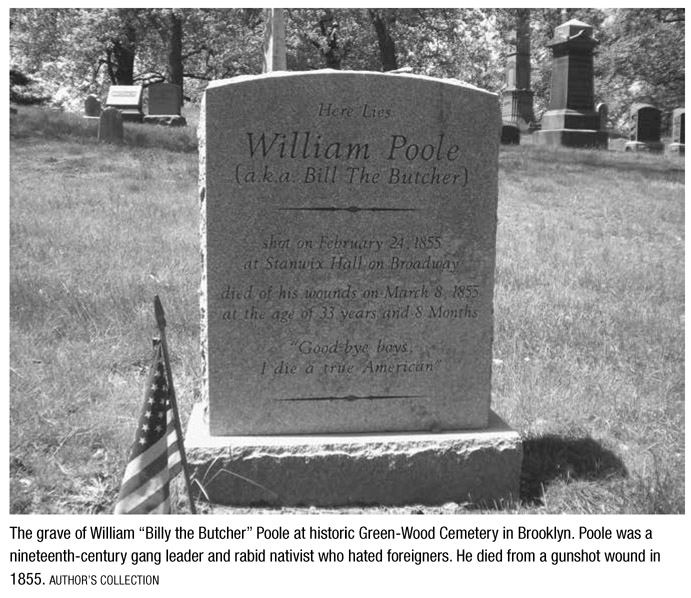

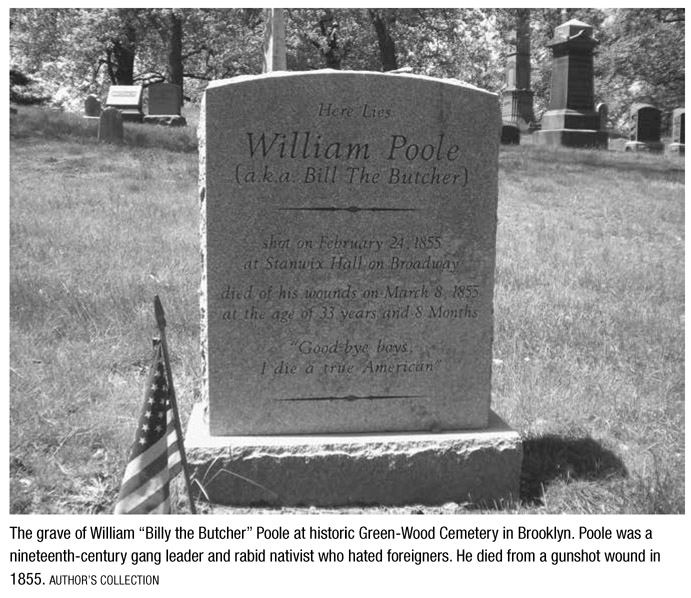

When William “Billy the Butcher” Poole died in 1855 of wounds suffered in a shooting at Stanwix Hall in Manhattan, his funeral became a spectacle of the day. For his burial, Poole’s family and friends chose Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, a place that was fast becoming the cemetery of note for the city. Created in 1838, Green-Wood was styled as a rural cemetery on the most elevated point in Brooklyn, overlooking New York harbor to the west. The cemetery was established after it became clear that there was no longer grave space in Manhattan churchyards, and that the growing city would very quickly need a larger place to accommodate its deceased. With its gently sloping hills, attractive scenery, and glacial terrain, Green-Wood became a place for family outings, as well as funerals. Its main entrance is through a graceful arch at Twenty-Fifth Street and Fifth Avenue.

Poole’s funeral procession began at his home in Manhattan and would travel some six miles to Green-Wood. His coffin was placed on an open hearse pulled by four white horses, which had been parked on Hudson Street. Poole’s corpse was clothed in a dark suit, and a political badge from the Organization of United Americans was stretched across his chest. At the head of the coffin was a large gilt eagle that had been covered with black crepe. The hearse was also decked out in black velvet on each side, bearing Poole’s last words—“I die a true American”—in silver letters.

The procession from Poole’s old neighborhood, Christopher Street, through lower Manhattan to the ferry to Brooklyn, was said to have been witnessed by over a hundred thousand onlookers. The newspapers reported that liquor stores and cigar shops stayed open along the route. In the procession were city aldermen, politicians, gang members, noted criminals, firefighters, and members of various political clubs. Delegations came from Philadelphia and Baltimore. In an attempt to keep things peaceful, funeral organizers barred any group from displaying banners or slogans that might provoke those who had been Poole’s enemies and political opponents. The marchers walked south to the South Ferry in Lower Manhattan, where the hearse was placed on a vessel for the short voyage to Atlantic Street in Brooklyn, which at that point in time was a separate city.

The crowds in Brooklyn were said to have been as large as those which accompanied Poole in Manhattan. Ferries from the Williamsburg section transported thousands more so they could be close to the cortege as it made its way to Green-Wood, under the watchful eyes of scores of police officers. It took about five hours for the procession to make its way from Poole’s home on Christopher Street in Manhattan to the cemetery. Poole’s body was placed in a receiving tomb, and four months later, on July 9, 1855, eventually placed in a grave just off the cemetery road known as Landscape Avenue.

For the longest time Poole’s grave had no headstone, perhaps because his family and friends were worried about the notoriety. But in February 2003, at a time when Martin Scorcese’s film Gangs of New York was playing in theaters, Green-Wood unveiled a three-foot-high headstone at Poole’s grave. In the film, Poole was characterized as William “The Butcher” Cutting, a role played by actor Daniel Day-Lewis. Engraved into the stone were the dates Poole was wounded at Stanwix Hall, and when he died. There are also those famous last words attributed to the venerable tough guy: “Good-bye, boys, I die a true American.” Cemetery president Richard Moylan did the unveiling, noting to the small crowd that Poole, who was immortalized as one of New York’s early gangsters, was being commemorated as a historical figure.

∎ ∎ ∎

Frankie Yale’s livelihood as a Brooklyn gangster in the 1920s was that of a bootlegger, the career of choice for any criminal with aspirations for greatness. Yale was born in southern Italy with the name Francesco Ioele, a surname which over time turned into “Uale” and “Yale.” Once in the United States, Yale gravitated toward a life of crime, and as a teenager was mentored by Johnny Torrio and brought into the Five Points Gang.

Although he was good with his fists and could elicit fear in his world, Yale also became adept at some of the early Mafia business rackets. In the days before electric refrigerators, homeowners and businesses relied on icemen to bring them blocks of ice. It was backbreaking work, and competition could be tough. Yale went into the ice business in Brooklyn and essentially got all of the companies organized into a cartel, which kept prices artificially high. Through strong-arm methods, Yale got many ice sellers to use his company as a source of supply, ensuring an additional flow of income. Yale used the same heavy-handed tactics in the laundry business, where he kept the union out of companies. He also developed a brand of cigars known as “Frankie Yales,” which he forced stores to sell.

As a hedge against the relatively short longevity of his associates, Yale opened up a funeral home at 6604 Fourteenth Avenue in the Dyker Heights section of Brooklyn, just across the street from where he lived with his family, a location that would unwittingly prove to be convenient later on. Eventually, Yale opened up a bar and dance hall in Coney Island that was given the grand name of the “Harvard Inn.” The establishment, which no longer exists, was located on Seaside Walk, a popular thoroughfare not far from the Atlantic Ocean.

It was at this dance hall that another young Italian immigrant named Alphonse Capone, eager to make his way in the criminal world, took a job as a bouncer and bartender. Capone’s reference for the position was Johnny Torrio, mentor to a lot of young toughs.

Capone biographer Laurence Bergreen describes the young gangster’s time at the Harvard Inn: “He made himself a popular figure . . . they liked Al, the jolly way he served up the foamy beer at the bar and occasionally took a turn on the dance floor himself. It was not exalted work, but the job kept him busy and on display.”

Not everyone at the bar took a shine to Capone, however. After he made a rude remark about the derriere of a patron’s sister, Capone got into a fight and was slashed with a knife on the left side of his face, an injury which healed but left him with a disfiguring scar and the moniker “Scarface.”

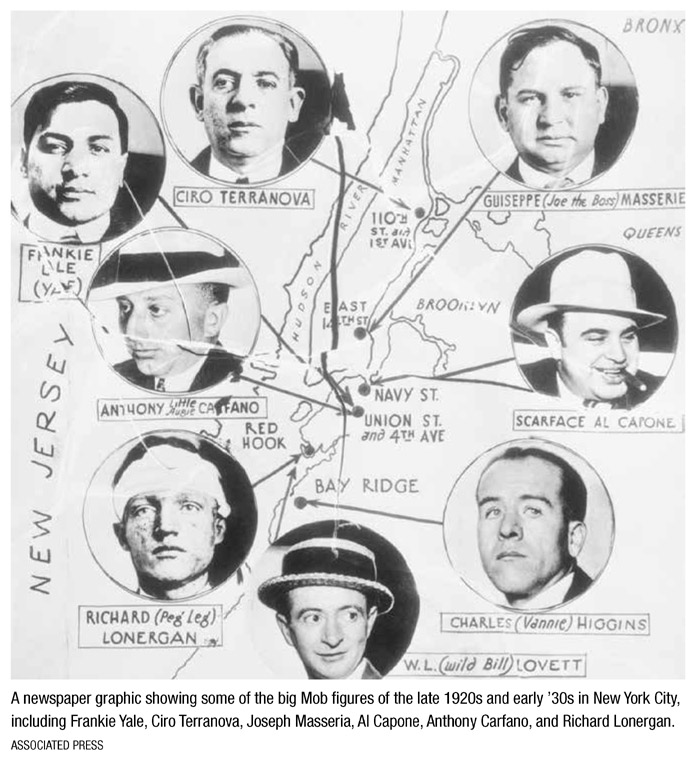

Capone would eventually go to Chicago, where he rose to prominence as a Mob boss in his own right, eventually eclipsing Yale. But back in Brooklyn, Yale and Capone remained allies, and with Prohibition in full swing, they had worked out a deal in which Yale was able to import whiskey and scotch, transporting it by truck to Capone’s speakeasies in Chicago. Yale also was closely tied to a number of the up-and-coming mobsters of the day, notably Joe Adonis and Albert Anastasia. Also a man to be reckoned with was Anthony Carfano, who was known by the strange nickname of “Little Augie Pisano.”

As powerful as Yale was in Brooklyn, he made a lot of enemies on the way up. He even raised Capone’s suspicion that he had been stealing some of the whiskey destined for Chicago. So, as tough as he was, Yale was the object of a number of assassination attempts. The first known effort came in early 1921, when gunmen fired at him as he was about to enter a nightclub in Lower Manhattan. Yale’s bodyguard was killed, and Yale sustained a serious chest wound that kept him in the hospital for months.

Two years later, Yale attended a christening at a local Brooklyn church and decided to walk back to the family home, sending his wife and children ahead with his chauffeur, Frank Forte. Gunmen followed the vehicle, and as Yale’s family and the chauffeur exited, they shot at Forte, apparently mistaking him for his boss.

The assassination attempts didn’t slow Yale down, and in one memorable confrontation, he forced some of his Irish opponents to back off from a fight in a way that led to some long-term benefits for the Italian Mob. On the evening of Christmas Day, 1925, Yale, Capone, and a group of their Italian friends were gathered for drinks at the Adonis Social and Athletic Club at 152 Twentieth Street in Brooklyn. A rival bunch of Irishmen known as the White Hand, led by Richard “Peg Leg” Lonergan—so named because he had a wooden leg—came to the club, demanded drinks, and began insulting the Italians with ethnic slurs like “dago” and “wop.”

The result was predictable: The lights went out at the Adonis and shooting started in the darkness. In the end, three of Lonergan’s men were dead, and the leader was found cowering under a piano. Capone finished off Lonergan with a shot to the head, and his wooden leg, according to Bergreen, was taken as a trophy.

The killing of Lonergan had the effect of breaking the Irish power on the docks of Brooklyn and set up the Italians as the new force on the waterfront. This would eventually become a power base for the likes of Albert Anastasia and his kin. In the meantime, Yale’s position as a top Mob boss in Brooklyn was solidified by the way Lonergan and his group were so decisively dispatched.

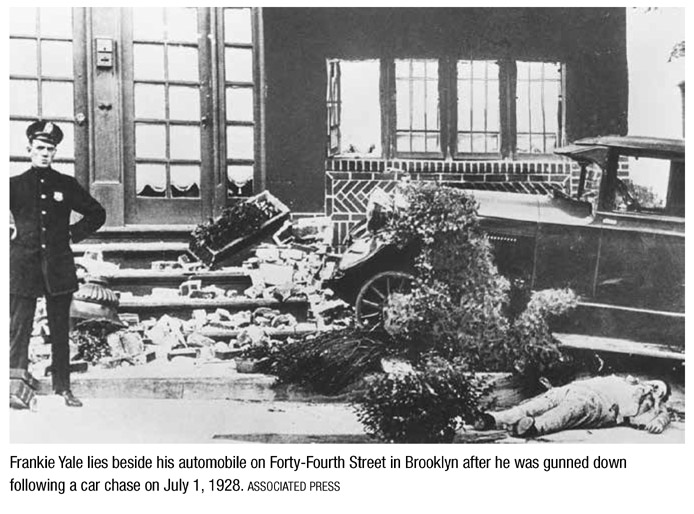

But as is often the case in the Mafia, Yale’s luck ran out—although it took a bit of trickery to make that happen. Although Capone and Yale had forged a tight relationship, the bootlegging business caused things to fray. Capone learned that Yale was hijacking booze meant for Chicago. For Capone, Yale’s duplicity meant that he was effectively stealing from him. On Sunday morning, July 1, 1928, Yale was driving alone in Brooklyn in his new Lincoln, a large car with running boards, the automotive style of the day. The vehicle was bulletproof, and it is likely that Yale felt secure driving without any bodyguards.

According to later police accounts, Yale noticed another vehicle to his rear with four male passengers that looked suspicious. Yale started to take evasive action and turned quickly onto Forty-Fourth Street in the Fort Hamilton Parkway section. Both cars were speeding, and then suddenly, someone in the pursuing vehicle fired a shotgun at Yale and killed him. Yale’s car continued to move down the street and finally came to a stop in the front yard of 923 Forty-Fourth Street, where a bar mitzvah party was going on. The crash took out some shrubbery and small trees in the front section of the yard. The assailants fired a burst from a sub-machine gun into the vehicle and then sped away. When the cops arrived at the bloody scene, they asked Yale, “Who did it?,” but he was already dead.

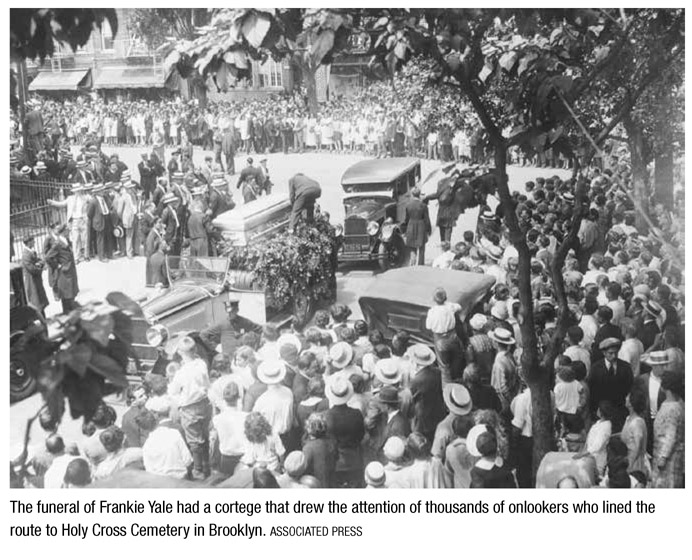

Yale’s funeral took place four days later and was one of the Mob extravaganzas of the day. The silver-colored casket was valued at $15,000. Some estimates put the crowd of mourners that lined the route at up to one hundred thousand, although that seems high even for a Mob boss. There were 35 flower cars and 250 limousines to carry the wiseguys, friends, and family members. At Holy Cross Cemetery—a small pocket burial ground run by the Archdiocese of Brooklyn, in Flatbush—things got even more dramatic, as two women showed up at the grave claiming to be Yale’s wife. One wife was named Mary, and newspaper reports said that Yale was also married to a slim, attractive brunette named Luceida Gullioti, of Manhattan. Ultimately, it was Yale’s wife Mary, the one whom he lived with and had two children, who was given his personal effects at the police station. The items were a testament to Yale’s wealth and style: a belt buckle with seventy-five diamonds, $2,000 in cash, and a diamond ring.

Yale’s grave is in an out-of-the-way section of Holy Cross. The stone is engraved with his original Italian name, “Ioele.” The curious might easily overlook the gravesite, because a low-growing tree has enveloped the headstone, creating a protective canopy of leaves in the spring and summer.

∎ ∎ ∎

Yale’s rackets and bootlegging operation were taken over by Anthony Carfano, another well-known gangster, and Michael Abbatemarco. Carfano would live a long time and graduate into the ranks of the modern Mafia to hobnob with the likes of Vito Genovese, Lucky Luciano, and Frank Costello. But Abbatemarco would barely outlive his old boss, Yale.

A handsome Italian man cut from the same cloth as Yale, Abbatemarco was known in the German-American Brooklyn neighborhood he grew up in as “Michael der Schatz,” which translated to Michael “Sweetheart.” As a gangster he took to flashy clothing and jewelry, spending money like it wouldn’t last. He was in many ways like Yale, including in the way he died.

The end came for Abbatemarco while he was driving alone in his Nash coupe on a Brooklyn street before sunrise on October 6, 1928. A witness said a man came up from the backseat of the coupe and fired at Abbatemarco several times, killing him. The vehicle was stopped by the curb on Eighty-Third Street, between Twenty-Fourth and Stillwell Avenues. The first police officer on the scene looked inside and thought the driver was sleeping at the wheel, until he noticed the blood running down Abbatemarco’s face.

So, three months after Abbatemarco had been at Yale’s funeral, giving him a final send-off, he was back again at Holy Cross Cemetery, this time in his own $6,000 silver-bronzed casket. While the crowd wasn’t as large as it was for Yale, the floral displays were just as ostentatious. Anthony Carfano sent a tower of roses topped by a fluttering dove, and Al Capone provided what was described as an “equally ornate piece.”

Because he was a US Army veteran, Abbatemarco’s service featured a military firing squad from nearby Fort Hamilton, which sent up an appropriate volley. But the real noise came from the women in Abbatemarco’s life. His grieving wife cried, “Don’t leave me, Mike. . . . You are all I have, and I love you.” She fainted, as did Abbatemarco’s mother and his two sisters. Since Abbatemarco’s son had died three years earlier at the age of four in an auto accident, the grave diggers had exhumed the child’s casket and then placed it on top of his father’s before filling in the grave. Finally, a bugler blew “Taps.”

∎ ∎ ∎

Physical deformities weren’t obstacles to the criminal aspirations of New York mobsters. There was Giuseppe Morello, whose congenitally deformed right hand he prominently displayed in mug shots. Another racketeer with a similar infirmity was Giuseppe Piraino, who because of his paralyzed right fingers was known as “The Clutching Hand.” The moniker also was appropriate given Piraino’s habits with money on the street: He didn’t like to part with any of it. Like most mobsters at the time, Piraino was a bootlegger who had a soda bottling plant. Police said it was used as a place where Piraino could cut his grain alcohol and dilute the liquor. Piraino had visions of expanding his territory beyond what others in the Mob would allow, so, on March 27, 1930, Piraino and his competitors were called to attend a Brooklyn conference—a “sit-down,” in modern parlance—about his straying into the territory of others. The talk wasn’t productive, apparently, and Piraino left without agreeing to anything, including parting with some cash.

As Piraino walked toward 151 Sackett Street, he looked jaunty, with a $2,000 diamond stickpin in his tie and a smaller diamond on his ring finger. As he reached the doorway he was shot, with three rounds hitting him in the heart in such a tight pattern that it was later said the holes could have been covered by a half-dollar—although Piraino probably would have preferred a silver dollar for the analogy. Piraino dropped into the gutter, and although there were dozens of people on Sackett Street, nobody saw anyone fire the shots. The lack of witnesses—or at least, those who would say anything—didn’t prevent detectives from arresting a dockworker named Joseph Florino, who had once been imprisoned in Sing Sing. He was awaiting execution for the murder of Piraino before a retrial cleared him.

Funeral pomp had become expected among Brooklyn gangsters, and Piraino’s family paid the price, with a $7,000 casket of metal and a cortege of seventy cars and floral tributes. His burial was at Green-Wood Cemetery, although today there is no listing for Piraino’s interment, suggesting that he may have been placed in the grave of another family member. Piraino’s widow claimed his death was an “accident,” and tried to collect double indemnity under his $5,000 life insurance policy, which would have given her $10,000. The insurance company said Piraino wasn’t an accident victim and stood firm. The case was settled for $8,000, enough to pay for his casket and then some.

As it turned out, Piraino’s widow needed all the money she could get for funeral arrangements. On October 6, 1930, about seven months after Piraino was slain, his son Carmine was gunned down as he walked past 1857 Eighty-Fifth Street in the Bath Beach section. Two gunmen had come out of a driveway and walked up behind Carmine, shooting him in the back of the head and in his chest. The assailants briskly walked into another driveway and disappeared. Police noted that Carmine died on a street within the area of Frankie Yale’s bootlegging distribution ring. There was never an arrest made for the murder.

∎ ∎ ∎

While the Italian mobsters were the major force in Brooklyn crime during the 1930s, the Jews were a potent force in their own right. Throughout a good part of the 1920s and into the ’40s, a cadre of Jewish gangsters known as the “Brownsville Troop” would put many notches on their belts. Their Italian Mob counterparts who used them as hit men, notably Albert Anastasia, also recognized the convenience of their location. Historians may disagree as to how many died at the hands of this Brooklyn clique, but estimates run from scores to hundreds. The activities of the Brownsville Troop and the related Murder Incorporated (the Jewish-Italian combination) are incorporated throughout this book. They are mentioned here for the fact that they used a peculiar candy store at 779 Saratoga Avenue, under the elevated railway in Brownsville, as a base and safe haven.

Although the shop was housed in a nondescript storefront on the first floor of the building, it occupied a special place in New York criminal history. Upstairs was the Hollywood Royal Chinese restaurant, which specialized in chow mein. Rose Gold, the Jewish mother of a hoodlum known as Sam “The Dapper” Siegal, ostensibly ran the establishment. The store’s awning advertised “candy, soda, and cigars.” Gold earned the nickname of “Midnight Rose” because her business stayed open throughout the night, at least for a special breed of men who hung out at the corner of Livonia and Saratoga and populated the ranks of the Brownsville Troop and Murder Inc.

Gold was said to be illiterate and didn’t stay in the store all the time, but the men from the corner knew that they could enter the premises at night and do their business. In one case the candy counter was where a set of keys for a stolen auto were hidden. The car was later used in the murder of George Rudnick, a gang associate who was suspected of being an informant. When Rudnick’s body was found by cops, there was a card in his pocket, allegedly signed by an assistant prosecutor, which thanked him for his help. The card was planted so that news of it would leak out and be a warning to other potential informants about what could happen to them.

Gold was more than just a kindly woman who accommodated her son’s friends with a wink and a nod as they planned their mayhem. She sometimes posted bail when the Murder Inc. members got arrested. In testimony during the Rudnick murder trial, one of the prosecution witnesses, the infamous Jewish gangster Abe Reles, testified that Gold was a partner in his loan-sharking operation. A report prepared for New York governor Herbert Lehman by special prosecutor John Harlan Amen in 1941 noted that Gold handled about $400,000 in loans as part of their shylocking operation.