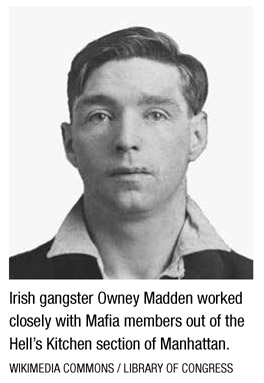

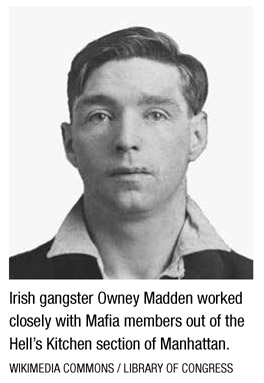

While the names of Mafia leaders like Gallo, Gambino, and Lucchese became household names, there were other major gangsters who would also become powerful, if not as widely known. Among them were the leaders of the Irish Mob who for decades worked out of the West Side of Manhattan in a neighborhood that became known as Hell’s Kitchen. The Irish had always played a role in the major gangs in the city going back to the time when the Five Points neighborhood was the training ground for criminals. Crime historians say it was Owen “The Killer” Madden who made Hell’s Kitchen a place where gangsters could thrive, and where they forged a link with the Italian Mob.

After Madden retired to Arkansas in the 1930s, Hell’s Kitchen remained a stronghold of Irish crime. For years the man considered boss of the Irish Mob was a bookmaker and gambler named Hugh Mulligan, who while little known to investigators was a major force in the underworld. Bookmakers were a dime a dozen in the city, but what made Mulligan special was his reputation as a conduit for bribes to police officers, a skill that earned him the label of “classic fixer” from law enforcement. Mulligan, a portly man with a fleshy face, would be convicted in 1971 for criminal contempt during a grand jury investigation into police corruption, linked to his gambling, loan-sharking, and other rackets. Hit with a three-year prison term, Mulligan died in July 1973 from natural causes.

Mulligan’s protégé was Mickey Spillane, a handsome, dark-haired Irishman who started earning his arrest record at the age of sixteen, and was once shot by a police officer while robbing a Manhattan movie theater. Spillane married into the politically connected McManus family of the West Side, and for the rest of his life earned a reputation as a dyed-in-the-wool tough guy who, when he was indicted in 1970 for refusing to answer questions from a grand jury, took a jail sentence instead of talking.

Spillane held court at the White House Bar, 637 Tenth Avenue. It was from this location that Spillane reportedly took a piece of the action from a number of gambling dens on Tenth Avenue. Because of his political connections through the McManus family, Spillane became something of a dispenser of jobs and advice to the Irish community.

But Spillane’s gentlemanly ways weren’t to last. A number of younger aspiring Irish men vied for power in Hell’s Kitchen. Among them was James Coonan. In his seminal book about the Irish Mob in New York, The Westies: Inside New York’s Irish Mob, author T. J. English traced Coonan’s descent from a middle-class upbringing to a life as a hardened killer. Although his parents held stable jobs, Coonan began running with neighborhood toughs in Hell’s Kitchen. The rest was history as Coonan became a fierce rival to Spillane, killing some of his trusted lieutenants.

Coonan cemented his status as a key organized-crime power on the West Side when he and his trusted lieutenant Mickey Featherstone sat down with Gambino crime-family boss Paul Castellano (Carlo Gambino had died in 1976) and agreed to do business with the Italians. Spillane had kept the Mafia at arm’s length, refusing to allow the Italians to get the job for the construction of the Jacob Javits Convention Center. But Coonan agreed during his meeting with Castellano at Tommaso’s Restaurant in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, to have his crew of Irish killers serve as hired hit men for the Gambino borgata. What distinguished Coonan and his small band of Irish gangsters was the way they would dismember their victims. They weren’t satisfied with just killing someone; they had to take the extra step of cutting the victim to pieces. In one case, the Westie put the head of his victim in a freezer until they could decide on a better way to dispose of it.

After the Gambino alliance, Coonan was full of himself. His recklessness extended to the way he lied to Castellano about the murder of Mafia loan shark Charles “Ruby” Stein. In the Mob, Stein was known as one of the most prolific loansharks on the street, with loans out totaling over a million dollars. As recounted by English in The Westies, Coonan used his 596 Club, a bar at 596 Tenth Avenue, as an execution center. In May 1977, Stein was lured to the club where he was shot dead and dismembered, something described in detail in English’s other book about Irish criminals, Paddy Whacked: The Untold Story of The Irish American Gangster. (The term “paddy whack” is urban slang for a beating.) Stein’s body parts later washed up on a beach in Queens. Spillane was shot dead outside his home in Woodside, Queens, a few days after Stein was killed.

∎ ∎ ∎

As strange as it might sound from a racial point of view, the Mob had been a part of life in Harlem for years. In fact, it was Irish gangster Owney “The Killer” Madden who set up one of the early nightclubs in the black community, the Cotton Club, when it was at the northeast corner of 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue. According to author Ron Chepesiuk, the location was first known as the Douglas Casino, complete with a vaudeville theater, dance hall, and banquet room. The casino never really took off, and, according to Chepesiuk, reopened as a supper club where the person out front was former heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson. The Cotton Club opened in 1923, and Madden spared no expense, giving the club a “log cabin exterior and a ‘jungle décor’,” Chepesiuk writes in his book, Gangsters of Harlem.

“While the Cotton Club was in the heart of Harlem, a neighborhood that was becoming overwhelmingly black, it had a ‘whites only’ policy, although light-complexioned blacks were sometimes able to gain admission,” notes Chepesiuk. However, the chorus line included some of the prettiest black women around, and the shows and music were spectacular. During Prohibition, clubs run by the Mob popped up all along 133rd Street to cater to crowds looking for booze and excitement.

Beset by legal problems, ex-con Madden eventually had to leave New York City, and he “retired” to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1933. The Mob continued to assert itself in Harlem life, pushing the sale of marijuana and controlling nightclubs. As the years went by, blacks continued in the numbers racket that became the province of some memorable characters. One of them was Stephanie “Queenie” St. Clair, whose brashness and moxie became legendary. Along with her enforcer, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, St. Clair resisted the efforts of Mafia-connected gangsters like Dutch Schultz of the Bronx to squeeze her out of the business.

Eventually, the scope of the numbers business in Harlem attracted more white gangsters like Schultz, who quickly supplanted some—but not all—black operators. After Schultz was assassinated by the Mafia in 1935, other Italian gangsters came in and organized numbers operations of their own, vying with the black operators for control. St. Clair would be remembered, according to the stories that surfaced later, for sending Schultz a message as he lay mortally wounded in the hospital: “As ye sow, so shall ye reap.”

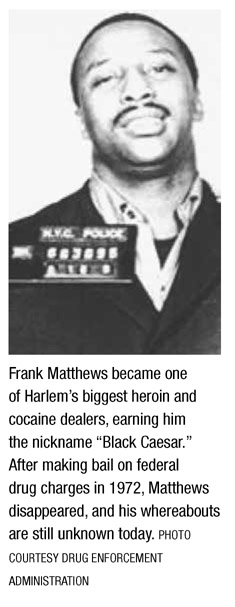

But it was in narcotics that black gangsters would make their mark, ultimately breaking away from Mafia control of the heroin trade and forming their own organizations. Among the most prominent was Frank Matthews, who by the early 1970s was believed to be one of Harlem’s biggest dealers of heroin and cocaine, a distinction which earned him the sobriquet “Black Caesar.” It was Matthews, Chepesiuk notes, who hit upon the idea of getting all of the black and Hispanic dealers to work together to streamline the drug trade and figure out how to deal with the Mafia. However, Matthews’s run as Harlem’s top drug lord and leader of what became known as the “Black Mafia” quickly unraveled with his arrest in September 1972, on federal drug charges. Matthews made bail and disappeared a year later, with his whereabouts unknown to this day.

Others were quick to fill the void left by Matthews. Among the major drug lords was Leroy “Nicky” Barnes, a strapping man who was a product of the streets of Harlem. Barnes started as a low-level drug dealer, and after a few years in prison came out and built a narcotics empire. Prison wasn’t a bad thing for Barnes, as he was able to forge friendships and business alliances there with a number of mafiosi, notably Joey Gallo and Matthew Madonna. Gallo taught Barnes the value of organizing the Harlem drug trade, and Madonna, court records and news accounts stated, worked out arrangements where he supplied heroin to the Barnes organization.

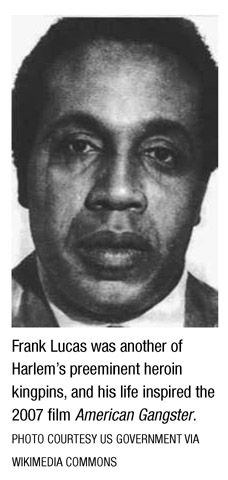

Another Harlem drug lord was Frank Lucas, whose claim to fame in the heroin racket rested with the story that he had hit upon the idea of smuggling heroin back into the United States in the coffins of dead soldiers killed in the Vietnam War. There is much doubt about whether or not Lucas ever smuggled narcotics that way, although he insisted he did. But it became clear that Lucas did engage in heroin smuggling, and over the years claimed 116th Street, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, as the place where the junkies could get his product. He also hooked up with Italian suppliers on nearby Pleasant Avenue. Lucas became rich, and dressed in a $50,000 chinchilla coat, flaunting his wealth. But he wound up in prison after federal and state convictions in the 1970s and ’80s, later getting out early after he turned informant. Lucas’s life inspired the 2007 film American Gangster, starring Denzel Washington. “It was worth every nickel of it,” Lucas said in an interview about his past life.

Barnes also became a wealthy man from heroin and lived a flashy lifestyle. He owned so many luxury cars that he could have run a dealership, and he often bankrolled charitable events around Harlem. Barnes’s organization used the Harlem River Motor Garage at 112 West 145th Street as a place to transact many of the drug deals. Barnes, known as “Mr. Untouchable,” conducted himself with a swagger and arrogance that drew the attention and considerable resources of the federal government, and he was indicted in 1977. While some saw the federal case against Barnes as problematic due to the way he insulated himself from drug deals, a jury nevertheless convicted him, and he received a life sentence without parole.

But prison didn’t mark the end for Barnes. Angered by reports that many of his old associates had maneuvered to take over his empire and were allegedly having sex with his wife and girlfriend, Barnes became a cooperating witness for the federal government, and helped to put many of his former associates behind bars. In August 1998 Barnes was released and placed in the witness protection program. Meanwhile, Barnes’s old Mafia contact, Matthew Madonna, after serving a twenty-year sentence for drug trafficking, was freed from prison and became a captain in the Lucchese crime family.