TOY BOOKS.

As, until recently, I suppose I was scarcely known out of the nursery, it is meet that I should offer some remarks upon children's books. Here, undoubtedly, there has been a remarkable development and great activity of late years. We all remember the little cuts that adorned the books of our childhood. The ineffaceable quality of these early pictorial and literary impressions afford the strongest plea for good art in the nursery and the schoolroom. Every child, one might say every human being, takes in more through his eyes than his ears, and I think much more advantage might be taken of this fact.

If I may be personal, let me say that my first efforts in children's books were made in association with Mr. Edmund Evans. Here, again, I was fortunate to be in association with the craft of colour-printing, and I got to understand its possibilities. The books for babies, current at that time—about 1865 to 1870—of the cheaper sort called toy books were not very inspiriting. These were generally careless and unimaginative woodcuts, very casually coloured by hand, dabs of pink and emerald green being laid on across faces and frocks with a somewhat reckless aim. There was practically no choice between such as these and cheap German highly-coloured lithographs. The only attempt at decoration I remember was a set of coloured designs to nursery rhymes by Mr. H. S. Marks, which had been originally intended for cabinet panels. Bold outlines and flat tints were used. Mr. Marks has often shown his decorative sense in book illustration and printed designs in colour, but I have not been able to obtain any for this book.

It was, however, the influence of some Japanese printed pictures given to me by a lieutenant in the navy, who had brought them home from there as curiosities, which I believe, though I drew inspiration from many sources, gave the real impulse to that treatment in strong outlines, and flat tints and solid blacks, which I adopted with variations in books of this kind from that time (about 1870) onwards. Since then I have had many rivals for the favour of the nursery constituency, notably my late friend Randolph Caldecott, and Miss Kate Greenaway, though in both cases their aim lies more in the direction of character study, and their work is more of a pictorial character than strictly decorative. The little preface heading from his "Bracebridge Hall" gives a good idea of Caldecott's style when his aim was chiefly decorative. Miss Greenaway is the most distinctly so perhaps in the treatment of some of her calendars.

RANDOLPH CALDECOTT.

|

|

(MACMILLAN, 1877.) |

KATE GREENAWAY.

|

KEY BLOCK OF TITLE-PAGE OF "MOTHER GOOSE." |

(ROUTLEDGE, N.D.) |

CHILDREN'S BOOKS.

Children's books and so-called children's books hold a peculiar position. They are attractive to designers of an imaginative tendency, for in a sober and matter-of-fact age they afford perhaps the only outlet for unrestricted flights of fancy open to the modern illustrator, who likes to revolt against "the despotism of facts." While on children's books, the poetic feeling in the designs of E. V. B. may be mentioned, and I mind me of some charming illustrations to a book of Mr. George Macdonald's, "At the Back of the North Wind," designed by Mr. Arthur Hughes, who in these and other wood engraved designs shows, no less than in his paintings, how refined and sympathetic an artist he is. Mr. Robert Bateman, too, designed some charming little woodcuts, full of poetic feeling and controlled by unusual taste. They were used in Macmillan's "Art at Home" series, though not, I believe, originally intended for it.

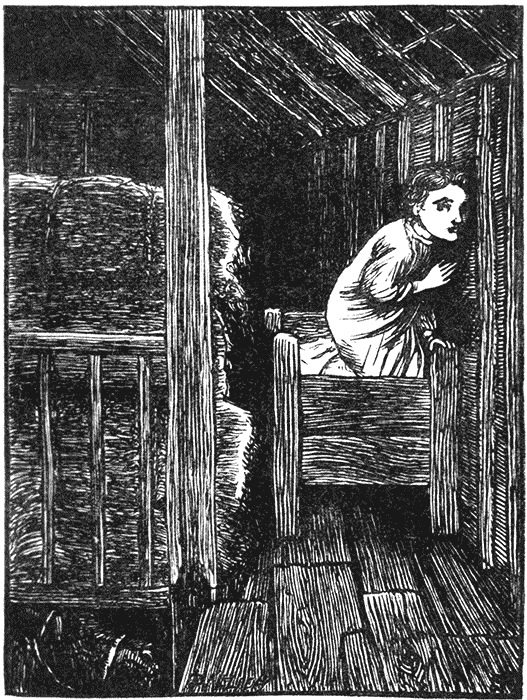

ARTHUR HUGHES.

|

FROM "AT THE BACK OF THE NORTH WIND." |

(STRAHAN, 1871.) |

JAPANESE INFLUENCE.

There is no doubt that the opening of Japanese ports to Western commerce, whatever its after effects—including its effect upon the arts of Japan itself—has had an enormous influence on European and American art. Japan is, or was, a country very much, as regards its arts and handicrafts with the exception of architecture, in the condition of a European country in the Middle Ages, with wonderfully skilled artists and craftsmen in all manner of work of the decorative kind, who were under the influence of a free and informal naturalism.JAPANESE ILLUSTRATION. Here at least was a living art, an art of the people, in which traditions and craftsmanship were unbroken, and the results full of attractive variety, quickness, and naturalistic force. What wonder that it took Western artists by storm, and that its effects have become so patent, though not always happy, ever since. We see unmistakable traces of Japanese influences, however, almost everywhere—from the Parisian impressionist painter to the Japanese fan in the corner of trade circulars, which shows it has been adopted as a stock printers' ornament. We see it in the sketchy blots and lines, and vignetted naturalistic flowers which are sometimes offered as page decorations, notably in American magazines and fashionable etchings. We have caught the vices of Japanese art certainly, even if we have assimilated some of the virtues.

ARTHUR HUGHES.

|

FROM "AT THE BACK OF THE NORTH WIND." |

(STRAHAN, 1871.) |

In the absence of any really noble architecture or substantial constructive sense, the Japanese artists are not safe guides as designers. They may be able to throw a spray of leaves or a bird or fish across a blank panel or sheet of paper, drawing them with such consummate skill and certainty that it may delude us into the belief that it is decorative design; but if an artist of less skill essays to do the like the mistake becomes obvious. Granted they have a decorative sense—the finesse which goes to the placing of a flower in a pot, of hanging a garland on a wall, or of placing a mat or a fan—taste, in short, that is a different thing from real constructive power of design, and satisfactory filling of spaces.

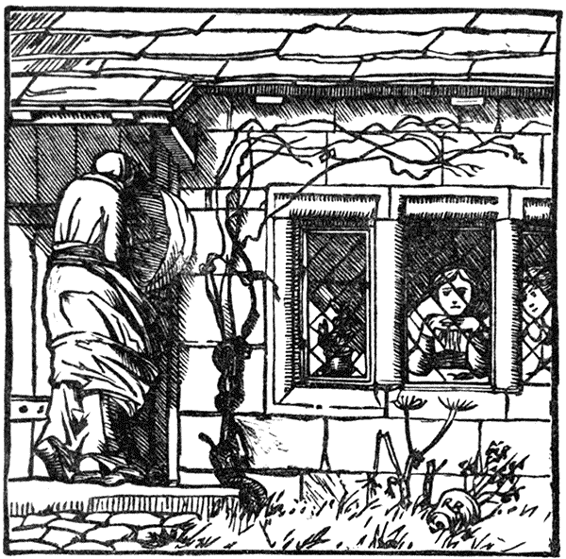

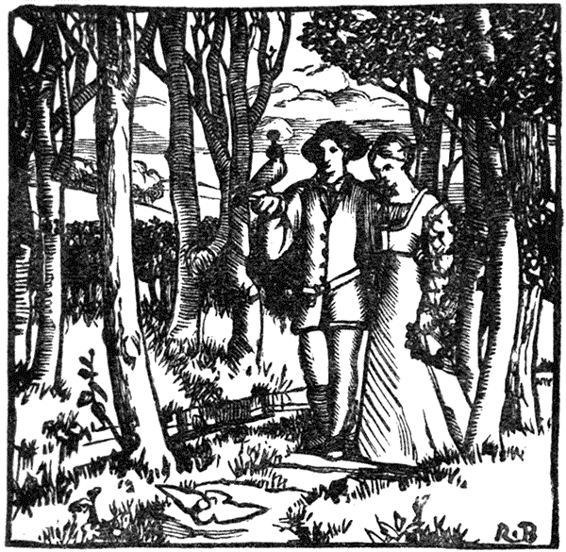

ROBERT BATEMAN.

|

FROM "ART IN THE HOUSE." |

(MACMILLAN, 1876.) |

When we come to their books, therefore, marvellous as they are, and full of beauty and suggestion—apart from their naturalism, grotesquerie, and humour—they do not furnish fine examples of page decoration as a rule. The fact that their text is written vertically, however, must be allowed for. This, indeed, converts their page into a panel, and their printed books become rather what we should consider sets of designs for decorating light panels, and extremely charming as such.

ROBERT BATEMAN.

|

FROM "ART IN THE HOUSE." |

(MACMILLAN, 1877.) |

These drawings of Hokusai's (see Nos. 10 and 11, Appendix), the most vigorous and prolific of the more modern and popular school, are striking enough and fine enough, in their own way, and the decorative sense is never absent; controlled, too, by the dark border-line, they do fill the page, which is not the case always with the flowers and birds. However, I believe these holes, blanks, and spaces to let are only tolerable in a book because the drawing where it does occur is so skilful (except where the effect is intentionally open and light); and from tolerating we grow to like them, I suppose, and take them for signs of mastery and decorative skill. In their smaller applied ornamental designs, however, the Japanese often show themselves fully aware of a systematic plan or geometric base: and there is usually some hidden geometric relation of line in some of their apparently accidental compositions. Their books of crests and pattern plans show indeed a careful study of geometric shapes, and their controlling influence in designing.

JAPANESE PRINTING.

As regards the history and use of printing, the Japanese had it from the Chinese, who invented the art of printing from wooden blocks in the sixth century. "We have no record," says Professor Douglas,[5] "as to the date when metal type was first used in China, but we find Korean books printed as early as 1317 with movable clay or wooden type, and just a century later we have a record of a fount of metal type being cast to print an [6]

ROBERT BATEMAN.

|

FROM "ART IN THE HOUSE." |

(MACMILLAN, 1876.) |

I have mentioned the American development of wood-engraving. Its application to magazine illustration seems certainly to have developed or to have

ROBERT BATEMAN.

|

FROM "ART IN THE HOUSE." |

(MACMILLAN, 1876.) |

JOSEPH PENNELL.

The admirable and delicate architectural and landscape drawings of Mr. Joseph Pennell, for instance, are well known, and, as purely illustrative work, fresh, crisp in drawing, and original in treatment, giving essential points of topography and local characteristics (with a happy if often quaint and unexpected selection of point of view, and pictorial limits), it would be difficult to find their match, but very small consideration or consciousness is shown for the page. If he will pardon my saying so, in some instances the illustrations are, or used to be, often daringly driven through the text, scattering it right and left, like the effect of a coach and four upon a flock of sheep. In some of his more recent work, notably in his bolder drawings such as those in the "Daily Chronicle," he appears to have considered the type relation much more, and shows, especially in some of his skies, a feeling for a radiating arrangement of line.

AMERICAN DRAUGHTSMEN.

Our American cousins have taught us another mode of treatment in magazine pages. It is what I have elsewhere described as the "card-basket style." A number of naturalistic sketches are thrown accidentally together, the upper ones hiding the under ones partly, and to give variety the corner is occasionally turned down. There has been a great run on this idea of late years, but I fancy it is a card trick about "played out."

However opinions may vary, I think there cannot be a doubt that in Elihu Vedder we have an instance of an American artist of great imaginative powers, and undoubtedly a designer of originality and force. This is sufficiently proved from his large work—the illustrations to the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam." Although the designs have no Persian character about them which one would have thought the poem and its imagery would naturally have suggested, yet they are a fine series, and show much decorative sense and dramatic power, and are quite modern in feeling. His designs for the cover of "The Century Magazine" show taste and decorative feeling in the combination of figures with lettering.

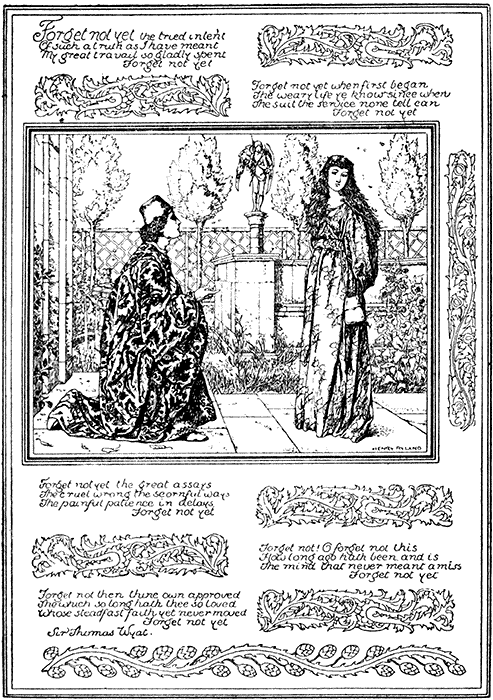

Mr. Edwin Abbey is another able artist, who has shown considerable care for his illustrated page, in some cases supplying his own lettering; though he has been growing more pictorial of late: Mr. Alfred Parsons also, though he too often seems more drawn to the picture than the decoration. Mr. Heywood Sumner shows a charming decorative sense and imaginative feeling, as well as humour. On the purely ornamental side, the accomplished decorations of Mr. Lewis Day exhibit both ornamental range and resource, which, though in general devoted to other objects, are conspicuous enough in certain admirable book and magazine covers he has designed.

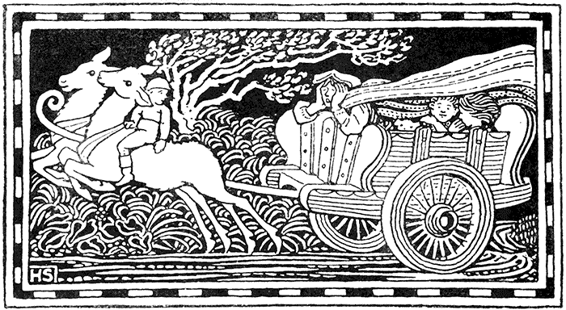

HEYWOOD SUMNER.

FROM "STORIES FOR CHILDREN," BY FRANCES M. PEARD. (ALLEN, 1896.)

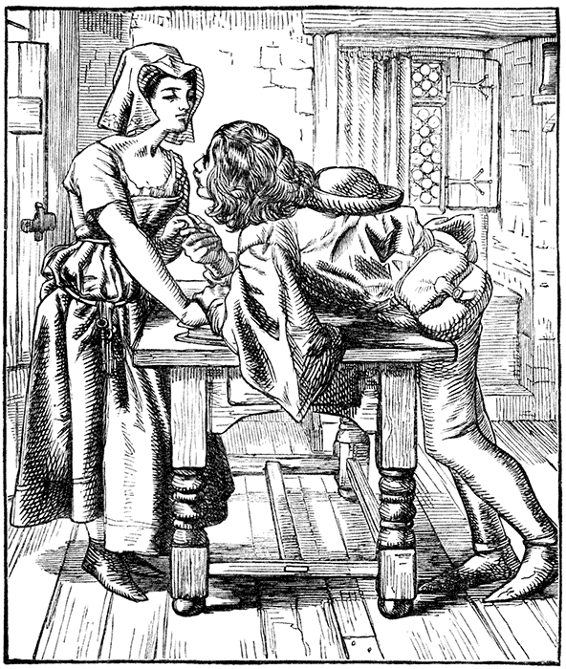

CHARLES KEENE.

ILLUSTRATION TO "THE GOOD FIGHT." ("ONCE A WEEK," 1859.)

(By permission of Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew and Co.)

HEYWOOD SUMNER.

|

FROM "STORIES FOR CHILDREN," BY F. M. PEARD. |

(ALLEN, 1896.) |

THE "ENGLISH ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE."

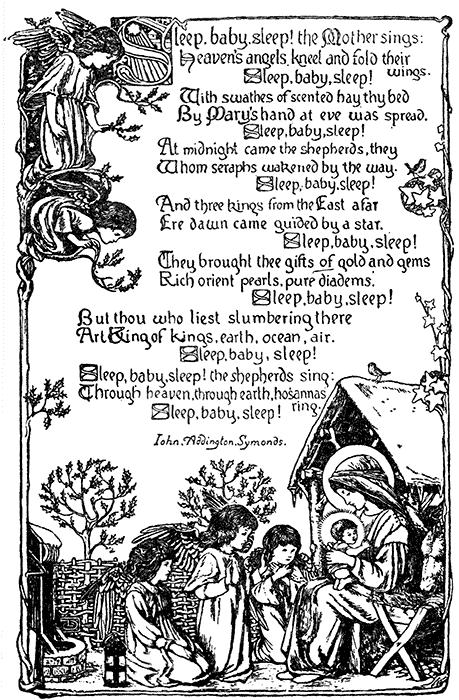

"The English Illustrated Magazine," under Mr. Comyns Carr's editorship, by its use of both old and modern headings, initials and ornaments, did something towards encouraging the taste for decorative design in books. Among the artists who designed pages therein should be named Henry Ryland and Louis Davis, both showing graceful ornamental feeling, the children of the latter artist being very charming.

LOUIS DAVIS.

FROM THE "ENGLISH ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE" (1892).

HENRY RYLAND.

FROM THE "ENGLISH ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE" (1894).

But it would need much more space to attempt to do justice to the ability of my contemporaries, especially in the purely illustrative division, than I am able to give.

"ONCE A WEEK."

The able artists of "Punch," however, from John Leech to Linley Sambourne, have done much to keep alive a vigorous style of drawing in line, which, in the case of Mr. Sambourne, is united with great invention, graphic force, and designing power. In speaking of "Punch," one ought not to forget either the important part played by "Once a Week" in introducing many first-rate artists in line. In its early days we had Charles Keene illustrating Charles Reade's "Good Fight," with much feeling for the decorative effect of the old German woodcut. Such admirable artists as M. J. Lawless and Frederick Sandys—the latter especially distinguished for his splendid line drawings in "Once a Week" and "The Cornhill;" one of his finest is here given, "The Old Chartist," which accompanied a poem by Mr. George Meredith. Indeed, it is impossible to speak too highly of Mr. Sandys' draughtsmanship and power of expression by means of line; he is one of our modern English masters who has never, I think, had justice done to him.

F. SANDYS.

|

"THE OLD CHARTIST." |

("ONCE A WEEK," 1861.) |

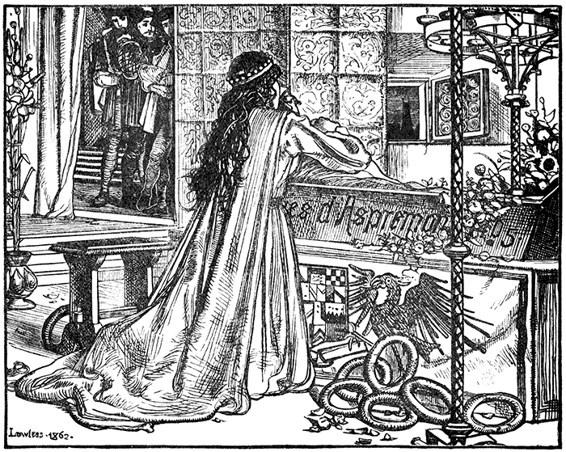

M. J. LAWLESS.

|

"DEAD LOVE." |

("ONCE A WEEK," 1862.) |

I can only just briefly allude to certain powerful and original modern designers of Germany, where indeed, the old vigorous traditions of woodcut and illustrative drawing seem to have been kept more unbroken than elsewhere.

On the purely character-drawing, pictorial and illustrative side, there is of course Menzel, thoroughly modern, realistic, and dramatic. I am thinking more perhaps of such men as Alfred Rethel, whose designs of "Death the Friend" and "Death the Enemy," two large woodcuts, are well known. I remember also a very striking series of designs of his, a kind of modern "Dance of Death," which appeared about 1848, I think. Schwind is another whose designs to folk tales are thoroughly German in spirit and imagination, and style of drawing. Oscar Pletsch, too, is remarkable for his feeling for village life and children, and many of his illustrations have been reproduced in this country. More recent evidence, and more directly in the decorative direction, of the vigour and ornamental skill of German designers, is to be found in those picturesque calendars, designed by Otto Hupp, which come from Munich, and show something very like the old feeling of Burgmair, especially in the treatment of the heraldry.

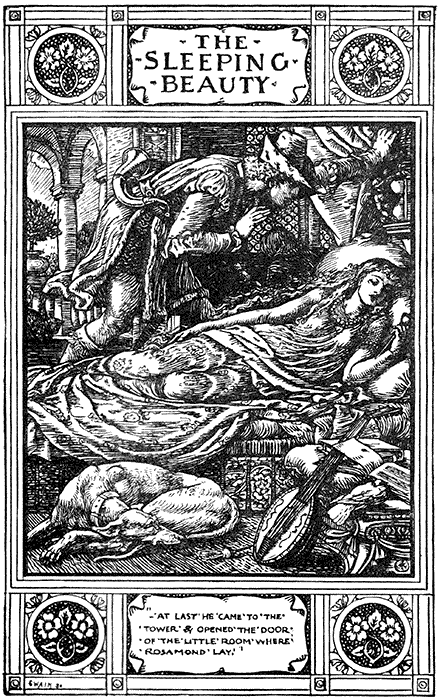

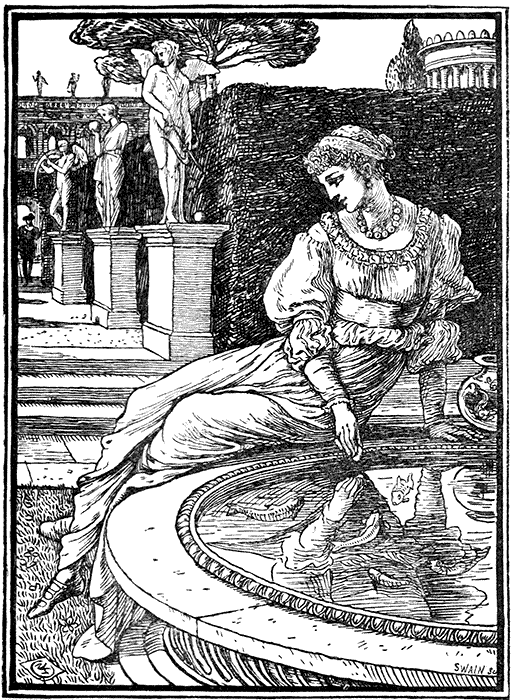

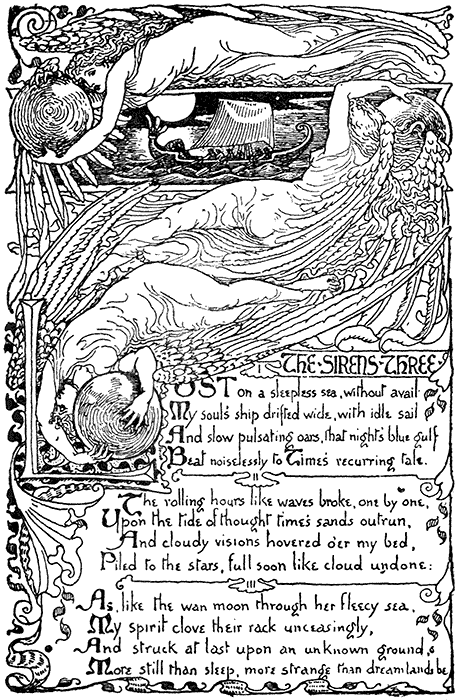

I have ventured to give a page or two here from my own books, "Grimm," "The Sirens Three," and others, which serve at least to show two very different kinds of page treatment. In the "Grimm" the picture is inclosed in formal and rectangular lines, with medallions of flowers at the four corners, the title and text being written on scrolls above and below. In "The Sirens Three" a much freer and more purely ornamental treatment is adopted, and a bolder and more open line. A third, the frontispiece of "The Necklace of Princess Fiorimonde," by Miss de Morgan, is more of a simple pictorial treatment, though strictly decorative in its scheme of line and mass.

THE INFLUENCE OF PHOTOGRAPHY.

The facile methods of photographic-automatic reproduction certainly give an opportunity to the designer to write out his own text in the character that pleases him, and that accords with his design, and so make his page a consistent whole from a decorative point of view, and I venture to think when this is done a unity of effect is gained for the page not possible in any other way.

Indeed, the photograph, with all its allied discoveries and its application to the service of the printing press, may be said to be as important a discovery in its effects on art and books as was the discovery of printing itself. It has already largely transformed the system of the production of illustrations and designs for books, magazines, and newspapers, and has certainly been the means of securing to the artist the advantage of possession of his original, while its fidelity, in the best processes, is, of course, very valuable.

Its influence, however, on artistic style and treatment has been, to my mind, of more doubtful advantage. The effect on painting is palpable enough, but so far as painting becomes photographic, the advantage is on the side of the photograph. It has led in illustrative work to the method of painting in black and white, which has taken the place very much of the use of line, and through this, and by reason of its having fostered and encouraged a different way of regarding nature—from the point of view of accidental aspect, light and shade, and tone—it has confused and deteriorated, I think, the faculty of inventive design, and the sense of ornament and line; having concentrated artistic interest on the literal realization of certain aspects of superficial facts, and instantaneous impressions instead of ideas, and the abstract treatment of form and line.

WALTER CRANE.

|

FROM GRIMM'S "HOUSEHOLD STORIES." |

(MACMILLAN, 1882.) |

WALTER CRANE.

|

FRONTISPIECE. |

"PRINCESS FIORIMONDE" |

(MACMILLAN, 1880). |

WALTER CRANE.

|

"THE SIRENS THREE" |

OPENING PAGE. |

(MACMILLAN, 1886.) |

A DECORATIVE IDEAL.

This, however, may be as much the tendency of an age as the result of photographic invention, although the influence of the photograph must count as one of the most powerful factors of that tendency. Thought and vision divide the world of art between them—our thoughts follow our vision, our vision is influenced by our thoughts. A book may be the home of both thought and vision. Speaking figuratively, in regard to book decoration, some are content with a rough shanty in the woods, and care only to get as close to nature in her more superficial aspects as they can. Others would surround their house with a garden indeed, but they demand something like an architectural plan. They would look at a frontispiece like a façade; they would take hospitable encouragement from the title-page as from a friendly inscription over the porch; they would hang a votive wreath at the dedication, and so pass on into the hall of welcome, take the author by the hand and be led by him and his artist from room to room, as page after page is turned, fairly decked and adorned with picture, and ornament, and device; and, perhaps, finding it a dwelling after his desire, the guest is content to rest in the ingle nook in the firelight of the spirit of the author or the play of fancy of the artist; and, weaving dreams in the changing lights and shadows, to forget life's rough way and the tempestuous world outside.

[3] A memoir of Edward Calvert has since been published by his son, fully illustrated, and giving the little engravings just spoken of. They were engraved by Calvert himself, it appears, and I am indebted to his son, Mr. John Calvert, for permission to print them here.

[4] A striking instance of the use of white line is seen in the title page "Pomerium de Tempore," printed by Johann Otmar, Augsburg, as early as 1502. It is possible, however, that this is a metal engraving. It is given overleaf.

[5] Guide to the Chinese and Japanese Illustrated Books in the British Museum.

[6] Satow. "History of Printing in Japan."