Imagine a mechanic trying to repair a malfunctioning engine whose components and inner workings he doesn’t understand. “Kick it!” urges a bystander. “That’ll make it work!” And kick it is what so many people do in trying to solve a problem whose internals they do not fathom. Even when we fully understand what “the problem” is, we all too often have a poor comprehension of what is causing it. Lacking that vital knowledge, we resort to that timeworn problem-solving method called trial and error with its focus glued to the first plausible corrective option we think of.

All events in life are the results, the outcomes, of previous events. Life itself is a collage of ecological cycles, all intertwining, mingling, overlapping, sharing, and competing, all linked together in countless ever-evolving chains of cause-and-effect relationships. Likewise, every problem we analyze is the product of a definable cause-and-effect system. It stands to reason, then, that identifying that system’s components—the major factors—and how they interact to produce the problem is essential to effective problem solving. Moreover, illuminating these major factors and their interactions can validate or invalidate our initial perceptions about how the system works and uncover hidden biases and mind-sets that may mislead our thinking.

Therefore, when confronted with a problem, the first questions we should ask ourselves are: What is causing this problem? How are the major factors interacting to produce this result?

There are five steps for defining and analyzing a problem’s cause-and-effect system:

Step 1: Identify major factors.

Step 2: Identify cause-and-effect relationships.

Step 3: Characterize the relationships as direct or inverse.

Step 4: Diagram the relationships.

Step 5: Analyze the behavior of the relationships as an integrated system.

Let’s take the steps one at a time. First, we identify the major factors—the engines that drive the problem. (Note: We are concerned in causal flow diagramming primarily with dynamic factors, those that expand and contract, rise and fall, etc.) Let’s consider five major factors in a typical large manufacturing business: sales, profits, research and development, marketing of new products, and competitors’ marketing of comparable products. (This is, of course, an oversimplified representation. There are many other factors involved, but I am using these five simply to demonstrate the technique.)

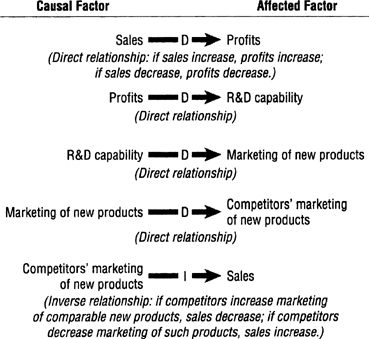

The second step is to identify the cause-and-effect linkages among the factors. To do that we use a two-column “Cause-and-Effect Table” (Figure 7-1). In the left-hand column we list the causal factors, in the right-hand column the affected factors, and we draw an arrow between them.

Sales affect profits. Profits affect R&D capability. R&D capability affects the marketing of new products. Marketing of new products affects competitors’ marketing of comparable new products. The marketing of competitive new products affects sales.

FIGURE 7-1 Cause-and-Effect Table

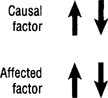

The third step is to characterize these cause-and-effect relationships as direct or inverse. If the affected factor increases as the causal factor increases and decreases as the causal factor decreases, we have a direct relationship (Figure 7-2).

If, in the opposite case, the affected factor increases as the causal factor decreases and decreases as the causal factor increases, we have an inverse relationship (Figure 7-3).

We indicate a direct relationship with a “D” and an inverse relationship with an “I” (Figure 7-4). If the affected factor is static, i.e., not dynamic, like “death” or “out of business,” we do not assign it an indicator.

In the fourth step we portray these linkages in a causal flow diagram (Figure 7-5). I recommend drawing a circle around each of the factors to highlight them visually, accentuating their distinctiveness.

FIGURE 7-2 Direct Relationship

FIGURE 7-3 Inverse Relationship

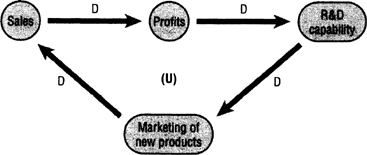

The most powerful driving force in any cause-and-effect scheme is the so-called feedback loop in which two or more factors are linked circularly in continuous interaction. The behavior of a feedback loop is significant and predictable. If, as in Figure 7-6, all of the linkages are direct relationships, or if there is an even number of inverse linkages, the loop is inherently unstable and will eventually spiral out of control—in either direction. If sales increase, profits increase, R&D increases, marketing of new products increases, causing a further increase in sales, and so on. A “(U)” signifies an unstable feedback loop, a dynamo that drives and powers the cause-and-effect system.

FIGURE 7-4

FIGURE 7-5 Causal Flow Diagram

If there is an odd number of inverse linkages, as in Figure 7-7, the loop is inherently self-stabilizing and will achieve equilibrium at some point. If sales increase, profits increase, R&D increases, and marketing of new products increases; but competitors’ marketing of new products also increases, causing sales to decrease. When sales decrease, so do profits, R&D, marketing of new products, and competitors’ marketing of new products, resulting in increased sales. And so the causal flow interactions increase and decrease cyclically. An “(SS)” signifies a self-stabilizing feedback loop, a governor that controls and regulates the cause-and-effect system.

FIGURE 7-6

FIGURE 7-7 Self-Stabilizing Feedback Loop

In the fifth and final step we analyze the behavior of the system as an integrated whole, seeking to determine which factors are the most influential. And when a problem occurs, we analyze which factor is creating the problem and how the problem might be resolved by modifying or eliminating factors or introducing new ones.

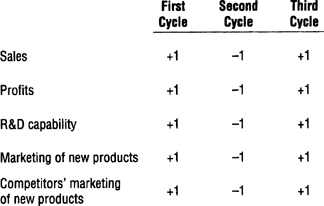

One way (sort of a sanity check) of validating whether we have accurately portrayed the cause-and-effect relationships is to add a value of +1 to any factor and see how this increment affects the system as a whole. Let’s try this method on Figure 7-7, beginning with “sales.”

If we increase the value of “sales” by 1, the value of “profits” increases by 1 because there is a direct relationship between the two factors (see First Cycle, Figure 7-8). “R&D capability” then also increases by 1, as do “marketing of new products” and “competitors’ marketing of new products.” But then in the Second Cycle the value of “sales” decreases by 1 because of its inverse relationship with “competitors’ marketing of new products.” This decrease starts a new cycle, decreasing the value of each of the other factors by one, which causes the value of “sales” in the Third Cycle to increase by one, triggering yet another cycle. The cycles show how the value of each factor alternates between positive and negative, reflecting the self-stabilizing nature of this feedback loop.

FIGURE 7-8

Construct a causal flow diagram for the following situation, indicating with “D” or “I” whether the cause-and-effect relationships are direct or inverse and identifying any feedback loop(s) as unstable (U) or self-stabilizing (SS):

With the expectation of increasing its clientele and thus its sales, a shopping mall in the suburb of a large city enlarged an area of the mall’s parking lot located near a subway station used regularly by commuters to and from the city. Commuters who did not shop at the mall parked their cars in the new lot, greatly reducing the spaces available to shoppers. As a consequence, the slight increase in sales generated by the new parking spaces did not offset the cost of construction. So the mall constructed more parking areas, but again commuters used up most of the spaces.

BEFORE CONTINUING, PREPARE A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT TABLE AND CAUSAL FLOW DIAGRAM ON THE PARKING PROBLEM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, PREPARE A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT TABLE AND CAUSAL FLOW DIAGRAM ON THE PARKING PROBLEM.

The solution to Exercise 10 (page 321) shows one representation of these cause-and-effect relationships. As space for public parking at the mall increases, nonshopping commuters make greater use of mall parking (direct relationship), parking spaces available to shoppers decrease (inverse relationship), sales by stores in the mall decrease (direct relationship), and construction of new public parking spaces increases (inverse relationship). This is an unstable feedback loop indicating that the problem will continue to worsen until it ultimately reaches a crisis stage.

Portray in two stages the causal flow dynamics of the “Algona Pollution” problem (Exercise 3 on page 61). First, prepare a cause-and-effect table listing the major factors, showing how they interacted with one another, and indicating whether those relationships were of a direct or inverse nature. Second, construct a causal flow diagram illustrating these relationships.

BEFORE CONTINUING, PREPARE A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT TABLE AND CAUSAL FLOW DIAGRAM ON THE ALGONA POLLUTION PROBLEM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, PREPARE A CAUSE-AND-EFFECT TABLE AND CAUSAL FLOW DIAGRAM ON THE ALGONA POLLUTION PROBLEM.

The solution to Exercise 11 (pages 322-23) presents my interpretations. Each major dynamic factor from “toxic effluents” through “corrective action by Algona management” interacts, one to the next, in a direct relationship. The link, however, between “corrective action by Algona management” and “toxic effluents” is an inverse relationship. Thus, we have a self-stabilizing feedback loop. The more pressure mounts on Algona management to take corrective action to clean up the effluents, the more corrective action it takes, and the fewer effluents there are. The fewer effluents, the less contamination, and so on.

Try your hand at diagramming the starvation scenario in Somalia in 1983-84.

Part 1: Consider four major factors: starvation, media coverage, foreign assistance, and local warlords profiteering from the foreign assistance. Link the four factors together in a feedback loop and annotate the linkages with a “D” or “I” to indicate direct or inverse relationships. Is this a stable or unstable loop?

BEFORE CONTINUING, DRAW ON A PIECE OF PAPER A CAUSAL FLOW DIAGRAM LINKING THE FOUR FACTORS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, DRAW ON A PIECE OF PAPER A CAUSAL FLOW DIAGRAM LINKING THE FOUR FACTORS.

Part 2: Revise the diagram to include three additional factors:

The presence of aid workers

Violent attacks on aid workers by warlord forces

The presence of U.S. military forces

Identify as many feedback loops as you can, and indicate whether the linkages are direct or inverse relationships. What is the overall impact on the situation of the inclusion of these three factors?

BEFORE CONTINUING, REVISE THE DIAGRAM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, REVISE THE DIAGRAM.

Part 1 of the solution to Exercise 12 (page 324) shows what you should have drawn. As all of the linkages are direct relationships, the loop is unstable and, as history showed, spiraled out of control. The diagram shows that as starvation increased, media coverage increased, prompting increased foreign assistance and warlord profiteering, resulting in increased starvation, increased media coverage, and so on.

There are countless different ways to diagram cause-and-effect relationships. Part 2 of the solution to Exercise 12 presents one rendition of the Somalia situation. The diagram identifies four feedback loops:

Starvation

Media coverage

Foreign assistance

Starvation

Starvation

Media coverage

Foreign assistance

Aid workers present

Warlord attacks on aid workers

U.S. military presence

Warlord profiteering

Starvation

Warlord attacks on aid workers

U.S. military presence

Warlord attacks on aid workers

Unstable

Starvation

Media coverage

Foreign assistance

Warlord profiteering

Starvation

Note that foreign assistance and U.S. military presence have opposite relationships with warlord profiteering. This had a stabilizing effect on warlord profiteering and on the situation as a whole. However, the deaths of a number of U.S. servicemen with the peacekeeping forces in Somalia ultimately led to the withdrawal of U.S. forces. How would you diagram the factor “U.S. military fatalities”?

BEFORE CONTINUING, REVISE THE DIAGRAM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, REVISE THE DIAGRAM.

Part 3 (page 325) shows how I would diagram “U.S. military fatalities.” As warlord attacks increased, U.S. military fatalities increased, causing a reduction in U.S. military presence. (The deaths led to strong U.S. public and congressional disenchantment with the U.S. administration’s policy in Somalia and prompted the eventual withdrawal of U.S. forces.) This reduction emboldened the warlords, who increased their attacks on workers and U.S. military forces, causing further casualties. This was an unstable feedback loop.

In the larger picture, the reduction in U.S. military presence encouraged increased profiteering by the warlords, causing increased starvation, and so on. The feedback loop linking all eight factors was thus rendered unstable.

Causal flow diagramming does for a problem-solving analyst what disassembling a wristwatch does for a watch repairman. The repairman lays out on his workbench all of the watch’s components so he can (1) understand the internal mechanisms and how each piece interacts with the others, (2) determine what is causing the watch to malfunction, and (3) identify ways to repair it.

A causal flow diagram likewise establishes a visual framework—a structure—within which to analyze a cause-and-effect system.

This diagram:

Identifies the major factors—the engines—that drive the system, how they interact, and whether these interactions are direct or inverse relationships or form feedback loops.

Identifies the major factors—the engines—that drive the system, how they interact, and whether these interactions are direct or inverse relationships or form feedback loops.

Enables us to view these cause-and-effect relationships as an integrated system and to discover linkages that were either dimly understood or obscured altogether.

Enables us to view these cause-and-effect relationships as an integrated system and to discover linkages that were either dimly understood or obscured altogether.

Facilitates our determining the main source(s) of the problem.

Facilitates our determining the main source(s) of the problem.

Enables us to conceive of alternative corrective measures and to estimate what their respective effects would be.

Enables us to conceive of alternative corrective measures and to estimate what their respective effects would be.

Causal flow diagrams can be particularly helpful in bringing to light how different analysts working on the same problem view it. If each analyst constructs a diagram representing the causal flow system and submits it to the others for study and comparison, the ensuing discussion will quickly and clearly reveal how and where their perceptions differ and what their underlying assumptions are. This knowledge will greatly enhance understanding of the problem and of possible solutions.

Causal flow diagramming is, of course, a form of modeling and can be as simplistic or complex as the analyst desires. I prefer to make such diagrams only as complicated as needed to understand the major forces at work. Going beyond that, albeit interesting and even entertaining, can be counterproductive, making the analyst aware of intricate causal relationships that, while perhaps accurate (but perhaps not), add only complexity and ambiguity to the overall picture.

Keep in mind that the principal purpose of diagramming is to establish a basic structure for analyzing the major driving factors, not to replicate in precise detail every dynamic of the problem situation. What we are seeking is insights into possible solutions. Once we acquire those insights, the diagram has served its purpose and may be set aside.

If, on the other hand, you have need of a diagram that portrays in detail the inner workings of the problem situation, indicating how the system as a whole reacts to changes in one factor or in a combination of factors, I recommend you look to literature and training courses in the field of operations research.