1

Thinking About Thinking

The next item on the agenda,” said Tom Darfield, president of Family Frozen Foods, “is adding a fifth truck to our fleet.” The three senior company officers seated at the conference table gave him their full attention. “When Marty made this proposal a few months ago, we dismissed it. But I think it’s time to discuss it again in view of our increased sales and signs that this growth will continue.”

All eyes shifted to Martin Bloomfield, who was in charge of sales and deliveries of the company’s varied lines of frozen meat and prepared foods. “I know,” he said, clearing his throat and nodding. “You’re tired of hearing this proposal, but you’ve got to admit we have more business than four trucks can handle. The last time we talked about this, our fleet was already straining to meet deliveries. You all decided it was premature to add another truck; better to wait and see how business went. Well, business is booming.”

“I agree,” said Darfield, asserting his dual role as presiding officer and final decision maker. “It’s time to reconsider Marty’s proposal.”

“The issue isn’t simply the amount of business,” interjected Dorothy Pellman, the company’s chief administrative officer, who handled budgeting, finance, and personnel matters. She fixed her eyes on Darfield. “Marty wants to buy a sixteen-wheeler. Ben and I feel a standard delivery van would be more than adequate.”

Ben Augmeyer, who managed the processing and packaging of the company’s products, leaned forward and looked at Bloomfield. “Are you still set on a semi?”

“It would be shortsighted not to be,” he replied. “Given the favorable outlook for sales, in twelve months we’ll be glad we bought the larger vehicle.”

“Which outlook are you talking about?” asked Ben.

“Last month’s forecast.”

“That forecast was flawed. As we agreed last week, those sales estimates don’t take account of seasonal variations,” said Augmeyer.

“They sure as hell do,” countered Bloomfield. “Dotty said so herself yesterday.”

Augmeyer’s expression soured as he turned to Pellman. “Since when?”

“He’s right, Ben,” she said with a rueful shrug, reluctant to lend any support to Bloomfield’s proposal. “I recomputed the data using the most recent market analysis. The trends clearly point to a regional upturn in consumer interest in our line of products. Even without increasing our advertising, the growth in sales should continue.”

“Do you believe that, Tom?”

“Sure, Ben. The trades say the same thing.”

“Then why not buy the larger truck?” declared Bloomfield.

Pellman shook her head. “Hiring a reliable, qualified driver will be a lot easier with a smaller vehicle.”

“That’s true,” added Darfield, inclining his head toward Bloomfield.

“Remember the trouble we had three years ago,” said Augmeyer, “trying to keep drivers for that huge used semi we bought? They hated it because it drove like a Sherman tank.”

“They quit because we didn’t pay them enough, not because of the truck,” argued Bloomfield. “Now we can offer competitive pay. And for what it’s worth, the new semis are easy to drive.”

“No sixteen-wheeler is easy to drive, Marty!” exclaimed Pellman.

“How would you know?” he challenged. “You’ve never driven one.”

“The main issue,” said Augmeyer, changing the subject, “is load capacity. How many times will a semi be filled to capacity or even half capacity? Dotty and I believe that a van will be adequate for most deliveries, and in those few instances when it isn’t, we can make up the shortfall with overtime.”

“And a van gets better mileage,” said Pellman, “and is easier to maintain, which means it’ll be more reliable.”

“That’s true, Marty,” said Darfield.

Marty felt beleaguered. “But you aren’t taking into consideration economies of size. One semi can do the work of three or four vans. And what about the company’s public image? Small vans connote small business; a semi with our company logo splashed across its sides says ‘big business.’ It would enhance our reputation and increase sales.”

“Maybe so,” argued Pellman, “but have you looked at what a semi costs? Three times the price of a van.”

“She has a point, Marty,” said Darfield.

“Is that right?” stated Darfield, more as a fact than a question.

“But their situations are different,” argued Bloomfield.

“We’re all in the same business, Marty,” said Darfield. “Dotty and Ben make a strong case, and we’ve got to move on to other pressing matters. I think we should go with a van.”

Why did they make the wrong decision? Where did their discussion of the proposal—of the problem—go astray? What could they have done differently? What should they have done?

The above dialogue is typical of business and professional meetings. Discussion—analysis of a problem —jumps haphazardly from one aspect to another as the conferees make points supporting their views and attacking those of others. Of course, a host of other factors also come into play to cloud the issues and defeat objective analysis, such as the differing but unstated assumptions on which the participants base their proposals to solve the problem, conflicting analytic approaches, personality differences, emotions, debating skills, the hierarchical status of the conferees within the organization, the compulsion of some members to seek to dominate and control the meeting, and so on. The cumulative result all too often is confusion, acrimony, wasted time, and ultimately flawed analysis, leading to unsatisfactory decisions.

While training people how to run a meeting and how to interact effectively in group decision making will help, the best remedy for the ineffectiveness of the meeting of the managers of Family Frozen Foods—and every other similarly afflicted meeting—is structure. By structure I mean a logical framework in which to focus discussion on key points and keep it focused, ensuring that each element, each factor, of a problem is analyzed separately, systematically, and sufficiently.

Why is imposing a structure on deliberations like those of Family Frozen Foods so important? The answer lies in the uncomfortable fact that, when it comes to problem solving, we humans tend to be poor analysts. We analyze whatever facts we have, make suppositions about those aspects for which we have no facts, conceive of a solution, and (like the managers of Family Frozen Foods) hope it solves the problem. If it doesn’t, we repeat the process until we either solve the problem or resolve to live with it. It’s the familiar trial-and-error technique. We humans therefore tend to muddle through in problem solving, enjoying moderate success, living with our failures, and trusting in better luck next time.

Wouldn’t you think, with all the breathtaking advances modern humans have made in every field of endeavor in the past couple of centuries, that we would have achieved some breakthroughs in how to analyze problems? Don’t we have marvelous new insights from cognitive science into the workings of the brain? Haven’t we created and made available to everyone computers of prodigious capability that enable us to gather, store, and manipulate information on a scale and at a speed unheard of even ten years ago? And, as a world, don’t we know more about everything than humankind has ever known before? So what’s the problem? How come we haven’t broken new ground in the way we analyze problems? How come we haven’t developed new, innovative analytic techniques? How come we haven’t adopted more effective analytic approaches? How come?

The fact is that new ground has been broken, innovative techniques have been developed, more effective approaches have been devised. Powerful, practical, proven techniques for analyzing problems of every type do exist The problem is that they are one of the world’s best-kept secrets. Even though these techniques are used with excellent effect in certain specialized professional disciplines, they have not found wide application elsewhere.

Ah, you ask, but if these techniques are so powerful, practical, and proven, why aren’t they used more widely?

There are two reasons: one is excusable, the other is not. Let me explain the inexcusable first.

Schools Don’t Teach Analytic Techniques

That’s not exactly true. Educational institutions do teach these analytic techniques, but only to a chosen few. Universities and colleges (high schools, too) treat these techniques as esoteric methods relevant only to special fields of study, not as standard analytic approaches in mainstream curricula. Thus, comparatively few college graduates (and only a handful of high school graduates) are aware of these techniques and their immense potential as aids to problem solving.

I base this statement not on any statistical survey but on my personal experience. For example, only two of the forty-eight graduate students to whom a colleague, with my assistance, taught these techniques for four semesters in Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Washington, D.C., had ever before been exposed to them—and neither had been exposed to all of the techniques. In my daily contacts, I often ask people if they are familiar with this or that technique; rare is the person who knows what I’m talking about. If you doubt the validity of this statistic, do a little data gathering yourself: ask a friend, your spouse, or a casual acquaintance if, in high school or college, he or she was ever taught any of the analytic techniques you’ll learn in this book. And don’t bother telling me their answers; I know what they’ll say.

So why do schools restrict the teaching of this knowledge? Why don’t they incorporate these analytic techniques into mainstream curricula? Why don’t they teach all students, regardless of their academic focus, how to apply these techniques to problem solving? The answer is the second—the excusable—reason why these techniques are not widely employed.

Human Beings Tend to Avoid Analytic Structure

Sometimes, when I offer to show people how to structure their analysis of problems, they say, “Sorry, but I’m awfully busy.” “No, thank you. We don’t use things like that here.” “Very interesting, but it sounds a bit arcane.” “I wouldn’t think of using such Byzantine methods.”

The rejection is so spontaneous and emphatic that it could be only a mental knee-jerk reflex, not a reasoned response. What could be causing this unreasoning reflex? Because they have not learned and understood the techniques, they could not have performed any cost-benefit analysis on them. They therefore have not assimilated any data on which to base a reasoned judgment. The only conclusion one can draw is that their reactions are purely intuitive, meaning they come from the subconscious mind. And why would the subconscious mind reject these techniques out of hand? Because structuring one’s analysis is fundamentally at odds with the way the human mind works.

Homo Sapiens—The Problem Solver

Human beings are problem solvers by nature. When our species arrived on the scene, every kind of human-eating predator could outrun us over a short distance—and a short distance was all a predator needed. Yet we managed to survive, not because of our physical attributes but because of our newborn intellect. Brain power had conveniently shifted the odds in Homo sapiens’ favor. But it wasn’t the size or weight of our brain that tilted the scales; it was the way we humans used our brains to solve problems, first and foremost being how to stay alive. Human problem-solving prowess not only ensured survival of our species but led ultimately to our dominion over the planet. Our present society, with its tiered self-government, legal institutions, medical practitioners, public services, educational institutions, modern conveniences, and sophisticated technology, bears unmistakable witness to our impressive capability to solve problems.

Most of us are quite comfortable with, if not proud of, our ability to analyze and solve problems, and we generally do moderately well at it—at least, we like to think we do. The fact is, however, that we mess up in our efforts to analyze problems much more often than we recognize or are willing to admit. Indeed, the road to humankind’s impressive achievements has invariably been paved with failures, many of which have set back our accomplishments by decades and longer. For every forward stride there have been telling missteps, because the problem-solving approach that has proven most practical and effective for the human species is the trial-and-error method. For every invention that finds its way to the marketplace, others end up in junkyards. For every new business that succeeds, others fail. For every business decision that earns big bucks, others lose money. In all human affairs, from marriage to marketing to management, success is generally built upon failure. And while some failures are justly attributable to bad luck, most result from faulty decisions based on mistaken analysis.

The Fallibility of Human Reasoning

The unwelcome fact is that, when it comes to problem solving, our mind is not necessarily our best friend. The problem lies in the way the mind is designed to operate.

I believe that psychologist Morton Hunt said it best in The Universe Within, his book about “the dazzling mystery of the human mind,” when he described our approach to problem solving as “mental messing around.” Naturally, if we structure our analysis, the mind can’t be totally free to mess around. That’s why the subconscious rebels when it’s asked to structure its thinking. Housemaids don’t do windows; the untrained human mind doesn’t do structuring.

Even so, structuring one’s analysis is intuitively a sound idea, so why do people reject it out of hand? Are they being irrational or paranoid? Neither. According to Professor Thomas Gilovich in his wonderful book, How We Know What Isn’t So, they are simply victims of “flawed rationality” caused by certain instinctive, unconscious tendencies of the human mind.

Over the past several decades cognitive science has discovered that we humans are unknowingly victimized by instinctive mental traits that defeat creative, objective, comprehensive, and accurate analysis. These traits operate below our consciousness, that is, in our unconscious mind.

All of us labor under the misperception that our conscious mind, the “I,” is somehow separate from the unconscious, and that the relationship between the two is that of a commanding officer to a subordinate. Research data simply do not support that model. Consider the following passage from Richard Restak’s The Brain Has a Mind of Its Own:

At the moment of decision we all feel we are acting freely, selecting at will from an infinity of choices. Yet recent research suggests this sense of freedom may be merely an illusory by-product of the way the human brain operates.

Consider something as simple as your decision to read this essay. You quickly scan the title and a few phrases here and there until, at a certain moment, you make the mental decision to read on. You then focus on the first paragraph and begin to read.

The internal sequence was always thought to be: 1. you make a conscious decision to read; 2. that decision triggers your brain into action; 3. your brain then signals the hands to stop turning pages, focuses the eyes on the paragraph, and so on.

But new findings indicate that a very different process actually takes place. An inexplicable but plainly measurable burst of activity occurs in your brain prior to your conscious desire to act. An outside observer monitoring electrical fluctuations in your brain can anticipate your action about a third of a second before you are aware that you have decided to act.

There is no question that the unconscious has a governing role in much of what we consciously think and do. A striking example was related in David Kahn’s The Codebreakers. Regarding the breaking of codes during World War II, he said that it required enormous volumes of text and corresponding quantities of statistics, and that the solutions took a heavy toll of nervous energy. One German cryptanalyst recalled, “You must concentrate almost in a nervous trance when working on a code. It is not often done by conscious effort. The solution often seems to crop up from the subconscious.”

As a result, we unwittingly, repeatedly, habitually commit a variety of analytic sins. For example:

We commonly begin our analysis of a problem by formulating our conclusions; we thus start at what should be the end of the analytic process. (That is precisely what happened at the meeting of Family Frozen Foods managers. Darfield began the discussion with the decision—a conclusion—that the solution to the backlog in deliveries was to expand the fleet of delivery trucks.)

We commonly begin our analysis of a problem by formulating our conclusions; we thus start at what should be the end of the analytic process. (That is precisely what happened at the meeting of Family Frozen Foods managers. Darfield began the discussion with the decision—a conclusion—that the solution to the backlog in deliveries was to expand the fleet of delivery trucks.)

Our analysis usually focuses on the solution we intuitively favor; we therefore give inadequate attention to alternative solutions. (Alternative solutions to Family Frozen Foods’ problem were never discussed. Moreover, the debate over which kind of truck to purchase was, at the very outset, restricted to two choices. Again, alternatives were never discussed.)

Our analysis usually focuses on the solution we intuitively favor; we therefore give inadequate attention to alternative solutions. (Alternative solutions to Family Frozen Foods’ problem were never discussed. Moreover, the debate over which kind of truck to purchase was, at the very outset, restricted to two choices. Again, alternatives were never discussed.)

Not surprisingly, the solution we intuitively favor is, more often than not, the first one that seems satisfactory. Economists call this phenomenon “satisficing” (a merging of “satisfy” and “suffice”). Herbert Simon coined the neologism in 1955, referring to the observation that managers most of the time settle for a satisfactory solution that suffices for the time being rather than pursue a better solution that a “rational model” would likely yield.

Not surprisingly, the solution we intuitively favor is, more often than not, the first one that seems satisfactory. Economists call this phenomenon “satisficing” (a merging of “satisfy” and “suffice”). Herbert Simon coined the neologism in 1955, referring to the observation that managers most of the time settle for a satisfactory solution that suffices for the time being rather than pursue a better solution that a “rational model” would likely yield.

We tend to confuse “discussing/thinking hard” about a problem with “analyzing” it, when in fact the two activities are not at all the same. Discussing and thinking hard can be like pedaling an exercise bike: they expend lots of energy and sweat but go nowhere.

We tend to confuse “discussing/thinking hard” about a problem with “analyzing” it, when in fact the two activities are not at all the same. Discussing and thinking hard can be like pedaling an exercise bike: they expend lots of energy and sweat but go nowhere.

Like the traveler who is so distracted by the surroundings that he loses his way, we focus on the substance (evidence, arguments, and conclusions) and not on the process of our analysis. We aren’t interested in the process and don’t really understand it.

Like the traveler who is so distracted by the surroundings that he loses his way, we focus on the substance (evidence, arguments, and conclusions) and not on the process of our analysis. We aren’t interested in the process and don’t really understand it.

Most people are functionally illiterate when it comes to structuring their analysis. When asked how they structured their analysis of a particular problem, most haven’t the vaguest notion what the questioner is talking about. The word “structuring” is simply not a part of their analytic vocabulary.

Most people are functionally illiterate when it comes to structuring their analysis. When asked how they structured their analysis of a particular problem, most haven’t the vaguest notion what the questioner is talking about. The word “structuring” is simply not a part of their analytic vocabulary.

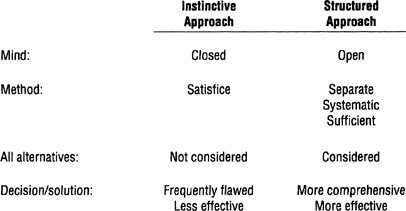

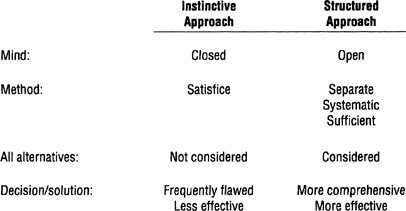

The difference between these two analytic approaches—intuitive and structured— can perhaps be better understood in Figure 1-1.

In the instinctive approach the mind generally remains closed to alternatives, favoring instead the first satisfactory decision or solution. Consequently, the outcome is frequently flawed or at least less effective than would be the case with the structured approach.

In the structured approach the mind remains open, enabling one to examine each element of the decision or problem separately, systematically, and sufficiently, ensuring that all alternatives are considered. The outcome is almost always more comprehensive and more effective than with the instinctive approach.

What are these troublesome instinctive mental traits that produce all these analytic missteps?

FIGURE 1-1

Problematic Proclivities

There are too many of these traits to treat all of them here, so I’ll focus on the seven (covered in detail in the Hunt and Gilovich books and in other cognitive scientific literature) that I believe have the greatest adverse effects on our ability to analyze and solve problems:

1. There is an emotional dimension to almost every thought we have and every decision we make.

Perhaps the mental trait with the greatest influence over our thinking is emotion. We are inarguably emotional creatures. Sometimes, as Daniel Goleman says in his thought-provoking book, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ, emotion is so strong that it hijacks—overwhelms—our power to reason. This is not news, of course. Alexander Pope wrote three hundred years ago that “What reason weaves, by passion is undone.” Still, the role that emotions, even subtle ones, play in our decision making is greatly underrated, if not dismissed, but it shouldn’t be. As Nancy Gibbs, writing in Time magazine in 1995 about Goleman’s book, said, “Whether we experience a somatic response—a gut feeling of dread or a giddy sense of elation —emotions are helping to limit the field in any choice we have to make.”

The message is obvious. We should check the state of our emotions when making important decisions. If our emotions are at high-energy levels, then we would be wise to postpone decision making until we can think more rationally. It is, of course, when emotions are running hot and a decision cannot be delayed that serious mistakes in judgment most often occur. At such times, even simple structuring of one’s analysis can be very rewarding.

2. Mental shortcuts our unconscious minds continuously take influence our conscious thinking.

We humans tend to believe that, by consciously focusing our mind on a problem, we are controlling our mental faculties and are fully aware of what’s going on in our gray matter. Unfortunately, that simply isn’t true. Most of what goes on in the mind involves “mental shortcuts” that occur without our knowledge and beyond our conscious control. These subroutines—which are comparable to computer “subroutines”—whir away constantly every second we are awake and, for all anyone knows, while we’re asleep. We normally aren’t aware they exist until we think about the lengthy, elaborate sequence of mental steps involved in an unconscious act such as catching a lightbulb someone playfully tosses at us. “Here, catch!” the tosser says, and without thinking we spontaneously dive to catch the bulb. Psychologists refer to this as a reflex action. It is also a mental shortcut—a subroutine.

Imagine the lengthy, intricate sequence of perception, association, recognition, coordination, and reaction the mind must go through to activate the muscles that move the arm, hand, and fingers to a position that will precisely intersect the lightbulb at a predicted point in its downward trajectory to catch the bulb and close the fingers gently around it. In a fraction of a second, the mind issues all of these complex motor commands and, what is more important, in the correct sequence, without our precognition or conscious participation. The mind accomplishes this remarkable feat by recalling from memory the commands, made familiar by lifelong practice, for catching an object with our favored hand. Obviously, the brain does not make a decision on each individual step of the entire sequence before sending the commands to the muscles. If it did, the bulb would smash on the floor long before the sequence was completed. Instead, the mind retrieves from memory the entire ready-made sequence and executes it.

The identical mental process occurs when we analyze a problem. The intricately interwoven neural networks of our brain react in concert to everything the brain senses: every sight, every sound, every bit of information. As Lawrence Shainberg wrote in Memories of Amnesia, “The name rang a bell. And once the bell was rung, others rang as well. That’s the miracle of the brain. No bell rings alone.” Each perception triggers hidden reactions whose silent tolling secretly influences our thoughts. For example, we hear someone say he or she is on a diet. We instantly stereotype that person according to our views concerning dieting. This stereotyping is an unconscious reaction of the mind. We do not consciously decide to stereotype; the mind does it for us automatically without our asking. It is a connection—a mental shortcut—that the mind instantly makes through its neural networks and that influences our perception of that person.

Mental shortcuts express themselves in a variety of forms with which we are all familiar: personal bias, prejudice, jumping to a conclusion, a hunch, an intuition. Two examples:

Your spouse—or a great and good friend who will accompany you—asks where the two of you should go on your next vacation. You think about it for a moment (the subroutines are whirring) and decide you’d like to go hiking in Vermont. Your spouse or friend suggests two alternatives, but they don’t appeal to you (whir, whir) as much as your idea does. And the more you think about your idea (whir, whir), the more appeal it has and the more reasons (whir, whir) you can think of why it’s a good idea. And in two minutes you’re in a heated argument.

Because these shortcuts are unconscious, we aren’t aware of them, nor do we have any conscious control over them. We are totally at their mercy, for good or bad. Usually for the good. For example, if I say “gun control,” you don’t have to struggle to understand the larger meaning of this phrase. Your mind is instantly, magically, awash with images, thoughts, and feelings about this controversial issue. You don’t decide to think and feel these things. Your unconscious mind takes mental shortcuts, flitting all over your brain, making thousands, perhaps millions, of insensible connections, recovering and reassembling memories and emotions, and delivering them to your conscious mind.

These shortcuts are part and parcel of what we call “intuition,” which is really a euphemism for the unconscious mind. That we humans are prone to place great store in intuition is understandable inasmuch as intuition was the mechanism that guided our evolution into the planet’s dominant—and smartest—species. Without our constant intuitive insights we humans probably would have become extinct eons ago. Albert Einstein said, “The really valuable thing is intuition.” I found this quote in The Intuitive Edge: Understanding and Developing Intuition by Philip Goldberg. Goldberg explains that intuition can be understood as the mind turning in on itself and apprehending the result of processes that have taken place outside awareness. But he notes that intuition cannot be ordered, commanded, implored, or contrived. We simply have to be ready for it.

What if I ask, “Who was the twenty-second president of the United States?” Your eyes close as you press a finger to your lips. “Let me think a minute,” you say. Think a minute? You’re not thinking, you’re waiting! Like you do when put on hold by a telephone operator, except in this case you’re waiting for your unconscious to come on the line, that is, to make its shortcuts deep down in your memory where Grover Cleveland’s name, face, and what-all are stored, probably, as cognitive and neural scientists speculate, in bits and pieces throughout your brain. If your unconscious fails to make those connections, you won’t remember who the twenty-second president was. It’s as simple and as complicated as that.

Mental shortcuts are what make people experts in their professions. Give a set of medical symptoms to an intern fresh out of medical school and ask him to diagnose the problem and recommend a treatment. Then give the same symptoms to a doctor with twenty years experience in that field. It takes the intern fifteen minutes to come up with a diagnosis and treatment; it takes the experienced doctor fifteen seconds. The doctor’s mind makes mental shortcuts based on accumulated knowledge from long experience. The intern’s mind can’t make these shortcuts yet, but it will in time.

We cannot “teach” the mind how to work; it works as it works, and taking shortcuts is one of its ways. These shortcuts are beyond our conscious control. We cannot stop the mind from taking shortcuts any more than we can will our stomachs to stop digesting the food we eat. And where those shortcuts lead our thinking is anyone’s guess.

3. We are driven to view the world around us in terms of patterns.

The human mind instinctively views the world in terms of patterns, which it recognizes based on memories of past experiences. We see a face (a pattern). Our mind searches its memory (the bells are ringing), finds a matching face (pattern), and delivers to our consciousness the name and other information stored with that pattern. This is not a conscious process. We don’t decide to remember the name associated with the face. The name just pops into our head. The unconscious mind, unbidden, does it for us.

We see patterns in situations. Let’s say the lights go out. We are not flustered or frightened. We light a candle or turn on a flashlight and wait for the electric company to restore power. How do we know power will be restored? Because such outages have occurred before; we know the pattern. Or let’s say we are watching a football game and see a referee give a hand signal. We know what the signal means; we’ve seen it before.

We see patterns in sequences of events. We know when to put mail into the mailbox because the postman arrives at the same time each day. We encounter a traffic jam, watch a police car and ambulance pass ahead of us with sirens wailing, and deduce that a traffic accident is blocking the road. It’s a familiar pattern. When we arrive home from work, our spouse does not greet us with a kiss and a smile; something has happened to upset the pattern. Because our brain is so thoroughly optimized as a pattern-recognition mechanism, we need only a fragment of a pattern to retrieve the whole from memory. And that retrieval is unconscious.

While this impressive capability is beneficial to our ability to function effectively, our compulsion to see patterns can easily mislead us when we analyze problems.

In the first place, patterns can be captivating. Consider, for example, the following numerical sequence: 40-50-60-__. Can you feel your mind pushing you to see 70 as the next number? If the mind were totally objective, it would evince no preference concerning the next number. But the mind is not objective; it perceives a pattern, is captured by it, and, having been captured, is disinclined to consider alternatives. Even though we may force the mind to consider other numbers, 70 will remain its preferred choice.

Unfortunately, the mind also can easily misconstrue random events as nonrandom, perceiving a pattern where, in fact, none exists. What do you see in Figure 1-2? An irregular hexagon? A circle? Actually, it is nothing more than six disconnected, randomly placed dots, but that’s not what our unconscious mind sees. It sees the dots as pattern-related elements of a whole. It instinctively, compulsively fills in the spaces between them and imprints the resulting image in our conscious mind. It can’t help itself. It’s the way it works.

A striking example of mistaken patterning was the initial reaction to the attack on Nancy Kerrigan prior to the U.S. National Figure Skating Championships in January 1994. Several newspaper columnists rashly cited the incident as further evidence of the rising risk to professional athletes of wanton violence by deranged fans. In short order, however, it became clear that the attacker was neither deranged nor a fan but a hit man hired by the ex-husband of Kerrigan’s chief competitor. The columnists had jumped to the wrong conclusion; they had mistaken the pattern.

But, what is worse, when we want to see a particular pattern or expect to see it, or have become accustomed to seeing it, not only do we fill in missing information but our mind edits out features that don’t fit the desired or familiar pattern.

FIGURE 1-2

We hear that a trusted colleague with whom we have worked for years is accused of sexually molesting children. We can’t believe it. We won’t believe it. It must be a mistake.

Historian Walter Lord, in Day of Infamy, a historical account of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, cites a perfect example:

People all over Oahu couldn’t believe that what they were seeing was an enemy attack: unidentified planes, falling bombs, rising smoke. It was just the Army fooling around, it was just this, it was just that. Anything but the unbelievable truth.

The ease with which the human mind can misidentify a pattern is one of the things that makes us laugh at jokes. Take this story:

A man, walking down the street, passes a house and notices a child trying to reach a doorbell. No matter how much the little guy stretches, he can’t reach it. The man calls out, “Let me get that for you,” and he bounds onto the porch and rings the bell. “Thanks, mister,” says the kid. “Now let’s run.”

What makes the anecdote funny is that our mind has quickly conjured an image—a pattern—of a nice man helping a sweet little child, when suddenly we discover we are fooled. It’s a prank. We misidentified the pattern.

Stereotyping is a form of patterning: perceiving a similarity between two events or things because of superficial features and then, based on that perceived similarity, unconsciously ascribing to one of the events additional attributes of the other. We live by stereotyping; it underlies a great deal of our everyday behavior; it is a principal mechanism of the mind.

Stereotyping, of course, governs racial, ethnic, and every other type of bigotry. Let’s say that I don’t like a particular law firm in my city. I meet someone and ask where he or she works. The person says he or she works for that firm. Instantly, in a thousandth of a second, before I can reason my thinking, my prejudice against the law firm dominates my reasoning and I get a negative impression of this person. The insidious part is that I have to struggle against this impression to see this person as he or she really is; I have to struggle against my own mind. As I said, the mind is not always our best friend.

ABC-TV’s Prime Time Live conducted a fascinating experiment that demonstrated the hidden power of stereotyping. The results, presented on the program on June 9, 1994, revealed blatant age discrimination in hiring by a number of different companies. In the experiment the interviewee (an actor) played the role of two men: one in his twenties, the other disguised to appear in his fifties. In a number of interviews, despite the fact that the older man had more relevant job experience, the younger man received the job offers; the older man received none. Even when two of the job interviewers were told of the double role playing, they insisted their decision to hire the younger man had not been influenced by age bias. However, the hidden video-audio tapes of the interviews showed, without any question, that the interviewers were instantly put off by the older man’s age.

The ABC segment demonstrated two powerful features of the mind’s instinct to pattern: the patterning is instantaneous, and the mind’s owner is unconscious of it. The two interviewers’ denial that they had been biased shows that people don’t want to admit there are things going on in our minds that we aren’t aware of and that we have no control over. We like to think we are in control of our minds, but the ABC experiment clearly showed we are not.

Another kind of patterning is the tendency of the human mind to look for cause-and-effect relationships. Regarding this tendency, Morton Hunt said in The Universe Within that attributing causality to an event which is regularly followed by another is so much a part of our everyday thinking that we take it for granted and see nothing extraordinary about it. We seem to view the world in terms of cause and effect, and we somehow instinctively know the difference between the two concepts. This has been demonstrated unequivocally in experiments, even with infants. So we by nature strive to know why something has happened, is happening, or will happen and what the result was, is, or will be. Anthropologist Stephen Jay Gould said of patterning: “Humans are pattern-seeking animals. We must find cause and meaning in all events… everything must fit, must have a purpose and, in the strongest version, must be for the best.”

This compulsion, while obviously helpful in dealing with the world around us, can deceive us when we analyze problems, because we often perceive cause and effect when no such relationship exists.

A man awoke one morning to find a puddle of water in the middle of his king-size water bed. To fix the puncture, he rolled the mattress outdoors and filled it with more water so he could locate the leak more easily. But the enormous mattress, bloated with water and impossible to control on his steeply inclined lawn, rolled downhill, smashing into a clump of thorny bushes that poked holes in the mattress’s rubbery fabric. Disgusted, he disposed of the mattress and its frame and moved a standard bed into his room. The next morning he awoke to find a puddle of water in the middle of the new bed. The upstairs bathroom had a leaky drain. Mistaken cause and effect. It happens all the time.

It is the false perception of a cause-and-effect relationship that enables magicians to trick us—or more correctly, to trick our minds—so easily with illusions. I am ever intrigued by the reaction of audiences to magicians’ performances. The spectators are amused and surprised, apparently little realizing that the illusions they see on the stage are no different than those that occur daily in their lives but pass undetected. Each of us would be amazed at the number of times each day we perceive patterns of all types that are not what they appear to be. It is false perceptions, of course, that enable con artists to fleece people out of huge sums of money on pretexts that, in the clear light of retrospect, are flatly implausible and make the victims wonder how they were so easily fooled.

Another example. Retail sales drop during a period of heavy snowstorms. A sales manager has observed this pattern before and figures sales will rebound when the weather clears. Perhaps they will, but he should consider alternative interpretations in case he has misread the cause-and-effect relationship. But will he consider alternatives? Probably not. His unconscious mind is captivated by the presumed connection (the cause-and-effect pattern) between the weather and the loss of sales.

4. We instinctively rely on, and are susceptible to, biases and assumptions.

Bias—an unconscious belief that conditions, governs, and compels our behavior—is not a new concept. Eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant theorized that the mind is not designed to give us uninterpreted knowledge of the world but must always approach it from a special point of view … with a certain bias.

Almost everything we do is driven by biases. For instance, when we walk into a dark room (and recognize the dark room “pattern”), we instinctively reach for the light switch on the wall. What prompts this action is the unconscious belief (the bias) that flipping the switch will bring light to the room. We know this because we have experienced the “flip-the-switch-make-the-light-go-on” cause-and-effect pattern before. The depth of our bias becomes apparent whenever we flip the switch and the light doesn’t come on. We’re surprised; our belief has been invalidated; suddenly we are conscious of the bias. We get the same reaction when we turn the spigot on a faucet and no water comes out—something we have always assumed was true (a cause-and-effect pattern) turns out to be false. I will keep reaching for the wall switch until I determine through experience that doing so won’t produce light. Then I’ll have a new bias: the bulb has burned out, and switching it on won’t bring light. I’ll then operate on the basis of the new bias until the bulb is replaced, at which point I’ll revert to the original bias.

The shortcut mechanism of bias is, like the other mental traits, instinctive and outside our control. Acquiring a bias is not a conscious mental process; we really don’t have a role in it. The mind does it for us without our knowledge or conscious input. So we are stuck with biases whether we want them or not, and they influence everything we think about and do. It’s the way the mind works.

Although customarily viewed as a pejorative term, bias is generally a good thing. As with our other human mental traits, we would be dysfunctional without it. It is bias that enables us to repeat an action we have taken before without going through all of the mental steps that led to the original act. In this sense, bias is a preconditioned response. Thus, I am inclined (biased) to hold a golf club in a certain way because I have held it that way before. I shave my face every day as I have shaved it before. I brew coffee today as I did yesterday.

For the most part our biases, and the assumptions they both breed and feed upon,* are highly accurate and become more so as we grow older. This phenomenon is evidenced, for example, by the fact that older drivers have fewer accidents than younger drivers, despite the younger set’s quicker, sharper reflexes. Older drivers have experienced more dangerous situations (patterns), have seen what happens when certain actions are taken in those (cause-and-effect) situations, and have developed self-protective biases that avoid accidents. In short, much more often than not, our biases lead us to correct conclusions and reactions, and they do it exceedingly fast. They are what make us humans smart. Without them, we would be unintelligent.

While biases enable us to process new information extremely rapidly by taking mental shortcuts, the rapidity of this process and the fact that it is unconscious—and thus uncontrollable —have the unfortunate effect of strengthening and validating our biases at the expense of truth. The reason, explained in Section 6 below, is that we tend to give high value to new information that is consistent with our biases, thus reinforcing them, while giving low value to, and even rejecting, new information that is inconsistent with our biases thus preserving them. New information that is ambiguous either is construed as consistent with our biases or is dismissed as irrelevant. In this respect, biases are, like deadly viruses, unseen killers of objective truth.

Hidden biases are the prime movers of the analytic process. They spring to life spontaneously whenever we confront a problem. They are imbedded like computer chips in our brain, ready to carry out their stealthy work at the drop of a problem. By “stealthy” I don’t mean to indicate that all of our hidden biases are detrimental or sinister; as I said, they enable us to function effectively in the world. But biases, like those other instinctive human mental traits, can lead us astray. Because it is uncharacteristic of Homo sapiens to identify, much less evaluate or—heaven forbid, challenge—the hidden biases underlying one’s perspective of a problem, we are unwitting slaves to them. What is more, because most biases are hidden from our consciousness, we aren’t aware of their existence or of their effects, good or bad, on our analysis, conclusions, and recommendations.

The common perception of the intrepid male sperm tellingly illustrates the powerful and lasting adverse effects of bias. For decades biologists have portrayed sperm as stalwart warriors battling their way to a quiescent, passive egg that can do little but await the sturdy victor’s final, bold plunge. But, as David Freedman explained in the magazine Discover in June 1992, this is a grand myth. In fact, sperm struggle to escape from the egg but are “tethered” in place until the egg can absorb one of them. Yet popular literature, textbooks, and even medical journals are crammed with descriptions of warrior sperm and damsel-in-distress eggs.

The strong bias biologists acquired early in their careers in favor of a macho sperm skewed their observations.

A research team at Johns Hopkins, even after having revealed the sperm to be an escape artist and the egg to be a chemically active sperm catcher, continued for three years to describe the sperm’s role as actively “penetrating” the egg.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin described the way sea urchin sperm first make contact with an egg by quickly stringing together protein molecules into a filament that extends out until it reaches the egg. But instead of describing this as an innocuous process of assembly and attachment, the group wrote that the sperm’s filament “shoots out and harpoons” the egg.

When a researcher at the Roche Institute of Molecular Biology wrote of his discovery that mouse eggs carry a molecular structure on their coating that fits inside a complementary structure on the sperm, helping bind the two together, he described the two structures, naturally enough, as a lock and key, but he called the egg’s protruding structure the lock and the sperm’s engulfing structure the key.

It is only when the truth jolts our complacency, making us realize there is something wrong with our reasoning, that we are moved to identify and rethink our biases. Maybe all white southerners aren’t racists. Maybe all Italians aren’t members of the Mafia. Maybe violence on TV does have a harmful effect on our society.

The trouble with biases is that they impose artificial constraints and boundaries on what we think. The insidious part is that we aren’t even aware that our thinking is restricted. We go about our daily problem solving believing we are exercising freedom of thought, when in fact our thinking is as tightly bound by our biases as an Egyptian mummy is by its wrappings.

A store manager discovers that money is missing from a cash box, but she dismisses the idea that Glenn, the cashier, stole the money. If he was responsible for the cash being missing, he made an honest mistake. Her instantaneous conclusion (it pops into her head before she can say Abraham Lincoln) is “Of course he didn’t steal the money. He’s as honest as the day is long.” Then those other troublesome mental traits take over and finish what the unconscious shortcut began. Having rationalized away the possibility that he was a thief, she defends her instant conclusion from challenges from those who aren’t acquainted with the cashier and who, like their Missouri relatives, need to be shown that the cashier is as Lincolnesque as she purports. She casts aside their doubts and dismisses their arguments, placing greater stock in her own assessment of his integrity. That assessment is based, of course, on the assumption (the bias) that the cashier is an honest person. If it turns out he is dishonest, her whole line of reasoning collapses like a windblown house of cards.

Another troublesome phenomenon, this one linked with Alexander Pope’s enduring maxim “A little learning is a dangerous thing,” is that the more we know about a subject, the more our biases affect our understanding of it, for better or worse. As you can well imagine, this phenomenon can play havoc with analysis of problems. That exact phenomenon is occurring at this very moment with regard to your knowledge of what it means to structure analysis. The more you learn about the subject, the clearer your perceptions about it become. But I use the word “clearer” advisedly, because your biases are hard at work and there’s no telling how they may be distorting your understanding of what you’re reading here.

Rank the risk of dying in the following seven circumstances —rank the most risky first, the least risky last:

Risk of Dying

For women giving birth

For anyone thirty-five to forty-four years old

From asbestos in schools

For anyone for any reason

From lightning

For police on the job

From airplane crashes

The following table gives the actual rank order and odds of dying.

| Risk of Dying |

|

| For anyone for any reason |

1 in 118 |

| For anyone 35 to 44 years old |

1 in 437 |

| For police on the job |

1 in 4,500 |

| For women giving birth |

1 in 9,100 |

| From airplane crashes |

1 in 167,000 |

| From lightning |

1 in 2 million |

| From asbestos in schools |

1 in 11 million |

| Source: Robert J. Samuelson, “The Triumph of the Psycho-Fact,” The Washington Post, May 4,1994, p. A25. |

How accurate was your ranking? Did you greatly overrate the risk of one of the circumstances? If so, a likely reason is another factor related to bias that inhibits our ability to analyze problems objectively. It is called the vividness effect. Information is vivid because it was acquired either traumatically or recently and thus has made a strong impression on our memory. Information that is vivid is therefore more easily remembered than pallid, abstract information and, for that reason, has greater influence on our thinking. This influence can far exceed what the information really deserves.

A house burns down, and authorities suspect a child’s playing with matches was the cause. If you set fire to your house as a child while playing with matches, the image of a child lighting matches would be vivid and personal. You would therefore be prone to put more credence in the authorities’ suspicion than someone who had not had your experience, and your objectivity would be reduced accordingly.

The vividness effect is not something we elect to have. It’s an inherent feature of the human mind—a package deal. It comes with the way our minds are programmed. It’s the way the mind works.

The Analog Mind

The reason biases can so easily lead us astray is that the mind doesn’t rigorously test the logic of every new piece of information it receives. If it did, our mental processes would grind to a halt, and the mind—and we—would be dysfunctional. Instead, the mind takes a shortcut by patterning: treating the new information as it did the old, drawing the same conclusions, experiencing the same feelings, taking the same actions. Thus, the mind operates analogically, not logically.

In The Universe Within, in a section entitled “A Flunking Grade in Logic for the World’s Only Logical Animal,” Morton Hunt writes:

Most human beings earn a failing grade in elementary logic…. We’re not just frequently incompetent [in thinking logically], we’re also willfully and skillfully illogical. When a piece of deductive reasoning leads to a conclusion we don’t like, we often rebut it with irrelevancies and sophistries of which, instead of being ashamed, we act proud.

(This brings to mind the emphatic denial by the two interviewers in ABC’s experiment that they had been guilty of age discrimination.)

Jeremy Campbell, an Oxford-educated Washington correspondent of the London Standard newspaper, in his book about the human mind, The Improbable Machine, agrees with Hunt’s observation:

Compelling research in cognitive psychology has shown that we are logical only in a superficial sense; at a deeper level we are systematically illogical and biased…. Highly intelligent people, asked to solve a simple problem calling for the use of elementary logic, are likely to behave like dunderheads…. If we want to get to know the mind, logic is the wrong place to start. There is no innate device in the head for doing logic.

A prime illustration of how innately illogical most of us are is how people rush to buy tickets in a multimillion-dollar lottery in the days preceding the drawing, knowing their chances of winning are less than their chance of being struck twice by lightning in bed on the same night. They justify their illogical behavior with a variety of silly statements such as “Someone is going to win, and it might as well be me” and that all-time winner “I have as good a chance as anyone.”

As Hunt says, “Despite the uncertainties [of our analogical approach to problem solving], it seems over the millennia to have been fixed in us … by success; the errors we make are small in comparison to our gain in coping with the world.” People who place great stock in logical thinking may look down upon human analogical reasoning, but, as Hunt observes, we humans could not survive without it.

Recall my example of entering a darkened room. I didn’t have to go step by step through a logical sequence of thoughts to decide to reach out and flip the light switch. My mind, comparing this situation with others I had encountered and finding a matching pattern, retrieved from memory what action I had taken previously. My mind thus leapfrogged (took a shortcut) over an otherwise complex logical sequence and directed me to flip the switch. This is the principal way in which we interpret and deal with the physical world around us: we interpret new experiences in light of old ones and make inferences based on similarities.

One of the inferences we routinely and unconsciously make is detecting when something is “illogical.” What if someone asks, “How high can a giraffe fly?” Instantly our mind tells us the question is “illogical.” We don’t have to think about it; we instantly know. Yet how do we know? An educated guess is that the mind compares the new information about the giraffe with the old information the mind has stored away about the animal. Not only does the new information not match the old, it clashes violently, and the mind tells us it doesn’t match, meaning it doesn’t make sense. This is a far cry from reasoning or rational thinking, and it’s certainly light-years away from formal logic. Formal logic would address the question in something like the following syllogism:

It stands to reason that, given early humans’ acquisition of a giant brain of immense intellectual potential, some members of the species may have experimented with logical thinking. I can visualize Rodin’s statue of The Thinker as an early human sitting naked on a boulder outside his cave, head down, chin in hand, formulating syllogisms to explain the nature of existence. (Don’t laugh!) If logical thinking was ever seriously toyed with by early humans, it was quickly extinguished as an evolving human trait, for not only did it offer no redeeming advantage, it was downright dangerous.

Imagine two early humans—A and B—walking together across the ancient savanna. It is the close of the day, and the sun is low on the horizon. A gentle breeze is cooling the hot, dry air. Suddenly, the pair catch sight of a shadow moving nearby in the tall grass. Early Human A stops to ponder logically what the shadow might be. A gazelle? A water buffalo? A chimpanzee? Perhaps a wild boar? Perhaps a lion? Meanwhile, Early Human B has run off to find safe refuge in a tall tree or a cave. Those early humans represented by A, who analyzed the situation logically to determine what steps to take, were, as modern-day Darwinian personnel managers would say, “selected out,” while early humans of the B type, who instead applied what cognitive scientists call “plausible reasoning,” survived to plausibly reason another day. Over time it was the B types that populated the earth.

What is plausible reasoning? “Plausible” means “seemingly true at first glance.” Plausible reasoning (also referred to as “natural” reasoning) is our practice of leaping to a conclusion that is probably correct based on the recognition of similarities between the situation confronting us at the moment and one that confronted us in the past. This is analogical thinking—patterning. We infer from the similarities that the two situations are probably alike. In the case of Early Human B spotting a shadow in the grass and recalling an earlier occasion when the shadow was a lion, B could plausibly conclude that it would be in his or her best interest in the present situation to get the hell out of there.

As Morton Hunt put it, “Natural [plausible] reasoning often succeeds even when it violates laws of logic. What laws then does natural reasoning obey?” He cited two: plausibility and probability. “In contrast to logical reasoning,” said Hunt, “natural reasoning proceeds by steps that are credible [plausible] but not rigorous and arrives at conclusions that are likely [probable] but not certain.”

Because logic, to be effective, requires total consistency and total certainty, logical thinking is unsuited for dealing with the real world in which the only certainty (other than taxes and TV commercials) is ultimate death. But plausible reasoning requires neither consistency nor certainty. If we had to be wholly consistent and certain, we could hardly think at all, for most of our thinking, as Hunt astutely observed, is as imperfect as it is functional.

Thus, when early Homo sapiens was confronted with potential threats, plausible reasoning traded an uncertain probability of risk for the certainty of survival. If there were only a 1 percent chance that the shadow moving in the grass was a carnivore, then, on average, one out of every umpteen times a human stuck around to find out what the shadow was, the human would get eaten. But if the human ran away whenever a shadow moved in the grass, that human survived 100 percent of the time. It doesn’t take a graduate degree in formal logic to figure out which course of action was more beneficial to survival. Plausible reasoning ensured survival; logical reasoning didn’t. Logical reasoners were penalized (weeded out over time); plausible reasoners were rewarded (proliferated over time). We therefore can confidently conclude, without need of extensive confirmatory studies through congressionally funded federal grants, that thinking logically (logical thinking), was not only not a prerequisite for our survival as a species but was, in fact, a liability.

Mind-set

The mother of all biases is the “mind-set.” Each of us, over time, as we acquire more and more knowledge about a subject, develops a comprehensive, overall perspective on it, as in President Ronald Reagan’s famous view of the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” We call such a perspective a mind-set, which refers to the distillation of our accumulated knowledge about a subject into a single, coherent framework or lens through which we view it. A mind-set is therefore the summation or consolidation of all of our biases about a particular subject.

A mind-set thus exerts a powerful influence, usually for the best, on how we interpret new information by spontaneously placing that information in a preformed, ready-made context. For example, when we learn that a close relative has died, we instantaneously experience various sentiments generated by our mind-set concerning that relative. We don’t first systematically recall and reexamine all of our interactions with that person, gauge our reactions to each one, and then decide to feel remorse about the person’s death. The feelings come upon us in a flash; we don’t think about them before we sense them. Such is the power of mind-set.

Upon learning from a radio sports program that our favorite team has won a particular game, our mind-set on that team makes us pleased. But we are ambivalent about the results of other games because we have not developed mind-sets on the teams involved. When we read a novel, the personality of a particular character evolves from page to page as the author furnishes us bits of information about the character’s life, desires, fears, and such. At some point, our absorption and interpretation of these small details solidify into a particular mind-set. If the author is skilled, this mind-set is precisely the one he or she intended us to acquire. We perceive the character as good or evil, happy or sad, ambitious or content and interpret the character’s thoughts, statements, and actions within the framework of this manufactured mind-set.

Mind-sets enable us to interpret events around us quickly and to function effectively in the world. We unconsciously acquire mind-sets about everything—friends, relatives, neighbors, countries, religions, TV programs, authors, political parties, businesses, law firms, government agencies, whatever. These mind-sets enable us to put events and information immediately into context without having to reconstruct from memory everything of relevance that previously happened. If I ask you, “What do you think of the collapse of health care reform?” you know instantly what I’m talking about. I don’t have to explain the question. Mind-sets therefore provide us instant insight into complex problems, enabling us to make timely, coherent, and accurate judgments about events. Without mind-sets, the complexity and ambiguity of these problems would be unmanageable, if not paralyzing.

Being an aggregate of countless biases and beliefs, a mind-set represents a giant shortcut of the mind, dwarfing all others the mind secretly takes to facilitate thinking and decision making. The influence a mindset has on our thinking is thus magnified by many orders of magnitude over that of a simple bias, such as the way I shave in the morning. For that reason, mind-sets are immensely powerful mechanisms and should be regarded both with awe for the wonderful ease with which they facilitate our functioning effectively as humans and with wariness for their extraordinary potential to distort our perception of reality.

Consider, for example, the observation of newspaper columnist William Raspberry concerning the pretrial hearing of O. J. Simpson for the murder of his former wife and her friend.

Sixty percent of black Americans believe O. J. Simpson is innocent of the murder charges against him; 68 percent of white Americans believe him guilty. How can two groups of people, watching the same televised proceedings, reading the same newspapers, hearing the same tentative evidence, reach such diametrically opposed conclusions?

Donna Britt, a Washington Post newspaper columnist, writing about racism’s influence on the public’s pretrial attitudes concerning Simpson’s culpability, said that some blacks believe that no black person can be guilty of wrongdoing, no matter what the accusation or evidence. She said these blacks have an ingrained cultural memory of their men being dragged away into the night, never to be seen again; they have grappled with racism, have found it staring at them, taunting them, affecting them so often that sometimes they see it even when it isn’t there: “It can obscure people’s vision so completely that they can’t see past it…. Some stuff goes so deep, we may never get past it.”

The case of the mysterious explosion on the battleship U.S.S. Iowa, which serves as the subject of one of the exercises in Chapter 11, presents another example of a mind-set. An article in U.S. News & World Report described how different people interpreted the personal belongings in the bedroom of Seaman Clayton Hartwig, whom the Navy suspected of intentionally causing the explosion: “Indeed, the lines of dispute are so markedly drawn that Hartwig’s bedroom seems emblematic of the whole case. Some see only a benign collection of military books and memorabilia. Others see criminal psychosis in the very same scene.”

Once a mind-set has taken root, it is extremely difficult to dislodge because it is beyond the reach of our conscious mind. And unless we carefully analyze our thinking, we probably won’t be aware that we have a particular mind-set. The question then is, if we aren’t aware of our biases and mind-sets, how can we protect ourselves against their pernicious negative effects? It seems to be a Catch-22.

There is only one way to change undesirable biases and mind-sets, and that is by exposing ourselves (our minds) to new information and letting the mind do the rest. Fortunately, the mind is, to a large degree, a self-changing system. (You will note I didn’t say “self-correcting.” The correctness of a bias or mind-set is determined entirely by the culture in which it exists.) Give the mind new information, and it will change the bias. We sample a food we’ve always avoided, only to discover it tastes good. We read a book by an author we have always detested, only to find we enjoy her writing. We are forced by circumstances to collaborate on a project with someone we have always disliked, and we end up liking that person.

Most biases and mind-sets, however, are highly resistant to alteration and are changed only gradually, eroded away by repeated exposure to new information. An example was white America’s awakening bit by bit through the 1950s and ’60s to the reality and evils of racial discrimination. Some biases and mind-sets are so deeply rooted that they can be corrected only by truth shock treatment. After the capitulation of the Nazi regime in World War II, many German citizens who for years had stubbornly denied reports of Nazi atrocities were forced to tour “death camps.” The horrors they saw there instantly and permanently expunged their disbelief. Similar shock treatment sometimes occurs in marriage counseling and drug addiction therapy when people are confronted with the stark reality of their aberrant or harmful behavior.

5. We feel the need to find explanations for everything, regardless of whether the explanations are accurate.

It isn’t that we humans like to have explanations for things; we must have explanations. We are an explaining species. Explanations, by making sense of an uncertain world, apparently render the circumstances of life more predictable and thus diminish our anxieties about what the future may hold. Although these explanations have not always been valid, they have enabled us through the millennia to cope with a dangerous world and to survive as a species.

The compulsion to explain everything drives our curiosity and thirst for knowledge of the world. As far as I know, Homo sapiens is the only species that seeks knowledge or evinces any awareness of the concept. Knowing—finding an explanation for an event—is one of the most satisfying of human experiences. There is great comfort in recognizing and making sense out of the world. Doing so creates order and coherence, and, where there is order, there is safety and contentment. We are instantly aware of the loss of this inner feeling of safety and contentment the moment we don’t recognize a pattern in a situation that confronts us.

Finding explanations goes along with our compulsion to see cause-and-effect relationships and other patterns. Once we identify a pattern, we generally have little trouble explaining or having someone else explain for us how it came to be and what it means. It’s an automatic, uncontrollable response that we experience constantly. We explain our actions to others and listen attentively while others explain their actions to us. We say to a friend, “Mary’s late for work today.” And the friend immediately explains, “Oh, she’s probably …” And we acknowledge the explanation: “Yeah, maybe you’re right.” News media explain current events while we assimilate the explanations like students in a classroom. Sports commentators “calling” a game explain the meaning of the plays and the teams’ competing strategies while we happily process their comments. A young man explains to his father how the family car became dented while the father eagerly but skeptically awaits a full explanation. We are an explaining species; we could justifiably have been labeled “Homo explainicus” As Gilovich says: “To live, it seems, is to explain, to justify, and to find coherence among diverse [things. It would seem the brain contains a special module]—an explanation module that can quickly and easily make sense of even the most bizarre patterns of information.”

Read the following paragraph; it’s a puzzle:

I walked to the bank. No one was there. It was Tuesday. A woman spoke to me in a foreign language. I dropped a camera and, when I stooped to pick it up, the music began. It had been a long war. But my children were safe.

Do you feel your mind struggling to make sense of these seemingly disconnected bits of information? Do you experience a subtle but nonetheless tangible frustration and discomfort as you grope to shape these bits into a recognizable pattern? But you can’t. The information is too jumbled, truncated, and disconnected. Still, something inside us tries to make sense of it, to sort it out—if you’ll pardon the expression—logically. We unconsciously grapple with the sentences looking for a connection, some common thread that will bind the information together as a whole.

If we can’t immediately perceive a connecting pattern, the mind manufactures one, either by filling in “missing” information, as happened with the six randomly placed dots, or by eliminating “unrelated” or “irrelevant” information. In something akin to desperation, we force-fit a pattern to relieve our discomfort. Edmund Bolles, in his fascinating book about human perception, A Second Way of Knowing, says, “We expect everything we perceive to mean something. When presented with an image that has no larger meaning, we find one anyway.”

Of course, the whole process of force-fitting a pattern occurs so quickly that we usually are not conscious of any discomfort. But make no mistake about it, the discomfort is there, in our mind. And if our mind is unable to come up with a satisfactory pattern after only a few seconds, the discomfort will become palpable.

This is the same discomfort we feel when we hear a dissonant chord in music. We don’t need to be told or taught that the chord is dissonant; we instinctively know it, just as we instinctively feel a combined sense of relief and pleasure when the chord resolves into a harmonious mode. That’s what the word harmony means in music: an agreeable, pleasing combination of two or more tones in a chord. Harmony (knowing) is pleasing; dissonance or disharmony (not knowing) is displeasing.

But, you don’t need to manufacture a pattern for the seemingly unrelated sentences in the puzzle paragraph above. I’m furnishing you the solution or, as Paul Harvey put it, “the rest of the story”:

The end of World War II had just been declared. I was in a little French town on my way to a bank. That Tuesday happened to be a French national holiday, so the bank was closed. A French woman, celebrating the armistice, handed me her camera and asked me to take a photograph of her and her husband. I accidentally dropped the camera, at which point the French Marseillaise began playing from a loudspeaker in the center of the town. I was touched with emotion. My two sons had fought with American forces. It had been a long war, but they were safe.

Don’t you now experience a certain mixed feeling of satisfaction, relief, and contentment in seeing how the sentences relate to one another?

Humans have to know things. Knowing is satisfying and comforting; not knowing is unsettling. Wanting to know, needing to know, is a fundamental human trait. We giggle at the reader who skips to the last pages of a mystery story to learn whodunit, but that reader, who unconsciously responded to a deep-seated instinct ingrained in our species over the millennia and whose curiosity has been sated, cares not what we think. On a grander, nobler scale, historians spend years doing in-depth research to understand —find explanations for—the course of human events. And here, in this book, I the author and you the reader are likewise looking for explanations. It is what we humans do. It is, like all those other traits, what makes us human.

Unfortunately, our compulsion to explain things can, like those other traits, get us in trouble. When presented with an event that has no particular meaning, we find one anyway, and we subconsciously don’t care whether the explanation is valid.

In March 1996, an animal house burned down at the Philadelphia zoo while two zoo guards were making personal phone calls in their office. When asked about the fire, they said they had smelled smoke near the building about two and a half hours earlier, but they thought it was coming from a nearby railyard. When confronted with a situation, they made up an explanation, were satisfied with it, and returned to their office. Twenty-three primates were killed. The two guards were fired.

In 1974, a Northwestern University professor was helping a young man try to get his manuscript published, but their efforts were rejected. The author became extremely angry. Five weeks later, an explosion rocked the campus. The professor wondered, just for a second, whether there could be a connection between the explosion and the young man’s anger, but dismissed the idea as farfetched. He was confronted with a situation, made up an explanation, was satisfied with it, and went about his business. Twenty years later he learned that the young man he had helped was Theodore J. Kaczynski, the so-called Unabomber, convicted of an eighteen-year spree of bombings that killed three people and injured twenty-three others.

Likewise, when analyzing problems, we sometimes come up with explanations that don’t represent the evidence very well, but we use them anyway and feel comfortable doing it. Again, we subconsciously don’t care whether the explanation is valid. Its validity is simply not a factor. It’s those pesky biases and mind-sets at work again.

Our indifference to the validity of our explanations is stunningly profound! It speaks volumes about the human mental process, for the astonishing, sobering, worrisome fact is that the explanations we give for things don’t have to be true to satisfy our compulsion to explain things.

Let’s pause a moment and reflect on this observation, which, in my humble opinion, presents an awesome insight into the workings of the human mind and into human behavior. Think about it. There’s an autonomous, unconscious mechanism in your mind and mine that switches to “satisfied” when we’ve finished formulating an explanation for something.

We are awakened late at night in our upstairs bedroom by a noise downstairs. We tell ourselves it’s the cat. And we roll over and go back to sleep.

And, being satisfied, we are then blithely content to move on to something else without seriously questioning our explanation. This is one of the reasons we humans don’t give sufficient consideration to alternatives. And not considering alternatives is, as I pointed out at the beginning of this book, the principal cause of faulty analysis.

6. Humans have a penchant to seek out and put stock in evidence that supports their beliefs and judgments while eschewing and devaluing evidence that does not.

Please do a quick experiment with me. Stop reading this page and direct your attention for a few seconds to the wall nearest you.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONCENTRATE ON THE NEAREST WALL.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONCENTRATE ON THE NEAREST WALL.

If you did as I requested, you immediately asked yourself, “What about the wall? What am I supposed to be looking for?” And you were right to ask that question, because I didn’t tell you what to focus on. You see, our eyes are almost always focused, always riveted on some object. But our eyes are merely an appendage, an extension of the mind. They do the mind’s bidding, and that constant bidding is to focus. When we don’t let the mind focus, it goes into a quasi state of shock, sort of a miniparalysis, which we sense through mild mixed feelings of disorientation, anxiety, and frustration. Imagine being told to look at that wall near you for thirty minutes without knowing what you’re supposed to be looking at. The very thought of it makes me shudder. In such a situation, the mind becomes discomforted and communicates that discomfort by making us nervous and impatient. We thus are prompted to think or even say aloud “What am I supposed to be looking at? What’s the point?” In other words, what’s the focus?

Focusing

We humans are focusers by nature. It is a trait deeply imbedded in our mental makeup, one we share with every other warm-blooded creature on this planet. (In fact, all living organisms are prone to focus “mentally,” but we’ll save that discussion for another day.) Consider, for example, the playful, skittish squirrel. While scampering about the ground, foraging for food, the squirrel suddenly freezes in an upright posture. Some movement or sound has caught its attention. The animal holds perfectly still, watching, waiting, ready to dash up a tree to safety at the first sign of danger. While the animal remains in this stock-still position, its “mind” and all of its senses are totally focused on the potential threat. All other interests of the squirrel are in abeyance. Focusing is, indeed, not a uniquely human trait.

In A Second Way of Knowing, Edmund Bolles says the following about “attention” (a synonym for “focus”):

We shift attention from sensation to sensation, watching only part of the visual field, listening to only some sounds around us, savoring certain flavors amid many. Our capacity to select and “impart intensity”* to sensations prevents us from being slaves to the physical world around us.

Reality is a jumble of sensations and details. Attention enables us to combine separate sensations into unified objects and lets us examine objects closely to be sure of their identity.