Chapter 1

The Man and His Life

The story of how a precocious young man from Winchester, Tennessee, grew up to become one of the most respected and wealthy professional investors of all time has been told many times, so much so that, as with many rich and successful men, discovering where the legend and the truth diverge is not always straightforward. John Templeton was a man of the highest personal integrity, but some of the stories about his rise to fame and fortune have, one suspects, lost something in the telling over the years. To judge by some of the conflicting details in different accounts of his life, certain facts have, with the passage of time, been either gilded for the benefit of effect, forgotten, or mixed up with one another.

It is generally true that hindsight tends to make an individual’s path to success appear smoother and more certain than, in reality, it was at the time. There is no doubt that John Templeton himself was fully aware of the importance of storytelling in building and sustaining an aura around his life and business success. Although shy by nature, he was an accomplished user of the media to advance his business career; a tireless publisher of books about his investment ideas and religious and philanthropic interests; and as a man, for all his genuine humility, not wholly immune to a certain amount of vanity. He had a sense of humor, but was not the kind of man to tell jokes. Yet there is no gain saying the extent of his achievements, or his remarkable record as a pioneer and exponent of the art of disciplined investment, an art he practiced and sustained over more than three generations.

What is not in doubt is that, rather like Warren Buffett, another of the twentieth century’s greatest investors, John Templeton was brought up with an unshakable determination to succeed. His self-assurance, allied to an unrelenting capacity for hard work and the ability to reduce complex analytical issues into a framework of simple but reliable heuristics, was instrumental in enabling his later triumphs as a professional investor. Determination and self-assurance were etched into his character from an early age. As a young boy, encouraged by his parents to be resilient and to show initiative, he showed a keen interest in enterprise.

At the age of eight, according to one of his earliest biographers, he was ordering fireworks from a manufacturer and selling them to other boys at his school for profit. As a teenager, unable to afford a car, he cannibalized the parts of two wrecked Fords, bought for $10 each, to create one vehicle in which he was able to drive himself and his friends around for the next four years, before selling it at a profit. When his school was unable to offer him the math instruction he needed to get into Yale, his chosen university, he persuaded the head teacher to allow him to teach an extra class in geometry and trigonometry himself, learning as he went along and ending (perhaps unsurprisingly) with the highest marks in the exam.

His drive to succeed faced its most severe test in the grim Great Depression year of 1931, when his father had to tell him that he could no longer support him in his undergraduate studies at Yale. The 19-year-old Templeton, by then in the second year of an undergraduate degree course in economics, had suddenly to find other ways to finance his studies. Recalling this early crisis many years later, he said: “At the beginning of sophomore year (which was two years after the great stock market crash of 1929) my father told me with regret that he could not contribute even one dollar more to my education. At first this seemed to be a tragedy; but now looking back, it was the best thing that could have happened. It caused me to begin studying really hard to get top grades and thereby maintain two scholarships to help with the expenses.” It also impressed on him that hard work and self-reliance were the keys to survival in life. “Seeming tragedy can be God’s way of educating his children,” he observed later.

“Mother had saved a little cash from selling vegetables and eggs, and I borrowed $200 from my Uncle Watson, which Mother paid back years later. This enabled me to travel to New Haven and to apply to the very well organized Yale Bureau of Student Employment, which was run by a capable man named Ogden Miller, who later became headmaster at the Gunnery School. He helped me to get scholarships and also to earn money at various jobs, such as being Senior Aide of Pierson College and chairman of the Yale Banner and Pot Pourri yearbook.”1

In addition to these worthy endeavors, Templeton took to playing poker with his fellow students to make up the shortfall in his funding—this despite the fact that in his later professional life, he was to bar his colleagues from investing in gaming stocks, as well as tobacco and drinks companies, on ethical grounds. Templeton estimated that he managed to earn enough from the poker table, using his knowledge of probability and his native quick wits, to pay for 25 percent of his fees. His remaining financial needs were met by a combination of the loan from his uncle, scholarships, and jobs at the university.

His time at Yale also saw him make his first stock market investment. “As a senior at Yale,” he told his colleague and biographer Robert Herrmann, “I earned $1,000 as the first Senior Aide of Pierson College. That was a tremendous help because it covered one-half of all that year’s expenses. When the 1934 accounting for the Yale yearbook was finished, about $800 in profit was distributed to me as chairman and was used to open an account with my roommate, Jack Greene. He was then senior partner of a stock brokerage firm in Dayton, Ohio called Greene and Ladd because his father had died during Jack’s junior year at Yale. This account is now 42 years old but the name of the firm has changed to Cowen & Company. My first purchase of any stock was the $700 preferred stock of Standard Gas and Electric Company, which was selling at 12 percent of par because of the Great Depression. From that original $800 and later savings have grown all of the investments I now own.”2

By this time, Templeton had already decided that he wanted to go into the investment business. After majoring in economics and collecting his degree from Yale in 1934, he won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford to study law for two years. At this most prestigious of English universities, he was taught by a law don at Balliol College, there being at that date no specialist tutors in business, let alone the lesser subject of finance. The idea that investment might become a distinct academic discipline was still many years in the future. Benjamin Graham’s seminal textbook Security Analysis, written with David Dodd, had been published in 1934; but John Burr Williams’ Theory of Investment Value, another landmark in the development of financial analysis, did not appear until 1938, having originally been written as a thesis at Harvard University.

Although he had certainly read Graham’s Security Analysis, which he later described as “the best book ever written” on investment, we do not know whether Templeton was familiar with the writings of John Maynard Keynes, whose most influential work, his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, was published in England during the 23-year-old Rhodes Scholar’s final year at Oxford. The General Theory contains some of the most famous passages ever written about the practice of investment, but if Templeton did read it, it seems that the world’s most widely quoted economist failed to leave much of an impression. We have failed to find a single line of Keynes, or any reference to him, in any of the scores of memoranda, articles, or press interviews in the Templeton archives.

Having finished his studies at Oxford, and before returning to New York to start his career, Templeton decided to take seven months to travel across Europe and Asia on a shoestring budget with a university friend, James Inksetter. During the course of this trip, he and his companion visited no fewer than 27 countries, observing the rise of Hitler at the Berlin Olympics and acquiring early experience of the world outside the United States. This experience was to stand him in good stead in his later career as an exponent of global investing, of which he was to become such a prominent pioneer. There were few countries with significant stock markets that he had not visited before he set up shop as an investment counselor, a discipline in which his knowledge and experience of other cultures and economies was evident from an early stage. The countries he visited for the first time included India, China, and Japan.

In his own words: “I finished Yale in summer 1934, so I was in Oxford for two years after that. Oxford I found was so different from American universities. They gave me six weeks’ holiday at Easter, and six weeks’ holiday at Christmas, and we Americans there took full advantage of that. I spent the second six weeks learning all I could about Germany, including listening to Hitler—I didn’t meet him, but I did listen to him. It was the build up to war, but it didn’t really involve America until Hitler invaded France.” Many years later Templeton returned to Oxford to found Templeton College, the first college in the university to be devoted to full-time management education.

The first job that Templeton found on his return to the United States was as a trainee at Fenner & Beane, a stockbrokerage that was later absorbed into Merrill Lynch. After only three months he was offered a much better paid job as treasurer at an industrial company, which sent him to Chicago, Dallas, and then back to New York. Two years later, aged 26, and by now married, he was ready to take the plunge and leave his job to set up his own investment advisory firm, which had long been his ambition. He later acquired the business of an elderly investment adviser in New York for $5,000 and set up office in the newly completed art deco skyscraper Radio City (now better known as Rockefeller Center). The purchase of the business was funded in part by a $10,000 loan from his former boss at Fenner & Beane. The loan was repaid after a year. It was the only time in his life that Templeton, who abhorred debt, and strongly advised against its use for stock market speculation, says he had been seriously in debt to anyone. (The loan from his uncle that helped him to complete his studies at Yale was, as we have seen, later repaid by his mother).

Templeton’s own account of his earliest professional experience is as follows: “Three months after I went to Merrill Lynch, one of my first mates was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, who said that he was Vice President of an oil exploration company and they had an opening for a treasurer. They offered me more than double what Merrill Lynch was paying me, and I thought I needed practical experience in how corporations operate, so I resigned from Merrill Lynch and was shifted by this exploration company, first to Chicago and then to Dallas and then back to New York. That took a little over three years. At the end of three years, I owned some shares in my employer. I bought out the shares, which they helped me buy, and that gave me enough money to live for five years without income. The truth is that I started out my life with no money whatever. I made my own way through Yale, and with scholarships through Oxford.”

This was true, although it would not be strictly correct to say that he came from a poor family. As he noted, once he had decided to set up his own firm, Templeton was not in the early years always able to draw a salary. Two years after acquiring the first investment counseling business, and getting his name above the door for the first time, he merged it with another larger firm, to create a new firm, Templeton, Dobbrow & Vance, in which he retained a substantial majority shareholding. Given his other commitments, it was perhaps just as well that the frugality for which he was to become well-known was already much in evidence. He and his first wife, Judith Dudley Folk, whom he had married in 1937 after a three-year engagement, vigorously embraced thrift as a way of life, furnishing their house with secondhand furniture bought at auction. She found a job in advertising and together they made a pledge to save, as a matter of policy, half of their joint incomes every month. (There are once again parallels with Warren Buffett, one of many successful investors for whom thrift is, or has become, an ingrained habit.)

“To make thrift a joy rather than a burden, we made a game of it by telling our plan to all friends and relatives, who then gave us ideas. We found a furnished Manhattan apartment with a view of the East River for $50 monthly. Our friends helped us find ‘blue plate’ dinners in restaurants for 50 cents. In 1940, the only Manhattan apartment we could find for $50 was on the sixth floor of a no-elevator building on East 88th Street. To furnish five rooms we could budget only $25. Our friends watched newspapers for furniture auctions when people were moving away. At such auctions if anyone bid $1 for a chair we said nothing, but if no one bid we said 10 cents. Our costliest purchase was $5 for a $200 sofa bed, which was so good we used it for 25 years.”3 With such “joyous games,” as Templeton described this self-imposed frugality, he and his wife furnished the apartment within the $25 budget. His tightness with money is a recurring theme in all his future professional colleagues’ accounts of their time working with him.

A second important episode in the Templeton story is that his first serious step as an investor was to decide, in 1939, just as World War II was breaking out, to go out and buy (sight unseen) all the stocks on the Big Board of the New York Stock Exchange that were priced at $1 or less. There are different versions of this story in print, but in the one that reads best, he even declined his broker’s offer to give him the names of the stocks he was buying. His argument was that the stock market was due for a recovery, and that even the most uncompetitive companies were likely to do well on the back of the stimulus provided by the inevitable increase in government spending that would be necessitated by the outbreak of war. So sure of his thesis was he that he did not even need to know the names of the stocks he was buying.

Templeton himself recalled this extraordinary stock market foray many years later: “The very day that happened [the German invasion of Poland], I said to myself that if there’s ever a time when corporations that are struggling come back to life is during a war. Following the Great Depression, there were more than 100 stocks on the New York Stock Exchange that had gone down to less than a dollar a share, so I called up Merrill Lynch and said, ‘Buy me $100 of everything below $1 a share.’ That proved to be very lucky. Within four years, I had four times my money.”

It is perhaps open to later generations to doubt whether this simple account of nerveless youthful investment genius was quite the whole story. Throughout his life Templeton was renowned for the thoroughness of his research; and indeed it was his study of previous episodes in financial history that had led him to conclude that low-priced stocks were likely to do better during the kind of wartime stock market recovery that he was expecting. It seems implausible, given the scale and audacity of the speculative investment that he was making, that he was not fully aware of the names of many, if not all, of the stocks he had instructed his broker to buy. Further, it is not wholly convincing that he made his decision entirely on the spur of the moment, the very day that Hitler invaded Poland, as his later telling of the story seems to imply.

It is worth recalling, too, that in today’s money, the $10,000 investment would be the equivalent of more than $150,000 dollars. Such a sum was many times the average income of the average American citizen, and twice the amount Templeton himself was about to pay to establish a foothold in the investment counseling business. For a young man of 27 it was certainly an audacious move, not least because it was effectively funded with debt, in the form of the $10,000 loan he had earlier taken out from his former boss in stockbroking.4 No fewer than 37 of the 104 stocks that the brokers acquired on his behalf were already in bankruptcy. It is tempting to say that few investments could have been more speculative, or less typical of the disciplined methods that Templeton was to advise others to pursue in his later career.

Although he was to become renowned in his later career as a long-term investor, who never failed to extol the virtues of patience and an even temperament, it is fascinating to speculate how much equanimity in practice a young married man, even one as self-confident as Templeton, was able to muster as he waited for his massive speculative gamble to play out. Did doubts enter his mind at any point during the four years he held on to his portfolio of third and fourth rate stocks? It is worth remembering that his investment decision was, not for the first time in his career, well ahead of events. His $10,000 purchase of stocks was made more than two years before the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor, which was the trigger for President Roosevelt to take the Americans into the war, something many of the Allies on the other side of the Atlantic, from Winston Churchill down, were far from convinced was going to happen.

If, as he later recalled, the $10,000 loan was repaid within a year, it seems unlikely that this could have been solely the result of any rapid increase in the value of his stock portfolio. Although the price of stocks on Wall Street rose on the day that Germany invaded Poland, and again the day afterward, they did not break out decisively above their level on September 3, 1939 for more than three years. The Dow Jones index fell by 12.7 percent in 1940 and by 15.4 percent in 1941. It was not until April 1942, five months after Pearl Harbor, that the stock market finally began the significant wartime rally that Templeton said that he was expecting to follow the outbreak of war. The index did not surpass its level on the day Britain declared war on Germany until after the invasion of Normandy in June 1944. Four years on from his original purchase, on September 1, 1943, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was less than 2 percent higher than it had been on the day he made his first investment. Of course, many individual stocks fared much better than the average. There were good reasons for believing that near-bankrupt companies would fare better than the averages.5 For his portfolio to rise by 100 percent in 12 months in a flat market, and by 300 percent over four years, as his account suggests, was therefore a remarkable achievement.

A more realistic assessment may be that his analysis, as was true so often in his career, was correct, but that his decision to invest was some years ahead of events. The outbreak of World War I had been followed by a surge in the American stock market, but after an initial two-day rise this was not what happened in 1939. The assumption was wrong. Many years later, in a letter to his clients, Templeton noted how many weak or failing companies had subsequently produced exceptional results.6 Wartime saved many companies that otherwise might not have survived. The worse their balance sheets were, the more leverage they enjoyed. More than 200 companies had risen by 20 fold or more in the previous 20 years. Yet it is notable that most of these companies had experienced their lows in 1941, not in 1938. In other words, while Templeton was vindicated by later events, the timing of his speculative foray, so different from his later investment style, was distinctly premature.

Recalling his early days as an investment counselor in an interview 60 years later, he said: “When I opened my own office in Radio City, I must say I made a lot of mistakes. Perhaps the biggest mistake of all is to start out like a law firm does, or like a medical firm does, and hope that your reputation alone will attract customers. I tried that. In fact that was the standard among investment counselors. When I started out, I would have been looked down on if I had done any advertising. The result was that it took a long time to accumulate clients. Now that it is acceptable to be a salesman, I would surely think you ought to spend three-quarters of your time selling.” This was a theme, as we shall see, which was to recur when Templeton later moved into the mutual fund business. Sometime after opening his office in New York, in order to save money he moved the bulk of his operations to the suburb of Englewood, New Jersey, 45 minutes away from the center of Manhattan.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s Templeton and his partners continued to build up their investment advisory business. Wartime and the subsequent Cold War provided early lessons in the wisdom of controlling clients’ exposure to the stock market. Templeton was one of the first firms to attempt to regulate clients’ exposure to the market on the basis of a quantitative assessment of the current level of the market, an approach that came to be known as the Yale or Vassar method, and which we describe in more detail in the next chapter. The key elements of this method were to reduce market exposure when it had become overvalued and increase it when it became undervalued against historical experience.

Nothing sounds simpler or more logical. Buying low and selling high has been the street trader’s watchword since markets began. It is, however, something that most investors find much harder to achieve in practice than it should be. Templeton’s analysis was based on comparing the level of the market in a rigorous fashion with the earnings, cash flow, and yield characteristics of both the recent and more distant past. It proved to be a useful tool that, by his own account, was to help steer the firm’s clients safely through the bear markets of the late 1940s and 1950s, while inevitably sacrificing some of the upside in the stock market’s best years. It was only later that he was to develop the practice of basing his individual stock selection on forward rather than historic earnings.

In 1954, looking for new ways to expand the business more quickly, Templeton decided to launch a new mutual fund. This was the Templeton Growth Fund, domiciled in Canada. It was unusual in being one of the very first mutual funds to offer North American investors the opportunity to invest in a managed fund that set out to invest across the globe. At the time, it was still a commonplace view among investment professionals that it was too risky to commit anything but a small proportion of their assets to investment opportunities outside the United States. In addition, legislation prevented many pension funds and charitable foundations from investing in securities outside the United States. The fund itself was the first of a number of new managed funds to be domiciled in Canada, where there was no capital gains tax. The tax advantages of the fund had obvious advantages to a U.S. investor, and they duly featured prominently in the way that the fund was marketed.

Behind those immediate benefits, however, were the seeds of a distinctive new investment philosophy. Templeton’s argument, still a minority view at the time, but now mainstream thinking, was that widening the range of potential investment opportunities could only increase the universe of potential bargains, to the benefit of investors. His view had always been that the risk of global investing is exaggerated and can in any event be offset by diversification. “Research shows that a stock portfolio with investments around the world is likely to yield, in the long run, a higher return at a lower level of volatility than will a simple, diversified single-nation portfolio. Diversification should be the cornerstone of any investment programme.”7 (It is a neat coincidence that the Templeton Growth Fund was launched just as the future Nobel Prize winner Harry Markowitz was demonstrating that diversification across poorly correlated asset classes could reduce investors’ exposure to risk without jeopardizing returns, an insight that underlies much of modern financial theory.)

For many years investor interest in the Templeton Growth Fund was limited. Its performance was strong in absolute terms, capitalizing as it did on the 1950s postwar recovery in equities, but it remained little known and poorly followed. For the first 10 years, as we show in Chapter 3, it would have struggled to keep pace with the MSCI World Index, had such a thing existed at the time. Any investment consultant who monitored its performance at the time would have been forced to conclude that it was a slow developer. Later, however, the performance of the fund was to improve dramatically and as its track record became better known through the efforts of his new partner Jack Galbraith, who came in to market it, more investors and intermediaries began to take notice. Other firms also began to offer similar global funds, and before too long the mutual fund industry was growing at a furious pace.

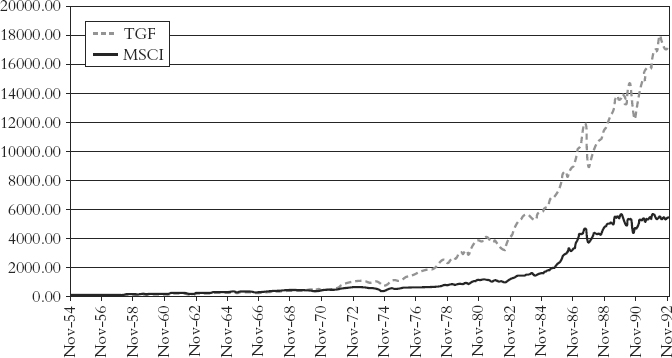

How, we asked him, did the change to a marketing-backed business come about? Templeton replied: “I was sitting in my office one day and a man came in and said he had been an airplane pilot during the war, but now he wanted to be a salesman. He thought I had a good performance in investments, and asked: Could he sell my mutual fund? I said, ‘I don’t have any money to pay you’ and he said, ‘That’s all right. I’ll just take a commission.’ His name was John Galbraith, and he started out by taking performance charts of my fund in Canada, the Templeton Growth Fund in Canada.” (The charts showing Templeton Growth Fund’s extraordinary track record of performance later came to be known inside his firm as “the mountain,” in recognition of its succession of soaring peaks.) See Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

Figure 1.1 Templeton Growth Fund Cumulative Growth

Source: Templeton Working Paper: A. G. Nairn and M. F. Scott, “A Data Study of Historic Returns in World Stock Markets 1953–1997”; Datastream/ICV.

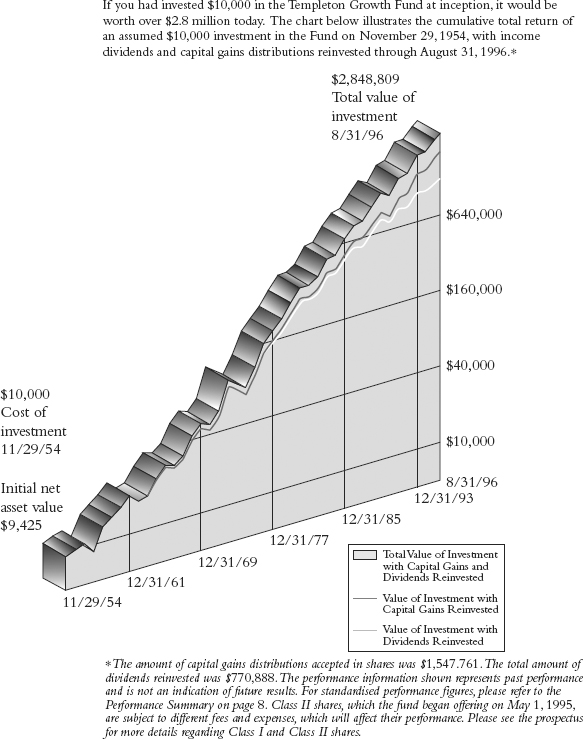

Figure 1.2 Templeton Growth Fund Class I Shares

Source: Nairn, Templeton Growth Fund, Annual Report 1996.

According to Templeton’s biographer, Jack Galbraith was a trained accountant who had spent a number of years working in the fund industry before approaching Templeton with a proposal to help market his fund. In Templeton’s account, “His wife ran everything except the calling on brokers, which he did himself. He would walk into a broker’s office and see somebody who wasn’t busy and sit down beside them and say: ‘Tell me, what mutual fund has the best results?’ They would name some firm, and he would say ‘Look at this,’ and show them the chart of the Templeton Growth Fund. That caught their attention, and so a large number of them began to sell the fund to clients. He paid them a commission and he kept a commission for himself. It worked like magic.”

According to Templeton’s official biographer, Robert Hermann, Galbraith had originally proposed a deal under which he could eventually acquire the fund’s management company if he succeeded in increasing the assets of the fund tenfold over 10 years. Templeton declined this offer, but instead suggested that Galbraith acquire 20 percent of the fund’s management company at the outset. This the latter did, although not before telling his wife that he had been disappointed to have ended up with “only half a loaf” instead of “the whole loaf” he had wanted. The management company stake was to become worth many millions of dollars, and make Galbraith a very wealthy man.8

It was, ironically, only in the 1970s, however, as Galbraith and his wife began to build a larger marketing team, that the Templeton Growth Fund began consistently to outperform the market. Until that point its track record had been impressive in absolute terms, but still had a tendency to underperform the markets it was investing in. It was during this period that Templeton began to invest heavily in the Japanese stock market, a contrarian move that was to play a large part in establishing his later reputation. At the height of this phase in its life, the Templeton Growth Fund had as much as 60 percent of its assets in Japanese stocks. Yet at the time few professional investors would touch Japan, so little known or understood was the country. Having visited scores of countries on his regular travels abroad, and with an insatiable appetite for new information and experiences, John Templeton was ideally qualified to introduce thousands of American investors to the benefits of investing in international stocks.

Templeton’s partnership with Jack Galbraith proved a huge commercial success. Within four years the Templeton fund range—later expanded from the Growth Fund to incorporate a number of other funds managed on the same principles—had grown in size from $13 million to $100 million. By the 1980s, helped by the pro-business policies of the Reagan administration and the onset of the greatest bull market of the twentieth century, the fund was measuring its assets in billions, rather than millions, of dollars. By the time the business was sold to Franklin Resources in 1992, the firm had assets of $21.3 billion, spread across a range of more than 70 funds, including a well-known emerging market fund managed by Dr. Mark Mobius, which had been launched in 1987. Templeton and his colleagues received several hundred million dollars from the sale of the fund management and distribution companies they owned. Templeton personally, his son Jack, and his business partner Galbraith owned 70 percent of the voting stock in the business, according to press reports.

It is worth emphasizing that not everything ran smoothly at all times. During the savage bear market in the early to mid-1970s, for example, the value of the Templeton Growth Fund fell sharply in three out of five years. The net asset value declined by 9.9 percent in 1973 and by a further 12.1 percent in 1974. The saving grace was that the fund’s loss of value was less severe than the decline in the main market index, reflecting the defensive qualities of Templeton’s rigorous value-oriented approach. It was a setback nonetheless. In 1974, the combined value of all the funds managed by Templeton amounted to no more than $13 million, a tiny fraction of the $90 billion empire that it was to become over the course of the next 30 years.

Another irony is that it was partly an accident that Templeton was still engaged in active money management at all when the bear market of the mid-1970s hit. In the late 1960s, by then already wealthy from the sale of his advisory and other investment businesses, he had decided to move his base from the United States to the Bahamas, where he was building a house on an exclusive private estate known as Lyford Cay. Templeton had sold all his other business interests in the hope of retiring to spend more time on his charitable interests. Despite its later spectacular success, the reality is that he had been unable to find a buyer for the Templeton Growth Fund at the time. The family who had bought his other interests decided that they did not wish to acquire the fund.

As a result he decided to continue to manage it himself. He set up a small office above the local police station near his new home in the Bahamas, where he continued to live from 1968 until his death 40 years later. Working with minimal resources (and distractions), he said that he spent an hour a day on the beach scanning scores of research reports, looking for stocks that he considered to be bargains. Being so far from the noise and bustle of Wall Street was, he quickly became convinced, a powerful contributory factor to his continued ability to do better than most of the big professional firms at the heart of New York’s financial district.

With the advantage of hindsight now, I think there are two reasons for this success. One is that if you’re going to produce a better record than other people, you must not buy the same things as the other people. If you’re going to have a superior record, you have to do something different from what the other security analysts are doing. And when you’re a thousand miles away from Wall Street in a different nation, it’s easier to be independent and buy the things that other people are selling, and sell the things that other people are buying. That independence has proved to be a valuable help in our long-range performance.

Then, the other factor is that so much of my time in New York was taken up with administration and in serving hundreds of clients that I didn’t have the time for the study and research that are essential for a chartered financial analyst. And that was the area in which God had given me some talents. So now in the Bahamas I had more time to search for the best bargains.9

He had earlier told another biographer William Proctor: “When my wife and I were looking for the best place to live, one of the questions we asked was ‘Where can we carry on our work in the most pleasant surroundings?’ . . . All my life I’ve enjoyed the open air, and especially the flowers, ocean beaches and clear water of the tropics. We were attracted very strongly to ocean beaches, and now that we live here we are surrounded by three ocean beaches. So I use every opportunity when I can get away from routine work and telephones to take a briefcase full of papers and sit in the shade on the beach. There I concentrate either on security analysis, or on religious reading or study. I find it’s an excellent place to work. You can work with greater concentration there than you can in an office or in a home.”

Templeton went on to say that while his family investments and charitable activities took up most of his time, the fund was not neglected. “I spend, at most, an hour a day at the beach thinking and doing my work. . . . There are too many demands on my time to spend any longer. But I do it almost every day I’m not traveling, and that turns out to be about 150 days a year. It’s a very pleasant time of withdrawal, and the interesting thing is that it seems to be productive, too, in terms of producing good overall results for our mutual funds. To be able to work with the sand and ocean surrounding me seems to help me to think in worldwide terms.”10

Market Guru: Global Contrarian

Time and the market cycle also proved to be on his side. Having correctly spotted the potential explosive growth of the Japanese stock market in the early 1970s, by the end of that decade Templeton had switched his main focus of attention back to the American stock market. As early as 1982 he was announcing to the world, and indeed anyone who cared to listen, that he expected the U.S. stock market to boom over the coming years. It was a theme that he was to return to time and again over the next 15 years. It was also vindicated by events, as stock markets around the world, led by the United States, embarked on what was to prove the longest and most sustained bull market of all time.

In 1982, for example, he went on the TV program Wall Street Tonight to declare that there was a better than even chance that the Dow Jones Industrial Average, then trading below 850, could hit 3,000 within 10 years. In the event the market hit 3,000 in 1991, confirming Templeton’s status as a market guru. Although with hindsight this looks like an obvious call, at the time it is easy to forget that many pundits were writing off the American stock market after nearly a decade of indifferent or calamitous returns. In August 1982, the same year that Templeton made his prediction, BusinessWeek had famously produced a cover story that announced “the death of equities.” In 1993 he predicted that the Dow Jones index would hit 6,000 before the end of the century, which it duly did in 1996, before going on to peak at a remarkable 11,723 in January 2000.

The 1970s was the start of a period that saw his reputation as a market guru rise by leaps and bounds. Whereas before John Templeton had been a respected but largely unknown figure outside the narrow circle of Wall Street, now in his 70s he was being hailed as one of the most famous investors of his generation. In all he made 15 appearances on Louis Rukeyser’s widely followed TV show Wall Street Week, mostly to reiterate his message that the times were good and that this was an outstanding opportunity to invest in the United States stock market, as indeed it proved to be.11 Galbraith’s marketing and PR efforts transformed the fund’s visibility and helped to propel its fund manager into national prominence, exemplified by the first of several appearances on the front cover of Forbes magazine in 1978.

By this time, too, Templeton had firmly established his reputation as a contrarian investor. Alongside his faith in the merits of global investing, he had long been convinced that the most reliable way of achieving the best returns was to concentrate on finding bargains wherever they could be found, regardless of prevailing fashion or sentiment. By definition this meant buying things that most other investors did not want, and extending the search for bargains right across the world, anywhere stocks were traded in size. “People are always asking me where the outlook is good, but that is the wrong question” he said on more than once occasion. “The right question is: Where is the outlook most miserable?”12

The implication also was that it could take time for valuation anomalies to be put right. These insights remain at the heart of the Templeton investment philosophy. This philosophy can be summed up like this: “Buy stocks for less than they are worth and hold them as long as it takes for the market to appreciate how undervalued they are.” By definition also, this clearly implied that finding the best bargains could only be achieved by being prepared to go against conventional wisdom.

In formulating his approach, Templeton acknowledged his debt to Ben Graham, the so-called father of security analysis, whose pioneering book Security Analysis, written with David Dodd and first published in 1934, Templeton had read while an undergraduate. The book set down a series of analytical techniques for assessing the value of securities, all of which Templeton has subsequently used at different times as part of his own formidable analytical method. However, as will become clear, it is too simplistic to characterize his approach as pure value investing.

A key part of Templeton’s analytical technique is not just to look at company’s current earnings, balance sheet, and cash flow. What matters to an investor is how earnings and cash flow are likely to develop in the future, not where they are today. As Mark Mobius, one of Templeton’s best-known disciples, puts it, “you have to look at the future, not just at today.” The technique that Templeton developed at his firm was to make sure that all the key variables of a potential share purchase should be projected several years into the future.

He argued that a share that does not meet conventional value criteria, such as a high dividend yield or a low historic earnings multiple, could still be an attractive purchase if the key performance parameters were set to grow in the near future. By definition, therefore, a Templeton-influenced investor is interested in both growth and value. Or, as Templeton himself put it in an interview once: “Looking for a good investment is nothing more than looking for a good bargain.”13 Anything, in theory, could qualify. It was the combination of price and growth potential that was critical. Where he differed from classical deep value investors such as Ben Graham was in recognizing that historic valuation metrics were not sufficient to produce a bargain. His first and most famous fund was labeled the Templeton Growth Fund for a reason.

Mark Holowesko, his former assistant and chief investment officer, still occupies Templeton’s office building in the Bahamas, but now runs his own fund management boutique. He gave us his personal reflections on the 15 years he spent working with John Templeton. This is how he recalled his early years:

Sir John was a unique employer in many ways. For one thing, he paid me by the hour, even though I had a Masters degree! He didn’t care if I took three days off in a row and then worked 20 days in a row, as long as I was only paid to work so many hours a year. At the end of every week, I’d write a little note to him saying I worked so many hours, and he’d get a pen, write a check for me, and leave it on my desk. We did that for much longer than you would believe.

I still have my first rejection letter from Sir John, where I asked him for a job and he turned me down, but wished me good luck in the future. I also still have my first raise, which was in November 1985. After six months he very kindly gave me an increase of $1.50 an hour. Now I could afford cheese on my hamburger! It gives you some of the character of the guy. When I first started working for him, he always worked on hotel stationery because it was cheaper. Because it was half a cent a page cheaper to buy loose-leaf and staple it together, we had loose-leaf instead of legal pads. You could go on for days with stories like that.

Working for him was incredibly tough. Here was someone who used to come into work seven days a week. He’d come into work after church on Sundays. You were always behind him. He always drove you to do more than you would have done, just to try and keep up with his pace. Even when he was 75, he never let up. He’s obviously brilliant, but his genius, I think, lies in his ability to take complex things and break them down into issues that are simple. His rules on investing sound very simplistic, but aren’t. He could run circles around the guy who has got a Harvard MBA but who is looking at the world in too complex a way.

I got a job with him in the end because I wanted to take the CFA exam. I wrote to him and explained that you need another CFA to sponsor you, and he was the only one on the island. Would he do it? He said sure. After I passed the first level, I wrote him again and that was when he invited me in for an interview. My first job was basically legwork. He came in during the Bhopal disaster, for example, which was a big issue for Union Carbide, and said, “What sort of liabilities were involved in similar instances in the past? What would the potential liability be for Union Carbide?” His attitude was: “Okay, here’s a problem. The stock price is down tremendously, let’s just put some numbers around the problem and see what the market discount is.” That’s the sort of thing that I would do on his instruction.

Eventually I started picking stocks on my own, recommending ideas. Then I took on research responsibilities, then research responsibilities for the group. After that I took on account management responsibilities, managing separate accounts. Eventually in May 1987 he came in and he put all of his mutual funds on my desk and said: “From now on, why don’t you write up the trade tickets, what you think should happen to these funds and leave them on my desk?” People say Sir John’s a stockpicker, not a market timer, but as he handed over the management of his funds in May 1987, I think he was a pretty good market timer too! It was a baptism by fire. [The U.S. stock market was to suffer its largest ever one-day fall in October 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by more than 500 points, a decline of 22 percent]. In 1989 I became Director of Research and then eventually CIO. It’s been a fun, exciting ride.

One of the authors, Sandy Nairn, also recalls his early years working for Sir John as being unorthodox in their simplicity.

I joined Templeton in 1990. Part of the process involved flying over to see Sir John and a couple of other people. My first big impression was the contrast with my experience when I joined my previous employer. The chief executive there didn’t know my name. It was only a small company, but he had no involvement with the hiring process at all. It was all very hierarchical.

Yet I went to Nassau and here was one of the world’s legendary investors sitting down and talking to you about your background and what interested you. It was clear that this wasn’t a job for him, but a vocation. What really struck me was that he was the chairman of the company, owned the company in fact, and yet he knew as much about any of the stocks in the funds as anyone else in the company—in fact, probably more.

My second clear impression is that he didn’t talk very much. Everyone else I’ve ever dealt with has talked. You just listened and occasionally responded. Sir John had an uncanny knack of letting you blather on indefinitely. He just soaked up information, and put you at ease. He had delegated the management of the company to Tom Hansberger, largely I think because he wanted to remain directly involved with the investments.

Again this was the exact opposite of where I had come from. There, people couldn’t get out of the investment business fast enough! They wanted to get themselves away from responsibility for making investment decisions. The attitude was very much: Junior people do company analytical work. At worst, the guys at the top were portfolio managers; at best they were “strategists” or even completely divorced from it. But for Templeton, it was the complete opposite; as far as he was concerned there was no higher form in life than being an analyst. The amazing thing is that he would have been 77 or 78 at this time.

Everyone who went to see Sir John tried to figure out the secret of the Templeton approach. In fact he’d tell you it all in the first five minutes, but you just didn’t notice it. I know that my head was full of unconnected ideas at the time, like a tin full of broken biscuits. I knew about every investment technique in the world, but not about how to join them together, he just said to me: “buy cheap stocks.”

There is a danger that you think this is too simplistic. Doesn’t he know about this, that and the other technique, you could ask? The trouble is that he absolutely did know these things. He absorbed them all and yet he still came back to this simple approach. My view is that the level of clarity he had about the big issues is what defined his genius.

I remember an example in the 1990s, when the fund I was running had had 18 to 20 percent in emerging markets, but I had reduced this to 3 percent, while everyone else in the industry still had a weighting of 20, 30, 40 percent. I asked him what I should do and he just said: “In all my 45 years of investing, I have never thought it sensible to buy expensive stocks for my clients.” And that was it—next topic! His attitude was: “I don’t care what everyone else says unless they can show me why I’m wrong in my judgment about the value of a company.” The truth is that all he has ever cared about is what things are worth. If a share was worth too much, then he thought you should sell it. It was as simple as that.

He was very careful with the selection of people he would employ, and that’s why he spent time with them, because he was entrusting the future of the company to them. His CEO at the time was a wonderful character who hired people from very different backgrounds, anything from the straight laced to the mad party animal. It made for a very different atmosphere. We all got on very well and had a lot of fun, because we were all very different. What he didn’t do was pick only people from the top business schools where they are all dragooned into thinking in a particular way. I think he just loved diversity.

Mark Mobius, who now runs the Templeton/Franklin group’s range of highly successful emerging markets funds, recalled his own first dealings with Templeton.

It all started in 1985 and 1986 when I was working for a brokerage company. They sent me to Taiwan to take over the management of a joint venture, the first of its kind in Taiwan at that time. After about a year and a half, I get a call from Sir John and from Tom Hansberger, his business partner, asking me to be the manager of a new fund they were setting up, the Templeton Emerging Markets Fund.

After some negotiating I came onboard and started running that fund, which was then about $100 million in size. By 1994 it had grown to be worth $14 billion. [Today it has grown to $40 billion.] The foresight that Templeton had in taking on this fund with Merrill Lynch, who had originally started it, told me something about the man. He had been looking at emerging markets for quite some time. He was a bargain hunting global investor who was willing to go into markets where others feared to tread.

It was difficult to leave Taiwan, but I decided that this was a chance to leap into something more exciting. It certainly wasn’t the money. I wasn’t going to get paid any more than I was making, and I had a lot of perks in my job in Taiwan. I had a driver and all that stuff. But those types of things don’t really impress me, and I was more excited by the prospect of what was coming. As it happened, things just went from good to better. In hindsight it was the right decision because in Taiwan, at most I would have managed a billion dollars. Under Templeton I ended up with a lot more than if I had stayed where I was. It really has turned out very nicely.

Fortunately I bought into his way of investing right from the start. I can’t really remember why, because I was interested in technical analysis for a long time and I taught some of that at the Chinese University in Hong Kong. When they expounded the Templeton philosophy, however, I think it just made an awful lot of sense. His genius was that he could simplify things to make it easy for anyone, even someone as thick-headed as me, to understand.

One of his key insights was to realize that valuing a stock by reference to the price-earnings ratio today is far too simplistic. He would say: “Oh no, we don’t want to look at what the P/E is today. We want to look at what the P/E will be in five years. Let’s look at the future, not at the past.” His approach was really growth and value. I would say that that is one of the things he had added to Graham and Dodd. He also believed in flexibility. There is a tendency for people to become rigid, which is not a good idea.

The other aspect of working for Sir John is that he pretty much left us alone to do our own thing. Of course he gave us guidelines on how to work, but generally speaking he was hands-off. Whenever we needed help, he would give it, but he mainly let us run our own show. We never had any formal contact on how to invest anything, except at board meetings. That was a formal report of what we were doing. Other than that, the only real guidance was “keep on looking for those bargains”!

Anyone who has met John Templeton has been struck at once by his politeness, his extraordinary capacity for hard work, and his ability to focus single-mindedly on the task in hand. According to Holowesko, his assistant in the Bahamas for many years, Templeton was always fastidious about using his time to maximum effect. Gary Moore, a longstanding friend of Sir John who advised him on ethical investment, recalls that a typical appointment would last “from 8:02 to 8:13.” Once the business was done, it was always on to the next task without a moment’s break.

Jack Galbraith, Templeton’s business partner, recalled the same thing. “By nature he doesn’t want to waste time—so you don’t ever find yourself sitting around exchanging small talk. You always have a sense that he has more things to do than time to do it. . . . Just as he respects his own time, Templeton extends that respect to the time of others. John Hunter, one of his Canadian stockbrokers, says that when he tells him that he will call at 9:15 Canadian time, the call will invariably come through at precisely that time—from wherever Templeton is traveling in the world. In fact, to ensure that he is prompt, he has always set his watch 10 minutes fast.”14

Hard work, punctuality, and commitment are qualities that Templeton tried to impress on all those he met and worked with. During his working life, he made a habit of carrying a book or a stack of research reports with him so as not to have waste any time while traveling. His notorious thrift extended to all aspects of business life. When Holowesko started working for Templeton, to give just one of many possible examples, he was instructed to staple together bits of scrap paper so as to save on the cost of buying new stationery. When asked whether the founder was really as careful with money as his reputation suggested, Jim Wood, who led the marketing for the Templeton firm’s institutional accounts business in the late 1980s and early 1990s, replied, laughing: “My guess is he died with his first nickel in his pocket!”15 When a group of potential Chinese investors arrived in the Bahamas to meet him, he recalled, Templeton presented them all with a cheap alarm clock “that cost about five bucks apiece,” which was “somewhat embarrassing.”

He could, however, be generous to his employees, Mr. Wood recalls, and although he was to become fabulously wealthy in his later years, he never lost touch with his origins. “I don’t think that Sir John really cared how much money he was making. He never had any money growing up, and I don’t think he cared a whole lot. He was doing what he wanted to do, and he just thought that if he kept working, the rest of it would take care of itself. During the first 15 to 20 years of the Templeton Growth Fund [when the fund barely grew in size], I guarantee he never got close to jumping out of the window!”

Throughout his life, Templeton relied on his Christian faith to sustain him through adversity. Never was this more needed than in 1951 when his first wife Judith died after a motor accident. Templeton was left with three young children to bring up, as well as the demands of running his own business. According to his friends, he coped with this appalling reverse with great resolve, convinced by his faith that it was futile to challenge “God’s design.” Five years later, he married his second wife Irene and lived contentedly with her until her death in 1993. His eldest son, John Templeton Jr., has for many years taken a keen interest in the business that his father founded, but always insisted that he had no intention of competing in the same business while his father was alive. Instead he pursued a highly successful career as a pediatric surgeon.

After selling the business, John Templeton lived quietly but productively in the Bahamas, where he was well known as a generous local benefactor. He worked from a new office building just outside the gates to the Lyford Cay estate, and a short walk from the first floor room above the police station, which had served as his office when he first came to the Bahamas. The new office was built shortly before the sale of his fund management business in 1992. It is from this building, and with the help of his long serving administrative staff, that he continued to administer his wide range of philanthropic and charitable activities until his death on July 8, 2008. The Templeton Foundation itself operates from West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, while the fund management operation, now part of the Franklin Templeton group, remains in Florida, where it had been set up in the 1980s to handle the administrative and marketing operations of the Templeton funds.

With his love of work and serious purpose, John Templeton was, some felt, easier to admire and respect than to know well. The Canadian fund manager Peter Cundill, an exponent of Grahamite value investing, met John Templeton on several occasions, and described him as “something of a mentor.” After a business meeting in Lyford Cay, having been across to see the older man, he noted in his diary: “He is extraordinary in the breadth of his skills and interests, and yet he can be so dry and seemingly humorless, even egotistical and mean-minded. He is a highly complex personality—for all the beaming patriarchal smile—and yet I always have to acknowledge that he has given me enormous help not just in financial matters but in spiritual ways too. Somehow I still can’t imagine having a warm dinner with him where the reserve is abandoned. Maybe it will happen one day.”16 His colleague Jim Wood, although he developed an excellent working relationship with his boss, and had regular discussions with him, says: “I think he tried, but it just wasn’t in him to be warm and fuzzy.” He almost never watched television or movies, and hardly ever read a novel.17

In 1972, Templeton established the Templeton Prize, an annual award that was originally conceived to do for religious studies what the Nobel Foundation does for academic and intellectual work. By design the prize is the most lavishly endowed of any in the world, but was not, he felt, as widely acknowledged as it deserved to be. In more recent years the Foundation, founded in 1987, has quietly modified its objectives away from the ostensibly religious to encourage and support scientific analysis of big questions related to human purpose. At the end of 1989 it had assets of $1.7 billion, making it one of the 40 largest foundations in the United States. Templeton published a series of books offering practical advice to young people on how to advance their spiritual awareness. He also gave money to schools and other local communities to encourage them to instill in young people what he liked to call “the laws of life.”

Notes

1. Robert L. Hermann, Sir John Templeton (Philadelphia and London: Templeton Foundation Press, 1998), 111–112.

2. Hermann, Sir John Templeton, 111–112.

3. Ibid., 125–126.

4. An alert reader will notice that it is not entirely clear whether the loan was intended to finance the stock market investment or the acquisition of the investment counseling business.

5. The memo is entitled The Fortune Makers.

6. Ibid.

7. Norman Barryessa and Eric Kirzner, Global Investing the Templeton Way (New York: Irwin Professional Publishing, 1993), Foreword.

8. Hermann, 144.

9. Herrmann, 140–141; originally from Proctor 109–110.

10. William Proctor, The Templeton Touch (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1983), 114.

11. At its peak, Wall Street Week claimed an audience of 4 million viewers, which it claimed was greater than the readership of the Wall Street Journal.

12. Lauren C. Templeton and Scott Phillips, Investing the Templeton Way (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 17.

13. Proctor, 59.

14. Hermann, 135.

15. Interview with the authors, September 2011.

16. Christopher Risso-Gill, There’s Always Something to Do; The Peter Cundill Investment Approach (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011), 116.

17. The Templeton Touch, 92.