PREFACE TO THE 2021 EDITION

At the end of 2018, as I finished writing Not Working, I had no clue there was a deadly virus lurking and that a potential new Great Depression was about to hit. In the book, I note that GDP growth in the United Kingdom in the years after the Great Recession starting in 2008 was the third-slowest ever, following the South Sea Bubble financial crash three hundred years earlier, and the slowest recovery of all six hundred years ago in the aftermath of the Black Death—an unfortunate analogy, of course.

In 2020, as economies closed in March, output dropped further and more quickly than it did in the Great Recession. In the second quarter, GDP dropped 20 percent in the UK, versus 6 percent between the second quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009. In most economies the drop was much bigger than in the Great Recession: 9 percent versus 3 percent in the United States, 14 percent versus 4 percent in France, with similar stories in most other places. In the United States, as individual states opened up too soon and had to reimpose restrictions, recovery started and then slowed. At the time of writing, just after the presidential election in November 2020, a third and higher wave has emerged. The good news is that three vaccines appear to be effective and are headed apace for widespread distribution, with the vulnerable, the old, and health care workers rightly first in line.

The major lessons now are not from the Great Crash or the Great Depression but from the Great Influenza. John M. Barry’s book The Great Influenza has become the go-to source. The biggest lesson he drew from the Spanish flu (which did not start in Spain) is that authorities should tell the truth. The tapes from Bob Woodward’s 2020 book, Rage, show that the president of the United States kept the truth about the virus from the American people, presumably with serious consequences.

In the United States and the UK in particular, the unemployment rate fell below 5 percent in 2018. In the past this would have indicated an uptick in wage growth, signaling what I explain in the book as the concept of full employment. That didn’t happen. In the book, you’ll see how both countries were nowhere near full employment. Underemployment, in which workers cannot get enough hours, keeps pay in check, was high. Sadly, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s estimates of full employment were wrong. Between 2015 and 2018, anticipating inflation from raising wages, it raised interest rates. In August 2020, at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference, Chairman Jay Powell had to backtrack and shift the Fed’s inflation goal to keep rates lower for longer. He explained why as follows:

The historically strong labor market did not trigger a significant rise in inflation…. Inflation forecasts are typically predicated on estimates of the natural rate of unemployment, or “u-star,” and of how much upward pressure on inflation arises when the unemployment rate falls relative to u-star. As the unemployment rate moved lower and inflation remained muted, estimates of u-star were revised down. For example, the median estimate from FOMC [Federal Open Market Committee] participants declined from 5.5 percent in 2012 to 4.1 percent at present. The muted responsiveness of inflation to labor market tightness, which we refer to as the flattening of the Phillips curve, also contributed to low inflation outcomes.1

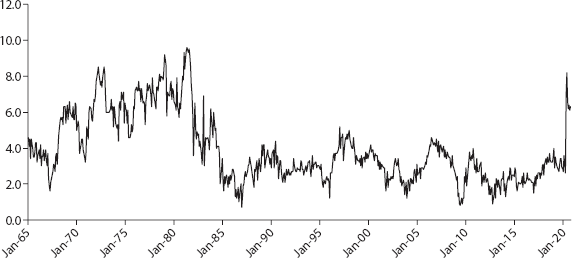

Had the new strategy been adopted five years earlier, the Fed would have delayed rate increases that began in late 2015. As I argue in the book, even then, its estimates of “u-star” (what I call the “NAIRU”) were too high, at 4.1 percent. Figure P.1 shows that during 2019, even as the unemployment rate fell to 3.5 percent at the start of 2020, weekly wage growth of average workers slowed. The Phillips curve, which you’ll learn about in the book, was flat as Kansas. The Fed’s error of raising rates too early made the American people more vulnerable to the COVID shock than they should have been. Fed errors are what commonly end recoveries. After April 2020, wage growth went strongly positive—because those who were making the lowest wages became unemployed and dropped out of the distribution.2 This may well also be occurring in the UK where Average Weekly Earnings single month annual growth went negative from April to July 2020, but the following two months returned to positive.

That isn’t the end of it. On September 16, 2020, members of the FOMC published their median projections for unemployment of 5.5 percent in 2021, 4.6 percent in 2022, and 4.0 percent in 2023. More important, they provided their estimate of the long-term unemployment rate, or the NAIRU, of 4.1 percent. The unemployment rate was below 4 percent for nineteen of the twenty months from July 2018 to February 2020 as wage growth slowed. Here we go again, more errors. This looks supremely optimistic, to say the least at a time when no fiscal stimulus package has been implemented by Congress and the FOMC has few arrows in its quiver. The FOMC has given up on serious forecasting and is just living in hopes. The right answer to where economies are headed should start with “it depends”—on how quickly a vaccine can be distributed, economic stimulus, and changes in behavior. My big hope is that labor economist Janet Yellen, who has been nominated to be the next Treasury Secretary, will deliver stimulus focused on those who need it at the low end of the income distribution.

P.1. Weekly wage growth of private sector production and non-supervisory workers in the United States, January 1965-May 2020. The Y axis refers to annual wage growth percentage. Source: The Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Pain and Distress

Even before 2020, Americans were in pain.3 The CDC analyzed the 2016 National Health Interview Survey and estimated that 50 million U.S. adults were in chronic pain.4 Pain was more prevalent among adults living in poverty, adults with less than a high school education, and adults without health insurance. Case, Deaton, and Stone (2020) have recently shown “pain prevalence rising with age until the late fifties and falling thereafter, with some leveling off after age 70.”

In new work, my colleague Andrew Oswald and I have looked at data on distress and despair in over eight million Americans. We found that, even before the pandemic hit, the proportion of people saying that all thirty of the past thirty days were bad mental health days nearly doubled from 3.6 percent in 1993 to 6.4 percent in 2019. Of particular concern is that among the white prime age (35-54) with no college education, 14 percent said this in 2019. This is precisely the group that has had disproportionately high rates of deaths of despair—from suicide, and drug and alcohol poisoning. We also found that a decline in the percentage of manufacturing employment, which has been on a steady march downward since its peak of 39.8 percent in 1944 to 8.6 percent in August 2020 (up a little from 8.5 percent at the start of 2017), has raised whites’ levels of distress and despair but has had no impact on non-whites. In 2021 and beyond, distress is inevitably going to worsen, especially for the most vulnerable, for all races.

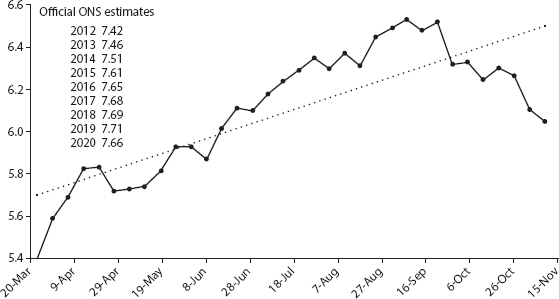

Unlike the Great Pandemic, which has seen an unprecedented collapse in well-being, the Great Recession did not generally reduce happiness. Now, however, happiness around the world has tumbled—even the quality of sleep has declined.5 Figure P.2 shows the results of a weekly survey conducted in the UK by researchers at University College London using the following question on life satisfaction, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays, where nought is ‘not at all satisfied’ and 10 is ‘completely satisfied.” This question had been asked in official surveys for several years.6 Between 2017 and 2020, it averaged 7.7. At the beginning of March 2020, researchers started collecting data and found that the average had fallen through the floor, to a never-before-seen low of 5.4. In happiness data, I had never seen anything on this scale before. By the beginning of September, as people adapted to being under lockdown, life satisfaction had steadily risen to 6.5. After that, life satisfaction fell back as the virus surged once again, falling to 6.0 at the start of November 2020.

P.2. Life satisfaction in the UK during the COVID pandemic. The data series starts in March 2020. The source of this data is The COVID-19 Social Study from University College London, https://www.covidsocialstudy.org/results

The Economics of Walking About—the Internet

In the book, I develop the idea of the “economics of walking about,” that is, trying to look at the world; listening to what people say and taking it seriously; and watching what people, firms, and governments do. But given lockdowns and not much walking about, and also because many statistical agencies closed down in the lockdown and their researchers stayed home, it has become more about the “economics of walking about the Internet.” Economists and market commentators have come up with clever ways to work out what has been going on using numerous clever examples of what I would call EWAI. This included tracking smartphone data on where people were going, Transportation Security Administration passenger data, New York City subway usage data, bookings on Grub Hub, drug prescription data, and much more. Data from the Open Table network for the numbers of seated diners at restaurants have been especially useful in showing a total collapse around the world—essentially to zero in March and April. At the time of writing at the start of November 2020 the index was still at 38 percent of its pre-pandemic levels in the United States (https://www.opentable.com/state-of-industry).

In 2020, Dhaval, Friedson, McNichols, and Sabia used cell phone data to examine the impact of the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, which brought around half a million participants to South Dakota. They used anonymized data from SafeGraph and found that counties that contributed the highest inflows of rally attendees experienced a 7.0 to 12.5 percent increase in COVID-19 cases relative to counties that did not contribute inflows. For the state of South Dakota as a whole they found the Sturgis event increased COVID-19 cases by over 35 percent. In response, the governor of South Dakota, Kristi Noem, who permitted the rally to go ahead without masks, tweeted: “This report isn’t science. It’s fiction. Under the guise of academic research, it’s nothing short of an attack on those who exercised their personal freedom to attend Sturgis.” On November 27, 2020, South Dakota had the highest death rate over the previous seven days at 2.3 per 100,000 population, of any US state, with North Dakota in second place at 1.9. Evidence hurts.

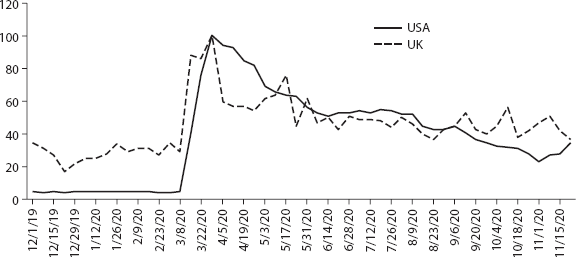

EWAI is helpful in working out what is going on with unemployment. Figure P.3 is a graph showing searches for the word “unemployment” on Google Trends in the United Kingdom and the United States. Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the graph for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. The figure shows that in both countries, searches rose sharply in March 2020, just as the happiness data collapsed, and then fell back from April through August. Second, searches ticked up in the United States from the start of November. The COVID rise in unemployment, just like the change in well-being, is much larger in the Great Pandemic than during the Great Recession.

In the UK, the Office of National Statistics asked respondents between September 16 and 20, 2020, how difficult it had been before the coronavirus pandemic for them to pay their usual household bills; 7 percent said “difficult” or “very difficult.” When asked since the pandemic, 16 percent said this. When asked if their household could afford to pay an unexpected but necessary expense of £850, or around $1,000, 35 percent said no.7 In the UK, the Trussell Trust, which runs more than one thousand food banks, reports that nearly one hundred thousand recipients needed help with food for the first time during the lockdown. In the United States, which still awaits an additional stimulus package, too many Americans are hungry and are lining up at food distribution centers.8 In a Household Pulse Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau between October 28 and November 9, 2020, 25 million adults or 10 percent of the age 18 and over population reported that in the prior seven days “sometimes” or “often” they did not have enough to eat.

P.3. Searches for “unemployment” on Google Trends, September 2019-September 2020. A value of 100 on Google Trends means that the particular search query is highly popular and trending. Google indexes the data to 100, where 100 is the maximum search interest for the time and location selected.

The question now is, What is coming? It all depends, not least on what governments do. Will there be a second stimulus package in the United States, and if so, when and how much? Will Brexit happen? In the UK, will a furlough scheme that pays the wages of those out of work because of COVID be withdrawn as planned in October 2020?

Another major question is to what degree will people permanently change their behavior going forward? In Florida, where I go for the winter, the elderly snowbirds traditionally meet for breakfast. That custom has faded away as the elderly (like me!) stopped going out to eat and none of these restaurants do take-out breakfast. Shopping malls, cruises, movie theaters, and gyms are unlikely to return to former glories. Pandora’s box has been opened, and the movement from urban to rural is under way. House prices are surging in New England.9

An urgent concern, given how I discuss in the book that long spells of joblessness when a person is young create permanent scars, is the likely rise of youth unemployment among minorities and the less educated. The kids who left high school in the summer of 2020 have nowhere to go. David Bell and I have proposed the equivalent of the Civilian Conservation Corps, which Franklin Roosevelt introduced in the 1930s.10 It hired young, unmarried men to work on conservation and development of natural resources in rural areas. During its nine years of operation, three million young men, mainly aged eighteen to twenty-five, passed through it. Most of the jobs were manual. The CCC helped with forest management, flood control, conservation projects, and the development of state and national parks. It was credited with improving the employability, well-being, and fitness of participants. Young married men and married and unmarried women under our proposal of course would also be included, and the jobs don’t have to be manual. We must do something and soon.

It is still true that everyone wants a good job, and there are even fewer of them to go around now than when I wrote the book. Going forward it seems likely that many more people than in the past will be underemployed, with fewer hours and lower wages than they would like. Life is going to be a struggle, and hopefully there will be a vaccine, but at the time of writing we can’t predict when or how. We can predict that, as we come out of this crisis, vastly many will need to regain work and meaning in their lives. We need to understand how the labor market works and how it is central to everything—work makes people happy. That makes Not Working more important now than ever. Gizza job.

References

Bell, D.N.F., and D. G. Blanchflower. 2019. “Underemployment in Europe and the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review. November 22. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0019793919886527.

Blanchflower, D. G., and A. Bryson. 2020. “Unemployment Disrupts Sleep.” NBER Working Paper #27814.

Blanchflower, D. G., and A. J. Oswald. 2019. “Unhappiness and Pain in Modern America: A Review Essay, and Further Evidence, on Carol Graham’s Happiness for All?” Journal of Economic Literature June 57 (2): 385–402.

Blanchflower, D. G., and A. J. Oswald. 2020. 2020. “Trends in Extreme Distress in the United States, 1993–2019.” American Journal of Public Health 110 (10): 1538–44. https://doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305811.

Case, A., A. Deaton, and A. A. Stone. 2020. “Decoding the Mystery of American Pain Reveals a Warning for the Future.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (40): 24785–89. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012350117.

Dahlhamer J., J. Lucas, C. Zelaya, et al. 2018. “Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Adults—United States, 2016.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67 (36): 1001–6.

Dhaval, D., A. I. Friedson, D. McNichols, and J. J. Sabia. 2020. The Contagion Externality of a Superspreading Event: The Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and COVID-19. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Discussion Paper No. 13670.

Trussell Trust. 2020. Lockdown, Lifelines, and the Long Haul Ahead: The Impact of Covid-19 on Food Banks in the Trussell Trust Network. https://www.trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/09/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-food-banks-report.pdf.

Notes

1. Jerome Powell, “New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review,” presented at “Navigating the Decade Ahead: Implications for Monetary Policy,” an economic policy symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, WY, August 27, 2020.

2. Wage growth by month for PNSW production and non-supervisory workers with the unemployment rate adjusted for misclassification error from April in parentheses is as follows: Aug 19 = 3.1 (3.7); Sep 19 = 3.4 (3.5); Oct 19 = 3.4 (3.6); Nov 19 = 2.9 (3.5); Dec 19 = 2.9 (3.5); Jan 20 = 2.7 (3.6); Feb 20 = 3.6 (3.5); Mar 20 = 2.6 (4.4); Apr 20 = 7.0 (17.7); May 20 = 8.2 (14.3); Jun 20 = 6.6 (12.1); Jul 20 = 6.2 (11.2); Aug 20 = 6.2 (9.1); Sep 20 = 6.1 (8.3); Oct 20 = 6.3 (7.2). Usual weekly earnings from the CPS household survey were up 8.2 percent on the year in Q3 2020, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf.

3. Blanchflower and Oswald 2019.

4. Chronic pain was defined as pain on most days or every day in the past six months (Dahlhamer et al. 2018).

5. Blanchflower and Bryson 2020.

6. Thanks to Daisy Fancourt for kindly providing me with these data from the COVID-19 Social Study at University College London, https://www.covidsocialstudy.org/results.

7. Office for National Statistics, “Coronavirus and the Social Impacts on Great Britain,” https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/datasets/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritaindata.

8. Trussell Trust 2020. Jennifer Smith, “Pandemic, Growing Need Strain U.S. Food Bank Operations,” Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2020. Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, “How Hunger Persists in a Rich Country like America,” New York Times Magazine, September 2, 2020. Tim Arango, “Just because I Have a Car Doesn’t Mean I Have Enough Money to Buy Food,” New York Times, September 3, 2020.

9. Peter Cobb, “Vermont’s Land Grab: Real Estate Is a Hot Commodity in COVID Era,” Barre-Montpelier Times Argus, September 26, 2020. Glenn Jordan, “Maine House Prices up 17% as Sales to Out-of-State Buyers Increase,” Portland Press Herald, September 22, 2020.

10. David Blanchflower and David Bell, “We Must Act Now to Shield Young People from the Economic Scarring of Covid-19,” Guardian, May 22, 2020.