BEFORE CONTINUING, SORT THE BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION.

BEFORE CONTINUING, SORT THE BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION.Sorting—what I do in grouping jigsaw puzzle pieces —is the most basic structuring technique. For that reason, one would think we could give it short shrift here and move on to techniques less well known. Unfortunately, sorting is both underused and misused. Some of us never sort problems into their component parts. (Remember, we are instinctively disinclined to use any structuring technique.) Others of us sort, but we do it incoherently or according to misleading assumptions about the nature and similarity of the parts. All of us tend to believe that only complex problems require sorting. The fact is, analysis of even the simplest problems benefits from simple sorting.

For example: In preparing a grocery list, it facilitates shopping to group items on the list according to their location in the store. Otherwise, one’s eyes are constantly scanning the whole list to ensure that items have not been missed as one moves from one aisle to another.

Of course, as the complexity and ambiguity of a problem increase (as it moves from facts to judgment, from simplistic to indeterminate), sorting and the nature of the sorting become critical to effective analysis.

On a sheet of paper, sort the following information in whatever way you wish:

Mary is 35 years old, married, with three children. She works part time as a waitress. A Catholic, she was born in Boston, and votes Republican.

John, a bus driver, is a Presbyterian, single, and a rabid Democrat. He is 50 years old and was born in Philadelphia.

Sue was born in Pittsburgh and is a dentist’s receptionist. She is 25, a Catholic, single, a Democrat. Gloria, a Methodist, is a full-time computer programmer. Born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, she is 37, a Democrat, married, and has two children.

Bob is 26, born in York, Pennsylvania, a Baptist, married without children, a marketing specialist, and a Republican.

BEFORE CONTINUING, SORT THE BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION.

BEFORE CONTINUING, SORT THE BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION.

There are numerous ways, all of them perfectly satisfactory, to sort this information. By sorting it, we are in a position to answer any of a wide range of questions about these people. What is their average age? How many are Catholic? Which persons were born in Pennsylvania? The principle involved is the same one I use to assemble jigsaw puzzles: putting similar pieces together in groups. What could be simpler? What could be more helpful in analyzing a problem?

Another highly useful but elementary technique for organizing information is a chronology, or what Harvard professors Richard Neustadt and Ernest May call a time line in their thoroughly engaging, highly informative book Thinking in Time. (I would do their exceptional book injustice by trying to summarize its compelling contents. I therefore urge the reader to read Thinking in Time. Its method supplements very well the analytic structuring techniques I present here.)

We humans instinctively think chronologically. Read the following sentence: John and Mary had their first child in1985, met on a blind date in 1979, moved to Texas in 1981, and were married in 1980. Did your mind register a silent but nonetheless perceptible protest when you discovered that the dates were out of chronological order? Mine did. It said, “Huh?” It does that every time I stumble over information that I expect to be chronological that isn’t. At the same time I can feel my mind trying to rearrange the statements to put them in chronological order. Did yours do that? It’s an irresistible compulsion.

This compulsion to view events chronologically is related to our instinct to view the world in terms of cause-and-effect relationships. As I said earlier, the mind is programmed to see cause first and effect second. Event A causes (leads to) Event B. Naturally, then, A should precede B. If we read something that upsets the chronology, describing Event B first and Event A second, the mind, in order to interpret the report, silently reverses the events, just as it reverses the order of object and actor in passive voice.

Reports written by journalists, historians, researchers, scientists, and members of other analytic professions customarily present their findings chronologically as a means of facilitating understanding, both for the author and for the reader. Novelists and historians occasionally employ flashbacks and other nonchronological approaches as a presentational device that serves some special purpose in the author’s work. But anything that disrupts the chronology of events can, and often does, confuse the reader—as well as the author—because thinking chronologically is how our minds prefer to work.

Consider the following newspaper article in The Washington Post of June 14, 1994:

A Navajo was the first to die. Autopsies showed that both had essentially drowned, their lungs soaked with serum from their own blood. But, on May 14,1993, her fiancé, Navajo runner Merrill Bahe, 20, died too. After all, Florena Woody did have a history of asthma. Then he collapsed. His horrified sister-in-law stopped at a general store and dialed 911. And no one knew why. One day Florena Woody, 21, was healthy; the next day she could no longer breathe. Bahe began gasping for air during the 55-mile drive across the state from the couple’s trailer in Little Water, N.M., to Woody’s funeral in Gallup. Although many grieved, her abrupt death on May 9 was not alarming. Bahe paced, agitated, his skin tinged with yellow, his lips and fingernails turning blue.

Did your mind say “Huh?” or even several mega-huhs as you read this paragraph? That’s because I randomly rearranged the order of the sentences in the original article. Did you feel your mind trying to sort and rearrange the sentences to put them in chronological order as you read?

Here’s what the article actually said:

A Navajo was the first to die. One day Florena Woody, 21, was healthy; the next day she could no longer breathe. Although many grieved, her abrupt death on May 9, 1993, was not alarming. After all, Florena Woody did have a history of asthma. But five days later her fiancé, Navajo runner Merrill Bahe, 20, died too. Bahe began gasping for air during the 55-mile drive across the state from the couple’s trailer in Little Water, N.M., to Woody’s funeral in Gallup. His horrified sister-in-law stopped at a general store and dialed 911. Bahe paced, agitated, his skin tinged with yellow, his lips and fingernails turning blue. Then he collapsed. Autopsies showed that both had essentially drowned, their lungs soaked with serum from their own blood. And no one knew why.

Clearly, chronological order is not merely important to understanding; it can be indispensable. Presented visually, as in Table 6-1, a chronology shows the timing and sequence of relevant events, calls our attention to key events and to significant gaps, and makes it easier to identify patterns and correlations among events. It allows us to understand and appreciate the context in which events occurred, are occurring, or will occur. We are then in a far better position to interpret the significance of each event with respect to the problem. Sometimes putting events in chronological order points to a solution.

“A time-line,” write Neustadt and May, “is simply a string of sequential dates. To see the story behind the issue [the problem], it can help merely to mark on a piece of paper the dates one first associates with [the problem’s] history. Because busy people often balk at looking very far into the past, we stress the importance of beginning with the earliest date that seems at all significant.” Neustadt and May urge decision makers of all shapes, interests, and venues to place greater reliance on history. “Implicitly: vicarious experience acquired from the past, even the remote past, gives such guidance to the present that [the history of the problem] becomes more than its own reward.”

We construct a chronology (time line) in two simple steps:

Step 1: As you are researching a decision or problem, make a list of relevant events and their dates, but always list the dates first.

Listing dates first facilitates constructing the chronology. Do not include obviously marginal events, but if you must err, err on the side of including them. Their true significance will likely become apparent when the chronology is completed.

Step 2: Construct a chronology, crossing off events on the list as they are included.

The chronology can be either horizontal or vertical, whichever you find easier to analyze and interpret.

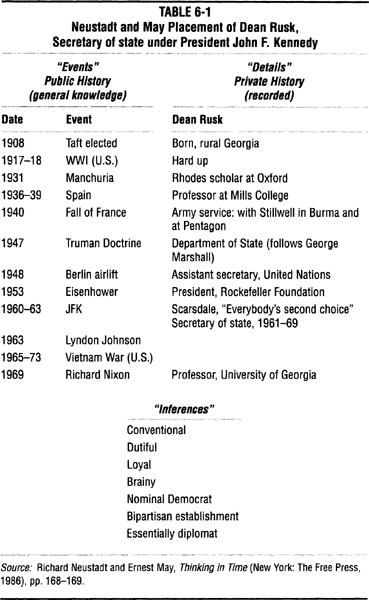

A special form of time line is what Neustadt and May call “placement,” which means arraying chronologically the events in public history and details in private life that may affect the mind-set or viewpoint of a decision maker whether the latter be a person or an organization. From this history and details we draw inferences about the decision maker’s thinking—motives, prejudices, and so on. An example of placement is that prepared by Neustadt and May of former Secretary of State Dean Rusk (see Table 6-1). Placement is treated again in Chapter 12 in the context of role-playing one’s competitors in order to gain insights into their decision making.