The Egyptologist knows that never was there a race more fond of life, more light-hearted, or more gay. A lovable trait is the evident equality of the sexes: both in the reliefs and in the statues the wife is seen clasping her husband round the waist, and the little daughter is represented with the same tenderness as the little son.

—Sir Alain Gardner1

O what miserable and perfect copies have they grown to be of Egyptian ways! For there the men sit at home and weave while their wives go out to win the daily bread.

—Oedipus despairing over his sons in Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus

The Egyptians founded their civilization in the Nile River Valley. Evolving a writing system entirely different from cuneiform, the Egyptians invented a pictorial script we call hieroglyphs. The appearance of these distinctive figures in 3000 B.C. marked the beginning of Egyptian civilization.

Though based on images, Egyptian script was more than a sophisticated form of picture-writing. Each picture/glyph served three functions: (1) to represent the image of a thing or action, (2) to stand for the sound of a syllable, and (3) to clarify the precise meaning of adjoining glyphs. Writing hieroglyphs required some artistic skill, limiting the number chosen to learn it. Despite its complexity, hieroglyphs were a surprisingly expressive writing system.

The aesthetic sense guided the arrangement of the icons more often than did the dictates of grammar. For example, a tall icon had to precede a short squat one, even if the thought order suggested that they should be transposed.2 In many instances, the reader grasped the meaning of the sentence by recognizing the patterns of all the icons in it simultaneously.3

While hieroglyphs were able to express most ideas, some concepts presented a challenge for a language based on pictures. To solve the problem, the Egyptians invented twenty-five icons to represent each of their language’s spoken consonants and thus allow the reader to sound out a word-concept anacrostically. This is the principle of the alphabet. Although the Egyptian scribes had developed the first rudimentary alphabet, they used this new shorthand sparingly. They failed to recognize how useful and economical a small number of signs corresponding to the individual phonemes of their spoken language could be.

As would be expected of a people whose writing system was based on concrete images, rather than abstract figures, Egyptian mythology featured benign creation stories compared to those of the Babylonians. In one of the oldest, dating back to the Early Dynastic period (3100-2680 B.C.), two primordial female deities—Nekhbet, the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt, and Wadjet, the cobra goddess of Lower Egypt—emerged out of chaos. After cooperatively bringing forth the world, they created the Egyptian people, who were linked by their dependence on the Nile River.4

While the vulture may not seem a very appropriate symbol of the female essence, the ancient Egyptians believed that all vultures were exclusively female (the hieroglyph for mother and vulture are one and the same). Vultures, a divine manifestation of death, represented an important aspect of the Goddess. And vultures seemed to possess foresight, as evidenced by their circling a potential meal long before dinner was a certainty.

Western culture has long reviled the snake, associating it with evil and temptation. But at the dawn of civilization the snake was a positive symbol of feminine energy. Egyptians perceived the snake as a beneficent, vital creature intimately associated with female sexuality, and, by extension, with life. A snake’s sinuous mode of locomotion is evocative of a nubile woman’s walk and dance. Her movements in the throes of lovemaking are serpentine in contrast to the mechanical pumping of the male. In some cultures, orgasm has been likened to releasing the latent energy of a coiled snake.

Snakes also resembled three other important life-affirming images: the meander of rivers, the roots of trees and plants, and the umbilical cord of mammals. There can be no structure that better symbolizes the idea of a mother/nurturer than an umbilical cord. Its form resembles two snakes entwined about each other. Rising out from a placenta’s sinuous blood vessels, the umbilical cord might easily inspire the notion that snakes were vital to life.* Further, snakes live in deep crevices and fissures in the earth, tying them to the Great Mother. And, because a snake regularly sheds its skin to begin anew, it can easily be imagined as an immortal creature that does not die, and is thus a potent symbol of rebirth. The ouroboros, the snake forming a circle to bite its own tail, was a recurrent theme in Neolithic art and occurs in almost all early cultures. Many archaeologists believe that this symbol represents the cyclical constancy of the feminine. Snakes’ association with vitality is so embedded in our psyches that the caduceus—two entwined snakes—remains as the symbol of the healing art.

Finally, the snake is associated with wisdom. Its eye is the opening to mystic insight and foresight. So connected in the Egyptian psyche were beneficent serpents and goddesses that the hieroglyph for goddess was the same as the one for serpent. The uraeus, the coiled cobra atop every pharaoh’s headdress, was the crowning symbol of Egyptian royal power.

By the time of the Middle Kingdom (2040–1600 B.C.), when literacy became more firmly established, several masculine-based creation myths rapidly gained in popularity alongside the feminine-based ones, which conjoined scales and feathers. Gradually a single god began to differentiate away from the others. Amon began his divine career as a local deity of Thebes. As Thebes grew in stature, Amon began to arrogate the power of Ra, the sun god, to become Amon-Ra, a god who could manifest his solar identity in the form of a ram-headed human. During Amon’s ascent, female deities continued to exercise jurisdiction in their respective domains, but they were steadily losing their preeminence.

During the transition from the Early Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom, Egyptian society remained rooted in agriculture. Fellahs tilled the rich delta loam and brought their produce to market as they still do today. The system of government remained a hereditary kingship balanced by a feudal aristocracy. Despite the constancy of the society’s economic and political systems, the gender of its principal deities shifted. The only truly revolutionary innovation that occurred during this period was the invention and increasing importance of written communication.*

A creation story illustrating the rise of masculine power is the one concerning Atum. As Creator, Atum masturbated into existence the Ennead, a family of eight potent gods and goddesses. Fifteen hundred years after the Nekhbet/Wadjet story of two females intertwining to bring forth life, Atum manages the task single-handedly.

Each of the nine members of the Ennead (Atum plus the other eight) represented an important force of nature. Two of them, Nut, the sky goddess, and Geb, the earth god, mated to create the physical world and all its inhabitants. Nut and Geb went on to produce three important offspring. Isis, their daughter, became Egypt’s principal fertility goddess. She was the rich black soil that lined the sacred river, and Egyptians believed she taught them the art of agriculture. Her brother, the river deity Osiris, became both her lover and her husband. The third, Seth, was in some traditions an evil brother who was jealous of Osiris. Osiris was handsome, virile and admired by all. Seth murdered Osiris in his prime, hacked his corpse to pieces, and hid the parts. Isis, tearing at her hair and scratching her face, searched for his remains. After many trials, she located them in the east. She bore his remains back to Egypt in a chartered boat, and then brought him back to life, establishing her reputation as the goddess who can resurrect both life and the land. In this myth, feminine love conquered masculine death.

Osiris’s rebirth occurred in the spring, and Egypt celebrated this miracle as its most important religious ceremony. But each fall he had to return to the netherworld. Osiris died again and again, and during the dark segment of his annual passage, he ruled as Lord of the Dead.

Isis nurturing Horus

Amidst this triumph and tragedy, and (in one version of the myth) without the aid of male insemination, Isis gave birth to her son, Horus. The many statues of Isis nursing her infant son presaged by many centuries the tender love evident between the Madonna and her infant Jesus. As mortals’ closest relative, Horus was the intermediary between ordinary humans and the divine. By claiming to be the incarnation of Horus, pharaohs legitimized their right to rule.

These gods and goddesses supplied the foundation for Egyptian religion for the first fifteen hundred years of its dynastic tradition. While Isis and Osiris occupy center stage in the wall paintings, the solitary Amon gradually accumulated power in the written texts. Then sometime between 1700 and 1550 B.C. significant changes occurred in Egyptian culture.

After several millennia of pharonic civilization, a mysterious group of invaders swept into or infiltrated the valley from the east and wrested control of the eastern part of the kingdom. For the first time in Egypt’s history, foreigners ruled the natives. Most experts identify these hated kings, known as the Hyksos, as northern Semitic Canaanites. It is likely that the Hyksos knew cuneiform. Writing had been in existence for fifteen hundred years in Mesopotamia, and conquerors boring in from this direction would have been familiar with it.*

After little more than a century, the Egyptians drove out the Hyksos, and beginning in the seventeenth century B.C., were once again in control. During the Hyksos interregnum, however, the foreigners surely exposed the Egyptians to ideas they brought from Mesopotamia. During the New Kingdom (1550-700 B.C.) that followed the expulsion of the Hyksos, Egyptian arts and architecture broke out from the conservative conventions that had typified old pre-Hyksos Egypt. Great military pharaohs such as Thutmose I, Thutmose III, and Ramses II extended Egyptian influence far beyond the eastern and southern borders of the Nile River Valley. These pharaohs commemorated their reigns with magnificent monuments.

All these dramatic changes occurring in the New Kingdom coincided with a major change in the Egyptians’ style of writing. In a trend that accelerated after the overthrow of the Hyksos, scribes increasingly used an older alternative form called hieratic script, which began to supplant hieroglyphics. Nearly abandoning the iconic principle of classical hieroglyphs, hieratic relied on the principle of phonetic pronunciation. Aesthetic considerations no longer influenced the arrangement of written characters. Earlier scribes sometimes arranged hieratic vertically but New Kingdom scribes wrote the script horizontally. Scribes also converted the glyphs representing the uniconsonants into abstract letters. Although this step presaged a true alphabet, they inexplicably did not advance to the next obvious step, which would have been to jettison everything else and keep only the abstract letters.

During the period in which a linear and abstract hieratic gained over the classical Egyptian iconic script, the culture experienced a rise in patriarchy. At the outset of the New Kingdom, Thutmose III (1490-1436 B.C.) elevated Amon’s status above all other deities by decree.* Prior to Amon, most Egyptian gods and goddesses were chimeras with both animal and human characteristics. In the New Kingdom, deities increasingly assumed human form. In a significant departure from Egyptian convention, one of Amon’s manifestations was invisible. That is, he didn’t have an image. Amon became the god-with-no-face at the moment Egyptian writing passed from icons based on images to symbols based on abstraction.

During the same period, Egypt’s principal female deities also experienced a reordering. In the earlier dynasties, Nekhbet, Wadjet, Nut, or Hathor, had been paramount. Half-human and half-vulture, cobra, sky, or cow, these early goddesses were the protectresses of birth, children, and fecundity. Isis, the principal goddess of the next generation, was more a consort, wife, mother, sister, and lover. Her most distinguishing characteristics were sexuality, fertility, and maternity. Nature personified, she also embodied the theme of resurrection.

In the New Kingdom, priests elevated a previously obscure goddess to a superior position over all the others, but in a departure from tradition as startling as the ascension of an imageless god, she was completely divorced from nature: her name was Maat and she represented Truth. Like Amon, Maat originally had been a minor fertility and nature deity. She did not reach the zenith of her sway over people until Amon lost his face. Her physical form then became human, and her symbol was an ostrich feather. In another departure, she was not a god’s lover: instead of sexuality and fecundity, she personified the abstractions of law, truth, order, and justice. When a man died, his heart was weighed on one side of the scales of justice, with Maat’s ostrich feather on the other. If the deceased had led a righteous life, the scales balanced. Occasionally, Maat was represented in the form of a hermaphrodite. Despite Maat’s rise among the literati of the court, the largely illiterate people continued to revere Isis and eagerly anticipated her compelling act of resurrection each spring.

Against this backdrop, a strange perturbation occurred in the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom, when a most unusual person became pharaoh. Amenhotep IV inherited the throne on a fluke of genetic roulette. Sickly as a child and disfigured as an adult, this teenager who ascended to high office eschewed the usual pharaonic pastime of hunting and cared little about the strategy of war or politics. He held court with his beautiful wife, Nefertiti. His two passions were reforming Egypt’s religion and its writing system.

The young regent was contemptuous of the worship of Amon. Excess power and wealth had accrued to temple priests. Spurning the advice of his counselors, he set about dismantling the trappings of the encrusted Egyptian pantheon. He declared that his subjects should worship only Aton, an obscure god, whom Amenhotep IV himself had elevated to be the Supreme Being. Like his rival Amon, Aton also had no image. But unlike Amon, Aton was so sublime and potent that he was all that there was.

Wishing to make a clean break with tradition, Amenhotep IV renamed himself Akhenaton, in deference to his newly conjured Supreme Being. He then made it a crime for anyone in the kingdom to worship the old deities. But in a telling concession, Akhenaton revealed to the people that Aton had chosen Maat to be his consort. Many historians have hailed Akhenaton as the first monotheist. Even though Maat lacked the fleshy buttocks of a Neolithic Goddess figure and she personified abstract principles, she was, nevertheless, a complementary feminine principle operating within a supposedly masculine monotheistic system. Maat’s presence in the service of Aton invalidates the claim that Akhenaton was history’s first monotheist.*

The entrenched Egyptian priesthood chafed under Akhenaton’s fiats. The young pharaoh’s decrees were decried by many as heresy. To further his reformation, Akhenaton forbade artists from making any images of Aton and in related edicts he ordered that scribes use the simplified non-iconic hieratic form of writing promoting the use of a new variant, what Egyptologists would later call the Late Egyptian.5 There is evidence that his new religion met resistance—wall paintings portray armed guards increasingly surrounding him, presumably to protect him.6

Unfortunately, Akhenaton had not completely thought through all the ramifications of his new religion. He had banished by edict both Isis’s presence and Osiris’s Land of the Dead from ordinary citizens’ lives. Rich cultic rites and beliefs, refined over many centuries, disappeared almost overnight. Akhenaton had not invented a mythology to accompany the worship of Aton. Also, since hieroglyphs were dependent on images, Akhenaton confronted the first of many problems his spare reform had raised: If Aton did not have an image, how were the folk to worship him? Akhenaton conceded that artists could portray this faceless, featureless god as an empty circle representing the solar disk with rays streaming down.*

Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and their daughter worship Aton.

The people grumbled. Gone were the pomp, circumstance, and imagery associated with the older myths. All that remained was a stiff offering to an empty sun disk and a hymn of praise written in the spare new hieratic script. Religious art, the traditional outlet for creativity, was dammed up by the severe and restrictive new state religion. Perhaps for this reason, other arts flourished. The Eighteenth Dynasty was the only period in ancient Egypt’s long history when art departed from the rigid conventions of its more familiar angular style. The royal couple commissioned many portraits of themselves and their family in attitudes of repose and worship. The fluid lines of these paintings and sculptures are sinuous and lively.

In 1908, archaeologists discovered at Tel el Amarna a large cache of ancient correspondence pertaining to Akhenaton’s reign. Satraps, loyal to Akhenaton and ruling for him on the edges of Egypt’s eastern empire, wrote the pharaoh imploring him to send military aid to help them keep Egypt’s enemies at bay. The consternation evident in the tone of these letters indicates that Akhenaton did not respond to their pleas. The Tel el Amarna letters graphically depict Egypt as a headless giant stumbling toward a fall. After ruling repressively for seventeen years, Akhenaton died and the scepter passed to Tutankhamen, a pharaoh of questionable parentage. Pressed by dissident advisers, the youth ordered the entire apparatus of Aton’s worship dismantled and Amon reinstated.

A comparison of Mesopotamia and Egypt, two neighboring civilizations that invented the written word nearly simultaneously, affords a unique opportunity to test the hypothesis of this book. Despite their geographic proximity, these two first civilizations’ attitudes toward women were as widely divergent as were their forms of writing.

The Egyptians had many joyous festivals and created the first truly erotic art. Pictures of startling anatomical accuracy have been unearthed in some temples and crypts. On occasion, they even supplied the deceased with sexual aids to enliven their afterlife.7 Their religion was based more on magic and pageantry than on obligation and morality. Premarital customs were free and easy compared to those of the Mesopotamians. Their gods were plentiful and their images, half-animal and half-human, appeared everywhere. While Amon and Aton were the chief deities among the priests and aristocracy, the common people preferred Isis, the Great Mother. Isis was not a goddess of war, and Osiris was not a warrior but rather a victim.* There is no Egyptian counterpart to the matricidal Marduk story.

While women in Mesopotamia progressively lost power, they maintained their high position in ancient Egypt. The historian Max Mueller commented, “No people ancient or modern has given women so high a legal status as did the inhabitants of the Nile Valley.”8 Wall paintings depict unself-conscious women eating and drinking in public, strolling the streets unattended, and freely engaging in industry and trade. Classical Greek historians who visited Egypt commented upon the extraordinary power Egyptian wives exerted over their husbands.*

Among royalty, Egyptian men married their sisters, not because familiarity had heightened romance, but because they desired to partake in their family’s inheritance—which in many instances passed from mother to daughter.9 The words brother and sister in Egyptian have the same significance as lover and beloved

In courtship, women often took the initiative, and in the majority of Egyptian love poems and letters the woman addresses the man. She suggests assignations, she presses her suit, and she is the one to propose marriage.10

The Mesopotamians excelled in war, laws, cruelty, science, morality, conquest, commerce, and abstract concepts. They made it a law that sons honor their fathers. Sensuality, gaiety, and respect for motherhood were more often Egypt’s chief characteristics. The Egyptians were notable for their pictorial arts, sculpture, and architecture. In general, the Babylonians hammered swords in their foundries and the Egyptians turned out exquisite jewelry in theirs. The Mesopotamian Ishtar was the goddess of strife and sexuality; Isis was maternal, loving, and fertile. Marduk was harsh and remote; the polytheistic menagerie of the Egyptians was intimate and fanciful. Women began the descent into servitude in Mesopotamia; Egyptian women maintained the highest status in the entire historical West.

LEFT: Loving Egyptain family

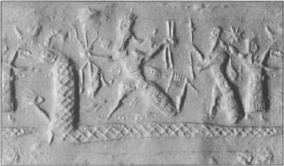

BELOW: Marduk pursues Tiamat before mutilating her.

What could account for these diametrically opposing differences? While there are many possible answers, one clear distinction between the two cultures was their form of writing: the Mesopotamians invented abstract, linearly placed wedges; the Egyptians evolved a form of script dependent on concrete, simultaneously perceived images. These choices, I propose, in turn profoundly affected the thinking processes of each culture.

Egyptian women fared better than their sisters in Mesopotamia. Nevertheless, as Egypt’s literacy rate increased, feminine authority suffered a decline. In every society that learned the written word, the female deity lost ground to the male deity. Before the invention of writing, these two powerful forces had remained entwined in sexual union. In every Mediterranean society that embraced literacy, women lost their hold and fell from grace— economically, politically, and spiritually. Writing was a gift eagerly accepted by the ancients. Unfortunately, hiding among the neat rows of carefully incised script was an unwelcome demon—misogyny. In trying to understand what went wrong between the sexes, these two cultures are at the pivot of history.

The perceptions of anyone who learned how to send and receive information by means of regular, sequential, linear rows of abstract symbols were wrenched from a balanced, centrist position toward the dominating, masculine side of the human psyche. This radical shift produced a revolution in gender relationships that was so subtle and insidious that no one noticed what was happening. But the writing styles that had been introduced so far were only hieroglyphs and cuneiform. The most dramatic changes for women were yet to come; the coming storm was brewing in the lands between Mesopotamia and Egypt.

*Confirming that two entwined snakes are the perfect image to represent life, in 1953 James Watson and Francis Crick discovered DNA’s configuration to be a double helix, the crucial molecule basic to all life.

*Even though the Egyptian icon-based system remained more right-brained than the Mesopotamians’ cuneiform, I maintain that any written method of communication skews society toward masculine values.

*Yet little in the way of a written record has come down from them. It is likely that they left one, but it would not be surprising if the Egyptians had destroyed such reminders of this ignominious chapter in their history.

*At the time of Amon’s ascent, Egypt’s empire was expanding. Local gods no longer sufficed to satisfy Egypt’s enlarging national ego.

*Late in Akhenaton’s reign, he ordered the erasure of Maat’s icon from temple walls and stelae, leaving only her name spelled phonetically.

*At the end of each ray was a small hand holding the “ankh,” the Egyptian symbol for life which Western culture adopted as the symbol for a female.

*The lioness-headed goddess Sekhmet was a goddess of war but she was minor compared to Isis.

*The Greek tourist Diodorus Siculus reported in the second century B.C. that Egyptian husbands had to promise obedience to their wives at the time of marriage vows.