BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT ONE MATRIX FOR EACH PERSPECTIVE.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT ONE MATRIX FOR EACH PERSPECTIVE.Thus far we have performed utility analysis on problems that involved multiple options and multiple outcomes but only a single perspective. It is frequently advisable, even necessary, however, to assess utilities from the vantage of more than one perspective. A planning conference can serve as an example for illustrating how utility analysis copes with multiple perspectives.

The administrative staff of a nationwide hotel chain is selecting a site for the annual winter planning conference of its top managers. The choice of site depends on the recreational activities in which attendees can engage. Three sites are being considered: New York City (theaters and restaurants), Palm Beach, Florida (swimming and sunbathing), and Stowe, Vermont (skiing). The administrative staff has just been informed that the top managers attending the conference will be accompanied by their spouses and children. As a result, the staff, in selecting the site, must now take into account the recreational preferences—recreational utilities—of three different groups of people: attendees, spouses, and children. In other words, the staff must view the problem of site selection from three different perspectives.

Utility analysis handles multiple perspectives quite easily by analyzing each perspective separately (constructing a utility matrix for each) and then merging the results to rank the options. Because the options being weighed are the same for each, the matrices are identical in structure. Ensuring this uniformity of structure is critical to the process. Each matrix contains the same options and outcomes, and the probabilities of the outcomes are identical. Only the utility values will vary because each matrix, as I said, views the problem from a distinctly different perspective (identified in the upper left-hand corner) with different self-interests in mind.

In the case of our “Planning Conference” problem, each matrix contains the same three options (New York City, Florida, Vermont). Because weather more than any other factor usually determines whether attendees at a conference are pleased with recreational activities, we will use weather as a class of outcomes and consider two outcomes: “warm-and-sunny” versus “cold-and-rainy.” Construct three utility-analysis matrices, one for each perspective. Do not include a “Rank” column in the matrix. (I’ll explain why momentarily.)

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT ONE MATRIX FOR EACH PERSPECTIVE.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT ONE MATRIX FOR EACH PERSPECTIVE.

Figure 16-1 shows what your three matrices should look like.

The utility analysis process for multiple perspectives is exactly the same as that followed in the preceding chapters: ask the Utility Question for each option-outcome combination, assign utility values, ask the Probability Question, enter the probability values, compute the expected values, add the expected values for each option, and enter the sums in the “Total EV” column.

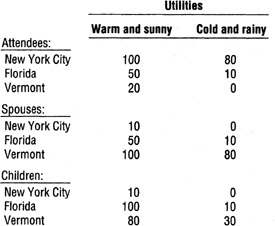

To expedite the exercise, I am furnishing the utility values for each of the matrices (Figure 16-2). The values were obtained by asking the Utility Question for each option-outcome, for example, “If the conference is held in New York City and the weather is warm and sunny, what is the utility from the perspective of the attendees’ enjoyment?” Enter the utilities in the matrices.

FIGURE 16-1

FIGURE 16-2

BEFORE CONTINUING, ENTER THE UTILITY VALUES IN THE MATRICES.

BEFORE CONTINUING, ENTER THE UTILITY VALUES IN THE MATRICES.

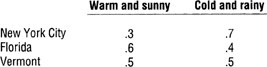

I am also furnishing the weather forecast—the probabilities for the outcomes (Figure 16-3). Enter the probabilities in the matrices and calculate the expected values, add them for each option, and enter the sums in the “Total EV” columns.

BEFORE CONTINUING, ENTER THE PROBABILITIES AND COMPUTE TOTAL EXPECTED VALUES.

BEFORE CONTINUING, ENTER THE PROBABILITIES AND COMPUTE TOTAL EXPECTED VALUES.

Figure 16-4 shows the computations in each matrix.

The next step is to combine the option rankings in the three matrices. We do this by merging the expected values from each of the three matrices in a fourth, appropriately named, merged matrix (Figure 16-5). Construct a duplicate of this merged matrix and enter in each cell the total expected value from the perspective matrices.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT A MERGED MATRIX AND ENTER TOTAL EXPECTED VALUES FROM THE PERSPECTIVE MATRICES.

BEFORE CONTINUING, CONSTRUCT A MERGED MATRIX AND ENTER TOTAL EXPECTED VALUES FROM THE PERSPECTIVE MATRICES.

Figure 16-6 shows the merged matrix with total expected values.

We could, of course, just add the total expected values for each option and accept the one with the greatest expected value as the preferred choice. However, this method of merging preferences would be appropriate only if the administrative staff takes the Laplace approach (meaning it doesn’t have any basis to distinguish differences in the importance of the three perspectives) and values them equally.

FIGURE 16-3

FIGURE 16-4

FIGURE 16-5

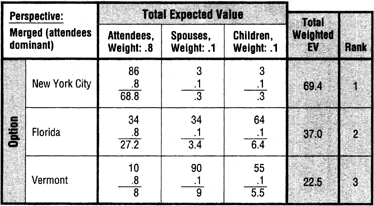

But what if the staff considers the enjoyment of the managers to be many times more important than that of the spouses and children? In that event, we might weight the perspectives as follows: attendees .8, spouses .1, and children .1. Enter these weights at the top of the perspective columns in the merged matrix and add two columns (“Total Weighted EV” and “Rank”) to your merged matrix. Now multiply the total expected values of each perspective by its weight, add the resulting products, enter the sums in a “Total Weighted EV” column, and indicate the final rankings of the options in the “Rank” column.

FIGURE 16-6

BEFORE CONTINUING, ADD “TOTAL WEIGHTED EV” AND “RANK” COLUMNS TO THE MERGED MATRIX, COMPUTE TOTAL WEIGHTED EXPECTED VALUES, AND DETERMINE RANKINGS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, ADD “TOTAL WEIGHTED EV” AND “RANK” COLUMNS TO THE MERGED MATRIX, COMPUTE TOTAL WEIGHTED EXPECTED VALUES, AND DETERMINE RANKINGS.

Figure 16-7 shows what your merged matrix should now look like. With this distribution of weights, New York City is clearly the choice.

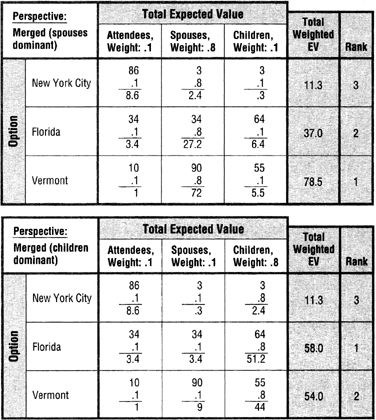

Naturally, different weightings will produce different results. Figure 16-8 shows three sample distributions of weight among the three groups. Figure 16-9 shows how the rankings of the options change when the spouses’ perspective is dominant and when the children’s is dominant.

This technique for utility analysis of multiple perspectives has wide application in problem-solving situations where conflicting interests render a choice among alternative courses of action difficult. Multiple-perspective utility analysis produces decisions that take equitable account of each party’s interests, especially when these parties actively participate in the analysis.

FIGURE 16-7

FIGURE 16-8

FIGURE 16-9

FIGURE 16-10

Step 1: Identify the options and outcomes to be analyzed.

Step 2: Identify and weight the perspectives to be analyzed.

Step 3: Construct an identical utility matrix (Figure 16-10) for each perspective—same options, same outcomes.

Perform Steps 4 through 7 with each matrix.

Step 4: From each matrix’s particular perspective, assign utilities from 0 to 100 to the outcome of each option-outcome combination (each cell of the matrix). There must be at least one 100.

Step 5: Assign a probability to the outcome of each option-outcome combination (each cell).

Step 6: Compute expected values for each option-outcome combination (each cell).

Step 7: Add expected values for each option and enter the totals in the “Total EV” column.

Step 8: Construct a single “merged” matrix (Figure 16-11) with the same options as in the perspective matrices.

Step 9: Enter opposite each option the total expected values for that option from the perspective matrices.

Step 10: Multiply the total expected values under each perspective by the perspective’s weight.

FIGURE 16-11

Step 11: Add the resulting products (weighted expected values) for each option and enter the sums in the “Total Weighted EV” column.

Step 12: Rank the options. The one with the greatest total weighted expected value is the preferred option.

Step 13: Perform a sanity check.

You may wonder why we don’t perform Step 10 (multiplying expected values by each perspective’s weight) before transferring the total expected values from the utility matrices to the merged matrix. Why wait? The answer is that transferring the unweighted values to the merged matrix allows us, first, to view these values side by side, to compare and validate them and, second, to perform a sensitivity analysis more easily by applying different combinations of weights to the criteria as we did in Exercise 45, the “Planning Conference.”

Follow these thirteen steps as you work the two problems that follow.

Ruthless terrorists have hijacked a luxury cruise ship with 1,200 passengers and crew aboard. They have anchored the ship under the central span of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco Bay and claim to have placed more than one ton of plastic explosives in fifty-gallon drums around the decks and below the waterline. They are threatening to blow up the ship—and the bridge with it—unless the following three demands are met:

Payment of $10 million to a bank in a named Third World country

Payment of $10 million to a bank in a named Third World country

Release of five named terrorists imprisoned in the United States

Release of five named terrorists imprisoned in the United States

Unfettered passage out of U.S. territory for the terrorists

Unfettered passage out of U.S. territory for the terrorists

Amnesty from prosecution for the terrorists

Amnesty from prosecution for the terrorists

If these demands are met, the terrorists promise to release the hostages unharmed.

The president of the United States has directed you, his special security adviser, to analyze the situation and recommend which of the following three options for dealing with the crisis will best serve the president’s overall interests:

Acquiescing to all of the terrorists’ demands.

Negotiating with the terrorists for (a) release of the hostages, (b) unfettered passage for the terrorists out of U.S. territory, and (c) amnesty for the terrorists from prosecution but refusing to release the imprisoned terrorists.

Launching a surprise paramilitary assault at night by U.S. Navy SEALs to rescue the hostages and apprehending or, if necessary, killing the terrorists.

The options are to be analyzed against the following classes of outcomes: damage to the ship and the Golden Gate Bridge combined with harm to the passengers and crew. The two factors are combined because the degree of physical damage to the ship and bridge will largely correspond in equal measure to the harm sustained by the hostages; that is, the more damage to the ship and bridge, the more harm to the passengers and crew. Engineers estimate that detonation of one ton of explosives aboard the ship would destroy the ship as well as the bridge’s central span.

The probabilities of the outcomes are the same for both perspectives (Figure 16-12).

You are to analyze the problem applying utility analysis from two perspectives, weighted as follows:

The president’s public approval rating in the United States (.7)

Congressional funding of the president’s highly touted antiterrorism program, which will be the centerpiece of the president’s forthcoming reelection campaign (.3)

FIGURE 16-12

Assign utilities as you see fit.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM USING MULTIPLE-PERSPECTIVE UTILITY ANALYSIS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM USING MULTIPLE-PERSPECTIVE UTILITY ANALYSIS.

The solution to Exercise 46 (pages 340-42) presents my analysis of the problem. My analysis indicates that the paramilitary assault option is strongly preferred. Change the utilities, probabilities, and weights (such sensitivity analysis provides valuable practice in this and other structuring techniques—and it’s fun) and see which changes most affect the ranking of the options. In this way we learn a great deal about the internal workings of a problem.

With only two weeks left in the regular season and critical games coming up that will decide which of several teams will enter the playoffs, contract negotiations between owners and players in the National Basketball Association have reached a stalemate. The players’ union is deliberating whether to strike to force the owners to retreat from their insistence on a 20 percent reduction in the salary cap. The players’ decision on whether to strike rests on two major factors with weights indicated in parentheses:

What effect striking or not striking would have on the salary cap (.6). The owners appear determined to lower the cap to offset reduced revenue from television and ticket sales.

What effect striking or not striking would have on the working relationship between the players’ union and the owners (A).

In past years players have benefitted from the union’s cordial, mutually respectful, productive working relationship with the owners. The players are therefore concerned that a strike may impact adversely on this relationship with undesirable consequences in the near and longer term. More specifically, the players fear that, if the union comes across as too conciliatory, the otherwise balanced power in the relationship could shift to the owners. On the other hand, if the union appears uncompromising and overly demanding, the owners, in reaction, could become more adamant and unyielding in their positions and again jeopardize the equilibrium.

The players’ union foresees three possible outcomes: the owners’ threatened 20 percent reduction in the salary cap, a compromise JO percent reduction, and no reduction. The union anticipates that if the players strike, there is a .7 probability of a 20 percent reduction, .3 probability of 10 percent, and 0 probability of no reduction. If the players do not strike, there is a .8 probability of 20 percent, .1 probability of 10 percent, and .1 probability of no reduction.

Using multiple-perspective utility analysis—and assigning your own interpretations of the utility values—analyze the players’ decision from two viewpoints (the players’ monetary interests and the working relationship between the owners and the union) and determine whether or not the players should strike.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM USING MULTIPLE-PERSPECTIVE UTILITY ANALYSIS.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM USING MULTIPLE-PERSPECTIVE UTILITY ANALYSIS.

Addressing the players’ monetary interests perspective (see Solution to Exercise 47, Part 1, page 342), I first assigned utilities. I gave Strike-20%, the worst option-outcome combination, a utility of 0, because the players suffer the greatest monetary loss from unearned income while no games were being played and from future income because of the 20 percent reduction in the salary cap. Strike—10% received a utility of 50 because the lost future income was halved. Strike-None received an 80 because, though the cap was not reduced, the players lost money while games were not being played. Don’t strike-20% got 50 because, although the cap was reduced 20 percent, the players lost no income during the remainder of the regular season and the playoffs. Don’t strike-10% got 70 because the reduction in the cap was cut in half. Don’t strike-None got 100; that’s the best option-outcome combination. I then entered the given probabilities, computed the expected values, and entered the sums in the “Total EV” column.

I then repeated these steps in the matrix addressing the perspective of the owners’ and union’s working relationship (see Solution to Exercise 47, Part 2, page 343).

I gave Strike-20% zero utility because the outcome humiliated the union and shifted power overwhelmingly in the owners’ favor; this was one of two worst option-outcome combinations. Strike-10% got 90 because the owners were forced to compromise, while the union showed courage and decisiveness in standing its ground; this was largely a win-win situation. Strike-None got 50 because, although there was no reduction in the salary cap, the owners were forced to back down, thereby losing face, which will come back to haunt future owner-union negotiations. Don’t strike-20% (the other worst combination) got zero utility because the owners cowed the union, making the latter appear weak and ineffective, thereby enhancing the owners’ sense of power and compelling the union to be more aggressive in the future. Both of these effects will work against a harmonious relationship. Don’t strike-10% got 20 because it was only slightly better than Don’t strike-20%. Don’t strike-None, the best combination, received a utility of 100. I then entered the probabilities, computed expected values, and entered the totals in the last column.

I next constructed a merged matrix and entered the total expected values from the two perspective matrices, multiplied these values by the weights of the perspectives, added the weighted values, entered the totals in the “Total Weighted EV” column, and determined the ranking of the two options (see Solution to Exercise 47, Part 3, page 343).

This analysis indicates that the players’ union should not strike.

In the utility exercises thus far, no problem has involved more than one class of outcomes. Restricting the exercises to a single outcome class was, of course, intentional, as I have striven to reduce the complexity of the problems to facilitate your learning the utility analysis structuring technique. But problems involving a single class of outcomes are rare, probably limited to crises in which there is a single overriding issue such as whether one remains employed, gets married, or dies. In such crucial situations a single outcome class dominates all other factors.

In most problems there is a bevy of outcome classes that we consider when choosing among alternative courses of action. Let’s look at three examples (Figure 16-13). You will note that, in problems involving multiple classes of outcomes, each class equates to a different perspective. For example, examining the medical risks of having an abortion is the same as examining the problem from the perspective of medical risks.

Let us examine the fourteen steps for handling multiple classes of outcomes in utility analysis.

Step 1: Identify the options to be analyzed.

Step 2: Identify the outcome classes and each one’s range of outcomes and weight each class according to its importance.

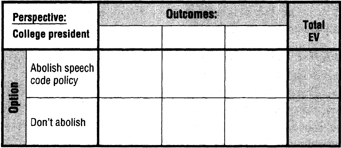

Step 3: Identify the perspective of the analysis.

Step 4: Construct for each class of outcomes a utility matrix (Figure 16-14) with identical perspective and options.

Perform Steps 5 through 8 with each matrix.

Step 5: Assign utilities from 0 to 100 to the outcome of each option-outcome combination (each cell of the matrix). There must be at least one 100.

FIGURE 16-13

FIGURE 16-14

Step 6: Assign a probability to the outcome of each option-outcome combination (each cell).

Step 7: Compute expected values.

Step 8: Add expected values for each option and enter the totals in the “Total EV” column.

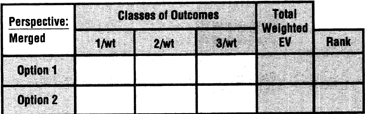

Step 9: Construct a single “merged” matrix (Figure 16-15) with the same options as in the classes-of-outcomes matrices.

Step 10: Enter opposite each option the total expected values for that option from the classes-of-outcomes matrices.

Step 11: Multiply the total expected values under each class of outcomes by the class’s weight.

Step 12: Add the resulting products (weighted expected values) for each option and enter the sums in the “Total Weighted EV” column.

FIGURE 16-15

Step 13: Rank the options. The one with the greatest total weighted expected value is the preferred option.

Step 14: Perform a sanity check.

One can, of course, take multiple-outcome analysis one step further by analyzing each class of outcomes from multiple perspectives, but I strongly recommend against it. Combining multiple-outcome and multiple-perspective analysis would spin the analytic web much too fine. Doing so is akin to studying subtleties—lesser factors and lesser issues. One can analyze them, but, as I said in my earlier discussion of major factors, incorporating subtleties into our analysis is a waste of time because they never play a significant role.

These steps treat classes of outcomes like perspectives. That being the case, what do we enter as the perspective in the upper left-hand corner of each matrix in Step 2? Enter whoever or whatever is the “owner” of the problem—the person or entity that weights the outcome classes and that must ultimately choose among the options. The perspective must be the same for each utility matrix.

Apply these fourteen steps in the exercises that follow.

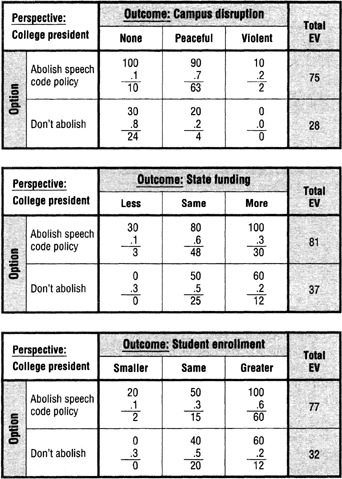

You are the president of a state-funded college and are strongly opposed to the college’s current policy of disciplining students and faculty for insensitive speech. In the wake of several controversial, widely publicized incidents in which both students and faculty members at the college were disciplined for insensitive speech, you are considering whether to abolish or continue the college’s speech code. You are mainly concerned about three things:

Whether your decision will prompt public demonstrations and other disruptions of campus activities (2).

Three outcomes: no disruptions, peaceful disruptions, and violent disruptions. The probability for each outcome, if the code is abolished, is .1, .7, and .2, respectively. The probability, if the code is continued, is .8, .2, and 0, respectively.

How the state legislature will react to the decision; that is, how state funding (which covers two-thirds of the college’s annual budget) might be affected (.5).

Three outcomes: fewer funds, same funds, more funds. The probability for each outcome, if the code is abolished is .1, .6, and .3; if continued, .3, .5, and .2.

How the decision will affect student enrollment (.3).

Three outcomes: smaller enrollment, same enrollment, greater enrollment. If the code is abolished, the probabilities are .1, .3, and .6; if continued, .3, .5, and .2.

Using utility analysis with multiple classes of outcomes, analyze the problem and determine which option is preferable. Assign utility values as you see fit.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM.

I analyzed the problem as follows. In Step 1, I identified three classes of outcomes (campus disruption, state funding, and student enrollment) and weighted them .2, .5, and .3, respectively. In Step 2, I constructed an identical utility matrix for each outcome class (Figure 16-16), identifying the perspective in each matrix as the college president and listing the two options. I then performed Steps 3 through 6 with each matrix (Figure 16-17), assigning utilities and probabilities, computing expected values, and entering the totals in the “Total EV” columns. In Steps 7 through 11, I constructed a merged matrix (Figure 16-18), entered the total expected values from the three classes-of-outcomes matrices, multiplied these values by their respective class weights, entered the products in the “Total Weighted EV” column, and determined from the ranking that abolishing the campus speech code was the strongly favored option. In Step 14, I asked myself whether the results made sense intuitively, which I deemed they did.

FIGURE 16-16

FIGURE 16-17

FIGURE 16-18

You are a midlevel industrial manager who has just been offered an executive position in San Francisco with a significant increase in salary and related perquisites. The problem is that you reside in a small town in Indiana and commute daily to your present job in Indianapolis. The move to San Francisco will uproot your family. Your spouse is a Ph.D. biologist with a full-time career position in a pathology laboratory five miles from your home. Your two teenage children are in the ninth and tenth grades and fully engaged in high school academics, sports, and leadership activities. They have lived their entire lives in this one town and this one home. Your spouse, who has misgivings about forfeiting hard-won opportunities for advancement in the pathology lab, has agreed nonetheless to move to San Francisco if that’s what you want, the two of you having faithfully supported each other’s professional ambitions throughout your marriage of eighteen years.

You determine that your decision to accept or not accept the job offer rests on three factors (three classes of outcomes) which you have weighted with their importance:

Career advancement potential of the new job (.4). There are three outcomes: worse than, same as, better than the potential of your current position.

Potential for your spouse’s career advancement in San Francisco (.3). There are three outcomes: worse than, same as, better than the potential of your spouses current position.

Your children’s intellectual and social development through high school activities that enhance their academic standing, self-assurance, leadership skills, physical fitness, and overall maturity (.3). There are three outcomes: worse than, same as, better than the development possible where you now live.

You estimate that, if you move to San Francisco, the probabilities of your career potential will be 0 worse, 0 same, and 1.0 better; if you stay in Indiana, the probabilities will be .1 worse, .8 same, .1 better. Whether you move or not, the probabilities of your spouses career potential and the children’s development will be .1 worse, .8 same, and .1 better.

Using utility analysis with multiple classes of outcomes, analyze the problem and determine which of the two options —accepting the San Francisco job or rejecting it—is preferable. Assign utility values as you see fit.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM.

My analysis of the problem, presented in the solution to Exercise 49 (page 344), indicates that declining the job offer in San Francisco is the preferred option.

For our final multiple-classes-of-outcomes problem, let us revisit the Algona pollution case, which we looked at earlier when addressing problem restatements.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has discovered volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in effluents from a processing plant of the Algona Fertilizer Company (AFC) in Algona, Iowa. These toxic waste products bypass the city of Algona but are carried into the East Fork Des Moines River, a tributary that feeds into Saylorville Lake, the principal source of water for Des Moines, a city of more than 300,000 people. The Des Moines city council, through the news media and political channels, is putting enormous public pressure on state and federal environmental agencies to shut down the Algona plant. Environmental action groups, with full media coverage, demonstrated yesterday in front of the Iowa governor’s mansion demanding immediate closure of the plant. Local TV news and talk shows are beginning to focus on the issue. AFC’s executive board has hired you, a private research consultant, to analyze the following three options that the Board is considering:

Capturing the toxic runoff in holding ponds for transport by truck and rail to nearby federally approved toxic waste dumps.

This would cost $50,000 per month and is only a short-term solution, because these federal dumps are for emergency, not continuing, use.

Installing state-of-the-art chemical scrubbing and purifying equipment in the plant to remove the toxic waste before it enters the drainage system.

This would cost $3 million and take eighteen months.

Redesigning the plant’s chemical process to eliminate the VOCs.

This involves basic R&D, would cost many millions, and might take years to accomplish. The executive board was recently briefed by a German firm on new experimental technology that totally eliminates the toxic by-products. The technology has been undergoing tests for the past three years in a plant similar to AFC’s, but the German firm has so far not released any test results.

Closing the plant or keeping it running without any changes in its operation are not options.

The board wants you to rank the options from best to worst based on the following major factors (outcome classes):

The degree to which the company’s plan to deal with the problem will eliminate the VOCs from the plant’s effluents (.5).

There are three outcomes to be considered: none of the VOCs are removed, they are partially removed, they are totally removed. No matter which option is implemented, the probabilities of these outcomes are 0 none, .1 partial, .9 total.

How the company’s plan will affect next week’s vote in the state legislature on a bill that would grant significant tax benefits to the state’s fertilizer industry (.3).

There are three outcomes to be considered: the legislation is killed, it is passed with reduced tax benefits, it is passed with full tax benefits.

The probabilities with the transport option are .6 killed, .3 reduced, .1 full. With the scrub—.1 killed, .4 reduced, .5 full. With the redesign—.1 killed, .2 reduced, .7 full.

The cost to AFC of dealing with the toxic effluents (.2).

There is only one outcome considered. Its probability with every option is 1.0.

Using utility analysis with multiple classes of outcomes, analyze the problem and determine which of the three options is preferable. Assign utility values as you see fit.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM.

BEFORE CONTINUING, WORK THE PROBLEM.

My analysis, presented in the solution to Exercise 50 (pages 345-46), indicates that AFC should install state-of-the-art chemical scrubbing and purifying equipment in the plant to remove the toxic waste before it enters the drainage system.