2. LIVING WITH NOAH

LIKE ANY RESPECTABLE Miami lawyer, Wayne Pathman owns a Ferrari and lives in a big house on the water in the Sunset Islands neighborhood of Miami Beach. The Sunset Islands (there are four), like many of the islands that have arisen in Biscayne Bay, were created by digging up mud and piling it high and then surrounding it with a wall to keep the mud from washing away. Basically, it’s the same thing the Calusa did for thousands of years. Many of the homes on the islands, which are just a few feet above sea level, go for $10 or $15 million and have stunning views of downtown Miami. Pathman lives just down the street from Philip Levine, the wealthy mayor of Miami Beach, and not far from a $25-million Mediterranean Revival mansion that rocker Lenny Kravitz once owned. Pathman, who was in his early fifties at the time of this writing, grew up in Miami Beach and built his career handling land lease and zoning negotiations for Miami businesses and developers. In 2017, he became chairman of the Miami Beach Chamber of Commerce, where he has worked hard to get Miami’s business leaders to understand the risks of sea-level rise and, among other things, stop building developments right on the water. “Noah was right,” he told me at dinner one night. “When you talk about flooding, nobody listens. They all think it’s not their problem. Have you taken a helicopter up and seen the cranes?”

I had not, but it sounded like a good idea to me. A few weeks later, I found myself up in the air with Sheryl Gold, another Miami Beach native and longtime community activist, and Roni Avissar, a former Israeli military pilot who is now a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami. We flew from a small heliport to the west of the city, near the Everglades, then swooped in toward Miami at low altitude. I could see boats cruising across Biscayne Bay, people sunbathing on rooftops. But Pathman was right: from the air, downtown Miami was a forest of cranes. Most of the construction was condo towers. A number of them were designed by rock-star architects like Norman Foster or Zaha Hadid and were architecturally interesting in an early-twenty-first-century postmodern sort of way. But from the helicopter, they all looked the same.

From the air, you could see how the city pushed up against the ocean. And it wasn’t just new condo towers—it was hotels, hospitals, university buildings. They were all right on the shore, dangling their toes in the water.

Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring, a book about the dangers of pesticides that inspired the modern environmental movement, tried to articulate the roots of our desire to live near water. She wrote about how life itself grew out of the sea, and how “each of us began his individual life in a miniature ocean within his mother’s womb, and in the stages of his embryonic development repeats the steps by which his race evolved, from gill-breathing inhabitants of a water world to creatures able to live on land.” Carson foresaw humanity making its way back to the sea, where, if it could not return to the ocean physically, it would “re-enter it mentally and imaginatively.”

From the air, that was precisely what seemed to be happening in Miami.

A few billion years ago, Florida was part of Africa. When the Atlantic Ocean opened up, Florida was left behind, stuck onto the North American continent. It was just a big chunk of rock. Sea levels rose and fell over Earth’s history, covering Florida with hundreds of feet of ocean water for millions of years, then exposing it again. Each time the water was high—and that was a majority of the time—the ocean was full of microscopic creatures that ate and shit and died. Their skeletons and excrement and shells drifted to the bottom, along with bits of coral and grains of sand and mud, most of which washed down from the Appalachian Mountains in the north and onto what is now Florida. Eventually, all this stuff went through a chemical transformation that cemented it together and turned it into limestone. That limestone grew thicker and thicker, an accumulation of excrement and skeletons and coral that is now three thousand feet deep in some places.

During the rise and fall of the seas, the water sometimes paused long enough to allow reefs to form, or to create little pearl-like grains called ooids. One particularly unusual set of conditions arose about 120,000 years ago, when sea levels were about twenty feet higher than they are today. Along the southern coast of Florida, shallow, warm, turbulent waters created what was essentially an ooid factory, where bits of shells and pellets of muddy shrimp excrement and coral could tumble around and acquire a fine coating of carbonate that gave them a pearly luster. When the ooids grew to about the size of large grains of sand, they settled to the bottom. (You can see the same process on certain beaches in the Bahamas today.) Over time, the ooids piled up, and, when sea levels fell again, cemented into ooid limestone. Eventually the ooids themselves weathered away, leaving behind an unusual limestone with holes in it. That pile of porous ooid limestone is now part of what is known as the Atlantic Coastal Ridge, which is roughly thirteen feet above sea level and runs from Palm Beach down to about Homestead. More than five million people live along that ridge today.

Close-up of Miami limestone with dissolved ooids. The dark areas are porous, allowing water to flow through. (Photo courtesy of D. F. McNeill/University of Miami)

In the pancake-flat topography of southern Florida, the emergence of the coastal ridge is a big deal. It prevented water from draining from the flat land to the west of the ridge, turning it into a swamp that became the Everglades. Eventually, a few rivers worked through low spots, allowing some water to flow out of the swamp (the Miami River, which cuts through downtown, is the biggest). Over time, the old reef eroded. Seeds lodged here and there. Hardy trees like pine and mahogany grew, and the ridge became a rocky highway between the swamp and the beach. The Tequesta, a Native American tribe on the east coast of Florida that was related to the Calusa on the west coast, used it for travel, as did panthers and deer and other dry-land-loving creatures of South Florida. And in 1890, it was here on the coastal ridge, right at the mouth of the Miami River, that a forty-one-year-old widow named Julia Tuttle bought a house that was once part of Fort Dallas, a remote military outpost built in the early nineteenth century. Tuttle fixed up the old house and made it a showplace—she was arguably the first person to grasp both the beauty of the landscape and the opportunities to get rich quick in South Florida.

Tuttle’s home is long gone, of course. But there’s a historic marker on the spot. If there is a dead center of today’s Miami, the middle of the crane forest, this is it. On either side, towering condos look out over Biscayne Bay, toward the port and Miami Beach. As I walked along the shore one day, enormous yachts motored up the river, some blaring Drake or Kanye West, festooned with men and women in skimpy bathing suits. I flashed back to pictures I’d seen of Tuttle, “the Mother of Miami,” who first persuaded Henry Flagler, the exceedingly rich cofounder of Standard Oil, to build a railroad down to this godforsaken place. The story of her sending orange blossoms in 1896 to Flagler, who had a house in Palm Beach, and persuade him to extend his railroad from Palm Beach to Miami is the founding myth of the city. And once Flagler’s railroad arrived—well, you know what happened. The twentieth century happened.

Although they didn’t know they were living atop an old coral reef, the locals called the high rocky ridges reefs and the lower sandy, soggy areas glades or sinks. Homesteaders liked the glade because it did not require clearing and the soil was good for raising vegetables—especially winter vegetables that grew to maturity before the summer rains. Once you cleared out the pine and mahogany, the rocky ridges turned out to be good for citrus. The elevation of the ridges also gave protection from the biggest threat settlers faced there: water. In South Florida, that boundary between water and land was always amorphous.

Exhibit A: the memoirs of George Merrick, who was the founder of Coral Gables, a master-planned community south of Miami, where much of the Florida gentry (including former governor Jeb Bush) now lives. In 1901, Merrick was a fifteen-year-old boy living on the family homestead near Miami. The house was up on the coastal ridge, but that didn’t stop the water when torrential rains hit that year. “We were living with Noah,” Merrick later wrote in an account of his life on the homestead. All the land below the coastal ridge flooded. The Merricks’ vegetable garden disappeared under six feet of water. Roads became impassable, and on the low ones, the water was so deep that some wagons floated away.

Inside their “ark,” as Merrick called their house, it was even worse. As the water rose, the family pulled boards off the barn and nailed them to the cabin floor to elevate it above the floodwaters. Armies of roaches and other insects sought refuge inside the house. “The more we killed, the more the roaches seemed to reappear, as if raining from the skies,” Merrick wrote. The frogs invaded too: “There was something horrifying in the clamor that unceasingly enveloped the cabin. The din was as if every rain drop, as ceaselessly they fell, gave birth to a new voice; a new croak, gurgle, gurk, grackle and shriek.” Alligators swam in from the Everglades, bellowing, devouring half-drowned rabbits. Merrick and his father floated wood in from the barn for the cookstove on a makeshift raft. Then the manure pit overflowed, causing Merrick’s father’s feet to break out in wormlike red eruptions, which Merrick’s mother tried to cure by pouring iodine into the open wounds.

Early settlers like the Merricks understood that if civilization was going to continue, something had to be done about the water. More important, these pioneers figured out that draining the Everglades was the equivalent of creating free land. By 1909, dredging of the Miami Canal had begun, and what followed was perhaps the most rapid, most dramatic, most heedless remaking of a landscape that humans had ever attempted. When this massive water-diversion scheme was finished, thousands of acres in the Everglades had been drained dry and opened up to the speculators.

And speculate they did. The taming of the Everglades unleashed a land boom that was unlike anything seen before in America. “From the time the Hebrews went into Egypt, or since the hegira of Mohammed the prophet, what can compare to this?” one newspaper mused. The pilgrims included celebrities like the boxer Gene Tunney, the actor Errol Flynn, and businessmen such as Alfred du Pont, J. C. Penney, and Henry Ford. But ordinary Americans also headed to Florida to get rich, enjoy vacations, or retire in a sunny climate. “The suntan, once a symbol of labor, became a symbol of leisure,” Michael Grunwald writes in The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise.

But even then, there were dissenters. As Grunwald points out, Charles Torrey Simpson, the most eloquent of Florida’s preservationists, suggested a new ethic in which Floridians no longer considered themselves superior to nature and stopped trying to tame it and exploit it:

There is something very distressing in the gradual destruction of the wilds, the destruction of the forests, the draining of the swamps, the transforming of the prairies with their wonderful wealth of bloom and beauty—and in its place the coming of civilized man with all his unsightly constructions, his struggles for power, his vulgarity and pretensions. Soon this vast, lonely, beautiful waste will be reclaimed and tamed; soon it will be furrowed by canals and highways and spanned by steel rails. A busy, toiling people will occupy the places that sheltered a wealth of wildlife.… In place of the cries of wild birds will be heard the whistle of the locomotive and the honk of the automobile. We constantly boast of our marvelous national growth. We shall proudly point someday to the Everglade country and say: Only a few years ago this was a worthless swamp; today it is an empire. But I wonder quite seriously if the world is any better off because we have destroyed the wilds and filled the land with countless human beings.

Geologically speaking, Miami Beach is a new kid in town. Three thousand years ago, around the time the Great Pyramids were being built, the sandbar that we now call Miami Beach began to form on the platform of ooids off the coast. The sand (most of which was ground-up rocks from the fast-eroding Appalachian Mountains) began to collect in the shallow water. Mangrove seeds washed up. Insects arrived. By the late 1800s, it was a dense tangle of mangrove and palmetto, rattlesnakes, rats, mosquitoes, and other insects. “Virgin jungle crept right down to the beach, a jungle as dense, forbidding and impenetrable as only the tropics can produce,” one early visitor wrote. “It was impossible to proceed more than a few feet into its depths without hacking a path with a machete.”

For most of human history, few people thought of beaches as welcoming places. In fact, for early European explorers, the beach had been a place to be avoided. It was a place where you might land your boat, but otherwise it was a treacherous zone that was associated with death and disease and that marked the line between civilization and nature. When the English, Dutch, and French began to settle the New World in the seventeenth century, they weren’t scouting potential beach resorts. They wanted timber, fur, and fish.

In Europe, the first people to occupy the beach and build houses facing the sea were upper-and middle-class landlubbers who were convinced of the therapeutic quality of sea air and water. In the mid-eighteenth century, lured by extravagant promises of miracle cures, English invalids and hypochondriacs began gathering in places like Brighton, on the English Channel. They frolicked in newly invented bathing machines and spent hours beachcombing and sightseeing, activities that were completely alien to the locals, who, as novelist Jane Austen observed, avoided the water except when making a living from it: “Sea views are only for urban folk, who never experience its menace. The true sailor prefers to be landlocked rather than face the ocean.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, people began building houses and hotels closer to the shore. Newly built piers in places like Atlantic City, New Jersey, were essentially extensions of land and carried visitors over rather than onto the beach itself, giving them a safe vantage point from which to look both to sea and back to land. For these early vacationers, the pull of the beach was its very emptiness and “cleanliness”—no shipwrecks, no dead bodies washing up, no sign of dirty industrial life. One French sociologist called this the “aesthetic conquest of the shore by the vacation ideology.”

By the 1870s, Atlantic City was a full-fledged beach resort, and Coney Island had Ferris wheels and luxury hotels. But Miami Beach was still just a tangle of mangroves and mosquitoes. In 1876, the US government built what may have been the first permanent structure on Miami Beach—the Biscayne House of Refuge. Intended for victims of shipwrecks, of which there were many on this treacherous coastline, it was stocked with provisions, clothing, blankets, and first aid equipment. There must have been some romance to the place, however, because records show that the wife of Jack Peacock, keeper of the house, bore children there in 1885 and 1886.

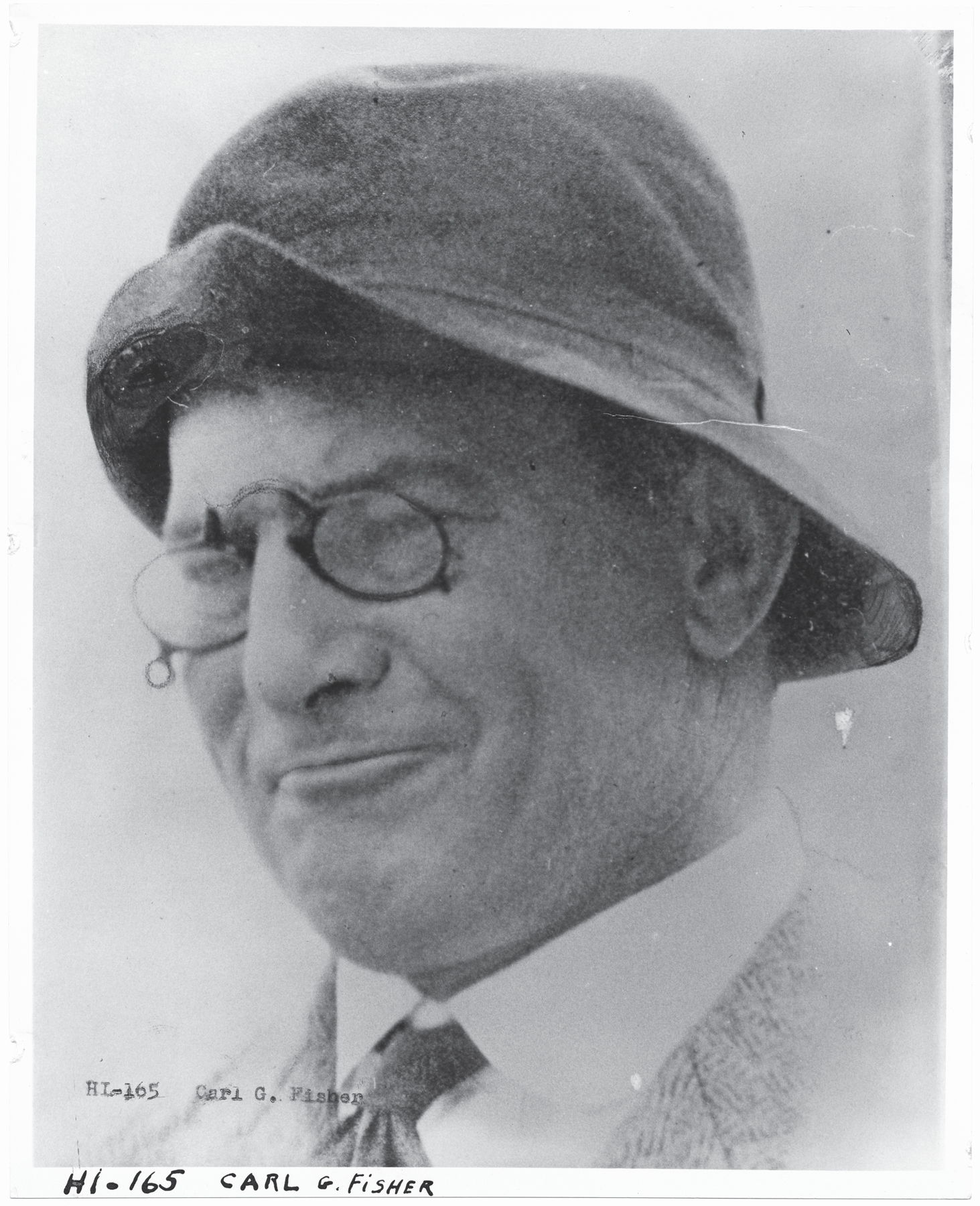

In the 1890s, around the same time Tuttle was coaxing Flagler to build a railroad to Miami, the first speculators arrived on Miami Beach. The most important one was a New Jersey farmer named John Collins (the namesake of today’s Collins Avenue, a main thoroughfare in Miami Beach), who bought several hundred acres of the island for next to nothing, cleared some land, and planted 38,000 coconut trees, thinking he would make a fortune. It turned out to be a failure. He then planted 2,945 avocado trees, and they did a little better. But the most notable thing Collins did was start building a bridge from Miami, across Biscayne Bay, to the sandbar, thinking it would draw in people and make land more valuable. And the most notable thing that did was capture the attention of Carl Fisher, a daring speed-obsessed Midwestern entrepreneur who got rich from his patent and manufacturing of the first mass-produced automobile headlight and helped create the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the first transcontinental highway. But mostly, Fisher was a huckster and a promoter who saw the potential of transforming Miami Beach into America’s winter playground. Fisher gave Collins the money to finish the bridge in exchange for several hundred acres of seemingly worthless swampland.

Carl Fisher in Miami Beach, 1923. (Photo courtesy of Miami Beach Digital Archives)

It was an insane project, as Fisher’s wife, Jane, immediately understood when he took her out to inspect his new real estate. “Creatures that made me shudder were lying in wait on the branches of the overhanging trees,” she recalled. “The jungle was as hot and steamy as a conservatory. The mosquitoes were biting every exposed inch of me. I refused to find any charm in this deserted strip of land. But Carl was like a man seeing visions. He picked up a stick, and when we reached the clean sand he began to draw a plan. I know now that he was seeing Miami Beach, in its entirety, rising from that swamp.”

Fisher hired hundreds of black laborers to hack away the palmetto and mangroves. Then he filled in the marshy land with sand dredged from the bottom of Biscayne Bay. He brought in colossal steel-hulled dredgers, one of which had on board its own complete machine and repair shop and its own ice plant. It had a 1,000-horsepower engine that pushed the sandy bay bottom to the surface through a twenty-inch pipe. It could move 20,000 cubic yards of fill in twenty-four hours.

The fill was a mixture of sand, mud, and marl, resembling “sloppy Cream of Wheat,” as one observer described it. Men worked in mud and slime up to their knees, wearing long boots to guard against snakebites. One of the first jobs was to transform Bull’s Island, where the Collins Bridge ended, so that the road could be built out to the beach. One of the dredgers pumped 300,000 cubic yards of sand on Bull’s Island in four days’ time, creating acres of land. For aesthetic reasons, the island was renamed Belle Isle in 1914 (today, Belle Isle is populated by condo towers, as well as the Standard, a hip hotel and spa where you can buy vibrators in the hotel gift shop). The “soup” had to drain and thicken before anything could be done with it. For six months, it was left undisturbed so that the algae and marine life could dry or rot away and the smell could dissipate.

Hard borders had to be built to keep it all from washing away. Pile drivers sank supports for pilings, to which wooden timbers were attached with steel cables. Thousands of tons of rock were loaded onto barges in the center of the state, then floated down a drainage canal that went from Lake Okeechobee to Miami and across Biscayne Bay, where they were unloaded at a wharf and hauled by mules around Miami Beach. As one observer put it: “The bayside gradually began to look as if it were covered by a glittering, hard-packed layer of snow standing five feet above the tide.” To keep the new land from blowing away, mulch from the Everglades was brought in by barge, spread, and graded. Jane Fisher remembered: “Hundreds of Negroes, most of them women and children, crawled on their hands and knees over the earth pushing ahead of them baskets of grass from Bermuda.” Gradually, the wild island was tamed, made suitable for people motoring down from the Midwest.

A few miles up the coast, in Fort Lauderdale, Charles Green Rhodes, a West Virginia coal miner from a family of twelve, dredged a series of canals along the New River, then used the fill to create rows of small peninsulas that stretched into the river like grasping fingers. This way every lot on every street backed up to a canal and thus could be sold as waterfront. Rhodes named the development the Venice of America and made millions. His canal-building technique, dubbed finger-islanding, quickly caught on, and it took years before anyone realized that the canals became stagnant cesspools and the development destroyed the habitat of manatees and other wildlife. Or that the houses would sink into the muck. Or that, in the twenty-first century, as sea levels started to rise, the phrase the Venice of America would take on an entirely different meaning.

There was so much money to be made it was almost comical. A veteran who had swapped an overcoat for ten acres of beachfront after World War I found the property worth $25,000 during the boom. A screaming mob snapped up 400 acres of mangrove shoreline in three hours for $33 million. “Hardly anybody talks of anything but real estate, and… nobody in Florida thinks of anything else in these days when the peninsula is jammed with visitors from end to end and side to side—unless it is a matter of finding a place to sleep,” said the New York Times. In 1916, Fisher’s company sold $40,000 worth of real estate; nine years later, in 1925, the company sold nearly $24 million. By then, there were 56 hotels with 4,000 rooms in Miami Beach, 178 apartment houses, 858 private residences, 308 shops and offices, 8 casinos and bathing pavilions, 4 polo fields, 3 golf courses, 3 movie theaters, an elementary school, a high school, a private school, 2 churches, and 2 radio stations.

In 1925, humorist Will Rogers described Fisher as “the first man smart enough to discover that there was sand under the water. So he put in a dredge, and he brought the sand up and let the water go to the bottom instead of the top. Carl discovered that sand would hold up a real estate sign, and that was all he wanted it for.”

Of course, the boom went bust. The Internal Revenue Service investigated Florida speculators, the Better Business Bureau exposed Florida con artists, journalists touted Florida scandals. And then, as if Mother Nature were getting her revenge for the blasting and draining of South Florida, at about 2 a.m. on September 18, 1926, a Category 4 hurricane slammed into Fisher’s newly minted paradise. “Miami Beach was isolated in a sea of raving white water,” journalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas wrote. Winds hit 128 miles per hour, turning utility poles into flying spears. Roofs Frisbeed off buildings. A ten-foot storm surge flooded Miami Beach. Homes floated off their foundations. When the water retreated, the streets were covered in sand, as were lobbies of swanky oceanfront hotels. The hurricane’s final toll: 113 people dead, 5,000 homes destroyed or damaged.

In retrospect, none of this was surprising. The whole DNA of the Florida boom had been about making a quick buck. Nobody was thinking about resiliency; nobody was pausing to consider the consequences of building a city on the water right in the middle of a well-known hurricane path. The houses were flimsy, the wiring bad, the bridges fragile, the roads right along the water. Who cared? This was Miami Beach. There was no government oversight, no long-range planning. The only future that mattered was the next cocktail, the next beautiful sunset, the next riff in the jazz club.

And it wasn’t just in Miami where flimsy construction proved to be dangerous. The 1926 hurricane pushed water through a poorly built earthen dike that held in Lake Okeechobee in the central part of the state, flooding the farmlands below the lake and killing four hundred people. Two years later, another hurricane hit, taking out an even bigger part of the still-flimsy dike and sending a fifteen-foot tsunami through the same farmland. This time, more than twenty-five hundred people died, mostly poor blacks who drowned in the vegetable fields of the Everglades.

Eventually, changes were made. The City of Miami passed the first building code in the United States (it later became the basis for the first nationwide building code). It required roofs to be bolted down, building frames to be securely attached to foundations, windows to have hurricane glass. The building codes have been upgraded over time, and Miami—like most modern cities—is far more resistant today to hurricanes than ever before.

But the legacy of cheap building in South Florida persists. You could see it in the devastation caused by Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which flattened Homestead, a region just south of Miami: $26 billion in damage, 65 people dead, 250,000 homeless. During my travels in South Florida, I learned that the concrete used in the much-beloved Art Deco buildings in South Beach was often mixed with salt water or salty beach sand, which can cause the rebar within the concrete to corrode over time and greatly weaken the concrete. While renovating a South Beach hotel, one architect I know discovered that the structural walls were so weak that you could practically knock them down with a hammer. Instead of continuing with the renovation, they had to tear down everything but the façade and rebuild it to modern standards. How many other old Miami buildings suffer from the same weakness? Leonard Glazer, an electrical engineer and lighting designer who worked in Miami Beach in the 1950s and 1960s and was responsible for the spectacular lighting at the Fontainebleau and the Eden Roc hotels, laughed when I asked him about building codes: “There was no code! Or if there was, nobody paid any attention to it. Your job was to do the work quick, and do the work cheap. In Miami Beach, nobody was thinking about the long term.”

The 1926 hurricane also laid bare the combination of boosterism and denial that drove—and still drives—South Florida politicians and business leaders. Carl Fisher first articulated the Florida dream of sunshine, beaches, and fun (or, as one Florida journalist wrote in 2016, “Miami Beach has based its economy on the fact that strangers love to visit and get drunk there”). Fisher used elephants and girls in bikinis and teams of PR pros to manufacture paradise. Real estate was always a good investment; the sex was always better, the climate always perfect. And hurricanes? In 1921 a newspaper ad inviting tourists and investors to Miami Beach promised there was “practically no danger from summer storms.” Of course, summer storms and hurricanes had been sweeping through South Florida for thousands of years.

After the hurricane hit, denial went into overdrive. Miami business leaders were terrified that hurricane publicity would scare away visitors and investors. Florida’s leaders minimized the damage, denying reports of devastation as rumors and exaggerations, openly discouraging relief efforts. When a city editor at the Miami Herald filed a story reporting $100 million in damage, his boss ordered the losses reduced to $10 million. Miami’s mayor declined offers of outside aid, and the governor insisted that life was quickly returning to normal. The chairman of the Red Cross charged that “the poor people who suffered are regarded as of less consequence than the hotel and tourist business in Florida,” but official spin continued to portray the storm as a minor inconvenience in paradise. One booster took out full-page ads in the Herald pointing out that Florida was still perfectly positioned for growth, that the big blow was nothing compared to floods in the Midwest, “winter diseases” in New England, or earthquakes in California: “Sure, some lives were lost in the hurricane, but hurricanes come only once in a lifetime.”

Carl Fisher and other early Florida developers may have been greedy quick-buck artists, but they knew something about defeating nature in pursuit of pleasure. They understood that no matter how mosquito-and-alligator-infested a swamp may be, you can drain it, dredge it, and make a fast dollar. No matter how big the hurricane, you can always rebuild. More than any place in America, South Florida has been an expression of the technological dominance of twentieth-and twenty-first-century life: it is a world created by dredgers, cooled by air conditioning, powered by nuclear energy, dominated by cars, sanitized by insecticides, glamorized by TV and the Internet. It is a place that has been habitable only if you believe the premise that nature—the heat, the bugs, the alligators, and most of all, the water—can be tamed.