7. WALLED CITIES

ON A BRIGHT spring day, I walked along the seawall on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with Dan Zarrilli, the head of New York City’s Office of Resilience and Recovery—basically, he was Mayor Bill de Blasio’s point man for preparing New York City for the coming decades of storms and sea-level rise. Zarrilli, who is in his early forties, was dressed in his usual City Hall attire: white shirt and tie, polished black shoes. He had short-cropped gray hair, dark eyes, and an edgy I’ve-got-a-job-to-do manner. Zarrilli may be the only person in the world who holds in his head the full catastrophe of what rising seas and increasingly violent storms mean to one of the greatest cities in America. Not surprisingly, instead of musing about the beautiful weather, he pointed to the East River, where the water was innocently bouncing off the seawall about six feet below us. “During Sandy,” he said darkly, “the storm surge was eleven feet high here.”

As Zarrilli knows better than anyone, Hurricane Sandy, which hit New York City in October 2012, flooding more than 88,000 buildings in the city, killing 44 people, and causing over $19 billion in damages and lost economic activity, was a transformative event. It did not just reveal how vulnerable a rich, modern city like New York is to a powerful storm, but it also gave a preview of what the city may face in the coming century. “The problem for New York is the same as it is for every coastal city,” Chris Ward, the former executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the agency that runs New York’s airports, tunnels, and other transportation infrastructure, told me. “Climate science is getting better and better, and storm intensity and sea-level rise projections are getting more and more alarming. It fundamentally calls into question New York’s existence. The water is coming, and the long-term implications are gigantic.”

Zarrilli turned away from the water and we walked toward the downtrodden park that separates the river from the FDR Drive, and, beyond that, the Lower East Side. “One of our goals is not just to protect the city, but to improve it,” Zarrilli explained. In 2018, the city planned to break ground on what’s called the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, a ten-foot-high steel-and-concrete-reinforced berm that will run about two miles from East Twenty-Fifth Street down to the Manhattan Bridge. The project, which is budgeted at $760 million but will surely cost far more before it’s completed, is the first part of a larger barrier system, known informally as the Big U, that someday may loop around the bottom of Lower Manhattan. Unlike the MOSE barrier in Venice, if and when the Big U is ever completed, it will be a solid wall—a modern rampart against the attacking ocean. There are plans in the works to build other walls and barriers in the Rockaways and on Staten Island, as well as across the river in Hoboken. But the Big U in Lower Manhattan is the headliner, not just because it will cost billions to construct (rough estimates start at $3 billion and rise fast), but also because Lower Manhattan is the most valuable chunk of real estate on the planet, as well as the economic engine for the entire region—if it can’t be protected, then New York City is in deep trouble.

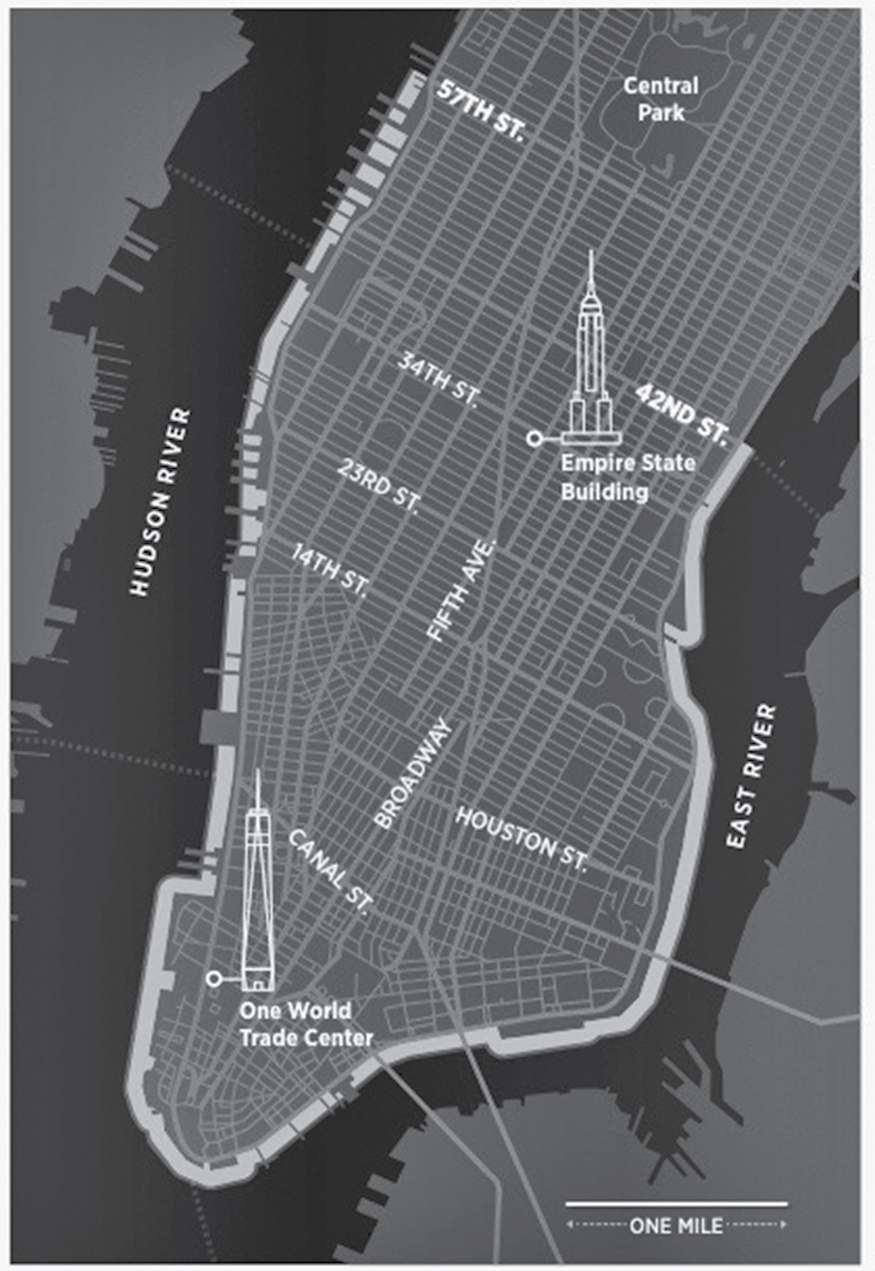

The Big U in Manhattan, from E. 42nd St. around to W. 57th St. (Map courtesy of John Grimwade)

Zarrilli, who doesn’t like the phrase “Big U” because it sounds like a plug for BIG, the Danish architectural firm that helped design the barrier, was uneasy talking about walls, in part because that obscures other, more democratic measures the city is taking to become more resilient, such as requiring developers to elevate critical infrastructure and install robust backup power generation, but also because wall-building is politically fraught: You can’t wall off the city’s entire 520-mile coastline, so how do you decide who gets to live behind the wall and who doesn’t? “You have to start somewhere,” Zarrilli explained, “so you begin in the places where you get the maximum benefit for the most people.”

In Zarrilli’s view, there is no time to waste. He knows as well as anyone that even the most indomitable city in America is facing a brutal future of rising seas and increasingly violent storms. As we crossed the FDR Drive on a pedestrian overpass, I asked Zarrilli, who is the father of two young kids, if it scared him to think about the economic and political chaos that may be coming. “It’s not a pretty picture, but you can’t let yourself be paralyzed by fear,” he said, putting a brave face on it. “You have to take it one step at a time and do what you can right now.”

When it comes to sea-level rise, few cities have more at stake than New York. In purely economic terms, the New York metropolitan area is responsible for nearly 10 percent of the US gross domestic product and is the financial hub of the free world. The city also has a symbolic value that is hard to quantify, with 8.5 million people from all over the world living there, and billions more who are connected to the city by work or family or by their dreams to come here and make it big. “To deal with climate change, we need inspiration,” said Henk Ovink, the Dutch special envoy for international water affairs, who was deeply involved in rebuilding New York after Sandy. “New York City is the capital of the developed world. If it does things right, it can radiate inspiration to everyone.”

In a world of rapidly rising seas, New York is better prepared than many coastal cities. As anyone who has seen the rock outcroppings in Central Park knows, much of Manhattan is built on five-hundred-million-year-old schist, which is impervious to salt water. There is plenty of high ground, not just in Upper Manhattan’s Washington Heights, but also along a ridge that runs diagonally through Queens and Brooklyn, including places like Jackson Heights and Park Slope. Finally, the city has brains and money and attitude—New York is not going to go down without a fight.

But in other ways, New York is surprisingly at risk. First, it’s on an estuary. The Hudson River, which runs along the west side of the city, needs an exit. So unlike with a harbor city like, say, Tokyo, or a city on a lagoon like Venice, you can’t just wall New York off from the rising ocean. Second, there are a lot of low areas, including the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts and Lower Manhattan, which have been enlarged by landfill over the years (if you compare the map of damage from Sandy in 2012 with a map of Manhattan in 1650, you’ll see that they match pretty well—almost all the flooding occurred in landfill areas). The amount of real estate at risk in New York is mind-boggling: 72,000 buildings worth over $129 billion stand in flood zones today, with thousands more buildings at risk with each foot of sea-level rise. In addition, New York has a lot of industrial waterfront, where toxic materials and poor communities live in close proximity, as well as a huge amount of underground infrastructure—subways, tunnels, electrical systems. Finally, New York is a sea-level-rise hotspot. Because of changes in ocean dynamics, as well as the fact that the ground beneath the city is sinking as the continent recovers from the last ice age, seas are now rising about 50 percent faster in the New York area than the global average.

Building fortifications around a city is an idea that is as old as cities themselves. In the Middle Ages, walls were built to keep out invading armies. Now they are built to keep out Mother Nature (or, in Trumpland, illegal immigrants). Obviously, if they are built right, they work. Seventy percent of the Netherlands is below sea level; without walls, dikes, and levees, the nation would be a kingdom of fish. New Orleans exists today only because of enormous levees holding back the sea. Japan is practically encircled by giant seawalls to protect residents from tsunamis. But even among the Dutch, the masters of Old World–style levee-building, walls and dikes and levees are falling out of favor. “We are beginning to realize we can’t keep building walls forever,” said Richard Jorissen, the Dutch expert who took me out to see the Maeslant Barrier near Rotterdam. “Sometimes they are necessary, but we also understand that sometimes we have to learn to live with the water. If it is not built right, a wall can create as many problems as it solves.”

As far as walls go, the Big U was designed to be a nice one. It’s the love child of a collaboration headed by the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), the Danish firm that has designed a number of playful, slightly surreal buildings around the world (including a pair of condos in Miami for developer David Martin).

The Big U was one of four winning proposals in the $930-million Rebuild by Design competition, which was sponsored by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development in the aftermath of Sandy and attracted proposals by top architects and urban planners from around the world. In an animated video that BIG created to promote the project, the Big U is depicted as an undulating public space where a grass berm is planted with flowers and trees and creates parklike areas where people can play baseball and stroll on a sunny day. The gritty, thundering empty space beneath the elevated FDR Drive is transformed into a place where kids play Ping-Pong and farmers’ markets appear on weekends. The city is protected from the water by the berm (which is underlaid with steel and concrete) and walls covered in art that flop down from the FDR. It is all very cheerful and inspiring—disaster-proofing as a public amenity.

The problem is, the actual barrier may or may not resemble the barrier in the video. Several urban planners I talked to believe that, due to cost-cutting and engineering complexities, by the time it is built, the wall will be stripped of its crowd-pleasing amenities. “When it’s done, it’s just going to be a big dumb wall,” said one landscape architect who has watched the project closely.

But dumb or not, given the amount of valuable real estate in Lower Manhattan, some kind of defensive structure is going to be erected there to keep the water out. Building a wall is (compared to more long-term and nuanced options) cheap, quick, and irresistible to politicians wanting to prove they have acted boldly. But that doesn’t mean it’s always the smartest or the safest solution.

For one thing, as the flawed assumptions behind the design of the MOSE barrier in Venice have revealed, there’s always a question about what level of protection the barrier is designed to provide. Residents of Kamaishi, Japan, thought they were safe behind a mile-long, twenty-foot-high steel-and-concrete seawall. But when a thirty-foot-high tsunami hit the region in 2011, the seawall crumbled and 935 Kamaishi residents died. Lower Manhattan and Japan are not directly comparable, if for no other reason than the fact that Lower Manhattan is not exposed to tsunamis. But whenever you build a wall, there is always the risk that Mother Nature won’t respect the design specifications. A barrier like the Big U would in theory be designed to protect from another Sandy, but not a lot more. (And by 2100, Sandy-like events are predicted to occur much more often.) I asked Kai-Uwe Bergmann, a partner at BIG, why the barrier wasn’t designed to withstand a Sandy-level flood plus, say, an additional five feet to accommodate sea-level rise in the future: “Because the cost goes up exponentially,” he replied bluntly and honestly.

Another obvious problem is that walls only protect the people who are behind them. The new barrier on Lower East Side will have the virtue of protecting several large public housing developments, as well as a key Con Edison substation that flooded during Sandy, causing a massive blackout in Lower Manhattan. But that barrier is likely to be just the beginning of the walling-off of Lower Manhattan. “The real purpose of the Big U is to protect Wall Street,” said Klaus Jacob, a disaster expert at Columbia University. Given the importance of Wall Street to the US economy, that was not surprising. But how long do you think it will be before Red Hook, a largely poor, African-American area in Brooklyn that was also heavily damaged by Sandy, gets a barrier designed by Bjarke Ingels?

Across the Hudson River from New York City in Hoboken, New Jersey, walls posed a different problem. Much of Hoboken was built on former wetlands; when Sandy hit, water poured in like it was filling a giant bowl (one of the most iconic images of Sandy was of a sailboat beached in front of luxury apartments in Hoboken, across which someone had spray-painted GLOBAL WARMING IS REAL). To protect the city, Mayor Dawn Zimmer supported building a Big U–like barrier along the waterfront. The problem is, to protect the city, the wall has to run in front of luxury lofts with prized views of Manhattan. “I’d rather flood than stare at a wall,” one Wall Street analyst who lives along the waterfront told me. Zimmer, who, during a recent walk through the city, was obviously frustrated by the politics of the debate over the barrier, had proposed routing it through an alley behind the luxury lofts. The new route would leave about thirty-five buildings—some of the most expensive real estate in Hoboken—exposed to rising waters and storm surges. “If they don’t want to be part of this, they can take care of themselves,” Zimmer told me.

In some cases, walls just make water problems worse. Half a world away, in Bangladesh, building walls and embankments have actually exacerbated flooding in parts of the massive Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta. To protect their land, some farmers have built embankments along tidal channels. In doing so, however, they have inadvertently channeled the water deeper inland, causing a huge increase in flooding and saltwater contamination of less-protected areas. Similarly, a wall around Lower Manhattan might actually deflect more water into places like Red Hook, said Alan Blumberg, an oceanographer at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken. “It might keep water out of Manhattan, but it could make the problem worse for people in Brooklyn, not better.”

There is also the question of complacency. Walls, dikes, and levees make people feel safe, even when they are not. When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, many people didn’t evacuate because they assumed the levees would not fail; that assumption cost some people their lives. In 2008, when a typhoon hit China’s Pearl River Delta, one third of the granite seawalls in Zhuhai crumbled, letting water flood into the city. “Walls often make people stupid,” said Richard Jorissen. “They allow you to ignore the risk of living in dangerous place—if something goes wrong, it can be a catastrophe.”

There were other, less brutal ideas for how to protect Lower Manhattan. Even before Sandy hit, a team headed by New York landscape architect and urban designer Susannah Drake proposed elevating the edge of Lower Manhattan about six feet, waterproofing utilities in vaults under the sidewalks, and raising and redesigning streets to allow them to hold water during floods. The waterfront would be softened with salt marshes and wetlands to absorb wave energy and clean storm water. To finance this new infrastructure and blend the elevated city into the waterfront, Drake’s plan allowed for a row of new towers to be built along the East River. All in all, it was an elegant reimagining of Lower Manhattan in a world of rising waters. But projects like this are nuanced and complex and expensive, making them difficult to sell as a quick fix. And they require people to acknowledge that the world is changing fast and that they will live differently in the future. It’s so much easier to just build a wall and forget about it—“until a big storm comes along and washes away the wall,” Drake said. “Then you have a disaster.”

One of the most innovative proposals to come out of the post-Sandy Rebuild by Design competition was called Living Breakwaters, which received $60 million in federal funding. The project was designed by SCAPE, a design firm in New York City founded by Kate Orff, who gained notoriety a few years ago with a bold proposal to clean up New York City’s harbor by reintroducing oysters. Her Living Breakwaters project, which will be built on the south shore of Staten Island near the town of Tottenville, is a four-thousand-foot-long system of breakwaters located about a thousand feet from shore. It is not designed to stop sea-level rise. It is designed to slow and soften waves before they hit the coast, lessening the impact of storms and slowing erosion. The breakwaters themselves will be built with ecological features like textured concrete units that make healthy habitats for young fish. They will also be seeded with oysters to help further slow and clean the water. Instead of cutting the community off from the waterfront with a fortresslike wall (“the era of big infrastructure is over,” Orff says bluntly), Orff wants to engage the community with the coastline again. Among other things, SCAPE hopes to work with schools to help garden oysters and start collection programs for shells that could be added to the breakwater to strengthen its growing ecosystem. “Sustainability and resiliency can be built, but by reconnecting with our shorelines, not walling off the 500-plus miles of the city’s coastline,” Orff wrote in the New York Times.

Perhaps the boldest proposal for protecting the city was the Blue Dunes, a forty-mile chain of islands that a group of scientists and architects proposed building in the shallow water about ten miles off the coast. From the city, the dunes would have been invisible, but together they would have formed a protective necklace of sand running from Staten Island up to Long Island. Like SCAPE’s Living Breakwaters, the Blue Dunes were designed to absorb the wave energy of the Atlantic before it hits the city, lower the impact of high tides, and buy the city time to recalibrate for sea-level rise. But whereas Living Breakwaters is modest in ambition and human in scale, the Blue Dunes, proposed by a group headed by Dutch landscape architect Adriaan Geuze, would have reshaped the entire coastline of New York City. The Blue Dunes would not save the city from sea-level rise, but they might save New Yorkers from fearing sea-level rise, showing them that there are ways, as Geuze has put it, of “working with nature, bending its will, rather than trying to punish it.”

The Blue Dunes provoked a lot of discussion during the Rebuild by Design competition, but in the end, the project was not funded.

New York City mayor Bill de Blasio does not have a reputation as a visionary leader. But on climate change, he has a solid record, despite the fact that it’s not an issue that de Blasio came to himself. It was forced on him by Sandy, which hit the city just as the mayoral election was getting under way in late 2012. Michael Bloomberg, New York’s mayor at the time, had long been pushing climate change, including a landmark study called PlaNYC, a twenty-five-year plan for a greener city that he released in 2007. De Blasio, a former city councilman and political operative (he managed Hillary Clinton’s New York Senate campaign in 2000), was interested in education and economic inequity. But after Sandy hit, de Blasio, who was living in Park Slope, Brooklyn, at the time, got schooled in the dangers of climate change and extreme weather. To his credit, de Blasio immediately understood that Sandy did not treat everyone equally. He told the New York Times a few months after the storm, “You can look at this as ‘We need seawalls,’ or you can look at this as ‘We need to retool our approach for human security, economic security, for economic equity.’”

Rebuilding the city after Sandy was a joint city, state, and federal project. Almost all the funds came from a $60-billion federal disaster relief appropriation from Congress, which has been doled out through the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to various state and local agencies. Shaun Donovan, who was head of HUD at the time, is a native New Yorker and is widely praised for his response to Sandy. But rebuilding from Sandy is not the same as rebuilding for the city’s long-term future. And in that, the city has had very little help from Washington, much less from the state capitol in Albany. New York governor Andrew Cuomo has put some muscle into greening the state’s energy grid, but the reconstruction of New York City didn’t earn much of his attention (within City Hall, many believed it was personal—Cuomo, who thinks of himself as the big dog in New York State Democratic politics, didn’t want to do anything to make his archrival de Blasio look good). In the aftermath of Sandy, Cuomo commissioned a high-level study about how to make the state of New York more resilient to climate change—then hardly mentioned it again after it was complete. Some of his pet projects, such as a $4-billion proposal to renovate the aging LaGuardia Airport, which is in a high-risk flood zone, make no sense in a world of rapidly rising seas.

With a checked-out governor, de Blasio’s leadership is all the more vital. I met with him on Earth Day in 2016, just after he made a brief speech at the United Nations to celebrate the signing of the Paris climate agreement. In his speech, he rightfully touted the city’s progress in improving building efficiency and purchasing more renewable power, among other CO2-reduction measures. De Blasio deserves a lot of credit for pushing hard to shrink the carbon footprint of New York, and he often speaks convincingly about the implications of climate change for the poor and working class, but I wondered if maybe it was time for some strategic thinking about the long-term survival of the city too. Stuff like: Was it time to consider moving the city’s airports to higher ground? How about creating economic incentives to encourage people to move out of low-lying areas of the city? If it takes New York City fifty years to construct a single new subway line, what hope is there of rebuilding the waterfront of the city in time to deal with rising seas?

De Blasio resisted my line of questioning, preferring to focus on the climate challenges the city faces today and tomorrow. “I think the simple way to think about it is right now we have to do the most immediate resiliency measures to secure us against the kind of storms we’d have,” he told me. “Then you want to just keep going, and building up, building up, and trying to stay ahead of what will be a growing problem. But to me it’s literally like, block by block by block. Complete this phase and you roll immediately into the next. This has to be a priority of government perennially until we build a very, very different world.”

I said, “When you look at flood maps that project five, six feet of sea-level rise… it’s a pretty apocalyptic scenario for New York, isn’t it?”

“Yeah. At the end of the century, true.”

“That’s not that long from now,” I replied.

“Yes it is,” he argued.

“Your grandkids will still be here.”

“Yeah, but as a public policy matter, if you’re talking seventy-five, eighty, or more years in the future, I think it’s very, very responsible to say, ‘Okay, first let’s deal with the needs of people right now,’ and that is both about resiliency and environmental concerns, but it’s also, the totality of human need. If we don’t have that in the foreground, there’s something wrong with us. Right?”

True to his word, in the months after de Blasio and I talked, the city released new guidelines to encourage architects and engineers to identify design elements that could reduce the risk of flooding from future sea-level rise, including elevating new buildings by as much as three feet and erecting site-specific flood barriers. The guidelines are not part of the city’s building code yet, but perhaps in a few years they will be. That was yet another step down a long and increasingly wet road.

Klaus Jacob was Hurricane Sandy’s Cassandra. Jacob is a retired research scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, where he spent forty years researching earthquake prediction science and disaster relief. For the last decade or so, he had been deeply involved in shaping New York’s response to rising seas as a member of the city’s task force on climate change. At eighty, he still spoke with a hint of a German accent and had a bratty twinkle in his eye (five minutes after we met, he mentioned that he used to hang out with 1960s black activist Angela Davis).

A few months before Sandy hit, a Columbia University research team headed by Jacob released a case study estimating the effects of a 100-year storm surge on New York’s multibillion-dollar transportation infrastructure. Jacob told anyone who would listen that the combination of rising seas and a particularly powerful storm could wreck the city’s trains and subways, flooding tunnels and submerging aboveground equipment. As it turns out, that’s exactly what happened when Sandy blew through. The subways were out of commission for days, and it took weeks before a system that serves millions of commuters was fully back online. Thanks in part to Jacob’s warnings, New York officials shut down the subway before Sandy arrived, limiting the damage.

Jacob was critical of de Blasio and others for not thinking big enough about what kind of future the city faces. “They are thinking on an election time scale,” Jacob said. He cited the continued development of waterfront property in Manhattan, Cuomo’s plans to renovate the terminals at LaGuardia Airport, and Columbia University’s new Manhattanville campus, which is located on low ground on the West Side near 125th Street. “We still allow development on the waterfront to take place where fifty, eighty years from now it will be regretted,” Jacob told me. Even businesses that should know better are failing to grasp what’s coming. Jacob pointed out that Con Edison, the utility that powers most of the city, proposed spending $1 billion on rebuilding after Sandy without taking climate change into account (that changed after ratepayers filed suit against the company; Jacob was a technical consultant in the case).

In Jacob’s view, New York’s Achilles’ heel is the subways, which are particularly vulnerable because the tunnels need fresh air for ventilation and can’t be sealed off. And although the subway tunnels are designed to handle flooding from freshwater, salt water is highly corrosive to electrical circuits, as well as to the concrete in the tunnels (that’s a big reason why the L train will be shut down for more than a year of repairs). In theory, the ventilation ducts can be raised, and barriers can be erected to keep seawater from pouring in during storms, but at some point, the cost gets prohibitive. “It’s all about money,” former Port Authority chief Chris Ward told me. Ward pointed out that the Metropolitan Transit Authority, which operates the New York subways, spent $530 million upgrading the South Ferry station in Lower Manhattan after the old one was heavily damaged during the attacks on September 11, 2001. After Sandy turned the new station into a fish tank, the MTA put the old station back into service while it spent $600 million to fix the new station. The MTA has installed removable barriers to stop seawater from flooding the new station in the next big storm, but the subway system remains highly vulnerable to rising seas. “We’re not thinking systemically about climate change,” said Michael Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School. “It’s not just about the next Sandy, as if Sandy were the worst thing that could happen.”

Back in the 1920s, developers discovered a spit of land out in Jamaica Bay where cops and firemen and plumbers and other working-class folks from Manhattan had set up weekend fishing camps. The shallow bay in Queens was full of crabs and bluefish and bass. Occasionally a dead horse might float by, dumped in the bay by someone who didn’t want to pay to have the animal hauled off, but nobody thought much about it. Many of the structures on the sandy island were just wooden shacks that would wash away whenever a big storm hit. The people who owned them didn’t care, they just hammered together a new shack and went fishing again. It wasn’t much different from the way the Calusa lived in South Florida with their palapas and shell middens five hundred years ago.

Before long, developers came and dredged the channels in the island, thinking it would add to the appeal of the place if homeowners could dock their boats in their backyards. Then they put up houses, real houses with concrete foundations and insulated walls and septic systems. They gave the place a name—Broad Channel. Many of the cops and firemen gave up their shacks and settled into the new homes as permanent residents. They had a view of Manhattan and could go fishing after work. What was not to like? They knew they might get hit by an occasional storm but believed that the Rockaways—a much bigger barrier island to the east—would protect them from the worst of it. As for rising seas—back then, that was something that happened only in science fiction novels.

One family who bought a house in Broad Channel in the 1920s was the Mundys. When I visited in 2016, Daniel Mundy, who had been born in Broad Channel and was now in his late seventies, lived in a house right on the water. His son, Daniel Mundy Jr., who was in his early fifties, lived across the canal, also facing the water. When Hurricane Sandy hit, they were lucky—they got five feet of water in their homes, but the houses suffered little structural damage. Others were not so lucky. Broad Channel was one of the most heavily damaged areas of the city—more than 1,200 homes were flooded; over 400 needed to be torn down and completely rebuilt. Others have been repaired and elevated.

“We were really hammered,” Dan Mundy Jr. said, standing in the living room on a sunny day, the towers of Manhattan glinting in the distance. Mundy was a battalion chief with the New York City Fire Department, an earnest, muscular guy who knew how to pull the levers and switches in the New York political system.

Standing on his rear deck, Mundy pointed at two narrow islands that he and his friends in Broad Channel built out in the bay (with the help of the US Army Corps of Engineers) to help bring down nitrogen levels and improve fish habitat. Thanks in part to the work of people like Mundy, one of the most important bird estuaries on the East Coast and a spawning ground for horseshoe crabs is making a comeback.

Mundy was well aware of the risks of sea-level rise. I asked him if he ever thought about leaving.

“Both my parents were born here,” he said bluntly. “I grew up here. My sister lives here. I’ve scuba dived under the piers in the bay five hundred times. Why would I leave? This is my home.”

Many others I talked to in Broad Channel felt the same way. They were staying there come hell or high water. And the Army Corps of Engineers helped perpetuate the idea that sticking around was a viable alternative by fast-tracking a protection plan for the entire Jamaica Bay. The $2-billion project would reinforce the dunes that face the ocean on Rockaway Beach, raise seawalls in the bay, and erect a movable barrier across the inlet that could close to protect from a storm surge. Basically, it was a dumbed-down version of the MOSE barrier in Venice. And it had all the same problems: it was hugely expensive, it would take decades to build, and by the time it was built, it could very well be obsolete. But if you wanted to buy the people who lived around Jamaica Bay a little more time, there weren’t many other options. Some neighborhoods around the bay, such as Howard Beach in Queens, were particularly problematic, with rows of brick homes with basements built in low-lying areas that are virtually impossible to elevate.

Later that night, I went to a community meeting, where Dan Falt, the project manager for the Army Corps of Engineers, laid out the gist of the plan for the first time to members of the community. Falt, who lives in a bungalow on Rockaway Beach, worried that the plan was going to be controversial—even though, strictly speaking, the plan was nothing new. The Army Corps of Engineers had proposed a nearly identical plan to protect the bay back in 1964; they just made a few tweaks for 2016.

But if this meeting was any indication, people who live around Jamaica Bay didn’t care about how old the plan was. They wanted protection. Or at least, the illusion of protection. And they believed it was the government’s role to provide it for them. Who cared if the barrier turned the bay into a big pond? The basic view of people who spoke up at the meeting could be summed up like this: It’s nice to have birds and marine life, but it’s even nicer to have a home—if only for a few more decades. There was no talk about living with water, about elevating homes, about commuting by boat. Nor did anyone entertain the idea that maybe the smart thing to do was to get out while they could and move to higher ground. As one woman said, standing up in the back of the room with a hint of panic in her voice, “What I want to know is, how long is it going to take to build these walls? How long are we going to be vulnerable? One more big flood, and we are toast.”

An hour later, I walked back to my car, which was parked on the street near Mundy’s house. It was high tide—and the street was flooded. The full moon hung above me, indifferent to the complications its gravitational pull was causing for New Yorkers. I took off my shoes and socks, rolled up my pant legs, and waded through the cold, briny Atlantic to my car.