11. MIAMI IS DROWNING

SUNSET HARBOUR IS a neighborhood on the bay side of Miami Beach, which is the low side of the already low barrier island. A hundred years ago, it was a mangrove swamp. Today, million-dollar houses and condos have a romantic view to the west, over Biscayne Bay and toward the ever-changing towers in downtown Miami. Until recently, it was a not-so-hip area, with cheap 1950s apartments, muffler shops, and the City of Miami Beach’s only public boat ramp. A couple of big condo towers went up in the 1980s, but the neighborhood remained mostly forgotten until it was discovered by Scott Robins, a well-known Miami Beach developer, as well as his friend, Philip Levine, who had made a fortune selling specially produced magazine and TV shows to cruise ships and, like everyone else who made a small fortune in Miami, was trying to turn it into a larger fortune by dabbling in real estate development.

Robins and Levine brought in restaurants, coffee shops, and a new Publix supermarket. Old apartment buildings were torn down, new condos went up, and real estate prices boomed. But there was one problem: Sunset Harbour, more than most other places in the city, was prone to flooding during high tides or big rain events. Because it was on the low side of the island, high water tended to arrive there first and hang around for a while. In 2012, I visited Sunset Harbour during the annual king tides, which hit South Florida every year around mid-October. King tides are driven by a particular alignment of the sun and moon and Earth that maximizes the gravitational tug on the oceans, as well as changes in the Gulf Stream current and the way the heat of a long summer causes the ocean to expand. That October, I waded through water up to my knees in the streets of Sunset Harbour. Residents were enraged. The shop owners I talked to were on the verge of moving out. In fact, it was trudging through the water in Sunset Harbour that made me aware for the first time of the real-time risks Miami faced from sea-level rise.

Enjoying the high waters in Miami Beach. (Photo courtesy of Maxtrz/Creative Commons)

Not long after that visit, several things happened. The first was that cruise-ship-entrepreneur-turned-developer Philip Levine decided to run for mayor. He was a slick guy in his late forties, handsome, personally reserved but politically outgoing, and not afraid to knock on every door in Miami Beach and ask for a vote. He made flooding a central campaign issue, even managing to exploit it for laughs in a TV ad that showed Levine and his boxer, Earl, both of them outfitted with life jackets, kayaking through the streets of Miami Beach. Levine won the 2013 election, and suddenly, after much denial and bureaucratic foot-shuffling, the city began to take action on sea-level rise.

As it happened, the city had hired a new chief engineer named Bruce Mowry a few months before Levine took office. Mowry, a hard-charging Southerner who was sixty-three years old when he took the job, prided himself on his ability to get things done. At the urging of the mayor, he took a hard look at the city’s storm water master plan, which had been produced a few years earlier with the help of AECOM, a global engineering and consulting firm. In Mowry’s view, the plan understated the risks the city faced from higher tides and rising seas, but he got to work implementing the parts of the plan that would have the biggest impact first. In many areas of the city, flooding was caused by seawater backing up though the wastewater drainage pipes and bubbling up in the streets through manholes and sewer grates. To fix that, Mowry began installing one-way check valves on the drainage pipes that would stop the water from backflowing into the streets, as well as installing big pumps in low-lying areas of the city to drain the water that did accumulate. To finance all this, the city commissioners pushed through $100 million in bonds by raising the storm water fees on residents’ utility bills by about $7 (this was only a down payment—Mowry says the final price tag for the city’s flood abatement plans will likely rise to $500 million). In addition, Mayor Levine did what politicians always do when they are confronted with a politically complex issue—he formed a blue-ribbon panel and appointed a pal to oversee it. And who better for the job than Scott Robins?

Mowry and Levine spent most of 2014 working furiously to show progress on flooding in Miami Beach. Their goal was to show significant headway by the time the king tides hit the following October. Levine understood that because he had made sea-level rise such an issue in his campaign, his political future depended on his ability to deal with it. The media had caught on too. In 2013, I wrote a long story for Rolling Stone that highlighted the risks the city faced, and in the coming months, the Washington Post, the Guardian, and many other publications followed suit.

When the king tides arrived in 2014, it was clear that the mayor’s political gamble had paid off. The sea rose, but the check valves worked and the pumps sucked up the water. Sunset Harbour was mostly dry (it helped that the king tides were unexpectedly low that year, because of factors not related to sea-level rise). The mayor had invited a collection of dignitaries to a little park in Sunset Harbour to celebrate his accomplishments, including EPA administrator Gina McCarthy, Florida senator Bill Nelson, and Rhode Island senator Sheldon Whitehouse. They all praised the city’s efforts and used the occasion to call for deeper cuts in carbon emissions. In the world of climate change, it was one of those rare uplifting events. Yes, Miami Beach is in danger—but look what a little sweat and ingenuity can do!

A few days later, I went to see Robins at his office in South Beach. He was friendly and chatty, with the air of a Miami hipster who has recently become serious about civic matters. We talked for an hour or so about the challenges Miami Beach faced and how the city might deal with it in the future.

Two things were memorable about that encounter. The first was that, despite the fact that Robins was head of the mayor’s Blue Ribbon Panel on Flooding Mitigation, there was no danger that anyone would mistake him for a climate scientist. Case in point: when we talked about future rates of sea-level rise, he pulled out a tide chart from that week and remarked on the difference between the levels of the projected tides and the actual tides. In some cases they were off—higher or lower—by several inches. Robins asked, “If we can’t even predict the tides this week, how are we going to predict sea-level rise in the future?” This was, I realized, a twist on a familiar point of confusion (as well as a talking point for climate deniers), which is that if we can’t predict the weather next week, how can we predict the climate in twenty years? I pointed out to him that tides and sea level were very different: the daily tides were based on small and chaotic changes of winds and currents, while sea-level rise was about long-term averages. But Robins didn’t seem interested in such nuance. He just said, “Yeah, I understand,” and then changed the subject.

The second thing I learned was that Robins had a very clear plan for how Miami Beach was going to deal with sea-level rise, real or not.

“We’re going to raise the city two feet,” he told me, point-blank.

I was startled to hear this put so bluntly and so decisively. “What do you mean, you’re going to raise the city two feet?”

“I mean we’re going to raise all the streets and buildings in Miami Beach two feet. It might take some time, not going to happen overnight, but that is what we are going to do.”

“Do you have an engineering plan for this?”

“Not yet, but we’re working on it.”

“Do you have any idea what it will cost?”

“No, but we will figure out a way. There is a lot of money here.”

I pressed him for more details, but he offered none. So I was more than a little surprised a few months later when I heard Mayor Levine announce that the city planned to raise a few streets in Miami Beach. And the place they were going to start, naturally enough, was Sunset Harbour.

In the 1850s, Chicago was a booming outpost on the prairie, a city growing so fast that nobody gave much thought to prosaic things like urban planning or infrastructure. Wooden buildings gave way to five-story brick buildings, including big, fancy hotels. But as the population grew from 20,000 to more than 100,000 in just a decade, it became clear that chaotic build-whatever-you-want development couldn’t go on. The city’s buildings had been designed at various heights, so the wooden sidewalks were a jumble of stairs and planks, up and down and across mud holes that were, as a popular saying of the time goes, deep enough to drown a horse. Even worse, the city was built on a bog too near the shore of Lake Michigan—when it rained, it flooded. And because the newly built city had no municipal sewage system, those floodwaters were often contaminated. In 1854, a cholera epidemic killed 1,424 Chicagoans; between 1854 and 1860, dysentery killed 1,600.

To solve the flooding and sewage problems, city engineers came up with an innovative solution. Instead of digging in the muck to lay sewage pipes underground, they laid the sewage pipes on top of the ground and covered them by raising the entire city about eight feet. Ambitious engineers like George Pullman, who would later make his fortune with the invention of the Pullman railroad car, were soon using thousands of wooden corkscrew jacks to elevate five-story brick buildings without even cracking a pane of glass. Pullman’s most famous feat was elevating the Tremont House, the finest hotel in Chicago, which took up almost an entire city block, while the guests remained in the hotel. All in all, the raising of Chicago took about a decade, and it was a triumph of urban engineering. The contaminated bogs were eliminated, public health improved, and Chicago became one of the fastest-growing cities in the world.

But Miami Beach circa 2017 is not Chicago circa 1860. For one thing, Chicago was still a new city, with dirt roads and little infrastructure. Miami Beach has water lines, wires, sewage systems, paved roads, concrete sidewalks. Raising (or moving) a structure in old Chicago was relatively cheap compared to the cost of building anew. In Miami, in most cases, it’s the opposite.

Raising the Briggs House hotel with corkscrews in 1857. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia)

In Miami Beach, Mayor Levine and Mowry decided to get started anyway. Their strategy was to raise one street at a time, and to raise only the street and sidewalks. Then, over time, they hoped that owners of the buildings on the street would raise or rebuild the structures at a new, higher level.

By the end of 2016, about twenty blocks had been elevated, mostly in and around Sunset Harbour. The effect was surreal. The restaurants and shops were down at the old levels, but the streets and sidewalks two feet higher, so that to get to a restaurant, you had to step down into a sort of sunken patio. To get to the supermarket, which was originally built at a higher level, you had to step up. There were odd bumps in the road where the old elevations met the new. Beneath it all was a newly engineered pump and drainage system that was supposed to keep the low areas dry during big rains or king tides.

That was the idea, anyway. A few weeks before the king tides in 2016, Hurricane Matthew rolled up the East Coast. The storm didn’t target Miami directly, but the city was hit by torrential rains. As it happened, several of the new pumps in Sunset Harbour were offline. The neighborhood flooded with several feet of water, just like old times.

A few weeks later, during the king tides, there was water in the newly elevated neighborhood again—this time, the pumps were all working, but the king tides, combined with another big burst of rain, overwhelmed the system. One night, in the rain, I drove around Miami Beach and saw water not just in Sunset Harbour, but everywhere. It was car-wheel-deep in front of the Fontainebleau Hotel and around the Lincoln Road pedestrian mall (which also happened to be the priciest commercial real estate in the city) and lapping up against temporary flood barriers at a Florida Power & Light substation on Fortieth Street. The high water only lasted a few hours; it receded as the tides diminished. Although the reemergence of dry ground was reassuring, the flooding was terrifying to anyone who was paying close attention. It was nature’s preview of the disaster film to come.

At nine the next morning, just as the next cycle of king tides was about to hit, Henry Briceño, a geologist at Florida International University, picked me up in his well-worn silver Honda Civic. The trunk was full of ice chests and plastic bottles and scientific gear. Briceño, then seventy, who was born in Venezuela and worked there as a scientist until he was run out of the country by dictator Hugo Chávez, looked like he was on his way home from the hardware store, wearing a green polo shirt with a big water stain on it, khaki pants, and beat-up hiking shoes. He was a specialist in water quality, and by the time he picked me up, he had already been working for several hours, driving around to check on teams of grad students taking water samples across Miami Beach.

Shortly after we drove off, Briceño stopped at a traffic light and looked down at my shoes, which were low-cut sneakers. “I meant to remind you to bring along some rubber boots,” he said apologetically. “You won’t be wanting to get your feet wet.”

“I know—should have thought of that myself,” I said, feeling a little foolish.

“As long as you don’t have any cuts or open sores on your feet, it should be okay,” he said, although that did not exactly sound reassuring.

But I knew what he meant. He was going to be wading through waters that were likely to be polluted by human fecal bacteria, and if I wanted to come along, I should understand the risks.

And I did. Briceño’s work was important because it suggested a simple but often unacknowledged truth about sea-level rise: it ain’t gonna be pretty. In urban areas, the floods that pour into the city are not going to be luminous blue waters you’ll want to frolic in on your Jet Ski. They are going to be dark, smelly, and contaminated by organic and inorganic compounds, including, in some places, viruses and human shit.

Briceño’s interest in Miami Beach’s water quality began in 2013, when he saw neighbors wading through knee-deep water in the streets and thought, “Is that water safe?” He got out his instruments, did some testing, and found the water was definitely polluted. Not only were people walking through it, but it was also being pumped out into the fragile waters of Biscayne Bay. To better understand what was going on, Briceño organized a joint research project with scientists from FIU, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the University of Miami, and Nova Southeastern University. They sampled the water quality at a number of discharge sites over a period of four days during the king tides in 2014 and 2015. At four sites tested in 2015, every spot had fecal levels above state limits. Along Indian Creek Drive, a main thoroughfare in the city, levels were 622 times higher than limits allowed by the state. A storm drain outfall at Fourteenth Street measured 630 times higher than allowed.

When Briceño’s group presented their findings to the city in a report in 2015, city officials ignored it for nearly a year—until the Miami Herald got wind of it and published a story about Miami Beach’s polluted floodwaters in January 2016. Many powerful players in the Miami Beach business and political world were outraged that the Herald had published a story that could sully the city’s reputation as a vacation paradise. Mayor Levine accused the paper of running the story “in order to sell ads.” During a speech at a luncheon I attended celebrating the 100th anniversary of Miami Beach, Scott Robins said, “there is someone around here saying that we are dumping polluted water into the bay. That is not true… that is a lie… he is a liar.” (Later, I asked Briceño, who was in the room when Robins made his remarks, how he reacted: “I simply laughed quite loudly and said, ‘that son-of-a-bitch just called me a liar…!’ Then I stood up and left the venue.”) Beach commissioner Michael Grieco called his report a “hit job.” Mayor Levine went after Briceño personally at a city council meeting, suggesting that Briceño was trying to strong-arm the city into paying over $600,000 for a contract to test water. The Miami Beach city attorney wrote a letter to the Herald, demanding that they retract the article and charging that the article “recklessly and incorrectly depicts vile, unsafe water conditions around the city.” The Herald declined to retract the story.

Briceño, whose work is widely respected by his scientific colleagues, refused to be intimidated (this is a guy whose email signature includes a quote from physicist and science celebrity Neil deGrasse Tyson: “The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it”). “I don’t know what’s behind this mayor—I’m not attacking him personally,” Briceño told me as we drove through the city that morning. “I just want people to know that they shouldn’t be here swimming, because they are exposed. And he has been hiding this information. They are finally informing people. But they have known about it for a long time, and they have said nothing about it. Now, because of all the media attention these studies have received, they are being forced to acknowledge it.”

At about that time, we arrived at Briceño’s first sampling site, which was a few blocks from Sunset Harbour. We walked over to the seawall, where a couple of graduate students were dipping a plastic bottle into water that was rushing out of the outfall pipe. The water had a foul smell caused by hydrogen sulfide, a gas given off by decomposing organic material. Standing on the seawall, Briceño talked about how storm water—whether it’s from high tides or rainstorms or both—cycles through the system here, washing through the streets, seeping through the ground, and ending up in the storm water drainage pipes. Although the city has a municipal sewer system, many of the pipes—especially the smaller ones that connect homes and offices to the main sewer lines—are corroded or cracked. The sewage leaks out, mixes with the floodwater, and ends up either sitting in the streets or being pumped out into the bay. “But at the end of the day, what’s happening is not very complicated,” Briceño said. “There is a guy up there”—he pointed to some nearby apartments—“who is shitting, and it is coming out here.”

Briceño understands very well why some people don’t want to hear about any of this. “The entire tourist economy depends on the quality of water here,” he explained. “Tourists come here because they can swim and boat and Jet Ski. If the entire bay is smelling like this right now, I don’t think you’re going to want to go swim in there. So that’s what it is. The economy needs to be somehow protected. I understand that. But I also understand that because of sea-level rise, everyone here, sooner or later, is going to have to move away. In the meantime, we have to have the best standard of living we can, and best quality of water, for as long as we can. If we destroy that, nobody is going to come here, and we won’t have any money to raise the streets or build seawalls or do anything. So we have to keep our waters as clean as we can for as long as we can, and then use that time to plan how we are going to get the hell out of here.”

Next stop on our polluted water tour: Shorecrest, a poor neighborhood in Miami, just over the bridge from Miami Beach. We arrived just as the morning high tide was reaching its peak—the water in the street was three feet deep, reaching up into people’s yards, over their lawns, right up to their front doors. There were no traffic cones set up, no cops diverting traffic, no public health officials warning people to stay out of the water.

Briceño parked and began assembling his water sampling equipment and putting on his knee-high rubber boots. He noticed a guy with a camera about to stroll into the water. “I wouldn’t go in that water if I were you,” Briceño shouted. The guy nodded but walked into it anyway and started snapping photos.

While Briceño collected his water samples, I hopped and skipped over dry ground to a nearby apartment complex, where I found a woman named Maria Toubes staring at the incoming water from her second-floor doorstep. She was sixty-five and disabled, a hard life etched in her face. Inside, she had an eight-year-old niece whom she wouldn’t let out of the house because of the high waters. Toubes explained that she lived on a fixed income and had moved into this neighborhood a few months earlier because it allowed her to save $200 a month on rent.

As we talked, the water continued to rise, pushing up the street in front of her house and into her driveway. It felt like we were about to float away.

“Have you seen the water this high before?”

“Sometimes it comes up even higher,” she said.

“What do you do?”

She looked at me as if I had asked a very stupid question. “Stay inside,” she said.

“Has anyone from the city or state ever been here to warn you that the water may be polluted?”

She shook her head. “Nobody has been here to tell me anything.”

By the time we finished talking, the tide had risen even higher, and I was forced to wade through the floodwaters to get back to Briceño’s car. When I got there, I took off my shoes and socks, rinsed my feet with bottled water, then spent the rest of the morning barefoot. I watched Briceño process his water samples, filling up a syringe with water, then pushing the water through a filter, which catches all the impurities. He stored the water and the filter in a plastic cooler to preserve the bacteria (and anything else) until he got back to the lab.

A few weeks later, he emailed me results from the water samples at Shorecrest and around Miami Beach. The indicator that the EPA uses for fecal matter in the water is Enterococcus, which is a bacteria that is easily and reliably traceable. The EPA standard for acceptable contamination in water is 35 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters of water. According to Briceño’s tests, the floodwater in Shorecrest had 30,000 CFUs. Results for most of the sites he had sampled around Miami Beach were similarly high. To put it crudely, the water I was wading through, and that Maria Toubes and many others were living in, was full of shit.

In Miami-Dade County, the majority of homes and businesses are hooked up to a municipal sewer system, which collects waste through a network of underground pipes and sends it to a central sewage plant, where it is treated, then dumped into the ocean. In 2014, after more than 150 spills dumped more than 50 million gallons of sewage into Biscayne Bay, the county reached an agreement with the EPA to spend $1.6 billion on repairs; the county is now looking at injecting wastewater into a deep well 3,000 feet belowground. A larger problem, however, is that 20 percent of the people in Miami-Dade depend on old-fashioned backyard septic tanks. There are about 86,000 in-ground systems in Miami-Dade County, and a total of over 2 million in the state. And most of them are old and poorly maintained.

Septic tanks are basically just well-engineered holes in the ground. When you flush the toilet, wastewater drains into a concrete tank. Fecal matter and other wastes stay in the tank, decomposing into a sludge, while liquids run off into a leach field that surrounds the tank. When it’s working properly, the soil around the leach field acts as a filter, removing bacteria and pathogens. Septic tanks require regular maintenance: the sludge needs to be pumped out of the tanks, the leach fields checked to be sure they are not blocked or collapsed. But the State of Florida, like most state governments, requires no regular performance inspections of septic tanks. According to the Florida Department of Health, just 1 percent of the state’s systems are inspected and serviced each year. By one estimate, more than 40 percent of the septic tanks in the state aren’t functioning properly.

As sea levels rise and more and more neighborhoods are inundated, those problems are only going to get worse. “As the groundwater rises, the systems don’t drain properly,” Virginia Walsh, a senior geologist at the Miami-Dade Water and Sewer Department, explained to me. “Leach fields don’t filter out bacteria. A flooded septic system is worthless.” For Walsh and others concerned about water quality and public health in Miami as sea levels rise, septic tanks are a big problem. “We have seen it before in flooded areas,” Walsh told me. “The septic tanks pop right out of the ground. They begin to float.”

Brittinie Nesenman, the co-owner of Jason’s Septic Inc., one of the largest septic tank installers and service providers in Miami-Dade County, told me that leach fields need to be a foot above the water table to function properly; otherwise, the leach fields can collapse. “We are definitely getting more calls for repairs because water tables are rising,” Nesenman told me.

Erin Lipp, a microbiologist at the University of Georgia’s College of Public Health, participated in an experiment with septic tanks in the Florida Keys, where the water table is high. Residents in the Keys had noticed coral dying off, and increasing algae blooms. When researchers tested the waters in several canals, they found evidence of sewage pollution. It wasn’t hard to guess where it was coming from. Lipp and her colleagues put viral tracers in a toilet, flushed, and eleven hours later, the tracers showed up in a nearby canal. “And this in a place where everyone thought their septic tanks were working fine,” Lipp explained.

High levels of nutrients in leaking sewage cause algae blooms, which kill sea grass, which is vital to the ecosystem in places like Biscayne Bay. Some algae blooms are harmful to humans, such as blue-green algae, which is a liver and nerve toxin. Floridians got a vivid demonstration of this with Indian River in 2016, when one of the most diverse estuaries in the United States became a river of flocculent green glop that killed millions of fish and inspired YouTube videos of manatees being saved by Good Samaritans who turned on their hoses to douse them with freshwater. The Indian River glop was caused in part by excessive nutrients from agricultural runoff stored in Lake Okeechobee, but leaky septic systems along the river were also suspected as a prime cause.

The public health risks of drinking water polluted by human waste are well documented. In 2010, some 10,000 people in Haiti died and hundreds of thousands more were sickened by cholera, in an epidemic resulting from the mishandling of septic tanks at a UN Peacekeeper camp and dumping into a river. As late as the 1920s, before the advent of modern septic systems in the United States, typhoid was a fairly common disease.

But put aside drinking it—even swimming or bathing in contaminated water is risky. According to Erin Lipp, the chance of ingesting bacteria that cause diseases like cholera and typhoid is low, in part because even in soggy septic systems, the bacteria are big enough that they are trapped in the pores of the soil. The bigger risks are enteric viruses, most of which cause fevers, rashes, and diarrhea, but some of which are more serious, such as hepatitis A. And the risk doesn’t go away quickly. Enteric viruses can live for weeks in seawater.

The best fix for leaky in-ground septic tanks in a city like Miami is to get people hooked up to a municipal sewer system and then make sure the sewer system is well maintained. But that takes money—and planning. It costs about $15,000 for a homeowner to connect to a municipal sewer line—if one exists in the neighborhood. If it doesn’t, the county has to install a new line, which also costs a significant amount of money.

Leaky septic systems are not the only source of contamination urban residents need to be concerned about when their city starts to flood. In Miami, a 200-acre garbage dump known affectionately as Mount Trashmore sits right on the edge of Biscayne Bay. Since it opened in 1980, millions of tons of all the chemical-laden debris have been dumped there—fingernail polish, printer ink, oven cleaner, Freon, motor oil, degreaser, house paint, weed killer, fertilizers, rat poison. The disposal pit is sealed off by layers of clay at the bottom, but this stew of arsenic, chromium, copper, nickel, iron, lead, mercury, zinc, and benzene was never designed to be submerged.

In South Florida, not even the dead are safe from rising seas. Coffins are buoyant, and when water comes, they sometimes rise out of the ground. In other cases, water lifts the lids, allowing the remains to float out. This is not an uncommon event in flooded areas. In 2015, after a few days of extreme rainfall in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, dozens of coffins had to be recovered and reburied.

In Miami, many cemeteries are on low-lying ground that will be quickly inundated. Julia Tuttle, the founder of Miami, is one of the lucky ones. Miami City Cemetery, where she is buried, is 10 feet above sea level. On the other hand, 1950s comedian Jackie Gleason, who is interred at Our Lady of Mercy Cemetery, is entombed only 3.5 feet above sea level. Mount Nebo Miami Memorial Gardens, where gangster Meyer Lansky is laid to rest, is 4.5 feet above sea level. Actor Leslie Nielsen, who is interred at Evergreen Cemetery in Fort Lauderdale, is at 7 feet. Omar Mateen, the shooter who killed forty-nine people in a Florida nightclub in 2016, is buried in a Muslim cemetery that is just four feet above sea level. In the historic Key West Cemetery, about 60,000 people, including former slaves and Cuban freedom fighters, are buried less than eight feet above sea level.

A few days after my adventures with Briceño, I visited Bruce Mowry in his cluttered office on the third floor of Miami Beach City Hall. That morning, as usual, he was going in a thousand directions at once. “I don’t think I’ve put in less than a twelve-hour day since I’ve been here,” he boasted. He was living during the week at a small apartment in mid-beach, while his wife stayed at their permanent home 250 miles north near Daytona Beach (he visited on weekends). With a staff of twelve engineers, it was Mowry’s job to keep the city from drowning—and, equally important, to keep people from thinking the city was drowning.

Mowry is not a visionary. He is a tactician. He is the guy who designs the plan to get the troops up the beach on D-day. “Basically people don’t like me because they feel like I intimidate them, but I tell them, ‘Hey, I’m here for one reason.’ As I told the city manager when I came here, ‘I’m here to build as many projects as I can before I die.’ Some people say, ‘That’s not a real good attitude.’ And I say, ‘That’s the way I operate. I build projects.’”

Here are some of the projects that were on Mowry’s to-do list the day we talked: To solve the problem of bacteria in water being discharged into the bay, he was looking at a system that would treat all discharges with ultraviolet light, which would kill bacteria or viruses (this would solve the problem of contamination in the bay but would do nothing to help with leakage from in-ground septic systems, which was the cause of the contamination I saw in Shorecrest, which is not part of Miami Beach). To measure rising groundwater beneath the city, he was drilling forty-two observation wells. To better monitor local sea levels, he was installing two new tide gauges in different parts of the city. He was overseeing the installation of a half dozen new, bigger pumps (Mowry says the city’s master plan calls for a total of sixty pumps in low-lying areas; by early 2017, about thirty were installed and operational). He was arguing with historic preservationists about building code requirements in historic neighborhoods. He was talking with other city officials about mandating higher first-floor ceilings, so that as seas rose in the future, the bottom floors of buildings could be raised and there would still be enough headroom on the first floors. He was engaging design firms to figure out clever ways to hide diesel generators for the pumps (people complain that the generators are too ugly and too noisy). His highest-profile project was overseeing a $25-million venture with the state to raise Indian Creek Drive, a key thoroughfare on the bay side of the island, as well as to build a new seawall and install yet another pump station at the same location.

The ultimate goal of all of this, in Mowry’s view, was to buy time. “I look at sea-level rise as basically an opportunity to start upgrading our infrastructure, but do it in a commonsense manner. When a road needs to be replaced, go in and replace it—but raise it higher while you’re at it. I think by triggering certain things like that, you create a domino effect. In the next thirty to fifty years, this city is going to get higher and higher. Buildings that are cost-effective to raise will eventually be raised. Buildings that aren’t will be demolished and something new will be built.”

But Mowry understands the need to move fast. “The problem is that we have the economic engine here, and we have to get moving before the economy crashes on this city because of not doing anything. We need to get started now, while we have the revenues to do it. You don’t wait until water starts pumping out of the ground and say, ‘Oh, I guess we need to start looking at groundwater issues.’”

Mowry also understands that engineers are not gods, and that engineering has its limits. What will allow Miami to thrive in the future is not simply the fact that it’s not underwater. It will thrive if it is a lively, creative, thriving, safe, and equitable city—and one that also happens not to be underwater.

“From my point of view, there’s nothing that I can’t overcome,” Mowry said. “But I am not the only one here. This is a city. I only play a function as technical advisor, telling civic leaders what I can do and what we can do. But if residents don’t agree, if the businesses don’t agree, and the visitors coming to this city don’t agree, then the economy of the city dies and the engineer’s unemployed. In other words, just because I can tell you how to solve the problem, if it doesn’t fit within the culture of this city and the future of this city, then it’s not the right solution.”

What exactly the Miami of the future will look like is a subject of constant discussion among those who understand the risks the city faces. A few weeks earlier, I had attended an evening talk in downtown Miami at the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects, which is headed by architect Reinaldo Borges. At the talk, landscape architects Walter Meyer and Jennifer Bolstad of Local Office Landscape Architecture outlined a plan to reshape a Miami neighborhood that was, in the context of Florida’s pave-the-swamp development mentality, both subtle and subversive. Meyer and Bolstad called their approach “forensic ecology.” Like the innovative proposals by Susannah Drake and Kate Orff to protect New York City that I mentioned in an earlier chapter, Meyer and Bolstad aimed to work with nature, not against it. As an example, they showed plans for the redevelopment of Arch Creek Basin in north Miami, where they proposed tearing down houses that had been built in a low-lying neighborhood that had been a natural slough, connecting the Everglades to the sea, and building new housing on higher ground. “The idea is to reduce risk by relocating people, but doing it locally, so that families and neighborhoods are not disrupted,” Meyer said. The natural slough would be restored, allowing water to collect and drain along the natural contours of the land. This was not a long-term solution to sea-level rise for the neighborhood, but it would buy time and encourage city planners to think about the natural landscape as something more than just a pile of dirt to be bulldozed and paved over.

After the event, I walked out with Borges, and we sat for several hours in his Range Rover Sport in the parking lot, talking. (Borges says his Range Rover is the perfect car for Miami: “It can roll through four feet of water, no problem.”) During the course of reporting this book, I spent many hours with Borges and found him to be deeply thoughtful on the issue of sea-level rise. As an architect, he understands the imperative to keep the economic engine of Miami humming. As a father of two daughters, he also understands the need to push city officials to prepare Miami for a watery future. He has spent hours in meetings, arguing for better building codes and pointing out the insanity of building condo towers with underground parking lots. But he also understands the draw of living by the ocean (Borges himself lives on the twenty-fifth floor of a condo tower in downtown Miami). “People love water,” he told me. “They love the sense of peace it gives them, the restfulness. If I could build a building that could just hover over the water, people would love it.”

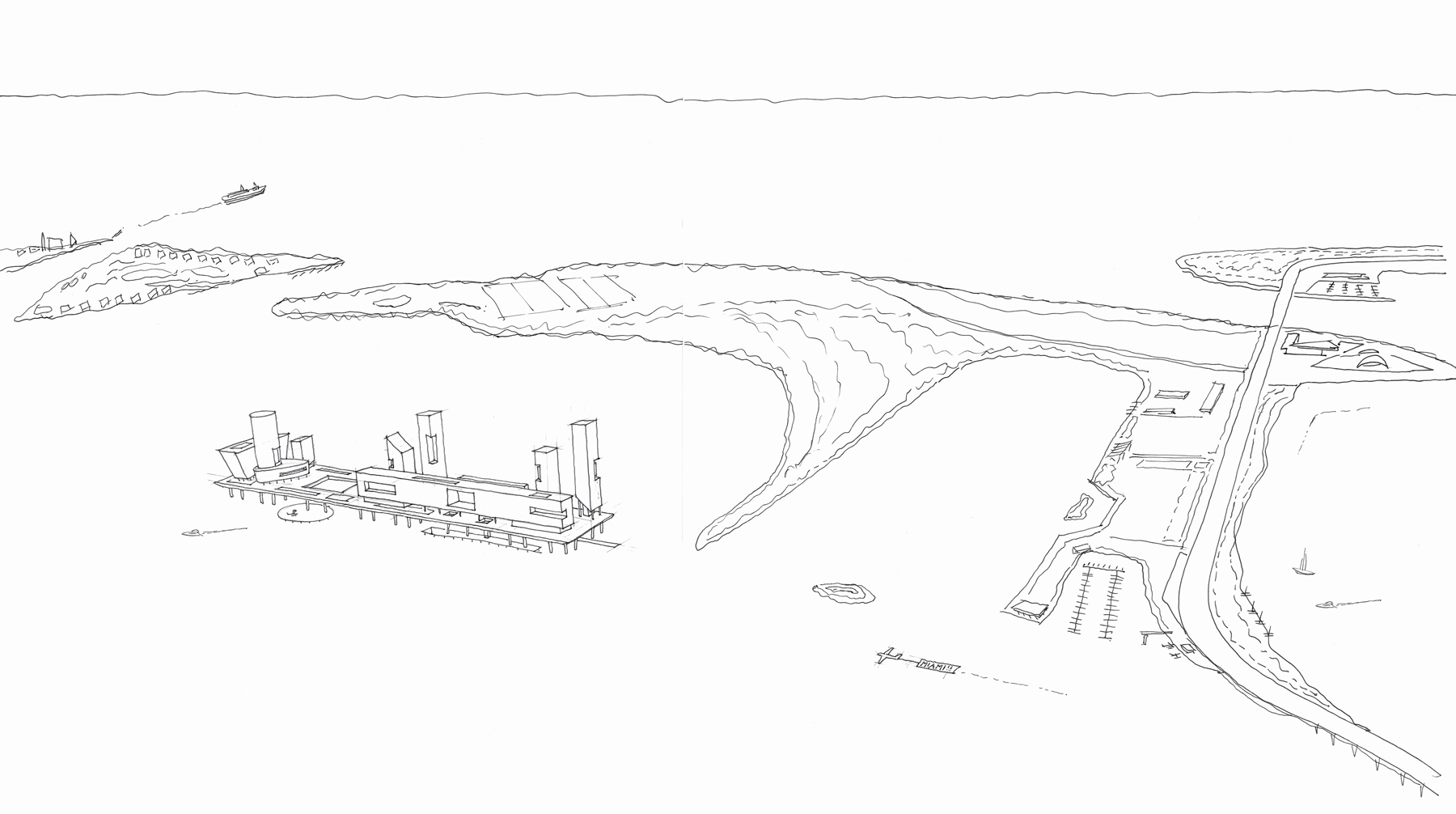

Borges views sea-level rise as a creative challenge, and one that is only limited by our own imaginations. Or as Harvard philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger put it: “At every level the greatest obstacle to transforming the world is that we lack the clarity and imagination to conceive that it could be different.” Borges is enamored of Japanese architect Kiyonori Kikutake, who worked out elaborate plans for floating cities in Tokyo Bay in the 1950s. In his spare time, Borges had been sketching out his own ideas, including building water-view condos on both sides of the bridge to Virginia Key, a notion inspired by the Ponte Vecchio, the famous medieval bridge in Florence. Another idea, which occurred to him when he saw a picture of an oil rig, was to construct a series of platforms in Biscayne Bay, elevated seventy-five feet or so above the water on heavy pilings, each holding high-rise towers for thousands of people and accessible by water ferries. “Why can’t we do something like that?” Borges said that night as we sat in the dark parking lot. “Yes, we have a lot of problems, and yes, it will require some radical thinking. But I think this is an exciting time. One of the great strengths of Miami is that it’s still a new city, still growing, still forming its identity. There is so much energy and money and creativity here. We just need to put it to work in a new way.”

Sketch of Reinaldo Borges’ platform city in Miami’s Biscayne Bay. (Illustration courtesy of Reinaldo Borges)

In Miami, as in every other city in the world, there is hope that if sea levels rise slowly enough, it will erode the politics of denial and inspire innovation and creative thinking, and the whole crisis will be manageable. People who don’t want to live with the risk of higher water can move to Denver, while the people who want to experiment with a platform city and new ways of living with water can remain behind, pioneers in a watery urban renewal.

The problem is, rising seas also raise other kinds of risks—including the risk of sudden catastrophe. In Miami, the biggest concern is a potential nuclear disaster at the Turkey Point nuclear power plant, which sits on the edge of Biscayne Bay just south of Miami, completely exposed to hurricanes and rising seas. “It is impossible to imagine a stupider place to build a nuclear plant than Turkey Point,” said Philip Stoddard, the mayor of South Miami and an outspoken critic of the plant.

The Turkey Point nukes began operation in the early 1970s, long before sea-level rise was a well-recognized risk. But precautions were taken to protect the plant from hurricanes; most important, the reactor vessels are elevated twenty feet above sea level, several feet above the maximum storm surge the region has seen. According to Florida Power & Light, the electric utility that operates the plants, there is virtually no chance of a storm surge causing problems with the reactors. As evidence of this, Michael Waldron, a spokesman for the company, points to the fact that Hurricane Andrew, a Category 5 hurricane, passed directly over the plant in 1992, with very little damage. “It goes without saying that safety is our number-one priority,” Waldron said in an email.

“It is impossible to imagine a stupider place to build a nuclear plant than Turkey Point,” says Philip Stoddard, the mayor of South Miami. (Photo courtesy of Shutterstock)

But Stoddard and other critics of the plant are not reassured. For one thing, although the plant did weather the hurricane, the peak storm surge, which was seventeen feet high, passed ten miles north of the plant. According to the late Peter Harlem, who was a noted research geologist at Florida International University, the plant itself only weathered a surge of about three feet—hardly a testament to the storm-readiness of the plant. How would Turkey Point fare if it was hit with a Hurricane Katrina–size storm surge of twenty-eight feet?

Stoddard also pointed out that although the reactors themselves are elevated, some of the other equipment is not. “I was given a tour of the plant in 2011,” he said. “It was impressively lashed down against wind, but even I could see vulnerabilities to water.” Stoddard noticed that some of the ancillary equipment was not raised high enough. He was particularly struck by the location of one of the emergency diesel generators, which are crucial for keeping cooling waters circulating in the event of a power failure (it was the failure of four layers of power supply that caused the meltdown of reactors in Fukushima, Japan, after the plant was hit by a tsunami in 2011). Stoddard said the generator was located about fifteen feet above sea level, and it was housed in a container with open louvers. “How easy would it be for water to flow into that? How well does that generator work when it is under water?”

Another problem: Turkey Point uses a system of cooling canals to dissipate heat. Those canals are cut into coastal marsh surrounding the plant, which is only about two feet above sea level. Besides being vulnerable to storm surges, the cooling canals are also polluting the bay. In 2014, regulators discovered that the leaky canals were pushing an underground plume of salt water miles inland, threatening drinking water supplies, and leaking water tainted with tritium, a radioactive element, into the fragile waters of the Biscayne National Park.

But the biggest problem of all is that inundation maps show that with just one foot of sea-level rise, the cooling ponds begin to flood, with two feet of rise, they are inundated, three feet of rise, and Turkey Point is cut off from the mainland and accessible only by boat or aircraft. And the higher the seas go, the deeper it’s submerged.

According to Dave Lochbaum, a nuclear engineer and the director of the Nuclear Safety Project for the Union of Concerned Scientists, the situation at Turkey Point underscores the backwardness of how we calculate the risks of nuclear power. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which oversees the safety of nukes in America, demands that operators take into account past natural hazards such as storms and earthquakes, “but they are silent about future hazards like sea-level rise and increasing storm surges,” Lochbaum said. The task force that examined nuclear safety regulations after the Fukushima tsunami recommended that the NRC begin taking future events into account, but so far, the commission has not acted on the recommendation.

Still, Florida Power & Light insists the plant is perfectly safe. When I asked for details about FPL’s plans to armor the plant against sea-level rise, its PR reps were elusive. They told me the plant’s current design is suitable to handle sea-level rise but would not tell me how much. (Six inches? Six feet?) They would not disclose plans to protect or redesign the cooling canals. They assured me that “all equipment and components vital to nuclear safety are flood-protected to twenty-two feet above sea level.” But when I asked to visit the plant and see for myself, they refused.

I went out there anyway. I was denied access to the inner workings, but I got a very nice view of two forty-year-old reactors perched on the edge of a rising sea with millions of people living within a few miles of the plant. It was as clear a picture of the insanity of modern life as I’ve ever seen.

Florida Power & Light thinks Turkey Point is such a great place for nukes that it has proposed a $20-billion plan to build two more reactors out there. Given the life expectancy of a nuke plant, it means that the people of South Florida would likely live with the threat of a radioactive cloud over their heads until at least 2085. In late 2016, after a seven-year environmental review, federal regulators approved the plan, stating that the two new reactors would have virtually no impact on the environment. The report said nothing about sea-level rise.