There is only one answer.

There is only one answer.Examples: Who is buried in Grant’s tomb?

Who is the governor of New York?

Before addressing the core topic of this book—analytic structuring techniques—allow me to offer five important insights into effective problem solving.

First, nearly all situations, even the more complex and dynamic, are driven by only a few major factors. Factors are things, circumstances, or conditions that cause something to happen. Factors, in turn, beget issues, which are points or questions to be disputed or decided.

Consider an accident involving two cars. The major factors (the circumstances that caused the accident) are such things as reckless driving, driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, failure to yield the right-of-way, excessive speed, mechanical failure, and so on. The major issues (the points to be disputed or decided) are derived from such factors as: Who was driving each car? How fast were they driving? Had they been drinking alcoholic beverages? Did they violate any laws? And so on. Factors beget issues; issues stem from factors.

Major factors and major issues are the navigational aids of analysis; they tell us where our analysis should be headed. And they will normally change as we become aware of new information and gain a deeper understanding of the problem. If we lose sight of them, we lose our way in the analytic process.

We should concentrate our analytic efforts on the major factors and issues. Studying subtleties (lesser factors and issues), incorporating them into our analysis, and weighing their impact on the situation and its possible outcomes are usually a waste of time because subtleties never play a significant role. We should analyze subtleties only to the point where we recognize them for what they are. “But subtleties,” you say, “can be important.” I disagree. If a subtlety is important, it is, by definition, no longer a subtlety; it’s a major factor or issue and should be treated as such.

Oddly enough, people have great difficulty in articulating major factors in a given situation. What they tend to do is identify factors that come immediately to mind, that is, factors that are important to them but are not necessarily a driving force in the situation. Identifying major factors is not a congenital skill but is acquired only through practice and trial and error. The more one does it the better one does it.

The first insight, therefore, is to create at the outset and maintain throughout the problem-solving process a list of major factors and issues, adding and deleting items as necessary.

The second insight relates to the two fundamental modes of analysis. At any point in the analytic process, from the very beginning to the very end, we are in one of two modes: convergent or divergent.

Convergence means bringing together and moving toward one point. Whenever we take a narrower view of a problem, focusing our mind on a single aspect of the puzzle or eliminating alternative solutions, we are in a convergent mode. Convergence is the opposite of divergence, which means to branch out, to go in different directions, from a single point. Whenever we take a broader view of a problem, whether by examining evidence more thoroughly, gathering new evidence, or entertaining alternative solutions, we are in a divergent mode.

While divergent thinking opens the mind to new ideas and thoughts, convergent thinking closes the mind by viewing a problem ever more narrowly until it focuses on—and produces—a single solution. An apt simile is a camera lens that can be adjusted to broaden the field of view around a subject (divergence) or to zoom in till the subject fills the aperture (convergence).

Both divergence and convergence are necessary for effective problem solving. Divergence opens the mind to creative alternatives; convergence winnows out the weak alternatives and focuses on, and chooses among, the strong. Without divergence, we could not analyze a problem creatively or objectively; without convergence, we would just keep on analyzing, never coming to closure. It is therefore vital to effective problem solving that the analyst be prepared and able to shift back and forth between divergent and convergent approaches easily and at will, using each mode to its best effect as the problem-solving process dictates.

What is more, our conscious awareness of (1) the diametrically opposite roles of convergence and divergence and (2) which mode we are in at any given moment in the analytic process will, by itself, greatly enhance our ability to solve problems.

Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult for humans to shift back and forth between these two ever-opposite, ever-warring approaches. Most of us are not inherently good divergers; divergence is not one of our instinctive processes. Indeed, most of us habitually resist divergence —sometimes passionately, even angrily.

One unambiguous symptom of our convergent tendency is the difficulty most humans have in trying to brainstorm. Most people use the word “brainstorm” to mean sharing ideas about something, as in “Let’s get together tomorrow morning and brainstorm your proposal for the new project.” “Brainstorm” has thus come to mean “discuss” and usually amounts to nothing more than each of the participants presenting and arguing over his or her individual views. That is not what I mean when I say “brainstorm.” By brainstorm, I mean the freewheeling process of generating ideas randomly and spontaneously without worrying about their practicality. It’s usually done in a group of people. The fact that most people are resistant to brainstorming (in my experience, resistance appears to rise with one’s level of education) tells us how deeply rooted and dominant the convergent tendency is in our mental machinery and, by the same token, how damaging it can be to effective problem solving.

Have you ever read a book or article or paper on how to converge? Have you ever seen a TV program on “New Horizons in Mental Convergence”? How many courses have you heard of that teach convergent techniques, what we might call “ways of getting to the point”? None, of course. Humans don’t need to be taught how to converge. It comes naturally. But, there are literally hundreds of books, articles, videotapes, lectures, and courses on how to diverge, how to open the mind, how to brainstorm, how to generate creative alternatives. What does that tell us? That divergence doesn’t come naturally; we have to be taught how to do it. It tells us that, when it comes to diverging, humans are in trouble and need help.

While problems come in all varieties, shapes, and sizes, each can be categorized in terms of the roles that fact and judgment play in analysis of the problem. This categorization, represented in Figure 2-1, is called the “Taxonomy of Problem Types.”

Figure 2-1 shows, and common sense tell us, that there is an inverse relationship between the number of facts and the amount of judgment required to solve a problem. Moving to the right on the diagram, the fewer facts we have, the more judgment is required. Moving to the left, the more facts—the less judgment. From this relationship we can define four basic types of problems:

Simplistic

There is only one answer.

There is only one answer.

Examples: Who is buried in Grant’s tomb?

Who is the governor of New York?

Deterministic

Again there is only one answer, but it is determined by a formula.

Again there is only one answer, but it is determined by a formula.

Examples: What is the area of a square whose side is 20 feet?

If the circumference of a tire is 50 inches, how many revolutions must the tire make to travel one mile?

FIGURE 2-1

Random

Different answers are possible, and all can be identified.

Different answers are possible, and all can be identified.

Examples: Which of the candidates will win the election?

Which of the builders who submitted a bid will get the contract?

Indeterminate

Different answers are possible, but, because all or some are conjectural, not all possible answers can be identified.

Different answers are possible, but, because all or some are conjectural, not all possible answers can be identified.

Examples: How will permitting gays to serve in the military affect the next presidential election?

What are the prospects for U.S.-Russian relations?

In the case of the simplistic problem, no judgment is needed as there is only one answer—one fact. If we don’t know that fact, we can’t solve the problem.

In the deterministic problem, to get the answer, we must have all of the data as well as the correct formula. If either is lacking, the problem is insoluble. Again, judgment is not a factor unless we are required to speculate about either the data or the formula, in which case the problem becomes indeterminate.

In the random problem, because different answers are possible, judgment enters into the solution, but its role is limited by the fact that all possible answers are known.

In the indeterminate problem, judgment is unlimited, because not only are all possible answers not known but they are also conjectural.

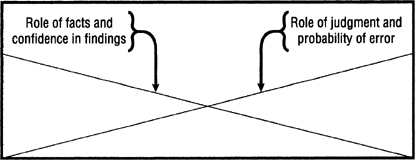

As Figure 2-2 shows, the relationship between the number of facts and the amount of judgment in any analysis is inverse. As the amount of needed facts decreases, the role of judgment increases.

There is also an obvious and direct correlation between the role of judgment and the probability of error. The more judgment we use in analyzing a problem, the greater is the likelihood of our making an error in our findings.

It follows then that, as the probability of error increases, our confidence in our findings must decrease. BUT IT DOESN’T! The human mind does not willingly or usually lose confidence in its conclusions, no matter what the circumstances. It is another of those curious human mental traits that mislead our thinking.

As I said earlier, cognitive experiments have shown that, even when the explanation we come up with doesn’t represent the evidence very well, we use that explanation anyway and feel comfortable doing so. What’s more, we defend that explanation in the face of strong contrary evidence, which we rebut with irrelevancies and sophistries. Regardless of the type of problem we are analyzing—simplistic, deterministic, random, or indeterminate —and regardless of how conjectural and subjective our analysis and its conclusions may be, we tend to defend our findings with the same high confidence.

FIGURE 2-2

And that is our third insight, to be wary of conclusions that are based largely on judgment, not facts. And if you are the author of those conclusions, take pains to couch them in language that accurately conveys the degree of your confidence in them. To do otherwise is, frankly, dishonest both to ourselves and to those who base decisions on our analysis.

The fourth insight is a basic rule that, when we have finished using any analytic structuring technique, we always do a “sanity check” by asking ourselves, “Does this make sense?” If the analytic result is reasonable, we’re probably okay. But if our intuition tells us something doesn’t seem right, we should go back and reexamine or completely redo our analysis.

Experiments in group process have shown that, in most circumstances, the analytic power of a group of analysts is greater than that of any of its single members. For that reason, the group’s consensus judgments are likely to be more accurate than the judgments of any individual member. Yet when a group of people sits around a table and analyzes a problem, rare is the group member who believes that the other members collectively know more about the problem, understand it better, and can come up with a better solution than that member can, particularly when that member’s opinion is at odds with the group’s.

Recruit five to seven people to participate in this exercise.

Give each individual the following list of eight sports.

Motorcycle racing

Horse racing

Sky diving

Mountain climbing

Boxing

Scuba diving

College football

Hang gliding

Each individual, working alone, ranks the sports according to the danger of injury to the participant.

When all members of the group have completed their individual rankings, the group assembles and, working together, again ranks the eight sports, producing a consensus list.

When the group’s consensus list is completed, turn to page 315 and, using the Sample Grading Matrix for Ranking Sports Risks, determine which of the lists is most accurate, the group consensus list or one of the members’ individual lists.

BEFORE CONTINUING, DO THE RISKY SPORTS EXERCISE.

BEFORE CONTINUING, DO THE RISKY SPORTS EXERCISE.

Did the results of the grading bear out the statement that a group’s consensus judgment is usually more accurate that the judgments of any individual member? If not, your group was the exception to the rule.

The varied and subtle ways in which humans interact to render groups of two or more dysfunctional spawned, years ago, an entire field of psychology that seeks to understand and explain group behavior and to find systematic ways of making human interactions more productive and effective. That research has made significant progress in unearthing the causes of group dysfunction and prescribing remedies. I strongly urge anyone who has occasion to work as a member of a problem-solving group to obtain training in group process. The insights gained will be of utmost help in making the members contribution more meaningful and making the group as a whole more effective.

A host of things—such as individual mind-sets, conflicts over who is in authority, domination by a clique, lack of group focus—can decimate the effectiveness of a group as, of course, can all of the mental traits described in Chapter 1. These interactions within the group tend to divide and confuse its members and to defeat their common purpose.

This is where structuring analysis can help, by organizing in a sensible, informative way the problem being analyzed. Structuring group analysis facilitates the exchange of ideas and the examination of alternatives that are necessary for building a consensus. Because group analysis tends to jump erratically from one topic to another as members press for acceptance of competing ideas, a principal beneficial effect of structuring is to help the group perceive the problem’s full dimensions, to focus its attention on individual aspects of the problem, and to keep track of where the group is in the analytic process.

Training each member of the group in the analytic techniques presented in this book will bring great benefits. The analytic empowerment that structuring affords the individual members is multiplied many times by the collective empowerment of the group, which is transformed into a powerfully creative and effective problem solver.