort of fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds in 2008 shows the much more common pattern (see figure 2-1). Nearly all had participated in at least some formal schooling since 93 percent had completed at least grade one. But the combination of a low retention rate and a high dropout rate means that only 75 percent completed grade six, only half reached grade eight, and only 36 percent completed grade nine. Turkey's 2008 cohort is representative of a country with nearly universal completion through grade eight (as grade eight completion was made compulsory), followed by a sharp drop-off in the transition to grade nine: 86 percent made it through grade eight, whereas only 60 percent completed grade nine or higher. So even in an upper-middle-income country such as Turkey, many students complete their studies by grade eight or nine.

The second advantage of grade attainment profiles is that researchers can show grade completion differences by socioeconomic conditions. Grade attainment data are usually from household surveys, whereas enrollment data, which are usually from official sources, generally allow disaggregation only by gender or location.5 In developing countries, grade attainment curves have shifted up as more children have enrolled and persisted through the system longer, primarily through enrollment of poorer families (using a Filmer and Pritchett [2001] wealth index as a proxy for households’ socioeconomic condition). The changes in grade attainment profiles in Bangladesh illustrate the enrollment gains among the poorest. Figure 2-2 shows the grade completion profiles of cohorts in 1993–1994 versus 2007, thirteen years later, and compares the grade attainment profile of the richest 20 percent of households with that of the least wealthy 40 percent. Since the richer were already mostly in school, the bulk of the gains came from expanding the enrollment of the poorer parts of the population.

There is no question that continuing the momentum for universal primary education—to bring every child into school—is a necessary condition for learning. Moreover, it is inevitable that more and more countries will move to higher and higher levels of compulsory schooling, and hence join a widespread push for universal basic education of eight or ten years. However, the expansion of schooling in and of itself, without improvement in learning, will not adequately equip children for their future.

Figure 2-2. Expanding grade attainment has mainly been about including the poor (example of Bangladesh).

Source: Filmer (2010). Database at http://iresearch.worldbank.org/edattain/.

Learning Progress as a Combination of Grade Achievement and Learning Profiles

As in the previous chapter, I start with examples of specific questions and then move on to population averages for broad domains such as reading or mathematics. Any overall education goal will have a number of learning goals that reflect the capabilities of the cohorts around the age they leave school. Tracking a learning goal requires a cohort learning achievement profile, which encapsulates children's mastery over desired educational competencies at any given age. A cohort learning achievement profile combines grade attainment and grade learning profiles.

Flat Learning Profiles Mean Reaching Proficiency Takes Too Long

The Education Initiatives learning assessment discussed in chapter 1 features common questions asked in different grades in language and mathematics.6 This characteristic of the assessment tool allowed me to calculate changes in the percentage of students who are able to answer questions correctly per year of attendance, to derive a grade learning profile. As shown in table 2-1, the median pace per grade across different grade combinations is 5.7 percent, meaning that 5.7 percent of students who do not show mastery of the material on one year's testing are able to give correct answers after an entire additional year of instruction.

Table 2-1. Flat empirical learning profiles in India and Tanzania imply that even universal secondary school would not bring achievement in basic skills in reading and mathematics.

Sources: For India, Educational Initiatives (2010). For Tanzania, Uwezo (2011).

Note: I use median for EI because in one set of language questions, the increment is 1.4 per year, which substantially lowers the mean.

Taking the learning pace calculations a step further, I used the empirically observed profiles to ask the hypothetical question (supposing these learning profiles represented actual causal learning relationships): how many years would a cohort need to be in school before mastery became even near universal, such as 90 percent correct, or universal, 100 percent? If I make hard (and dubious) assumptions, the calculation is easy. Take the questions on language asked in grades four and six. These questions are simple enough that over half of students could answer them in grade four. By grade six, on average 64 percent could answer these same questions. This means a gain of about 6.4 percentage points per year. How many years are needed to get this cohort to 90 percent correct? It would take five additional years (rounded up to whole years of schooling), or eleven total years of schooling, to reach even 90 percent correct for basic language skills expected of fourth-graders.

Across all mathematics questions, the average is 14.3 years to reach 90 percent correct, or more years than is provided by universal primary, universal basic, or even the typical twelve years of secondary schooling. And keep in mind this is not to reach a target of sophisticated understanding and ability to do applications. It is just to reach very basic competencies in language, such as being able to complete sentences with a word, and in mathematics, such as doing simple arithmetic. In language overall (including questions asked beyond grade four), there is slower progress still: it would take 18.7 years of schooling to get 90 percent mastery of basic language capabilities.

As we saw in the previous chapter, India is not alone in slow learning progress. For Tanzania I estimated how long, given the existing learning profile, it would take to get universal proficiency. Here I used data from Uwezo Tanzania, an ASER-like basic skills test in Kiswahili, English, and mathematics. Uwezo reports the percentage of students meeting the low proficiency standard expected of grade two students (similar to ASER proficiency levels discussed in chapter 1) across all three subjects.7 By the end of grade seven in Tanzania, only 41 percent of students are proficient in the three fundamental subject areas. At that pace it would take thirteen years of schooling to get 90 percent of the students performing at the grade two level. At the current shallow grade learning profile, achieving universal secondary schooling would not even produce universal grade two education.

Disappointingly, the results in table 2-1 are optimistic. These are empirical profiles of enrolled students in those grades and not causal learning profiles, that is, how much more the same set of children would learn if they stayed in school. To the extent that children who do poorly on tests are more likely to drop out than other children, then empirical profiles of cross sections of students by grade will overstate the actual learning of individual students. As a simple example, suppose we tested a class of students, and half answered the question correctly and half did not. Suppose that none of the students who answered incorrectly progressed to the next grade (they either dropped out or repeated the year) while all of those answering correctly progressed. Suppose, again hypothetically, no one learns anything at all over the year. Then the average percentage of students answering correctly goes from 50 percent to 100 percent from one grade to the next purely mechanically, owing to selective lack of progression. In this case the empirical profile—which goes from 50 percent to 100 percent—does not represent a causal learning profile, which was, by assumption, completely flat.

Figure 2-3. Looking only at an empirical learning profile, and not taking into account dropout rates and repeating a year, can overstate learning progress per year.

Sources: Uwezo Tanzania (2010, Appendix A, table 1, and author's extrapolations); Filmer (2010) for grade attainment.

Note: Actual and extrapolated figures are identical for grades one through seven.

The differences between empirical and causal learning profiles can be illustrated with data from Uwezo Tanzania. Figure 2-3 combines the empirical learning profile, showing the fraction of students proficient in all three subjects by year of schooling compared with the 2010 grade attainment profile of a cohort aged fifteen to nineteen years. By the time students complete basic education in Tanzania (grade seven), only 41 percent are proficient in grade two basics. This figure jumps to 66.5 percent for those in the first year of secondary school (grade eight), which might lead one to think there are large learning gains between grades seven and eight. However, the grade attainment profile shows a significant dropout rate when students move from basic to secondary education. While 68 percent of the cohort complete grade seven, only 29 percent complete grade eight or higher, so nearly 40 percent of students drop out between grade seven and grade eight. If students with less proficiency drop out, the empirical learning profile will show a jump in proficiency across grades not because children learned but because those who knew less dropped out.

Cohort Learning Profiles: Combining Grade Completion and Learning Profiles

We are interested in more than the learning of those in school; we are interested in the education of all the children in a cohort. With the setup we have so far, we can mechanically decompose the empirical learning achievement of a cohort into (1) the grade completion profile, or the fraction of a cohort of a given age, arrayed by their highest level of schooling completed, and (2) the empirical learning achievement profile, or the level of competency or skill proficiency at each level of grade completion. These profiles are both featured in tables 2-2 and 2-3. By “mechanical” decomposition, I emphasize that no assertions are made about causality or about what could or could not be achieved with various policy instruments (that comes much later). Although there is a lot of arithmetic to this decomposition, it is just simple arithmetic.

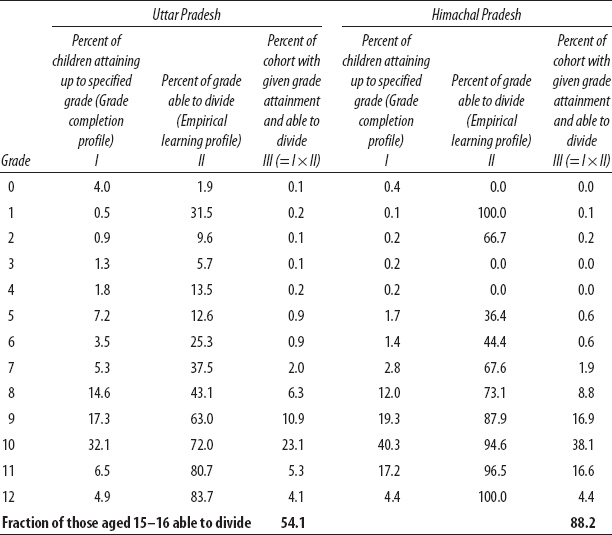

Table 2-2 illustrates the combination of grade completion and learning profiles using the raw all India ASER data from 2008 on ability to do division (ASER 2009).8 I compare the achievement of a fifteen- to sixteen-year-old cohort from a low-achieving (54 percent) Indian state, Uttar Pradesh, with that of a high-achieving (88 percent) state, Himachal Pradesh. How much of that gap is (mechanically) the result of their different grade attainment profiles and how much is (mechanically) an effect of the empirical learning profile?

Himachal Pradesh has higher grade attainment than Uttar Pradesh, with very few children in Himachal Pradesh completing only grade eight or below and 62 percent of fifteen- to sixteen-year-olds currently attaining grade ten or above. In Uttar Pradesh, in contrast, 56 percent of students attain less than ten years of schooling. The more striking difference between these two states is that at each level of grade attained, the ability to divide is strikingly higher in Himachal Pradesh. In grade ten in Himachal Pradesh, 94.6 percent of students can divide, whereas in Uttar Pradesh, even of the children who manage to make it to grade ten, only 74 percent can divide.

Table 2-2. Cohort learning profiles are the multiplicative product of grade attainment and learning achievement by grade, illustrated with two states in India.

Source: Author's calculations using ASER 2008 data (ASER 2009).

The proportion of a cohort that can divide at each grade attainment level is shown in table 2.2, in the third column under each state. This figure was calculated by taking the proportion of the cohort with each level of grade attainment (including none at all) times the fraction of those of each cohort at that grade attainment who can divide. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh, 7.2 percent of the fifteen- to sixteen-year-olds completed only up to grade five. Of these, only 12.6 percent could divide. So the fraction of the cohort who could divide and attained at most grade five is 0.072 × 0.126 = 0.009, or .9 percent of the cohort.

The average cohort learning achievement is just the sum of the third column for each state—the fraction who can divide. Cohort learning achievement profiles are very rare because one needs to have tested the entire cohort, not just those in school. So a school-based examination in grade ten in Uttar Pradesh would reveal that 72 percent of those who took the exam could divide, but this is only 32 percent of the entire cohort aged fifteen to sixteen years. The true cohort average has to include those 4 percent who never enrolled, almost none of whom can divide, and the 7.2 percent that dropped out after grade five, of whom only 12.6 percent can divide, and so forth. So only 54 percent of the cohort aged fifteen to sixteen years can do simple division, much lower than the grade ten average of 72 percent.

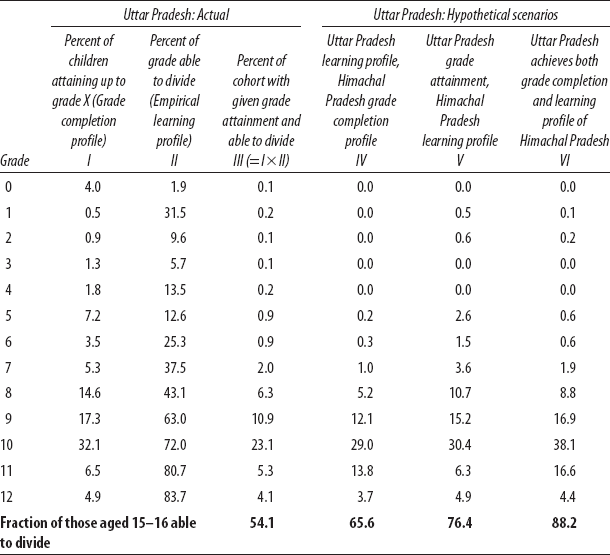

With the grade completion and learning profiles for these two states, we can, in table 2-3, hypothesize about how Uttar Pradesh could increase the proportion of children able to do division. What if more children in Uttar Pradesh simply stayed in school longer? For example, what if Uttar Pradesh had Himachal Pradesh's level of grade attainment but at Uttar Pradesh's observed learning profile? That massive increase in schooling in Uttar Pradesh would improve the cohort mastery of division from 54 percent to only 66 percent (column IV of table 2-3).

Conversely, suppose that at exactly its same grade attainment, Uttar Pradesh were able to achieve the same empirical grade learning profile as Himachal Pradesh, so that children learned more per year. Then the cohort mastery of division would increase from 54 percent to 76 percent. This is almost double the gain in learning from increasing enrollments. Obviously, if Uttar Pradesh did both, then it could achieve the same cohort mastery (88 percent) as Himachal Pradesh. But Uttar Pradesh could be two-thirds of its way to Himachal Pradesh's cohort performance by improving the learning of those in school, while they get only one-third of the way there by expanding enrollment.

Expanding Enrollment Does Little to Meet Education Goals

As we move from a single concept (such as doing division) to a broader assessment of skills in a domain (such as mathematics, reading, science, or history), the analysis becomes more complicated, but the same arithmetic applies, and the findings are similar. The point is obvious, but worth stressing. If a country has a shallow learning profile, this means students make little progress in learning per year of schooling, and hence expanding years of schooling does not move them very far toward meeting a learning goal. It can take a lifetime to climb a mountain if the slope is too gentle.

Table 2-3. Expanding Uttar Pradesh's grade completion to that of Himachal Pradesh while keeping the same learning per grade increases cohort mastery only modestly.

Source: Author's calculations, based on ASER 2008 data (ASER 2009).

Analysis using broad assessments gets more complicated for two reasons, one easy and one hard. The easy part is that broad assessments of a learning domain produce an entire distribution of results across students, some scoring high, some low, rather than just one yes/no for each student. I addressed this issue by moving from a spectrum of performance across students to the equivalent of a simple yes/no by using a threshold score in the distribution of student performance. As I did with PISA and TIMSS data in chapter 1, I chose a level of mastery—say, a score of 400 on the PISA exam or 420 on the TIMSS—and examined what fraction of students were above that level.

The hard part is that almost no one tests cohorts; rather, enrolled students are tested. Most internationally comparable examinations set the age or grade of the assessment so that nearly all students in wealthy countries are still in school, and for wealthy countries, the discrepancy between enrolled and actual cohorts is negligible. But this is not true of poorer countries. To get from an estimate of the performance of enrolled students to an estimate of cohort performance, we need the distribution of the test results for the out-of-school children—but these children are not actually tested. This is a difficult problem because we need something we don't have. To fill in the missing data, I made some assumptions that allowed me to work from the data I do have to the information I wanted, and imputed how the distributions of performance by grade would evolve.

Learning Effects of Increasing Enrollment and Attainment versus Steepening Learning Profiles: Some International Comparisons

I started by using TIMSS data to calculate how much countries can gain from enrollment expansion. Using TIMSS data is the easiest because the TIMSS sampling frame is grade-based, and the assessment tests all children in grade eight. To impute the distributions in other grades, the assumption I made for TIMSS was that the learning profile is linear and takes students from an assumed minimum of 100 to their observed score in grade eight, in equal increments.9 For instance, the 2003 TIMSS score for the Philippines is 378, so I assumed that the total progress was 378 − 100 = 278 over seven years of schooling; thus the increment of learning per year is 39.7 (278/7). My second assumption was that the distribution of the scores is exactly Gaussian normal, and my third assumption was that the dispersion of the distribution of performance, measured by its coefficient of variation, stays constant across grades.

Table 2-4. Progress in universal education requires both expanding schooling and raising the learning profile.

Source: Author's calculations described in the text, using data from TIMSS (2003 and 2007 surveys) and grade attainment data from Filmer (2010).

Using these three assumptions, data from TIMSS 2003 and 2006 (TIMSS 2003, 2007) and the grade attainment data from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (Filmer 2010), I calculated what fraction of a cohort was above a threshold of 420 in mathematics, a potential learning goal in mathematics for TIMSS (for an explanation of why I chose 420, see chapter 1). In table 2-4 I show TIMSS means and student standard deviations, the percentage of a cohort attaining grade nine or higher, and the fraction of the cohort testing above 420, for six developing countries with recent TIMSS data.

I am comparing grade nine achievement for two reasons. First, grade nine is typically the highest grade proposed as part of “basic” education (primary plus junior secondary), while grades above nine are typically considered “secondary” schooling—although of course, in many countries grade seven or eight ends basic schooling and grade nine is already part of the secondary cycle. Second, on a more practical level, for technical reasons I can only get grade attainment profiles of cohorts only through grade nine,10 so it is what it is.

What if these six countries were somehow to achieve universal completion of schooling through grade nine at exactly their existing learning profile? How many more students would reach a learning goal? This actually has an easy answer: it is just the fraction who would be above 420 at grade nine. In a country like Ghana, with a very shallow learning profile, reaching universal grade nine attainment does not increase learning by much. The fraction above 420 (as one possible illustrative learning goal) increases only from 9.7 to 19.7 percent of children. Even with universal completion of grade nine (basic schooling), 80 percent of children would not meet even a minimally defined learning goal in mathematics competency.

Naturally, countries with higher initial performance get more out of expanding grade nine attainment. But in many of these countries, there are not that many children not already making it to grade nine, so the potential gains from enrollment alone are limited. For example, in Colombia, by just expanding grade nine attainment to universal, the fraction of children meeting the 420 learning threshold rises from 30 percent to 48 percent, which is a substantial gain: almost one in five children move above the 420 threshold. But still, half of children are below a learning goal at grade nine. Egypt and Indonesia move toward a universal learning goal with expanded enrollment, but only to barely above half of students above the learning goal at universal grade completion. Only in already quite high-performance countries such as Turkey would enrollment expansion alone get the country significantly more than halfway to a learning goal.

I also ask a different hypothetical question: what if these countries did nothing to expand enrollment but somehow managed to raise their learning achievement by a full student standard deviation? How to do that is a big question, one that will occupy the rest of the book. But suppose that countries were able to steepen their learning profiles. In every country (excepting Turkey), raising learning achievement in this thought experiment produces much bigger learning gains than achieving universal completion by expanding enrollments. The fraction meeting the TIMSS score of 420 learning goal in Ghana goes from 9.7 percent to 31 percent—twice the gain from enrollment expansion. In Colombia, the learning goal attainment goes from 30 percent to 57 percent, and in the Philippines from 32 to 61 percent.

Not surprisingly, the combination of higher grade attainment and raising the learning profile is most effective in helping students meet a learning goal.

The decomposition of the cohort achievement into cohort grade completion and a learning profile is easy to see graphically. That is, the graphs are necessarily complicated as they have to collapse three dimensions (grade, score, and distribution across students) into a two-dimensional diagram. But once you get used to the graph, the point about the relative contribution getting to a higher level by either walking farther out a flat ramp or walking the same distance up a steeper ramp is easy to see.

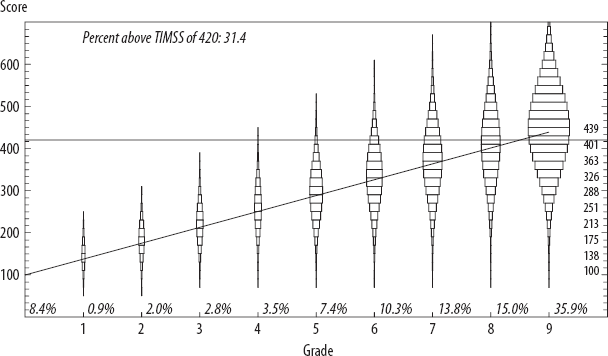

I use Ghana's TIMSS results from 2007 to illustrate the current reality and the two scenarios. Figure 2-4a shows the reality. The “normal” distribution11 areas (which look like onions or Christmas ornaments) at each grade level show the distribution of competence in mathematics for students at that grade level. This is based on the TIMSS mean of 309 and standard deviation of 92 (shown in table 2-4) for the performance of grade eight students. The distributions for all other grades are extrapolated using the assumptions (discussed above) of (1) a linear learning profile from a minimum of 100 in grade one to the grade eight score of 309, (2) a constant coefficient of variation across grades, and (3) a normal distribution of scores in each grade.

The total size of the “normal” shape at each grade is the proportion of the fifteen- to sixteen-year-old cohort completing that grade level or higher. For instance, since 13.8 percent of the cohort has grade seven as the highest grade completed, the area of the onion shape at grade seven has 13.8 percent coverage of the total area in all of the figures.

Figure 2-4a. Only 9.7 percent of a Ghanaian cohort aged 15–19 years is above a minimum learning threshold in mathematics.

Source: Author's calculations, based on TIMSS 2007 survey data and Filmer (2010) data.

Note: The size of the distribution shape for each grade corresponds to the proportion of 15- to 19-year-olds completing the specified grade or higher. The proportion is also indicated numerically above each grade. Area of distribution shapes above 420 represents the total population above 420, which in this case is 9.7 percent.

The beauty of this graph (again, I realize it is not beautiful at first, but it will grow on you) is twofold. First, the percentage of students meeting a learning goal is just the fraction of the area of all the shapes above the hypothetical learning goal. In 2007, only 9.7 percent of the fifteen- to sixteen-year-old cohort was above 420—which is the cumulative area above the line at 420.

The second beauty of the graph is that it can easily illustrate two basic ways of increasing the number of students who meet a learning goal. The first way is by increasing grade attainment, which is visually pushing the area of the curves representing grade completion to the right along the same learning profile: more and more kids get to higher and higher grades, but their scores are increasing at the same learning profile pace. Figure 2-4b shows the limit of this—all students have completed grade nine, so all 100 percent of the onion-shaped “normal” area is in grade nine. In this case, the percentage meeting the learning goal is simple: it is just the proportion of the area of the grade nine achievement distribution above the stipulated learning goal. But since the average at grade nine is only 335, only 19.7 percent of a cohort is above 420 even with universal basic completion.

Figure 2-4b. Achieving universal grade completion in Ghana increases the proportion of students above a minimum mathematics learning threshold only from 9.7 percent to 19.7 percent.

Source: Author's calculations, based on TIMSS 2007 survey data and Filmer (2010) data.

The second way of increasing the number of students who meet a learning goal is by increasing learning per grade, or steepening the profile, so that a child with the same attainment demonstrates higher achievement. Visually, this is raising how fast the onion bulbs shift up per year. What if Ghana found a way to steepen its learning profile by a student standard deviation (which, for Ghana, is 91 points)? The average child who made it to grade nine would have a score of 439 (near Turkey's current level). This means that now 31 percent of a cohort would be getting minimally adequate learning achievement. The other 69 percent still would not be above that level, but the gain from a steeper learning profile is twice as big as that achieved through reaching universal enrollment alone.

And what if Ghana managed to reach universal grade nine attainment and increased learning per grade? Then the fraction of children at age fifteen with some modest command of mathematics (above 420) would increase from less than 10 percent to more than 50 percent.

Figure 2-4c. Steepening the learning profile in Ghana increases the proportion of students above a minimum mathematics learning threshold from 9.7 percent to 31.4 percent, double the increase in learning from universal grade 9 enrollment.

Source: Author's calculations, based on TIMSS 2007 survey data and Filmer (2010) data.

Figure 2-5 shows four graphs together for the Philippines constructed using TIMSS 2007 survey data—base case, universal grade completion, a steeper learning profile, and both grade completion and a steeper learning profile. These show the gains from enrollment expansion and learning profile improvement separately and the gain from both. Enrollment alone gets to less than half, steepening the learning profile alone gets to around 60 percent, while with both, 80 percent are reaching the learning goal.

These illustrations using mathematics scores are just that—illustrations. The point is that reaching a high level of capability means walking very far if the walking path is nearly flat. This is true of any educational objective, from reading to creativity to tolerance to critical thinking.

These illustrations are not to be mistaken for a proposal to adopt “above 420 on TIMSS in mathematics” as a learning goal. Rather, I am making two simple points. First, the objective of school isn't school. Schooling has to be about goals measured in terms of achieved capabilities. What exactly these desired capabilities are is up to the society (and parents and students) to decide, and there will be many; they could be reading, mathematics, citizenship, creativity, the ability to learn, critical thinking, appreciation of poetry, and tolerance of others, but schooling has to be something other than just sitting in school. Second, if the relationship between the school learning objectives and time in school is weak, as in Ghana, then expanding time in school doesn't help with the education goal that much. My use of the mathematics scores from TIMSS is not meant to argue for a “back to basics” approach to education in which math has priority, or to argue that TIMSS's approach to assessment is better or worse than any other, or even that “standardized testing” is the best way to assess student mastery. But schooling is the means, while education—however defined—is the end.

Figure 2-5. Steepening the learning profile and increasing enrollment in the Philippines is the optimal strategy to maximize learning: it increases the proportion of students above a minimum mathematics learning threshold from 32.8 percent to 80.5 percent.

Source: Author's calculations, based on TIMSS 2007 survey data and Filmer (2010) data.

I can do similar calculations for other approaches to assessment with other subjects, such as with the PISA 2009 and 2009+ round,12 and get the same basic results. As discussed in chapter 1, PISA is an age-based (not grade-based) test of enrolled students (not a cohort), so results show what fraction of the enrolled cohort is below any given standard, rather than the fraction of the total cohort that is below the standard. PISA data can be used to answer the question, if all students (including those who did not enroll or who dropped out) had the same distribution of performance of the enrolled students, what fraction would still be below a learning goal?

Figure 2-6 shows the fraction of enrolled fifteen-year-old students below level 2 learning in the most recent PISA results.13 (This is the average fraction across reading, mathematics, and science.) Ten of the nineteen countries or states have half or more fifteen-year-old students—even of those still in school—with below level 2 proficiency.14 Hence, even if all students stayed in school to age fifteen (at which age students are typically in grade eight, nine, or ten), at the same distribution of learning, less than half would be at a minimally adequate level of learning.

In using internationally comparable standardized assessments such as PISA and TIMSS, I am not arguing for a particular learning goal or standard based on the existing global comparisons. Exactly the same calculations of learning profiles that lead to learning goals could be done with national or regional standards. For instance, the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) does reading and mathematics assessments of in-school grade six children in fourteen African countries. SACMEQ has devised its own scale and levels: eight levels for reading (from “pre-reading” to “critical reading,” with level 3 as “basic reading”) and eight for mathematics (from “pre-numeracy” to “abstract problem solving,” with level 3 as “basic numeracy”).15

Figure 2-6. Most students enrolled at age 15 in most developing countries are far from achieving adequate learning.

Source: PISA (2009, tables I.2.1, I.3.1, and I.3.4).

Note: Definition of “developing” for the developing country average (Dev Av) excludes all former Soviet or Eastern bloc countries, the high-performing East Asian countries (such as Korea and Singapore), wealthy Persian Gulf countries (such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates), and the estimates for Shanghai, China. Developing country average is unweighted. Country codes are UN standard codes.

The results of the 2007 round of assessments (SACMEQ 2010), presented in table 2-5, show that in mathematics, three quarters or more of sixth-graders do not reach above level 3 in Malawi, Zambia, Lesotho, Uganda, Namibia, or Mozambique. Nearly four in ten do not reach above level 3 in every country but Mauritius.16

What if SACMEQ participants expanded enrollment and grade attainment? These southern and East African countries have relatively high grade completion rates (compared to West Africa or the Sahel), so there is not much scope for gains in cohort learning goals from expansions in primary school completion. If one set a learning goal for primary schooling as mastering even above level 3 competencies, and even if these countries attained universal grade six enrollment, the majority of students would still fall short of a learning goal in mathematics; and a large plurality would fall short in reading.

For example, in South Africa, already over 90 percent of youth complete grade six or more, so reaching universal grade six schooling, even if it raised the non-completers to the level of capability of those in grade six, would, under the most optimistic assumptions, add only 3.2 percentage points to the fraction of the cohort with adequate skills. That is, suppose that all children who did not complete grade six did not attain above level 3 in mathematics. Then the cohort average would be 92.4 percent grade six completers times 30.8 percent of grade six completers at level 4 or above, plus 7.6 percent non-completers times 0 percent at level 4 or above, which equals 28.4 percent at level 4 or above. At a 100 percent completion rate, this would be equal to those who are now in grade 6, which is 30.8 percent. So reaching universal enrollment would add, at best, two percentage points to the fraction reaching an “above level 3 competence” learning goal. In contrast, in Kenya, 61.7 percent of enrolled students are at a level that is 30 percentage points ahead. Put differently, the difference between the percentage of students at mathematics level 3 or below is more than 30 percentage points higher in Kenya than in South Africa. So the gain to South African learning from having Kenya's learning profile is ten times as big as the predicted gain from expanding enrollment (a 29.7-percentage-point increase in the percent of students at acceptable mathematics competency) versus pushing for universal primary school completion (a 2.3-percentage-point increase in the percent of students at mathematics level 4 or above).

Table 2-5. Achieving universal primary schooling (grade 6) would not bring even half of students in most countries to regionally adequate levels in reading or mathematics.

Source: SACMEQ (2010) for learning levels, Filmer (2010) for cohort grade attainment.

a. Percent of grade 8 students below a low benchmark (400) on TIMSS 2007 Mathematics: 68 percent, versus 56.4 percent at or below SACMEQ level 3.

b. Percent of students age 15 below level 2 in PISA 2009+: Reading, 36.2 percent; Mathematics, 46.8 percent versus 21.1 percent; and 26.7 percent at or below level 3 in SACMEQ.

c. Assuming that zero percent of children completing less than grade 6 are at level 4.

n.a. = Not available.

Why Setting Education Objectives and Tracking Progress in Meeting Them Is Essential (and Why Specific Metrics Are Less So)

It is important to note that I have no particular stake in the particular calculations I have just shown. I don't care whether PISA or TIMSS or SACMEQ or any other particular international testing metric is used. Nor am I advocating for the importance of mathematics or reading or science skills over any other skill set that schooling sets out to achieve. I use quantitative measures of standard skills because these are the data I have, not because I am pushing for achievement on these measures rather than on any other set of educational outcomes as the goals of education, such as the ability to work in groups, communicate effectively, or think critically. There are many who oppose “testing” because they feel that putting “high stakes” on certain dimensions of education goals will detract from other dimensions of education. But there is nothing intrinsic in a cohort learning approach that specifies which dimensions of competencies/skills/abilities are to be assessed, or how those could be assessed. And, as I will show, the “no assessment” option has risks of its own. If I had data for those outcomes, I would use them too, and I strongly suspect, for example, that “critical thinking” data would produce similar results. Unlike the debates in wealthy countries about the relative emphasis on different educational outcomes for students mostly already with mastery of basics, I highly doubt (but for lack of any relevant data cannot conclusively prove) that students in India who cannot read or count nevertheless somehow manage to excel at “critical thinking” or “creativity.”

Data on reading, mathematics, and science are available because these domains are universally regarded as relevant in every education system. That is, every education system claims it teaches children reading and mathematics and science. If educational systems want to encourage students’ ability to think creatively, analyze arguments critically, work with others from diverse backgrounds effectively, or any other new basic skill, there is no reason in principle these skills and domains could not be assessed and included in a country's learning goals.

I am not arguing for an international standard versus national or even regional standards, so I am not going to defend 420 versus 440 versus 380 versus any other level, nor am I arguing for any particular approach to assessment, such as the “curricular mastery” versus “life skills and applications” approach.

I am advocating for education systems to measure and work to achieve their education goals—whatever they are. And calculations like cohort learning profiles are essential to understanding what you are achieving. The basic finding I am highlighting with a variety of measures (such as ability to perform simple division versus mathematics versus reading) and at a variety of levels of mastery (using country, regional, international benchmarks) is robust: (1) the education objectives of schooling are not being reached at anything like the pace they need to for children to be equipped for their futures and (2) expanding years of schooling at the current pace of learning just won't help that much. This basic finding emerges no matter which subject matter or skill set is tested, no matter which method is employed, because schooling is already high and learning is still low. More schooling—which is the easiest thing for the existing educational organizations and the education movement itself to promote—will not solve the education problem.

The False Dichotomy of “Quantity” versus “Quality”

School is the fiercest thing you can come up against.

Factories ain't no cinch, but schools is worst.

GIRL WORKING IN A FACTORY IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY CHICAGO (TYACK 1974)

These illustrations of the relative impact of enrollment and attainment versus learning should not lead to simplistic interpretations or premature policy conclusions. A focus on cohort learning goals can restore the true purpose of education systems and obviate the false debate over “quantity” versus “quality.” That is, many have legitimately opposed the view that to maintain quality for students already enrolled, the pace of enrollment expansion needs to be limited. However, in a cohort-based assessment of learning distributions, both quantity (moving along the learning profile by increasing attainment) and quality (raising the learning profile) are essential. With measures of the entire distribution of cohort learning, targets can be based on averages, inequalities, or minimal achievements to reflect any array of education goals.17 Cohort-based measures of learning do not intrinsically favor quality over quantity, as both are fundamental to achieving universal learning goals.

Moreover, no one could sensibly argue for quantity if in fact learning profiles in all relevant domains, including cognitive and noncognitive skills, were truly flat. Some justify low performance on cognitive skills assessments by saying, “Well, it is okay if students are not learning much math or reading; the important thing is that they are in school.” But no one wants kids to sit in a building called a school just because it is a building called a school. Some argue that through the experience of school, children will acquire other traits societies or nation-states desire, such as a sense of appropriate behavior (for example, obedience to authority), social solidarity, national pride, religious faith, or admiration of Mao or Atatürk, even if they don't learn anything else. But what a cruel trick that is to play on children! That is, if year after year, schools pretend to teach math or reading or science while not really caring whether kids learn math or reading or science as these subjects are really only a pretext to achieve other goals, well, forcing that on kids is just plain mean.

When It Is (Nearly) All Dropout

In this chapter, I have developed scenarios using mechanical calculations to show the consequences of expanding enrollment without improving learning quality. Certainly when enrollment is limited by physical access or ability to pay, policies can expand enrollments even at constant quality. However, the massive success of expanding schooling facilities implies that pure access-based deficits in grade completion are mostly small. The question is why children drop out, and what can be done about it. If children drop out of school because of the low quality of the instruction, then the scenarios presented above for the scope for improvements in learning through enrollment expansion, even as small as they are, overstate the potential for quantity expansion, as you cannot get it without quality.

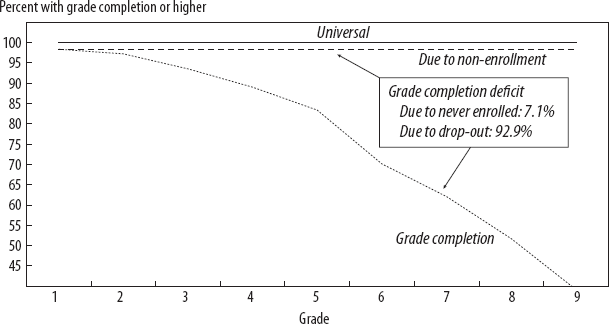

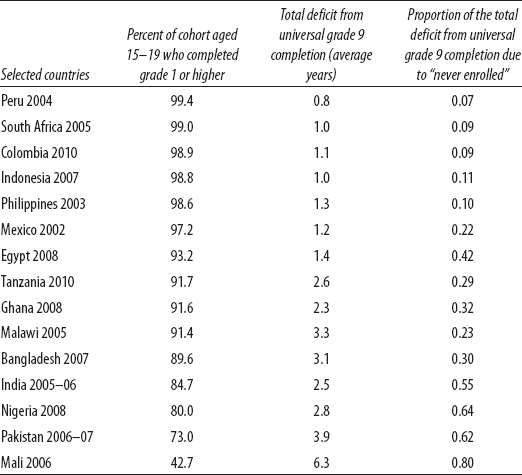

As I mentioned in the beginning of this chapter, and as shown in figure 2-1, attainment deficits around the world are increasingly the result of students dropping out, rather than nonenrollment. Countries like Mali, where less than 50 percent of children ever enroll or complete grade one, are thankfully a minority. Colombia is more representative of the majority. The grade completion profile of a fifteen- to nineteen-year-old female cohort in 1995 is shown in figure 2-7.18 Nearly every child started school, but only 40 percent completed grade nine or higher. One can calculate the total deficit between years of schooling and grade nine completion. For example, those with no schooling would need nine years, those who dropped out in grade five would need four more years, and so on.19 The obvious point is that in a country like Colombia, the “never enrollment” problem is small, so the completion deficit due to those who never enrolled is also small (even though some children completely lack schooling). Thus, strategies to meet attainment goals should be focused on keeping kids in school and progressing through grades.

Figure 2-7. Most of the attainment problem in Colombia is due to high dropout rates, not low enrollment.

Source: Author's calculations, based on Filmer (2010) data.

Looking at a handful of other countries, in table 2-6 I show the proportion of the total deviation from grade nine completion due to “never enrollment.”20 There is little remaining dropout in many countries where few children are meeting basic levels of proficiency. In middle-income countries such as Egypt, Indonesia, the Philippines, or South Africa, any reasonable calculation of learning goals would show that half or more of the cohort reaches the end of basic education ill-equipped for a future in the workforce or citizenry. But in these countries almost every child enrolls. For instance, in Peru, the PISA results show that two-thirds of a recent cohort—those in school—are below low international benchmarks in reading, mathematics, and science. And yet few children never enroll—99.4 percent of the cohort aged fifteen to nineteen years in 2004 had completed at least grade one. This means that the issue of access is nearly irrelevant in Peru's deficit from any learning goal.

Table 2-6. In very few countries is much of the deficit in universal grade 9 completion attributable to children never having enrolled in school.

Source: Author's calculations, based on Filmer (2010) data.

Even in relatively poor countries, such as Ghana, Malawi, or Tanzania, the proportion of the total grade completion deficit is less than a third. This means that two-thirds of the grade attainment deficit is due to children who attended school but dropped out before reaching grade nine. Of course, there are some places where access is still a major issue, as I illustrated above with Mali (see figure 2-1), but ever enrollment is not a major challenge to universal grade nine attainment in most countries.

The scope for expansion of schooling through expansion of physical access to schooling is nearing an end. Using regressions that predict child enrollment, Filmer (2007) estimated the relationship between child enrollment and distance to school in twenty-one low-income countries and calculated that even if an expansion in access meant the average distance to a primary school was zero, the typical country increase in enrollment would be less than one percentage point. This is not to say that expanding access isn't important in some places. Filmer estimated that in Mali, it would have gone up ten percentage points. There is no question that building schools expands enrollment when there has been a lack of physical access. But as a result of the tremendous success of the schooling agenda, those places are fewer and fewer. Recent rigorous evaluations have found that school construction, even when combined with school improvements, has mixed impacts. For instance, an evaluation of the construction of improved schools in Burkina Faso found a substantial impact on enrollments, attendance, and learning (Levy et al. 2009), but in Niger, a country with low enrollments, a program of school construction and improvement had very limited impact on enrollment (only 4.3 percentage points) and no discernible impact on attendance or child learning.

Nearly all of the expansion in schooling will be convincing children to stay in school (and their parents to keep them there). Do children stay in school when not learning?

Why Do Children Drop Out?

If you can follow what is going on, and perhaps even excel in the classroom, then school is fun. You get to do something you are good at, make progress, and get repeated positive feedback (and avoid other tasks, such as gathering firewood or tending goats). People for whom school is fun tend to do more of it, and many become researchers and professors. These people then write books about, among other things, education. The irony is that these people are the least likely to really “get” the retention problem. After all, how likely is it that a person who did ten more years of schooling than legally required will have good intuition for why others quit school? People adept at school find intrinsic enjoyment in it, in addition to its instrumental value, and thus have a hard time understanding why not everyone wants to go to more school.

In the perfectly legitimate interest of promoting schooling, advocates often lose sight of what a miserable and alienating experience school can be. Particularly for adept and intellectually brilliant researchers who attended excellent schools, it takes a tremendous leap of empathy from their own conditions to those of children in Uttar Pradesh. Imagine you are one of the half of the fifth-grade class that still cannot read. The teacher's writing on the board, textbooks, and workbook exercises on any subject mean nothing to you. You realize you are falling further and further behind but do not know what to do about it, nor does anyone seem to care. Worse, a recent survey found that 29 percent of children in India—and a much higher rate among the poor—were “beaten or pinched” in school in the immediate past month (Desai et al. 2008). A study examining “child-friendly” teacher classroom behavior in five states in India found that in less than a third of classrooms were students observed asking teachers questions; and in only about one in five classrooms was the teacher ever observed to “smile/laugh/joke” with any student (Bhattacharjea, Wadhwa, and Banerji 2011)—and if you are a low-performing student, perhaps with you least of all.

Being unable to follow the lessons, getting pinched or beaten, and not learning make school unpleasant at best. The Educational Initiatives study (2010) compared the language and math scores of students according to characteristics about themselves, the schools they attended, and their teachers. The simple cross-tabulations reveal that the single biggest factor associated with test scores was whether students found school “boring and not useful” (average test score 40.6) or “fun and useful” (average test score 56.4). Whether this is because bored children do not learn, or because if a child is behind and not learning, school is a boring place, one cannot say, but these definitely go together.

But what are the reasons for dropping out? Education studies are dominated by analysis of factors that “pull” children out of school—poverty, the need to work, or marriage. But this is perhaps because researchers like school and assume that others do too. Pull factors are indeed important. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in the 1990s asked girls why they dropped out of school. As shown in table 2-7, family reasons (about a quarter) and economic reasons (about another quarter) were, naturally, significant factors.

But “push” factors also influenced girls’ drop-out decisions. In Colombia's 1995 DHS survey, the most frequent reason given for why girls dropped out of school, noted by 31 percent, was “did not like school.” Simple arithmetic shows that not liking school is an enormously larger problem for expanding grade completion than is access. (Since I showed in figure 2-6 that 93 percent of the attainment deficit in Colombia is due to dropout and 7 percent is due to nonenrollment, 31 percent of the 93 percent of the attainment deficit due to dropout is bigger than 7 percent of the attainment deficit due to “never enrolled.”) It is impossible to know more about why they did not like school, but it is conceivable that the frustration from low learning progression may play a big role.

Table 2-7. Worldwide, about half of girls report leaving school for reasons that pull them out, such as poverty or family, but many report leaving school because they just do not like it or they did not pass exams.

Source: Author's calculations, using DHS Statcompiler (http://statcompiler.com/).

The simple point is this: it is hard to make children who are not learning, and who know they are not learning, stay in school. The calculations above about how much could be done for learning with enrollment expansion alone implicitly assume that achieving universal grade completion is possible with unchanged learning. But this assumption is dubious. Conversely, almost certainly improving learning will keep more kids in school longer.

Keeping Kids in School—and Learning

Much of the recent education research has been devoted to two initiatives largely focused on expanding enrollments: eliminating charges for schools and conditional cash transfer programs (which started in Latin America and spread). Both these initiatives have been successful in putting more kids in schools, but neither has been shown to improve the learning profile (Fiszbein and Schady 2009), and whether either one increases learning at all has found mixed results.

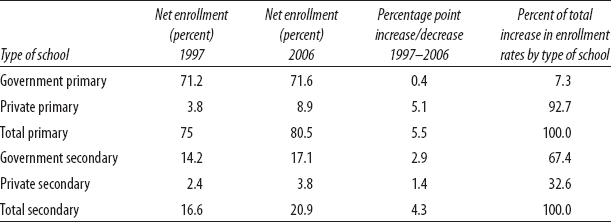

Table 2-8. Abolishing government primary school fees in Kenya in 2003 was associated with increased enrollment almost exclusively in private schools—which did not charge fees.

Source: Adapted from Bold et al. (2011, table 1).

In January 2003, Kenya adopted a free primary education policy and abolished all fees in government-controlled primary schools, with the goal of increasing enrollments. Enrollments increased from 1997 to 2006, but nearly all of the net increase was in private schools, which did not eliminate fees. Moreover, the increase in the net enrollment rate in government primary schools, which eliminated user fees, was 0.4 percentage points, compared to 2.9 percentage points in government secondary schools, which did not eliminate user fees. One reading of this experience (Bold et al. 2011) is that the government's attempt to make the schools cheaper in the interest of expanding enrollment and attainment caused parents to think that quality had gone down (as many of the fees were locally controlled and used for school inputs). This led to weak increased demand for government-controlled schools, while the relative price in money terms fell; and enrollment in government schools fell precipitously for the children of higher-educated parents. Strikingly, the proportion of additional enrollment that went to government schooling was much higher for the secondary sector (67 percent) that did not eliminate fees than for the primary sector that did (only 7.3 percent) (table 2-8).

Malawi adopted free public education in 1994. The fraction of a fifteen- to nineteen-year-old cohort with no schooling fell from 26.4 percent in 1992 to 8.6 percent in 2005. During this same time period, the fraction of the cohort finishing grade six or above rose from 31 percent to 57.2 percent—a huge improvement. However, the SACMEQ 2007 results show that only 26.7 percent of those in grade six could read with even minimum proficiency, and only 8.6 percent had minimal numeracy skills (see table 2-6). If these additional 26.7 percent of grade six completers from free public education had average 2007 learning levels (which is an optimistic assumption), only an additional 7 percent of children reached a reading goal and only 2.2 percent reached a numeracy goal.21

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) induce children to go to school by conditioning their household's receipt of targeted transfers on enrollment or attendance. This has become a popular policy tool, shown to increase attainment in a large-scale randomized experiment in Mexico (Behrman, Sengupta, and Todd 2005), and has spread from its origins in Mexico (where it was formerly known as PROGRESA and is now known as Oportunidades) and Brazil to more than thirty other countries. However, if the child dropped out because he or she was not learning in school, there is nothing about the program that helps that. Intriguingly, the initial evaluation of PROGRESA, which many cite in claiming that CCTs “work,” found no impact on learning at all (Behrman, Sengupta, and Todd 2005).22 Of course, if CCTs do nothing to raise the learning profile and the children who dropped out of school did so because they were not learning, then the increment in learning from a program that financially induces them to go back to those same schools so that their family might qualify for cash from the government could, unsurprisingly, be even less than that of the typical enrolled child. CCTs are a wonderful mechanism to transfer purchasing power to poor households, but at best, we should expect only modest impacts on learning.

The recent results of the centralized secondary school leaving examination in Tanzania illustrate a possible scenario. After implementation of a variety of policies for expanding schooling, the number of students sitting for the examination expanded massively from 2008 to 2011. Almost 200,000 more students took the examination in 2011 than in 2008. This rapid expansion might have kept weaker students in school all the way to schooling completion, so perhaps the proportion passing the examination would fall but the total number would go up. But that is not what happened. In many subjects (including compulsory subjects such as Kiswahili) the absolute number passing the examination at a grade C level or higher fell in absolute terms. In history, 151,000 took the exam in 2008, and 33,000 passed; in 2011, 332,000 (more than double the 2008 figure) took the exam, and only 17,000 passed (figure 2-8).

Figure 2-8. From 2008 to 2011, the number of students in Tanzania who completed secondary school doubled, but in absolute numbers fewer passed the examination.

Source: Author's calculations, based on CSEE data (Tanzania Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2012).

More Is Not Enough

More schooling is insufficient in itself to answer the need for improved basic education. The learning profiles by grade in the developing world today are just too flat. Reaching the Millennium Development Goal of universal primary schooling completion will not bring anything that could properly be called universal education. We know that with certainty, since many countries have met the Millennium Development Goal target and do not provide adequate education, with millions of children completing primary schooling lacking even literacy and numeracy. Moreover, even achieving universal basic schooling—or, at the shallow learning profiles often observed, even universal secondary schooling—would not bring most countries near a minimal threshold of learning.

This is not to say that aiming for universal enrollment and primary (and basic, and perhaps even secondary) school attainment is not important; of course it is. But as we near these goals, it is time to admit the world needs more than schooling, it needs more education. The difficult question is, can the same techniques that led to the success in expanding quantity work for learning?

1. Lewis and Lockheed (2007) discuss the “double disadvantage” of girls in poor countries, particularly from marginalized groups, who make up the bulk of out-of-school children.

2. These are transfers whose primary purpose is usually to transfer income to households, but making receipt of a cash transfer conditional on household behavior, such as the use of health services or child enrollment, has also been shown to have an impact on enrollment rates (Fiszbein and Schady 2009).

3. Oster and Thornton (2010), for instance, use a randomized experiment to evaluate the impact of menstruation control technologies on girls’ school attendance in Nepal (and find no impact).

4. See http://iresearch.worldbank.org/edattain/. I used the data from the 2010 database.

5. The Demographic and Health Surveys, funded by the United States Agency for International Development and implemented by ICF, and other surveys allow children to be linked to their households, and hence their enrollment can be linked not just to gender or rural/urban residence (which can be done with school-based data) but also to paternal and maternal education (Filmer 2000), household assets, and household wealth (Filmer and Pritchett 2001).

6. In the math section there were twelve questions common to grades four and six, eleven questions common to grades six and eight, three questions common to grades four and eight, and three questions common to all three grades four, six, and eight. In language there were six questions common to grades four and six, fifteen common to grades six and eight, and four common to grades four, six, and eight.

7. With the exception that the Uwezo standard for level 2 mathematics includes only multiplication, not division.

8. ASER uses one-digit into three-digit division as a benchmark that is supposed to be achieved by grade two, according to the Indian curriculum.

9. As in the previous chapter, the assumption about grade one levels is not about what a first-grader would in reality score on the TIMSS—a first-grader likely couldn't even read the test, and mechanically, I don't think scores are even meant to go this low. The assumption is entirely hypothetical and simply illustrates how a first-grader would perform on TIMSS-like units. The assumption of 100 as a minimum obviously biases the steepness of the learning profile down (compared to zero), but the assumption that progress is all learning (as opposed to persistence of better students) biases it up.

10. The technical problem is censoring. If we observe a fifteen-year-old who has only completed grade nine, he or she may later complete grade ten or grade eleven, while a fifteen-year-old who completed grade six is likely out of school. So the trade-off for a given survey is that older cohorts (such as those aged twenty-five to twenty-nine) would give less censoring and hence could estimate better the higher levels of the grade attainment profile, but would be less topical as they would be about education events often complete ten years or more prior to the survey. Since in most poor countries grade attainment through grade nine is very low, the choice was made to use cohorts aged fifteen to nineteen years and only estimate the profile through grade nine, where censoring is a minor problem.

11. These are “normal”-shaped in that they follow the equations of a Gaussian probability distribution, but the graphs are two-sided rather than the usual distributions, for entirely aesthetic reasons.

12. See www.oecd.org/document/61/0,3746,en_32252351_32235731_46567613_1_1_1_1,00.html.

13. PISA classifies students by their level of performance based on their score, where levels have specific descriptions in each of the three subject areas. Subjects have either five or six levels.

14. All points on the graph represent countries with the exception of Himachal Pradesh, India (HP-Ind), Tamil Nadu, India (TN-Ind), and Miranda, Venezuela (MI-Vez).

15. The descriptions of these basic levels are as follows: Basic reading (level 3): Interprets meaning (by matching words and phrases, completing a sentence, or matching adjacent words) in a short and simple text by reading on or reading back. Example test items: (a) uses context and simple sentence structure to match words and phrases, (b) uses phrases within sentences as units of meaning, (c) locates adjacent words and information in a sentence. Basic numeracy (level 3): Translates verbal information presented in a sentence, simple graph, or table using one arithmetic operation in several repeated steps. Translates graphical information into fractions. Interprets place value of whole numbers up to thousands. Interprets simple, common, everyday units of measurement. Example test items: (a) recognizes three-dimensional shapes and number units, (b) use a single arithmetic operation in two or more steps, (c) converts single-step units using division (SACMEQ 2010).

16. Comparisons with Botswana on TIMSS or Mauritius on PISA suggest these standards appear less stringent relative to grade level than the “international low benchmarks” of TIMSS or PISA (as many fewer are behind the level 3 levels than are behind comparable low benchmarks).

17. There is a close analogy with the distribution of income across households. If one knows the entire distribution, then one can talk about goals for average income, for inequality-adjusted average income, for poverty (those in the distribution below a certain point), and so forth, all based on the same distribution.

18. I am using data from 1995 and for females only, since that is when the question about reasons for dropping out, used below in table 2-7, was asked.

19. The school year deficit can be decomposed into the proportion of the deficit due to nonenrollment and due to children who enrolled but did not reach grade nine.

20. I chose grade nine because in many countries, schooling goals are moving to beyond primary school.

21. Intriguingly, the 1998 version of SACMEQ found that 55 percent of Malawian students achieved level 4 literacy or above, and in 2000 the cohort had completion rates of 45.5 percent. So, if the tests are reliable and the comparison is valid (the tests are meant to be comparable), then the fraction of a cohort with adequate literacy may actually have fallen over time, as the increases in enrollment more than offset decreases in learning.

22. The findings on this subject are rare, as most studies evaluate only additional attendance (e.g., Glewwe and Kassouf 2010 for Brazil) and are mixed, as some more recent evaluations have found learning impacts (e.g., Baird, MacIntosh, and Ozler 2010).