BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE DOWN WHAT THE PROBLEM IS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE DOWN WHAT THE PROBLEM IS.Remember the anecdote about the guy who thought his water bed was leaking? He defined the problem as “How can I fix the leak?” His analysis was guided by that definition—by that statement—of the problem. As it turned out, he had defined the problem incorrectly. He should have asked, “What is the source of the water on my blanket?” He should have made a distinction between the problem and its symptoms. Had he done so, his analysis would probably have considered alternative sources and revealed the source to be not the water bed but a leaky drain in an upstairs bathroom. How we define a problem usually determines how we analyze it. It sends us in a particular direction. And how we analyze a problem—the direction we take —absolutely determines whether we find a solution and what the quality of that solution is.

We frequently discover, based on information and perceptions gained midway through the analysis, that the initial problem statement was far off the mark. We can find examples all around us of people whose narrow definition of a problem caused their analysis to be shortsighted, overlooking alternative and possibly more beneficial solutions. Take the case of two parents concerned about their teenage son’s poor grades in high school.

FATHER: “He just doesn’t apply himself.”

MOTHER: “I know. He really isn’t interested. His mind wanders.”

FATHER: “I’m tired of harping about it all the time.”

MOTHER: “Me, too. It doesn’t seem to have any effect.”

FATHER: “Maybe he needs tutoring in how to study.”

MOTHER: “Lord knows it wouldn’t hurt. He has terrible study habits.”

FATHER: “I’ll call the school tomorrow and arrange something.”

MOTHER: “Good. I’m sure it will help him.”

The parents are pleased. They have defined the problem, arrived at a solution, and are taking corrective action. But are “lack of interest” and a “wandering mind” really the core problem? Will tutoring the son in how to study resolve it? Perhaps. But the parents may be addressing only symptoms of a deeper problem. Chances are the son himself doesn’t know what the problem is. He knows only that he isn’t motivated to study. But why isn’t he? What is the real problem?

Here’s another example:

The parking lot outside an office building is jammed with workers’ cars. Management decide to tackle the problem, so they convene a working group and charge it with devising different ways to redesign the parking lot to hold more cars. The working group does its job, coming up with half a dozen different ways to increase the lot’s capacity.

In this case, management defined the problem as how to increase the lot’s capacity, and the solutions they sought were accordingly restricted to that statement of the problem. Nothing wrong with that, is there? After all, the lot is jammed. Obviously, more parking space is needed.

But there are other ways to view (state) the problem, such as how to reduce the number of cars in the parking lot. (Options for doing that might be carpooling, moving elements of the company to other locations, and eliminating jobs to reduce the number of employees.)

Let’s do an exercise.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has discovered volatile organic compounds in effluents from a processing plant of the Algona Fertilizer Company in Algona, Iowa. These toxic waste products bypass the city of Algona but are carried into the East Fork Des Moines River, a tributary that feeds into Saylorville Lake, the principal source of water for Des Moines, a city of more than 300,000 people. The Des Moines city council, through news media and political channels, is putting enormous public pressure on state and federal environmental agencies to shut down the Algona plant. Environmental action groups, with full media coverage, demonstrated yesterday in front of the Iowa governor’s mansion demanding immediate closure of the plant. Local TV news and talk shows are beginning to focus on the issue. The company’s executive board has convened an emergency working group to consider what the company should do.

Take a moment and write down on a sheet of paper what you think “the problem” is. AND DON’T CHEAT BY NOT WRITING. You’ll miss the full benefit of this book if you don’t do all the exercises. So ponder the question for a minute or two and then write down what you think “the problem” is.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE DOWN WHAT THE PROBLEM IS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE DOWN WHAT THE PROBLEM IS.

As you may have discovered, there’s more than just one problem here, because the problem changes depending on whose perspective or self-interest we consider. Here’s a sampling of perspectives on the Algona pollution problem:

Company management

Company employees

Company union management

Company union members

Residents of Des Moines

News media of Des Moines

National news media

The Des Moines city council

The governor of Iowa

The opposing political groups

The Iowa state legislature

People who make recreational use of the affected waterways

Farmers who irrigate from the affected waterways

Federal environmental authorities

State environmental authorities

Environmental action groups

Other fertilizer companies in the Des Moines area

Other fertilizer companies in Iowa

Other fertilizer companies in the United States

Every problem, from major ones, such as abortion and national health care, to mundane ones, such as an overdrawn checking account, can be viewed from multiple conflicting perspectives. And what drives these differing perspectives? Biases and mind-sets, those unseen killers of objective truth, determine our perspective of any problem. That perspective in turn drives our analysis, our conclusions, and ultimately our recommendations. Another constraint is that the moment we define a problem our thinking about it quickly narrows considerably. It’s those mental traits again: patterning, focusing, seeking explanations, looking for supportive evidence, and so on.

Given the tremendous influence of biases on our thinking, it makes good sense at the outset of the problem-solving process (before we begin seriously analyzing the problem) to deliberately strive to identify and examine our biases as they relate to the problem at hand. What we learn may surprise us and put us on the track to solutions.

Although identifying and examining biases is the rational, common sense thing to do and will obviously greatly benefit our analysis and lead to better solutions, I know from personal experience and from observing others that attempting to make ourselves aware of our biases is extremely difficult, if not impossible. Let’s face it, the human mind by design works to conceal the biases that drive our thinking. Circumventing that design is a formidable task.

So if identifying our biases through introspection is impracticable, what are we to do? How are we to cope with these mental traits when defining a problem?

I recommend an indirect approach, which is to restate (redefine) the problem in as many different ways as we can think of. We simply shift our mental gears into a divergent mode (more easily said than done, I realize) and start pumping out restatements without evaluating them. The key here, as in all divergent thinking (discussed in Chapter 5), is letting the ideas flow freely, without attempting to justify them.

The aim of problem restatement is to broaden our perspective of a problem, helping us to identify the central issues and alternative solutions and increasing the chance that the outcome our analysis produces will fully, not partially, resolve the problem.

Sometimes restating the problem is difficult because the original statement was poorly articulated. All the more reason, then, to more clearly define it.

One can generally gain most of the benefits of restating a problem in five or ten minutes. However, those minutes are quality time where analysis is concerned. A problem restatement session will rather quickly, almost magically, focus on the crux of a problem—the core issues—and reveal what the problem is really all about, leaving our biases in the dust, so to speak. Identifying the crux of a problem saves immense time, effort, and money in the analytic phase. Sometimes restating a problem points to a solution, though usually it shows there is more than one problem and helps identify them.

If, as is often the case, we are analyzing a problem for someone else’s benefit, it is best to generate the problem restatements in that person’s presence. Doing so in an open discussion will reveal our consumer’s prime concerns and what he or she considers to be the key issues. This will facilitate reaching agreement at the start concerning what the problem is and what our analysis will aim to find out.

Most important of all, restatements should, whenever possible, be put into writing so we—and our consumer, if the problem is owned by someone else—can study them. A record copy of the agreed-upon problem statement should be retained for reference as our analysis proceeds. Retaining it not only enables us to check from time to time to see if our analysis is on target, it also offers us protection in case our consumer complains afterward that we addressed the wrong problem. Keep in mind, however, that the goal of problem restatement is to expand our thinking about the problem, not to solve it.

There are four common pitfalls in defining problems. The first two are basic.

1. No focus—definition is too vague or broad.

Example: What should we do about computers in the workplace?

This statement doesn’t really identify the problem.

2. Focus is misdirected—definition is too narrow.

Example: Johnny’s grades are slipping. How can we get him to study harder?

Lack of effort may not be the problem. If it isn’t, pressuring Johnny to study harder may aggravate the problem.

The other two pitfalls are versions of the second.

3. Statement is assumption-driven.

Example: How can we make leading businesses aware of our marketing capabilities?

By assuming that leading businesses are unaware of these capabilities, the statement defines the problem narrowly. If the assumption is invalid, the problem statement misdirects the focus of the analysis.

4. Statement is solution-driven.

Example: How can we persuade the legislature to build more prisons to reduce prison overcrowding?

This narrow-focus statement assumes a solution. If the assumed solution is inappropriate, the problem statement misdirects the analytic focus.

There are countless ways of creatively restating problems. The following five techniques are particularly effective:

1. Paraphrase: Restate the problem using different words without losing the original meaning.

Initial statement: How can we limit congestion on the roads?

Paraphrase: How can we keep road congestion from growing?

Trying to say the same thing with different words puts a slightly different spin on the meaning, which triggers new perspectives and informative insights.

2. 180 degrees: Turn the problem on its head.

Initial statement: How can we get employees to come to the company picnic?

180 degrees: How can we discourage employees from attending the picnic?

Taking the opposite view of a problem is a surprisingly effective technique, for it not only challenges the problem’s underlying premises but directly identifies what is causing the problem. In the example, the answer to the 180-degree statement may be that the picnic is scheduled at a time when employees will be at church or are otherwise engaged in important personal activities. If so, scheduling around those activities would be one way to get employees to come to the picnic.

3. Broaden the focus: Restate the problem in a larger context.

Initial statement: Should I change jobs?

Broaden focus: How can I achieve job security?

Note that the answer to the initial statement is a yes or no and immediately cuts off consideration of alternative options.

4. Redirect the focus: Boldly, consciously change the focus.

Initial statement: How can we boost sales?

Redirected focus: How can we cut costs?

Of the five techniques, this approach demands the most thought and creativity. It is therefore the most difficult but also the most productive.

5. Ask “Why”: Ask “why” of the initial problem statement. Then formulate a new problem statement based on the answer. Then ask “why” again, and again restate the problem based on the answer. Repeat this process a number of times until the essence of the “real” problem emerges.

Initial statement: How can we market our in-house multimedia products?

Why? Because many of our internal customers are outsourcing their multimedia projects.

Restatement: How can we keep internal customers from outsourcing their multimedia projects?

Why? Because it should be our mandate to do all of the organization’s multimedia.

Restatement: How can we establish a mandate to do all of the organization’s multimedia?

Why? Because we need to broaden our customer base.

Restatement: How can we broaden our customer base?

Why? Because we need a larger base in order to be cost effective.

Restatement: How can we become more cost effective?

Why? Because our profit margin is diminishing.

Restatement: How can we increase our profit margin?

A principal problem has emerged: How to obtain a mandate to do all of the organization’s multimedia projects.

As is evident from these examples, restating a problem several different ways is a divergent technique that opens our mind to alternatives. Restating a problem invariably serves to open it up, revealing important perspectives and issues we otherwise might have overlooked.

Let’s do another problem restatement exercise.

Consider this question: Should gays be permitted to serve in the military? Does this question accurately address “the problem”? What is the problem? Rephrase the question in at least a dozen different ways and see how doing so affects your perception of the problem and how you might analyze it.

BEFORE CONTINUING, RESTATE THE QUESTION IN AT LEAST A DOZEN WAYS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, RESTATE THE QUESTION IN AT LEAST A DOZEN WAYS.

A valuable tip when restating problems is to make them simple, positive, and in active voice. The mind works more easily and quickly with simple, positive, active-voice sentences than with complex, negative, passive-voice sentences. Let me demonstrate with examples.

How many variable health insurance programs have been adopted by privately owned companies in the metropolitan Washington, D.C., area, including the more densely populated municipalities and counties of northern Virginia, with from 50 to 1,000 employees with profits greater than $1 million but not less than $500,000 during FY92 compared with health insurance programs adopted by larger companies in the Baltimore area with profits less than $500,000?

It’s a struggle to wade through this statement, however accurate and comprehensive it may be. The information it contains may well be precisely what the “owner” of the problem believes he or she wants to know, but surely there’s a simpler way to express it.

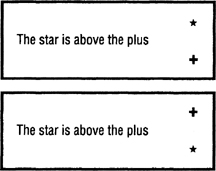

In The Universe Within, Morton Hunt describes an experiment conducted at Stanford University by Herbert Clark and a colleague that demonstrates that we humans take longer to process a negative thought than a positive one. The subjects of the experiment were shown cards like those in Figure 3-1 and were asked to say as quickly as they could whether the statement on each card was true or false. Try it yourself. It took them two-tenths of a second longer to reply to the false statement than to the true one. The explanation offered by Clark and his colleague was that, when we seek to verify a statement, we instinctively assume it is true and try to match it against the facts. If they match, we do no further mental work. If they don’t, we take the extra step of revising our assumption, thus answering a trifle more slowly. It thus takes half a second or more longer to verify denials than affirmations. We seem programmed to think more readily about what is rather than what is not.

FIGURE 3-1

This phenomenon is easily demonstrated. Read the following sentences, pausing briefly between them.

Is the ball in the bottle red?

Is the ball not in the bottle red?

Did you feel your mind scramble for a fleeting moment at the end of the second sentence to make sense of it? Negatives can do that to our minds so easily.

If negatives give us pause, look what a double negative can do:

Is the ball that is not in the bottle not red?

Huh?

Just as a simple, positive statement is easier to deal with mentally than a complex, negative one, so a statement in passive voice takes longer to process than one in active voice. That’s because the mind’s basic linguistic programming interprets and forms sentences in terms of actor-action-object, not object-action-actor. When children first begin speaking, they say, “Tom throws the ball,” not “The ball is thrown by Tom.” Of course, children quickly learn to make sense of passive voice, but, to do so, they first have to mentally rearrange the sentence to identify the actor, the action, and the object. By the time we’re adults, our minds have become adept at forming and interpreting complicated statements in passive voice. Nevertheless, our mental linguistic machinery, which is hardwired into the brain, doesn’t change. When the object in a statement comes first, the mind must still set the object aside until the actor and action become known. See if this isn’t the case as you read the following sentence:

The mind instinctively assumes that the first object in the sentence (the fan) is the subject, the actor, but the verb instantly reveals that the fan is the object instead. Can you sense your mind rearranging the parts of the sentence? Read the sentence again:

Note how much easier it is to interpret the active-voice version:

The reason is that no rearranging is necessary; the mind immediately goes about the business of interpretation.

The slight difficulty we have with passive voice probably stems from the mind’s built-in propensity to view the world in terms of cause-and-effect relationships. Thus, the mind is programmed (hardwired) to see cause first and effect second. But passive voice puts effect ahead of cause, so the mind has to reverse their order to interpret the statement.

Worrying about the phraseology of a problem statement may seem trivial, but I assure you it isn’t. As I said at the beginning of this section, how we define a problem determines how we analyze it. The wording of that definition is therefore crucial, and anything we can do to clarify and simplify it is significant.

Jerome Robbins, in his script for Leonard Bernstein’s musical West Side Story, captured the essence of problem restatement in the scene where gang members are bemoaning their lot as social misfits. Pointing to one of their members, they restate his problem several ways to reflect how various misguided social workers had defined it:

The trouble is he’s lazy.

The trouble is he drinks.

The trouble is he’s crazy.

The trouble is he stinks.

The trouble is he’s growing.

THE TROUBLE IS HE’S GROWING!

So that’s the problem! He’s growing!