30

August 27

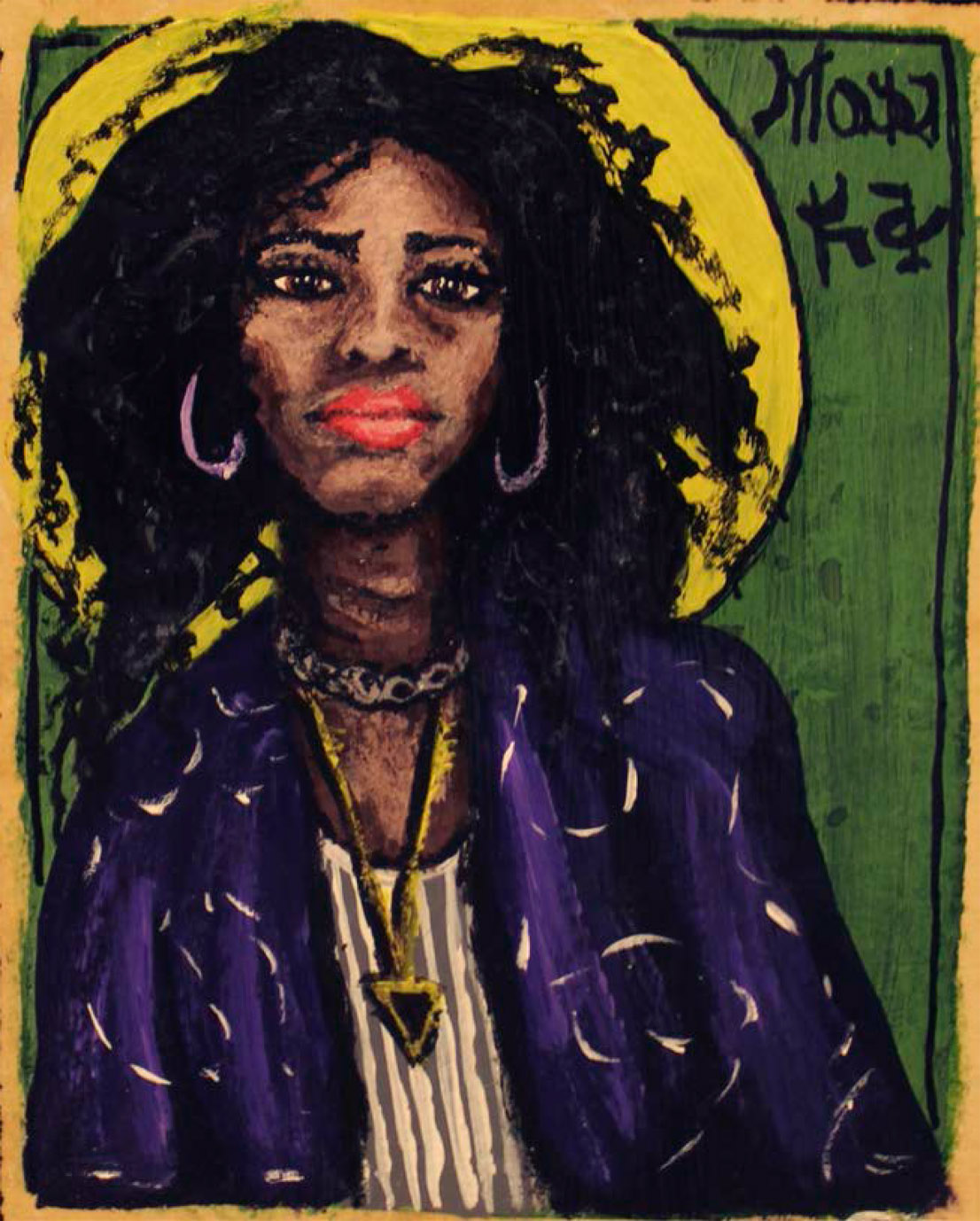

SAINT MONICA

Monica was the mother of the great North African theologian Augustine. She is the patron saint of mothers, alcoholics, conversion, and married women. The biographies say she was married to a pagan man against her will and that he was adulterous and violent. Her mother-in-law was also cantankerous, and Monica felt lonely in her family as the sole Christian. She was a virtuous woman and pestered her nonbelieving family with her piety. Eventually, though, she wore them down, and both her husband and mother-in-law converted.

She had three children who survived infancy. We don’t hear much about the other two kids and, truth be told, if Augustine hadn’t written Confessions—his doxological autobiography, still so devoutly read today—we wouldn’t know anything of Monica either. She is only known in connection to her famous son, her sainthood conferred in connection to his brilliance.

I first stumbled across Monica in a private Catholic Facebook group when a woman posted: “Please pray for my son to open his heart to Jesus again and come back to the church.” In the thread that followed, others replied, “Amen,” and “Saint Monica, pray for us!” and “For my husband as well.” Someone posted a meme of a woman in a white robe staring piously up to the sky, a young man holding her hand and matching her gaze to the heavens. Across the image it read: “Behind a great man is persistent prayers of a mother for her son’s great conversion.”

Monica is indeed credited with converting Augustine to Christianity. While her son is off rollicking in hedonism and glibly praying, “O Lord, make me chaste, but not yet,” Monica is stalking him across the Roman empire, prostrating herself at shrines and shedding buckets of tears. Augustine rebuffs her many times over. A bishop tells her, “The child of those tears shall never perish,” which gives her the encouragement to keep going. Finally, after seventeen years of Monica’s persistent prayer, Augustine is baptized into the church.

Monica reminds me of those unequally yoked books, which put the onus on Christian women to win their nonbelieving husbands back to Christ. They reference 1 Peter 3:1-2, which instructs women married to unbelievers to be persistent in good deeds so that their husbands might return to God. Why travel to a different country, these books assert, when one can be a missionary in one’s own home?

After Augustine’s hard-won conversion, Monica says she has no further earthly desires. Terrible husband? Converted. Terrible mother-in-law? Converted. Licentious son? Converted. Now, her life’s purpose is over. Handily enough, she is dead a few months later.

At first I didn’t like Monica all that much. Maybe it’s that I see myself in Monica—the deep sorrow, the desire for my husband to join me at church, the tendency to focus on other people’s faith rather than my own. There is so much crying in Monica’s story that rivers and streams are named after her tears. I imagine her clutching a hankie, hunched over at shrines, sobbing out petitions that God reach her beloved son. She is a spectacle, a caricature of the sacrificial woman, always concerned about the souls of others. When her son keeps ditching her, I want to take her by the shoulders and give a little shake, asking, “But what about your soul?”

It’s not wrong to pray for someone’s salvation, and I welcome any intercessions for Josh or me. But I am suspicious of Monica’s persistence, her patience, and her relentless prayers. I am not so sure that’s how conversion works, that the only missing ingredient from the lives of rapidly disaffiliating nones is a trusty rapid-fire prayer warrior behind the scenes. I know that my in-laws pray for Josh’s conversion every day and that he is as uninterested in Jesus as ever.

“Give it time,” the church ladies tell me, pulling me aside. “Josh might come around.” I don’t tell them that it feels dangerous to pray for his conversion outright, that I don’t want to foster false hope. I don’t want to be a missionary in my own home.

At Calvary, I imagine Saint Monica in the pew beside me with her box of Kleenex. The pastor invites people to offer a “praise, pain, or protest” to God while the offering plates are passed around. People stand up to share prayer concerns, and together we listen to a man describe his cancer treatments, to a woman’s concern for her teenage son. Afterward, we stand and sing the doxology. When the whole congregation pauses for a moment of silent prayer, I see tears tumble down Monica’s cheeks.

“Listen to your heartbeat,” the pastor says. “Stand before God and quiet yourself. Offer up your own praise, pain, or protest. Call out for God to be God.”

I squeeze my eyes shut, blocking Monica from my peripheral vision. In the silence, we stand side-by-side in God’s presence. As she sniffles, I wipe away my own tears. How embarrassing.

In the Catholic tradition, people ask the saints in heaven to pray for them. They believe that saints, though long dead, are still interceding in that great cloud of witnesses that surround us all. This practice raises my Protestant hackles, but as I stand there with Saint Monica, I kind of get it.

It’s clear that I don’t always know how to pray for this—for Josh, for his faith, our faith—but I can ask Monica if she will. As we stand together, runny-eyed, she reaches over to squeeze my hand. I am grateful that she is at my side, crying in church with me and praying for us all.