If ever there was a devil’s cauldron for organized crime in the history of old New York City, it was a place known as the Five Points.

Adjacent to a stinking, urban swamp known both as the Collect Pond and Fresh Water Pond, the Five Points became synonymous with evil: a back alley where the poor, sailors, Irish immigrants, freed slaves, and those of a criminal mind-set coalesced around an old structure known as Coulter’s Brewery. The brewery was a squalid structure that housed hundreds of men, women, and children of all ages. Wooden buildings sprouted up nearby and housed thousands more poor souls. The murderous and larcenous bent of these inhabitants earned the place the sobriquets of “murderers’ alley” and “den of thieves.” At the time, it was touted as the closest thing to hell on earth.

“This is the place: these narrow ways diverging to the right and left, and reeking every where with dirt and filth,” was how English novelist Charles Dickens described the neighborhood in 1842 after a visit to the city.

Frontiersman Davy Crockett, no shrinking violet when it came to tough situations, once toured the area, and after seeing more drunk men and women then he had ever experienced in his travels, remarked, “I would rather rique [sic] myself in an Indian fight than venture among these creatures after night . . . these are worse than savages, they are too mean to swab hell’s kitchen.”

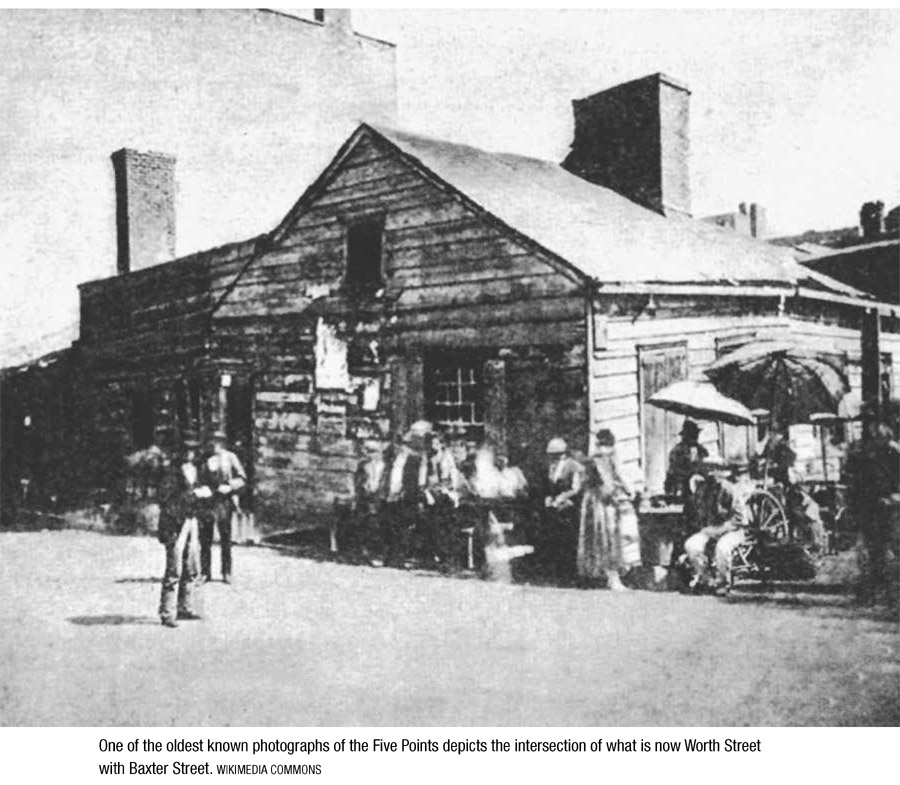

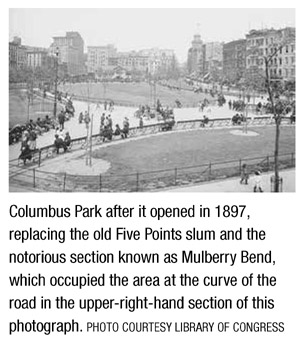

The neighborhood took its name from the intersection of three streets—Anthony, Cross, Orange, and the contiguity of Little Water—located roughly a quarter-mile northeast of City Hall. But don’t look to find all of those names today. Anthony is now known as Worth Street, Cross is Mosco Street, and Orange turned into Baxter Street. Only Baxter and Worth intersect today. Mosco Street no longer goes to the intersection, because it is truncated by Columbus Park. Little Water Street disappeared from city maps altogether. Mulberry Street, although not at that precise intersection, was also considered part of the Five Points, and still exists today as a thoroughfare through Little Italy and Chinatown. Though it once surrounded a place known ironically as Paradise Square, the Five Points remained squalid and an incubator for New York’s criminal life for many years.

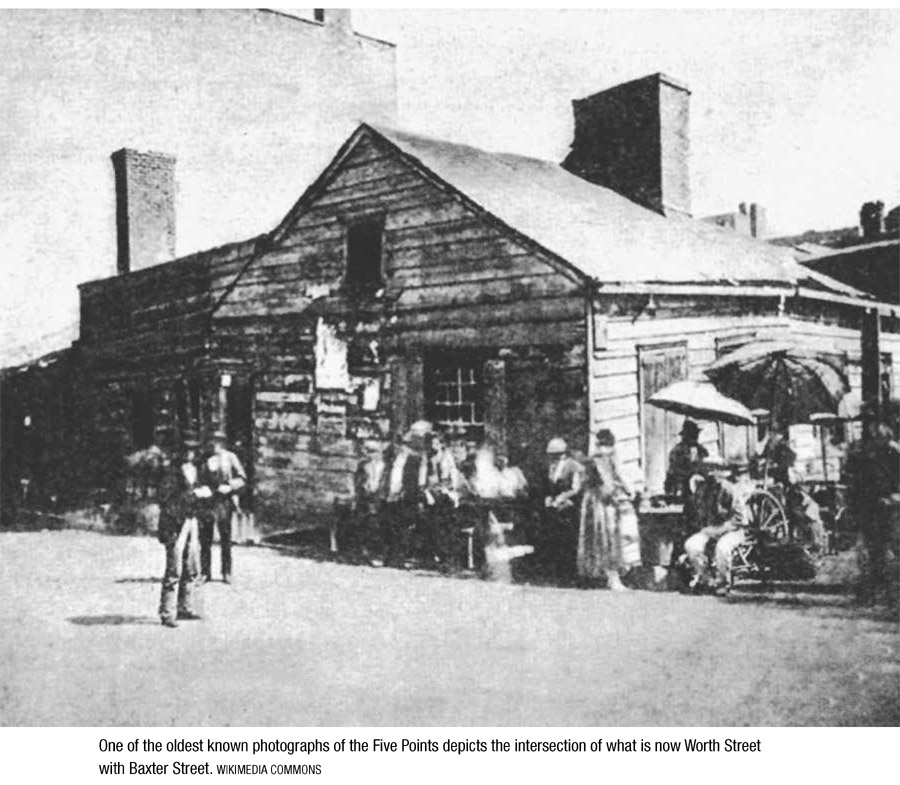

Things were not always so bad in the Five Points. Before it turned into a large outdoor sewer, the Collect Pond (the name is said to derive from the Dutch word kolch, or kalch, meaning a small body of water) was a place for picnicking. The pond’s water was used to make tea. Prior to the Dutch and English settling the area in earnest, the pond was used by local Indians, and heaps of old oyster shells on the west bank were monuments to their presence. The one macabre element was that African slaves were said to have been executed on a spot of land known as Magazine Island, located in the midst of the water at a spot occupied today by Pearl Street and Centre Street. A half-block to the west is the old Negro Burial Ground, now known as the African Burial Ground National Monument, and signifying what is left of the place where slaves were buried in eighteenth-century Manhattan.

Fed by underground springs, the Collect was deep enough for small boats. The pond attracted a brewery, tanneries, and slaughterhouses. But all of that commerce and the large population led to pollution. By 1811, the city finally filled in the pond with earth and debris from a hill that stood approximately to the northeast. Still, despite the disappearance of the Collect, the awful living conditions in the neighborhood led to three outbreaks of cholera.

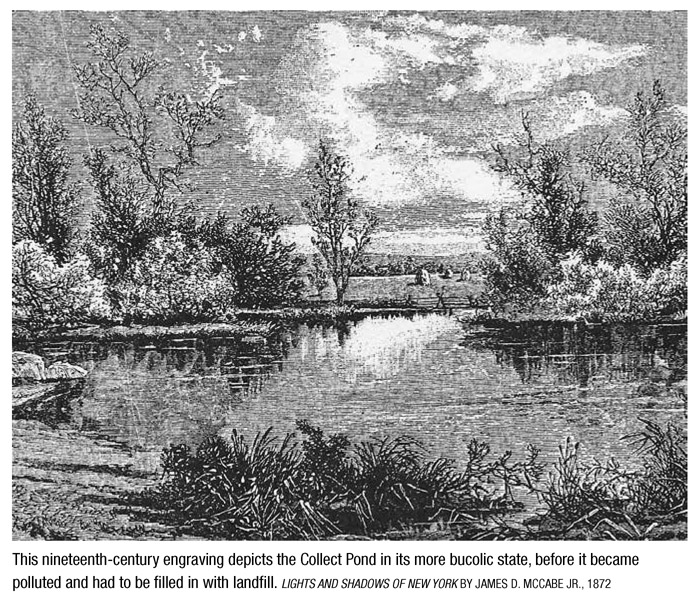

The saloons, which sprouted like mushrooms in the Five Points, attracted hordes of drunks from near and far. Charity workers visiting tenements to care for children would sometimes find all the adults in an apartment lying in a drunken stupor on the floor. Prostitution was also rampant. Some of the streets housed a brothel in almost every building. “Every house was a filthy brothel, the resort of persons of every sex, age, color and nationality,” one historian wrote in 1849. The sex business also led to a particular kind of larceny in which a prostitute would make so much noise servicing her client that the man didn’t notice a wall panel open, allowing thieves to pick the pocket of his coat or pants, which had been left on a chair near the wall. This particular brothel was known as a “panel house.”

Women, it turned out, did more than work in bordellos or ply drinks in the Five Points; they also nurtured some of the city’s early gang culture. Rosanna Peers, who ran a grocery store noted for its rotting and barely palatable vegetables, also had a speakeasy at the intersection of what are known today as Worth and Centre Streets. More than a century later, newspaper columnist Walter Winchell dubbed Peers as the first owner of a speakeasy in the city. Known for its potent cheap liquor, Peers’s establishment became a place where local gangsters, pick-pockets, and thieves congregated, much like the social clubs of the Mafia a century later. Eventually, the criminals coalesced into the Forty Thieves, believed to be the first organized gang in the city’s history. The leader was one Edward Coleman, and children who aspired to be pickpockets (or worse) were organized into an affiliated group known, not surprisingly, as the Little Forty Thieves.

∎ ∎ ∎

Coleman may have been more like the Dickensian character Fagan than a gang leader. It wasn’t long before other criminal groups had willing recruits from the desperate residents of the Five Points and its environs, notably the Bowery area located just to the northeast. Theaters, beer halls, and concert halls took root along the Bowery, and for a time it drew a respectable clientele. But after a while the quality of the entertainment dropped off, and the Bowery became its own haven for gangs. Like the Five Points gangs, the Bowery mobs were sometimes made up of ethnic Irish. But ethnic solidarity—or in this case, the lack of it—didn’t stop them from warring, and the fights between the Bowery Boys and the Dead Rabbits were legendary. Fighting broke out constantly in the Five Points, along the Bowery, or in an area just north of Grand Street.

Among the battlers for the Dead Rabbits was another gangster woman known as Hell-Cat Maggie. Stories from the time she was active, around 1840, distinguished Maggie as a ferocious fighter who had filed her teeth to points and wore claw-like nails on her hands. This made Maggie a double threat in hand-to-hand combat, as she could slash with her hands and do serious damage with her mouth.

Leaping into a street fight, Maggie was known to shriek a battle cry before she would “rush biting and clawing into the midst of opposing gangsters; even the most stout-hearted blanched and fled,” said author Herbert Asbury. Maggie was an Irish immigrant of about twenty years old who fought alongside the Dead Rabbits as they did battle with the anti-Irish Bowery Boys. She would be portrayed in brutal fashion in Scorsese’s 2002 movie version of Asbury’s book by actress Cara Seymour. Maggie was only rivaled in reputation by another woman named Sadie Farrell, known as Sadie the Goat, who earned her moniker because her forte in street fighting was to butt her head against her opponent.

∎ ∎ ∎

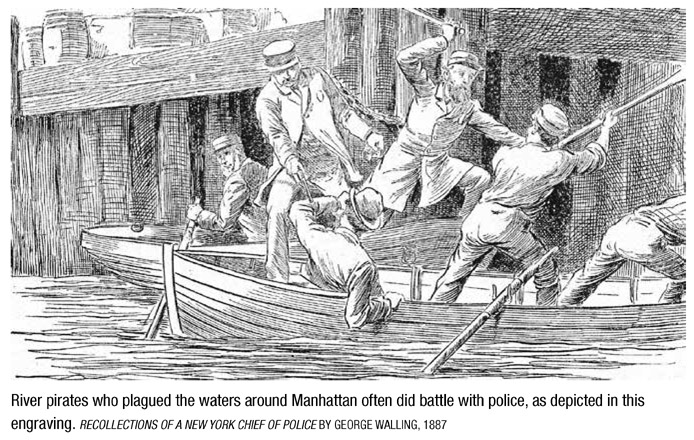

New York City was one of the largest maritime ports in the nation, and thus a target for pirates, who seemed to strike with abandon up and down the docks of Manhattan Island. One of the New York gangs that took to raiding vessels was called the Daybreak Boys, led by Nicholas Howlett and William Saul. The enterprising pair had their men strike before sunrise—hence the gang’s name—reportedly raking in as much as $200,000 in booty from the vessels they targeted, a princely sum in those days.

The police of the time were unprepared to deal with this waterfront thievery and crime, readily admitting to Manhattan newspaper reporters that there was little they could do to stop the thieves. The wharves were too numerous and the opportunities for pillaging too plentiful for the police to do anything to stop the brash and ingenious pirates.

“They are like wharf rats, as much at home in the water as on shore,” was how the Brooklyn Daily Eagle once described the pirates. “When they have committed a robbery or a murder, if too closely chased, they are prepared to jump overboard, dive under a pier, and thus escape arrest or even detection, as has often been done.”

The Daybreak Boys’ penchant for violence is what led to the undoing of Howlett and Saul. It happened during a raid on the sloop Thomas Watson while it was anchored off Oliver Street on the East River (a street now cut off from the river by a housing development). When the gang shot and killed night watchman Charles Baxter with a bullet through his neck, the gunfire alerted police, who cornered the gang at the nearby Slaughterhouse Inn. After a three-hour standoff, both Howlett and Saul surrendered.

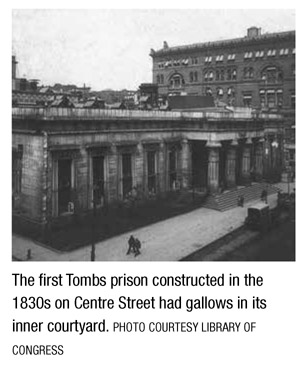

After a trial, Howlett and Saul were convicted of Baxter’s murder, while a third gang member, William Johnson, cooperated with police. The sentence for Howlett and Saul was death, possibly the first instance of capital punishment meted out against a gang leader in New York City history. Their execution was slated for the Tombs, a city prison that had been built—rather unwisely—on the site of the old Collect Pond. The shifting ground under the prison would eventually lead to its demolition, but that was years in the future. The jail had a pair of gallows, and occupied the block on Centre Street, between Leonard and Franklin Streets.

Howlett and Saul were executed on January 28, 1853, and the event was a spectacle. News reporters were given amazing access to the prison, with The Times chronicling in minute detail how they slept soundly the night before and refreshed themselves in the morning with cold water from the “Croton pipes,” the new aqueduct that had been built to bring water into Manhattan. Howlett ate what was described as a “sumptuous breakfast,” while a depressed Saul had no appetite. Before the noon hour of the execution, both men met briefly and shook hands with friends like William Poole and pugilist Tom Hyer, who will be mentioned in greater detail later in this chapter.

Once on the gallows it was Saul who appeared the most contrite and resigned to his fate, praying and then taking a moment to tell friends “to live in the fear of God.” Howlett asked for some chewing tobacco and also prayed. “Oh God, have mercy! Oh God, protect my poor mother,” exclaimed Saul as the hangman put the noose around his neck. A deputy warden who had become close to both condemned men cried as the end neared.

Both men died quickly as they dropped, although observers said Saul’s arms and legs convulsed for a few moments. The crowd, which had filled the courtyard of the Tombs, dispersed and the remains were turned over to grieving friends of the dead and placed in polished mahogany coffins, which had plates engraved with their names, date of death, and ages: Howlett was nineteen years old; Saul, twenty.

∎ ∎ ∎

Sadie “The Goat” Farrell fared better in piracy than Saul and Howlett. While head-butting gave her a reputation, Farrell needed something more substantial to make a living. Eventually, Sadie started a gang of river pirates from Charlton Street who for years plagued the Hudson River. Her crew commandeered a sloop and for months sailed north up the Hudson and raided farmhouses and stately homes, sometimes taking hostages for ransom. Eventually, the local populace got wise and took up arms, making Sadie’s kind of piracy too risky. She eventually returned to her old haunts in Manhattan, making peace with her old rival, a woman known as Gallus Mag, who bit her ear off in a fight.

Gallus Mag was not a woman to trifle with. One newspaper account of 1872 reported that she had been arrested for brawling with a police officer who was investigating a bar fight in a dance house she ran at 338 Water Street. The name Gallus is said to have come from the suspenders she wore, known as “galluses” back in the day. Sadie is said to have been given her ear back, which she wore in a locket around her neck for the rest of her life. After fading away, Sadie’s life and exploits became fodder for twentieth-century novelists.

However, Gallus Mag, otherwise known as Mag (Margaret) Perry, persists in the city’s memory through the old Hole-in-the-Wall saloon she frequented. The site of the saloon, 279 Water Street, is now known as the Bridge Café, near the current site of the South Street Seaport. During the heyday of river piracy the saloon was a hangout for the Daybreak Gang. The popular Bridge Café, about two blocks from the East River, was damaged during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, but survived and is being refurbished, its aging clapboard siding a reminder of its vintage. It is reputed to be the oldest saloon in New York City.

∎ ∎ ∎

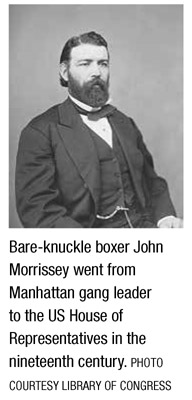

Gambling, politics, and gangs worked well together in the mid-nineteenth century in Manhattan. Gambling parlors were all over the area around City Hall, and some of the establishments were top-shelf, complete with servants, food, and musicians at the ready to entertain clientele. With nicely appointed furniture and fixtures, the places resembled the best-run brothels, which weren’t very far away. A man eager to make his mark and earn a good wage could look to the gambling halls for a job. Such was the case with John Morrissey, an Irishman from upstate Troy who excelled at using his fists as a bare-knuckle fighter.

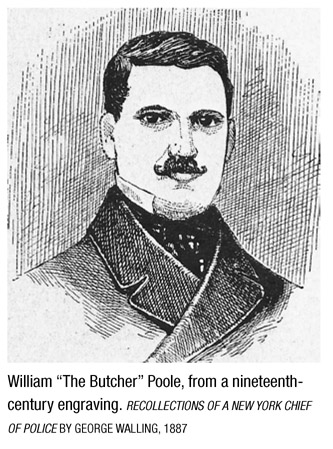

The problem for Morrissey was that he decided early in his career to run up against two other street fighters who were just as good as he was: Tom Hyer and William Poole. Hyer, a heavyweight boxing champion, and Poole, butcher by trade from Christopher Street, were among the special group of gangsters who had said farewell at the gallows in January 1853 when Saul and Howlett were hanged for the murder of the watchman aboard the vessel Thomas Watson. Poole and Hyer were two gang leaders closely allied politically to the Know-Nothing Party, a deep-seated national movement that counted among its adherents former president Millard Fillmore, who became the party standard-bearer in the 1856 presidential race, but lost.

During the election of 1854 in New York, Poole and his gang of toughs put out the word that they were going to intimidate voters, a threat that some citizens took seriously, forcing them to form their own group to protect polling places. Morrissey joined the citizen poll watchers and amassed sufficient numbers to intimidate Poole and his toughs, who backed off from their raids on polling stations. Morrissey allied himself with Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party organization that had taken up the cause of the new Irish immigrants as a way of gaining new voters.

Know-Nothings like Poole and Hyer didn’t like immigrants, particularly Catholics, Irish, and Germans who were seen as poor and living in slums like the Five Points. Morrissey, being Irish and Catholic, had two strikes against him in Poole’s eyes. The Election Day standoff in 1854 didn’t help matters. The men became mortal enemies.

Morrissey and Poole were such bitter foes that they couldn’t stay in the same room without a fight breaking out. In fact, Morrissey attempted to shoot Poole at Stanwix Hall, 579 Broadway, but his handgun misfired three times. Poole was getting ready to attack the befuddled Morrissey with a knife when cops arrived and placed them both under arrest, although nothing came of it.

But in the world of New York gangs, arrests weren’t much of a deterrent. Morrissey and Poole had just been released from police custody when, on a February night in 1855, they both returned to Stanwix Hall, which at the time was a major entertainment complex with gambling and restaurants in lower Manhattan. To start things off, a couple of Morrissey’s street-fighting friends, Jim Turner and Lew Baker, picked a fight with Poole at the bar. The situation reached a flash point when one of Baker’s friends, Patrick McLaughlin, spat in Poole’s face. Turner pulled a pistol but was such a bad shot that he wound up wounding himself in the arm with his first bullet. Turner managed to squeeze off another shot and succeeded in wounding Poole in the leg. Baker then weighed in and shot Poole twice—once in the stomach, and another time in the chest, near the heart. A still-feisty Poole managed to throw a knife at a fleeing Baker, but was a bit shaky and missed his mark.

At first Poole was taken to his home on Christopher Street and expected to recover. But his condition worsened. On March 8, 1855, about two weeks after he was shot, Poole died at his home at 164 Christopher Street. Cemetery records show that he was thirty-three years and eight months old. Legend has it that his final words from his deathbed were “Good-bye, boys, I die a true American.” Poole’s funeral was so large that it was described as having “almost regal pomp.” He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery (see chapter 14). Baker tried to flee the city on a brig headed for the Canary Islands, off the coast of Africa, but a nativist friend of Poole’s, financier George Law, loaned his speedy yacht, the Grapeshot, to law enforcement officials for a transatlantic chase. The Grapeshot overhauled the vessel carrying the fleeing Baker, who was returned to New York. There, he was charged, along with Morrissey, Turner, and McLaughlin, in connection with Poole’s death. But in three trials jurors couldn’t agree on a verdict, and the case was dropped.

∎ ∎ ∎

William Poole was part of a breed of early New York gangsters who made themselves powerful by using their muscle to help their political agendas. Similar groups, like the American Guards and True Blue Americans (who happened to be Irish), also seemed political. However, many of the other gangs existed to protect their turf and were named for their style of dress: Shirt Tails wore their shirts untucked from their pants; Plug Uglies had enormous plug hats with high crowns; the Roach Guards had blue-striped pants; the Dead Rabbits, considered by some historians to be an affiliate of the Roach Guards, wore red stripes and entered battle with a dead rabbit on a pike.

Fighting seemed to be the sport of gangs, and large-scale battles in and around the Five Points became legendary, with some volunteer firefighting companies also getting involved. The men who fought weren’t just dissolute criminals. Often tradesmen after a day’s work would put on their gang clothing and feel like they were a part of something much bigger than their small daily lives. Herbert Asbury in The Gangs of New York said some estimated these groups had over 30,000 members. Street brawls often involved up to a thousand combatants, and would leave scores bloodied.

Politics sometimes played a part in the bigger brawls. Just before the 1856 mayoral elections, the Dead Rabbits clashed with the Bowery Boys, a nativist group from the Bowery that attacked Five Points polling places. At first the Bowery group gained the upper hand, but the Dead Rabbits pulled reinforcements into the area armed with pistols, knives, and other weapons. The fighting went on for hours, and eventually the Dead Rabbits prevailed, beating back the Bowery Boys and in the process assuring victory for Mayor Fernando Wood, who was a favorite of the Irish.

But many of the street gangs, while organized in some fashion, weren’t moneymaking operations. Their reasons for existing seemed more rooted in territory and the sense of self-esteem that membership provided. Other groups had a more economic imperative, and in that respect were more of the forerunners of the Mafia, which is rooted in making money. One such group was the Whyos, which grew to prominence around the Five Points in the years after the Civil War. The gang was, as Asbury described it, “as vicious a collection of thugs, murderers, and thieves as ever operated in the metropolis.” It appears to have been the first Mafia-like collective of crooks and murderers. Legend had it that the Whyos acquired their name from the peculiar call uttered when they were going to a fight.

What made the Whyos different than the other gangs was the way the members organized themselves to carry out burglaries, bank robberies, and street thefts, notably pickpocketing. Operating from Baxter Street and the area around the Transfiguration Church on Mott Street, the Whyos became the preeminent gang in the 1880s and ’90s. The gang had its fair share of fights, and because many of the members were armed, gunfights were constant. In one case, the Whyos got into a drunken gunfight at a saloon on the Bowery appropriately named The Morgue. It was reported that all the combatants were so inebriated they couldn’t shoot straight, and nobody was hurt.

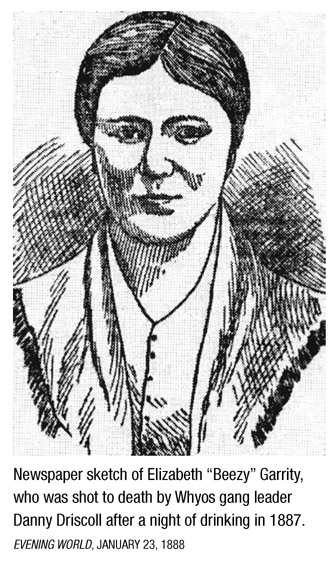

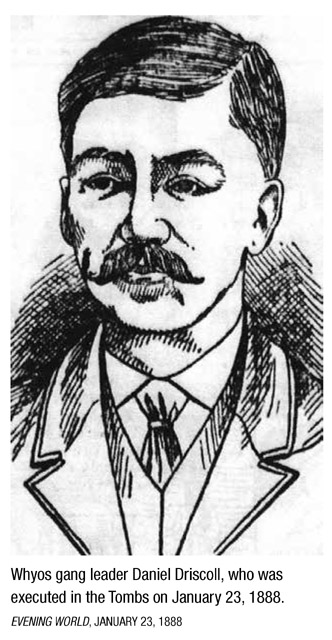

But it was cases of both reckless and deliberate shooting that ultimately led to the undoing of two men billed as the greatest leaders of the Whyos: Daniel Driscoll and Danny Lyons. One night in 1887, Driscoll and another man got into a fight after a night of drinking. As it turned out, a sixteen-year-old young woman named Elizabeth “Beezy” Garrity, described in the newspapers as “a dark-eyed, well formed girl,” had developed a fascination with Driscoll, and took to hanging out with him. It was on this fateful night that Driscoll, Garrity, and some others were getting drunk in Chatham Square, and decided at 3:50 a.m. to visit a “disreputable lodging house” at 163 Hester Street. The lodging-house owner, who had fought with Driscoll in the past, tried to close the door to keep him out. But the Whyos leader drew his revolver and recklessly fired through the door, mortally wounding Garrity, who was already inside. The autopsy found she had been shot in the stomach, and noted that Garrity was a “remarkably beautiful woman.” After a widely publicized trial, Driscoll was sentenced to be hanged in the Tombs.

Execution days were traditionally public spectacles in New York City during this era, and on “Hanging Day,” the church bells would ring when the condemned was finally swinging from the gallows at the Tombs. The newspapers, renowned for their cutthroat competitiveness in chasing a story, increased the public fervor surrounding these events. In the case of Driscoll, his hanging was something the Evening World newspaper covered feverishly, and in the age before smartphones, set up an elaborate Rube Goldberg–style signaling system so that the journalist could quickly get the story out on the street the moment Driscoll was dangling from the rope. A reporter in the courtyard of the Tombs would energetically wave a handkerchief the instant Driscoll’s body plummeted off the gallows so that another staffer of the newspaper—stationed on the roof of a Leonard Street building adjacent to the Tombs—knew that the prisoner had been executed. The man on the rooftop then waved a red flag, visible to an associate at the top of the Colwell Lead Company tower, two blocks south at what is now the intersection of Centre Street and Foley Square.

The man at the top of the tower then faced south and waved a similar flag. At Printing House Square, where the newspaper was printed, an employee of the Evening World sat waiting on an office windowsill with binoculars. Once he had spotted the flag being waved at the tower, the newspaper employee alerted his colleagues, who started the presses rolling with the story that Driscoll was dead. The Evening World bragged that it scooped the competition by five minutes in getting the papers on the street.

Danny Lyons’s demise came about eight months later in rather ignominious fashion. A street tough with a head shaped like a bullet and what was described as a “lantern jaw,” Lyons had done a couple of years at Sing Sing Prison, and had only recently been freed on bail after assaulting a policeman. After taking over the leadership of the Whyos gang following Driscoll’s execution, Lyons became a regular at a saloon run by Daniel Murphy at 199 Worth Street, just due west of the Five Points, and an address no longer in existence. One August day in 1887 the twenty-eight-year-old Lyons was already three sheets to the wind from a day of drinking when he demanded that barman Walter Butler continue to serve him. Butler refused, and Lyons had a tantrum and started throwing bottles around. Murphy caught one of the bottles between the eyes and finally had enough, telling Lyons, “Come on, you have to go out.”

The pugnacious Lyons reached for his pistol, but Murphy already had his own gun drawn and fired at the gang leader, striking him in the side of his head, over the right ear. Murphy promptly turned himself in to the police—a smart move, because other Whyo members who learned of the shooting wanted to take a piece out of his hide. Murphy claimed self-defense, and even gave cops the gun Lyons had drawn. Meanwhile, Lyons was taken to the local Chambers Street Hospital, where surgeons tried in vain to prevent his death by lifting some pieces of his skull to relieve the pressure on his swollen brain.

There was no report that Murphy was ever indicted for the shooting, and business at the saloon in the days after the Lyons shooting picked up. Years later, there was some confusion about Lyons’s fate, principally with Asbury’s account in The Gangs of New York, where he claimed that the Whyos leader was executed on August 21, 1888, in the Tombs, for the murder of beloved athlete Joseph Quinn. But other news accounts note that the Daniel Lyons who was executed had no relation to the Whyos leader.

∎ ∎ ∎

The deaths of Lyons and Driscoll didn’t signal the end of the Whyos, but at the close of the nineteenth century, the geographic center of the Mob—indeed, any gang that frequented the Five Points area—was shrinking. There had been some changes over the years, as charities like the Five Points Mission, which took over the site of the Old Brewery, and the Five Points House of Industry worked to improve the situation facing residents—particularly the children. But the dilapidated and dingy houses, the narrow alleyways and filth-lined gutters, did nothing to improve the reputation of the neighborhood.

Writer James D. McCabe Jr. described the locale in Lights and Shadows of New York Life: “[T]he sidewalk is almost gone in many places and the street is full of holes. Some of the buildings are of brick . . . others are one- and two-story wooden shanties. All are hideously dirty.” On a tour, McCabe found that every dwelling seemed to have a home distillery that produced “the vilest and most poisonous compounds” as whiskey, gin, rum, or brandy. Brothels seemed to be almost as plentiful. The city spent a small fortune regularly disinfecting the area known as “Mulberry Bend,” the part of Mulberry Street at the intersection with Baxter Street that was slightly angled, as it is to this day.

Something had to change, and by 1895, the city had finally approved a plan to tear down the Five Points.

In June 1895 the city began auctioning off the dilapidated buildings of the Five Points so that demolition could begin to create a park. The structures, made infamous over the years as hotbeds of gang activity, were sold for as little as $1.50. The winning bidders won the right to tear down the buildings and sell the debris for scrap. They also had the right to obtain back rent from many of the displaced tenants who were months in arrears, and spent their time scurrying around to find new lodgings.

Demolition of the Five Points buildings on Baxter Street, Mulberry Bend, and surrounding areas began by June 8, 1895. The park to occupy the new space was designed by Calvert Vaux, who had co-designed Central Park years earlier. The approximately three-acre parkland, said to be one of New York’s first urban parks, was finally opened in the summer of 1897, and was graced with curved walkways, trees, and flowers. Summer concerts gave a nod to the ethnic succession seen in the old Five Points, with a choice of music ranging from Italian operas and Irish folk tunes to standards like “My Old Kentucky Home” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”