BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE ON A PIECE OF PAPER WHAT YOU THINK THE PROBLEM IS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE ON A PIECE OF PAPER WHAT YOU THINK THE PROBLEM IS.Read the following problem and answer the questions.

A few days before Thanksgiving—the busiest grocery shopping period of the year—a bakery that produces specially prepared bread with a unique blend of ingredients for several grocery chains is having serious problems. Scores of loaves are emerging from the ovens either burned or dark and crusty. In either case, the loaves are worthless.

This bread is produced by three crews of workers, all of whom work the late shift from 4.00 P.M. till midnight. Each crew is responsible for preparing its own dough and is equipped with its own set of five large gas ovens which are used in sequence as the dough is prepared. Each oven has a capacity of fifty loaves. Each crew produces ten batches of bread, fifty loaves in a batch. It takes five hours to produce a batch: four hours for mixing, kneading, and rising and one hour for baking. One batch is begun every hour for the first five hours of work. A crew on the midnight-to-8:00 A.M. shift packages the loaves for delivery.

Ted Swanson, the bakery’s production manager, became aware of the problem at 11:00 P.M., when he heard Fernando Rodriguez, the baker of Crew 1, shouting and cursing. Swanson rushed out of his office and found the baker and his seven-person crew frantically hauling bread pans out of an oven and emptying their blackened contents into several large garbage cans.

“What the hell’s going on, Fernie?”

“What happened?” asked Swanson.

“Damned if I know. The oven is set at three hundred fifty degrees, right on the button, and when we put the pans in an hour ago the dough looked fine.”

Wanda Parnell, who ran the warehouse, had been attracted by the commotion and came out of her office to see what was going on. She literally smelled trouble and, being the bakery’s union representative, liked to keep herself informed when problems arose.

“Maybe the thermostat is malfunctioning,” said Swanson. “I’ll call the service company and have them send someone over to check it out. Which oven is it, number three?”

Swanson patted him on the shoulder. “Don’t worry about it. There’s a first time for everything. Chalk it up to experience.” Swanson turned to leave. “Let me know what the serviceman says. In the meantime, let’s turn off that oven. If it’s acting up, we’ll need to fix it right away. We can’t afford downtime during the Thanksgiving rush.”

As Swanson entered his office, Henry Willis, the bakery manager, hailed him from the adjoining room. “Hey, Ted! What’s all the ruckus about?”

“Oh, nothing. Fernie’s crew burned a batch of bread.”

“That’s not like them,” said the manager, frowning. “What happened?”

“Don’t know. I’m having the oven’s thermostat checked. I’ll let you know what they find.”

“Did you shut the oven down?”

“Yep, until we determine if it’s the thermostat.”

“Is this going to cause a problem meeting orders?”

“It shouldn’t. Even if the thermostat is bad, you know we can replace it in ten minutes and have the oven back up and running in another twenty.”

“All right,” said Willis. “Keep me posted.”

“You got it.”

Twenty-five minutes later the oven technician arrived, checked the oven’s heat control mechanism, and reported there was nothing wrong with it. Willis, Swanson, and Rodriguez discussed the matter briefly and decided to reheat the oven and bake another batch to replace the burned loaves.

“What is it?” Swanson sprang from his chair and followed Parnell out into the bakery.

“Crew One overbaked another batch, and now Crew Three has done it, too, though not as bad.”

The two jogged past the Crew 1 area, where Fernie and his people were again hauling out blackened loaves, and arrived at the Crew 3 area. There they found Bobby Lanham, the crew’s baker, glowering, his hands clasped behind him, silently shaking his head, looking over worktables covered with fifty pans of hot bread just removed from Crew 3’s number four oven.

“What’s the problem, Bobby?” asked Swanson.

“Overbaked ’em. I can’t explain it. Fernie’s burned two batches, and now I’ve almost done the same. They aren’t burned like his, but they’re too crusty to ship to the stores. Okay with you to pitch ’em?”

“Might as well,” said Swanson with obvious resignation.

At that moment Willis joined them. “Another ruined batch?” he said, gazing unhappily at the dark brown loaves.

“Three batches,” replied Swanson, pointing to Femie’s area.

“Three!” he exclaimed. “What the hell is going on around here?” The look on his face and the inflection and tone of his voice implied he suspected these were not accidents or oversights.

The others looked at him, first with surprise, then with a mixture of concern and resentment. “We don’t know yet,” said Swanson, “but we’ve gotta find out pronto.” He started walking toward his office. I’m calling the technician back here. There’s got to be something wrong with these ovens. Maybe the gas pressure’s fluctuating. Let’s shut both those ovens down, and don’t reheat Crew One’s number three. We need some answers first.”

Twenty minutes later, Willis entered Swanson’s office and sat down. “I don’t like it, Ted. Not one bit. Something’s going on here. Experienced bakers don’t accidentally overbake bread. Not like this. Not three batches.”

“What are you suggesting? Sabotage?”

“Impossible! Fernie and Bobby would never do that.”

“Oh, yeah? Bobby’s a hothead and has made his unhappiness with my management very clear over the past few weeks, and he and Fernie are best friends.”

Swanson could not take issue with either point. The Bakery Workers Union had been putting a lot of pressure on Willis concerning the contract renegotiations in two weeks. In a meeting with Willis and Swanson just two days before, Wanda Parnell had presented the union’s demands for a significant increase in employee benefits including additional sick leave. Willis had been dead set against granting any further benefits, insisting the company couldn’t afford it.

Willis continued, “What better time to foul things up than just before Thanksgiving? I’d fire the both of them if I had proof.”

“There could be other explanations,” said Swanson.

“Like what?”

“You know bread making. Could be the oven racks turning too slowly, too much voltage to the oven blowers, maybe bad yeast or other stale ingredients. Lots of things the bakers have no control over.”

“All right. Let’s look at the facts. Bobby’s been wound up tight as a drum ever since I fired Juan Menendez two weeks ago for being drunk on the job. That was the third time I caught him. I had warned him twice before, but the third time… that was the last straw. So Bobby keeps yammering about no evidence, no blood test, like I was a cop who arrested Menendez for drunk driving and forgot to read him his rights. This is a business, not a police station. And I know a drunk when I see one. Now Bobby’s got the crews all steamed up about it, including Fernie.”

“Okay, you’re right about Fernie,” said Swanson. “He has spoken to me a few times about Menendez, but always polite and reasonable, not high-strung like Bobby.”

“And didn’t Fernie help Bobby hold a special union meeting over the weekend to discuss the benefits package? Remember what one of the guys on Crew One said to you Monday?”

“I remember. The union’s gonna get the new benefits come hell or high water.’ “

“Right. It wouldn’t surprise me if Crew Two burns the next batch. Union people call it solidarity!”

“Oh, come on, Hank. Frank Moreau? Neither he nor anyone on his crew would deliberately do such a thing. Frank is antiunion.”

“But still a union member!” said Willis, shaking his finger.

“Frank explained all that. He had to join if he was to build teamwork on his crew.”

“Baloney. I was a baker for ten years, and I never felt obliged to join the damn union.”

“Times are different.”

“Did you know Menendez was here yesterday?”

“No! Where?”

Swanson shrugged.

“Frank Moreau. What do you make of that little rendezvous?”

Swanson was shocked and remained silent for a moment. Then he got up. “I’m gonna check on the ovens. The technician is looking at them right now. I’ll speak with Frank about all this.”

“While you’re at it,” said Willis smirking, “ask him how his leg is.”

“His leg? What’s wrong with it?”

“He claims he dropped a sack of flour on his foot this morning unloading that shipment from the new supplier. Nothing broken, he said, but he was limping badly… or pretending to limp. Maybe he’ll file for workers’ comp.”

Swanson shot him a disdainful look and departed.

Swanson found Frank in the Crew 2 area checking the temperature gauges on his ovens. “So what’s your opinion, Frank? Are the gauges going funny?”

“Nope. The service guy just finished his tests. The gauges are fine and so are the rack and blower mechanisms. And if the problem was pressure fluctuations on the gas lines, then all of the ovens would have been affected.”

“How’s the leg?”

“Could be better. Damn sacks. I was helping Wanda unload the truck this morning. She usually forklifts the entire load into the warehouse, but at the end of our shift yesterday Bobby gave her all kinds of hell because there was no more flour. With the Thanksgiving rush and one sack for every two batches, it’s a wonder we didn’t run out sooner. So I helped her move some sacks directly to the crew areas so each would have enough for the day’s baking.”

“Any problems?”

“Nope, but I don’t recommend dropping one of those hundred-pound babies on your foot. The shipment arrived just in time. It was two days late, you know.” Moreau laughed. “Did Willis think the union was behind the delay? Like maybe someone pulled strings with the teamsters?”

Swanson shook his head and frowned. “Of course not.” But he knew Moreau was right. Willis suspected union interference.

“I’ll bet he did. It was a close call. Like always, we use up old ingredients before starting with the new. When we finished yesterday, I had two of the old sacks left, Bobby was down to one and a half, and Fernie had only one. I could see Willis pacing up and down in his office yelling into the phone to the shipper. Willis knew we were right on the edge of disaster. He probably thinks we planned to run short just to make his life miserable.”

“Can you blame him? It’s Thanksgiving, our busiest time.”

“I suppose not. But the mood around here is pretty nasty. I don’t think the crews would feel sorry for Willis if this place were shut down for a day or so.”

“Whaddaya mean by that?” Swanson was shocked. It sounded like a threat.

“I mean people are angry. They don’t get the standard benefits other bakeries give.”

“Are you siding with the union on this thing?”

Moreau scowled. “What’s the union got to do with it? I thought we were talking about the mood around here. People want what they think they’re entitled to. The union’s just taking advantage of it, like unions always do. You know I’m not fond of unions. But the facts are the facts. Willis better wake up or he’s going to have real problems, and his firing Menendez didn’t help the situation.”

“Are there really hard feelings about the Menendez thing?”

“Naturally. He was very popular with the crews. And he was older, kind of a father figure for some of the younger people. Willis should have thought of that.”

“I hear Menendez stopped by here yesterday. Did you talk to him?”

“Would it make a difference if I did?”

“That depends on what you talked about.”

“Well, for your information, we just talked. Nothing special.”

“Did he talk with anyone else?”

“Look, Ted, I’m not your informant. If you want to know that, ask them.” Moreau abruptly turned his back and redirected his attention to the ovens.

Swanson checked his watch. It was a quarter of one. He hurried away to talk with Willis.

What’s the problem? What caused the three batches to be overbaked? What was behind it? Was it accidental or intentional? What do you think? On a sheet of paper write what you think “the problem” is. Don’t write more than one problem statement!

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE ON A PIECE OF PAPER WHAT YOU THINK THE PROBLEM IS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE ON A PIECE OF PAPER WHAT YOU THINK THE PROBLEM IS.

Most people who work a problem of this type do all of the analysis in their heads, thinking it through, reasoning out the different possible explanations, and focusing on the first one they can confidently defend. But would they structure their analysis? Probably not, because, as I said in the beginning of this book, most people don’t know how. Let me show you how to structure the analysis of “The Bakery” problem.

First, we think of as many different explanations as we can for the bread being overcooked. We call that diverging. We then sort the explanations (cluster them) into definable groups, which we’ll call categories, for want of a better term. As we analyze the situation, we discern four fundamental categories: human, mechanical, materials, and combinations thereof. We also discern ten basic explanations (you may have thought up more), which I have listed below by category:

Human

Sabotage

Sabotage

Careless error

Careless error

Fatigue

Fatigue

Drunkenness

Drunkenness

Flaws in the work plan

Flaws in the work plan

Mechanical

Malfunctioning of the oven temperature gauge

Malfunctioning of the oven temperature gauge

Malfunctioning of the rotating oven racks

Malfunctioning of the rotating oven racks

Malfunctioning of the oven blower

Malfunctioning of the oven blower

Malfunctioning of the gas pressure gauge

Malfunctioning of the gas pressure gauge

Materials

Spoiled or otherwise unsuitable ingredients

Spoiled or otherwise unsuitable ingredients

Combinations (of the three categories above)

Let’s examine each category. Remember, that’s what structuring analysis does: it enables us to analyze each element of a problem separately, systematically, and sufficiently.

In the “Human” category, the text did not furnish any information upon which to conclude that carelessness, fatigue, drunkenness, or flaws in the work routine would explain the overbaking. To consider these possibilities, we need to gather more information. There is, however, plenty of evidence to support sabotage. One could spin a number of plausible scenarios involving the bakery’s angry, disgruntled employees. That’s what Willis was doing. He focused on sabotage as the explanation and was interpreting each new event through the prism of that bias.

The text essentially ruled out the “Mechanical” category, but here again we could probably benefit from gathering more information.

There were a number of references, of course, to “Materials”: the ingredients used to make the bread. Three ingredients were mentioned: milk and yeast (but only once each) and flour (numerous times). What did the text say about flour?

As a matter of practice, the crews used up old ingredients (in this case, flour) before starting with the new.

As a matter of practice, the crews used up old ingredients (in this case, flour) before starting with the new.

At close of business the day before, there was no flour in the warehouse, and the crews would not have had enough that day had a shipment not been delivered that morning. Crew 1 had one sack of flour left, Crew 2 had two, and Crew 3 had one and a half.

At close of business the day before, there was no flour in the warehouse, and the crews would not have had enough that day had a shipment not been delivered that morning. Crew 1 had one sack of flour left, Crew 2 had two, and Crew 3 had one and a half.

The shipment of flour that arrived that morning was from a new supplier.

The shipment of flour that arrived that morning was from a new supplier.

The shipment was two days late; it arrived just in time.

The shipment was two days late; it arrived just in time.

Moreau helped Wanda Parnell move some sacks directly to the crew areas so each crew would have enough for the day’s baking.

Moreau helped Wanda Parnell move some sacks directly to the crew areas so each crew would have enough for the day’s baking.

Each batch of bread consumed one-half sack of flour.

Each batch of bread consumed one-half sack of flour.

Could using the new flour explain the overbaked loaves? It’s conceivable there was something wrong with the flour delivered that morning from the new supplier. We can find out by determining whether there was a correlation between use of the new flour and the incidents of overbaking. To analyze this question, I have constructed chronologies using a matrix.

As shown in Figure 8-1, a matrix is nothing more than a grid with as many cells as needed for whatever problem is being analyzed. A matrix is one of the handiest, clearest methods of sorting information. Any time I can reduce information to a matrix, I find it analytically illuminating.

FIGURE 8-1

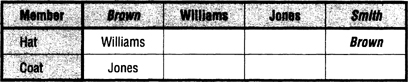

For example, a suspect in a crime is answering a detective’s questions. The detective wonders whether the answers are truthful. But there are actually four essential scenarios, which the matrix in Figure 8-2 clearly distinguishes.

FIGURE 8-2

Because each scenario (each cell) requires a different interrogation strategy (different questions, different sequences of questions, and so on), the detective would be well advised to plan the four strategies beforehand. This matrix is the perfect structuring tool for that purpose.

Like sorting pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, a matrix enables us, among other things, to:

Separate elements of a problem

Separate elements of a problem

Categorize information by type

Categorize information by type

Compare one type of information with another

Compare one type of information with another

Compare pieces of information of the same type

Compare pieces of information of the same type

See correlations (patterns) among the information

See correlations (patterns) among the information

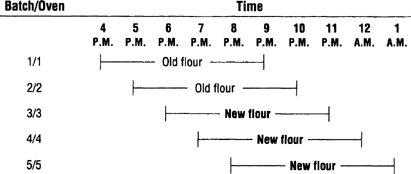

The matrices in Figures 8-3 through 8-5 show when each crew started each of its first five batches, when each batch was removed from an oven, and which batches used the new flour. Each crew prepared one batch every hour, using its ovens sequentially.

As Figure 8-3 indicates, Crew 1 had one sack of old flour left when work began at 4:00 P.M. It used that sack for its first and second batches (each batch required a half sack of flour). That means the third batch (begun at 6:00 P.M.) and each subsequent batch used the new flour. Crew l’s first and second batches (with the old flour) came out all right, but the third and fourth (using the new flour), removed from the ovens at 11:00 P.M. and midnight, were overbaked. This pattern is consistent with the new flour’s causing the overbaking.

Crew 2 (Figure 8-4) had two sacks of old flour. It didn’t begin using the new flour until the fifth batch at 8:00 P.M. If that batch were over-baked, it wouldn’t be known until the loaves were removed at 1:00 A.M. Nevertheless, this pattern is consistent with the new flour being the source of the problem.

FIGURE 8-3 Batch Chronology: Crew 1

FIGURE 8-4 Batch Chronology: Crew 2

FIGURE 8-5 Batch Chronology: Crew 3

Crew 3 (Figure 8-5) had one and a half sacks of old flour when work began at 4:00 P.M. It used up those sacks on the first three batches. The dough for the fourth and fifth batches used the new flour. The fourth batch, which was begun at 7:00 P.M. and removed at midnight, was overbaked. This pattern, too, is consistent with the new flour being the source of the problem.

On the basis of these three chronologies, we can conclude with high confidence that the new flour is very likely the cause of the over-baking. Tests of the flour are needed to confirm this finding.

What did you think the problem was? Very few people consider the flour to be the culprit. Most believe that sabotage is probably behind the overbaking, and for two reasons: there is plenty of evidence for sabotage, and most people don’t know how to use a matrix or a chronology to analyze a problem.

There are endless ways of employing a matrix; combining the matrix and chronology techniques is only one. Let’s look at another example of how a matrix can facilitate analysis.

On a sheet of paper create a matrix out of the following information (excerpted from The Universe Within):

37 patients with a particular symptom had a disease.

33 patients with the same symptom did not have the disease.

17 patients without the symptom had the disease.

13 patients without the symptom did not have the disease.

This is good practice in constructing a matrix. Don’t be upset if you have difficulty doing it. The more you use matrices, the easier it will become.

BEFORE CONTINUING, FINISH CONSTRUCTING YOUR MATRIX.

BEFORE CONTINUING, FINISH CONSTRUCTING YOUR MATRIX.

The matrix should appear as shown in Part 1 of the solution to Exercise 14 (page 326).

Creating a matrix is a piece of cake once you get the hang of it. See how putting the numerical data into matrix form has the effect of isolating the data so they can be analyzed more easily, both separately and in combination. See how much easier it is to focus on the data when they are in a matrix than when they are presented in sentences?

The question to which these data are to be applied is the following:

Is there a correlation between the symptom and the disease? In medical terms that means: Do people who display the symptom have the disease?

Based on the data in the matrix, what do you think? Think about it for a moment, then write your answer on a sheet of paper.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE DOWN YOUR ANSWER.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WRITE DOWN YOUR ANSWER.

When a group of nurses was given this problem, 85 percent of them concluded there was a correlation, pointing out that there were more cases with both symptom and disease (37) than in any of the other three categories or that twice as many people had the symptom (37) as didn’t (17). But the nurses were wrong! For even among people without the disease, about the same majority had the symptom (33 had it, 13 didn’t). This becomes clearer when viewed as percentages from the standpoint of symptoms (Part 2 of the solution to Exercise 14). The percentage of those with symptom and with disease is roughly the same as those without symptom and with disease. If the proportion is the same in both cases, there’s no correlation.

Looked at from the standpoint of disease (Part 3 of the solution to Exercise 14), the percentage of those with disease and with symptom was roughly comparable to those without disease and with symptom. Again the numbers are too close: there is no correlation.

Putting the numbers into a matrix allows us to structure the analysis of the data easily and meaningfully. Learn to use a matrix. It’s a marvelous analytic tool.

Let’s do another matrix exercise.

The Hats and Coats Problem

This one is a simple brainteaser and demonstrates graphically how a matrix can help us solve a problem. Here are the clues:

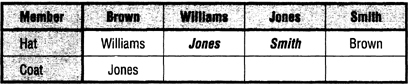

Smith, Brown, Jones, and Williams had dinner together. When they parted, each of them, by mistake, wore the hat belonging to one other member of the party and the coat belonging to yet another member. The man who took Williams’s hat took Jones’s coat. Smith took Brown’s hat. The hat taken by Jones belonged to the owner of the coat taken by Williams.

Who took Smith’s coat?

Let’s work the problem together. We begin by constructing a matrix (Figure 8-6). Our objective is to identify the four members represented by the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4. Let’s go through the clues and fill out the matrix as we go.

The man who took Williams’s hat took Jones’s coat. So we enter “Williams” in “Hat 1” and “Jones” in “Coat 1” (Figure 8-7). We don’t know yet who Member No. 1 is, but we do know it is neither Williams nor Jones, because neither could take his own hat or coat. So we place their names at the tops of columns 2 and 3 (Figure 8-8).

FIGURE 8-6

FIGURE 8-7

FIGURE 8-8

Smith took Brown’s hat. So, Smith, too, cannot be at the top of column 1. Ergo (Figure 8-9), Smith is atop column 4, and Brown is atop column 1. And, of course, Brown goes into “Hat” under “Smith.” Since Jones cannot take his own hat, the only hat left for him is Smith’s, so (Figure 8-10) Smith goes into “Hat” under “Jones.” Ergo, Jones goes into “Hat” under “Williams.”

The hat taken by Jones belonged to the owner of the coat taken by Williams. The matrix shows that the hat taken by Jones was Smith’s. So we have the answer (Figure 8-11): the coat taken by Williams was Smith’s.

Wasn’t that easy? Could you have done that in your head? I certainly couldn’t, and doing it with a matrix is quick and simple.

Just for the fun of it, let’s fill in the other two squares. The only coats left for Smith to have taken are Brown’s and Williams’s, but Smith took Brown’s hat, so he had to take another member’s coat. That means Smith took Williams’s coat. Which leaves Brown’s coat for Jones (Figure 8-12).

FIGURE 8-9

FIGURE 8-10

FIGURE 8-11

FIGURE 8-12

As I said, a matrix is a marvelous analytic structuring tool. Try your hand again at using a matrix on a different problem.

If you were a TV weatherperson, which one of the following circumstances would be best from the standpoint of your reputation among viewers as a forecaster? For a normal midweek workday:

You predict it will snow, and it snows.

You predict it will snow, and it snows.

You predict it will snow, but it doesn’t snow.

You predict it will snow, but it doesn’t snow.

You predict it will not snow, but it does.

You predict it will not snow, but it does.

You predict it will not snow, and it doesn’t.

You predict it will not snow, and it doesn’t.

Construct a matrix to represent this problem, but don’t analyze it! Just construct the matrix.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT THE MATRIX.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT THE MATRIX.

The solution to Exercise 15 (page 327) shows the matrix you should have constructed. See how nicely the matrix organizes (structures) analysis of the problem? There are four possible outcomes—four cells where the predictions and outcomes intersect. The matrix facilitates our thinking by stripping away the superfluous language that surrounded the key words “snow” and “not snow” in the four sentences. The matrix also juxtaposes these key words in a way that enables us to isolate their connections in the cells and to perceive more easily and clearly the distinctions among them. We will return to this problem later in another analytic context.

Your personal services budget for next year is currently under review by your organization’s leadership. You have requested additional funds with which to enlarge your staff. But funds are tight; you may not be granted an increase. Indeed, your budget could be cut. Complicating matters is your recent request to move your staff to a larger building because your present office space is crowded. Tomorrow at a meeting with management you will defend your request for a larger staff. To prepare your defense, you are holding a meeting today with your five assistants to review the arguments, pro and con, for a larger staff. Construct a matrix that relates the three possible outcomes for your personal services budget to the possibilities of moving to a larger building or remaining in your current offices.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT THE MATRIX.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT THE MATRIX.

The solution to Exercise 16 (page 327) shows one way of representing this situation in a matrix. Such a matrix, displayed on a screen as a slide or transparency for all of your assistants to see, would facilitate discussion of the six possible scenarios (alternative outcomes) to ensure that the pros and cons of each were analyzed separately, systematically, and sufficiently.

The more you use a matrix in your analysis, the easier it is. I’m so accustomed to using matrices that the first thing I do, when confronted with a problem, is to ask myself how I can represent the problem in a matrix. And I find that, when I can portray it in a matrix, the problem immediately opens itself to analysis, like the petals of a flower opening up to reveal its inner parts. Moreover, displaying a matrix like this one on a screen to guide discussion at a meeting can be extremely helpful.

For good measure, let’s do one more matrix problem.

You are to attend a personnel meeting that will consider three candidates for promotion to three supervisory positions. Construct a matrix that relates the three candidates to the three positions.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT THE MATRIX.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT THE MATRIX.

The solution to Exercise 17 (page 327) is my version of the matrix. Here again the matrix technique facilitates analysis of the nine possible options. By providing a visual means of focusing our mind on each option, one at a time, the matrix enables us to easily compare and rank the employees by their qualifications for each position.

* The bakery described in this problem is entirely fictitious. For illustrative purposes, liberties have been taken with bakery processes.