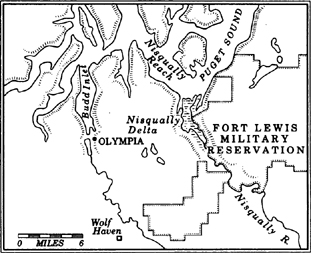

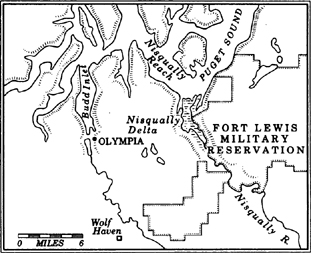

At the Nisqually Delta, where Puget Sound picks up the runoff from one of Mount Rainier’s longest glaciers and then doglegs north, creatures of the air and water have hunkered down for their last stand. It’s an odd place for a sanctuary, this intersection of man and aqua-beast, of freeway and marsh, of fresh water and salt. At the time of Winthrop’s visit, the mouth of the Nisqually served as regional headquarters for the otter- and beaver-hide trade; it was a swap mart for hard-edged men carrying furs to be worn by soft-edged urbanites in distant cities. The fashion designer stood atop the predator chain then.

I come to the Nisqually Delta, not by canoe as did Winthrop, but on an interstate that carries eight lanes of traffic through eighty miles of megalopolis. As the road drops to cross the delta, leaving behind acres of inflatable exurbs and Chuck E. Cheese pizza palaces, the land turns shaggy and damp, a sudden reappearance of the original form. What used to be the fortress of man, surrounded by wild, has become the fortress of beast, surrounded by city. I find a handful of Nisqually Indians holding to a slice of land along the river, and soldiers playing golf on a bluff once guarded by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The mosaic of salt water and river rush—one of the last true wetlands left on the West Coast—now is a federal wildlife refuge, the animal equivalant of the Indian reservation. Hunters pick off returning loons as they near the Nisqually, but once the birds make it through the firing line to land on the fingers of the river, they find a smorgasbord of food, and federal government protection. The refuge designation came just in time: the Weyerhaeuser Company, owner of 1.7 million acres of timberland in Washington, wanted to build a log-export facility in the Nisqually Delta to help speed the shipment of fresh-cut trees to Japan. When the company backed off during the timber recession of the mid-1980s, conservationists stepped in and saved the delta. However, it may turn out to be wildlife under glass; the county surrounding the delta is the fastest-growing community in the country outside of Florida, and Weyerhaeuser, which calls itself the tree-growing company, plans to build a new city of fourteen thousand people on its acreage bordering the refuge.

A sponge for winter rains, and feasting grounds for species that thrive in the blend of mud and grass, the wetlands in this wet land have always been looked upon as ill-defined and malformed. Not suitable for human habitation, they were judged to be worthless. One by one, the estuaries of the West Coast have been filled in, paved over, planked up. Puget Sound, with more than two thousand miles of inland shoreline, has only a few small places left where river and soil and tide converge to support the bounty of delta life. The Snohomish, outside Everett, has lost three-fourths of its marsh; the Duwamish marsh has disappeared altogether, its tideland filled in with 12 million cubic yards to accommodate Seattle’s early-century expansion. Commencement Bay, where the Puyallup has lost all but a few acres of its wetland cushion, is a toxic nightmare, home of the three-eyed fish and a pulp mill which has been the source of one of the most lasting nicknames in the Northwest—the Aroma of Tacoma. For the last century, oxygen-starved marine life in Commencement Bay has been fed a diet of heavy metals, PCBs and algae.

The Nisqually, for the time being, looks as it did when Winthrop saw it: wide and wet, a stew of shorebirds and marine mammals, more than 240 animal species, with tall grass growing around scattered firs, thick cottonwoods along the river, and in early summer, waves of pink blossoms from the thorny blackberry bushes. I could set up camp here, as the Nisquallies have for centuries, as Winthrop did overnight, and never need to walk more than a few miles to find every food source necessary to lead a long life. But I don’t need the delta for food.

Walking a trail planked over the mud and eelgrass on a warm summer morning, a day when much of the country is praying for water and trembling about the prospect of global warming, I pass through a window to the air-conditioned wild; with each step, traffic noise gradually recedes and the full-throated sounds of marsh creatures gain. Inside this thousand-acre garrison eagles nest atop box springs of heavy twigs, mallards feast, needle-legged blue herons and big-headed belted kingfishers dive for prey, and assorted others of webbed toe and water-resistant coat hide out for a few weeks. But where are the sea otters? Winthrop found stacks of their furs inside the palisade of Fort Nisqually here. Where are the packs of wolves that howled outside the gates and disrupted his sleep? Where are the whales he dodged while paddling down the length of Puget Sound? Where are the geoducks he called “large, queer clams,” century-old bivalves with necks half as long as a jumprope?

To find a sea otter in the Northwest in the last years of the twentieth century, you go to the Seattle Aquarium, where a trained mammal does tricks for tourists. Otherwise, the animal that brought white men to this corner of the world has largely disappeared—officially extinct off the Washington, Oregon and British Columbian coasts for nearly half a century. A few transplants introduced under the protection of federal laws have since been placed in Northwestern waters, but their fate is uncertain. A recent spill from a barge carrying heavy bunker oil killed several of them; with their fur soiled, sea otters lose their coat of warmth and die a painful death from hypothermia. Otter Crest, on the Oregon coast, has no such creatures swimming near its beach. Nootka Sound, where Captain Cook first noted the easy-kill, big-money mammal, has no descendants from that era playing in its waters.

Sea otters have never caused great fear or awe. They backstroke through cold channels looking for new places to make water slides. They plunge to great depths, seeing how long they can hold their breath. They sing to their young, which gave rise to the myth of the mermaid; horny sailors, hearing the distant song of a sea otter mother to her pup, imagined a large-breasted amphibian calling them to shore. Few things are funnier to one otter than sneaking up on another otter and biting the mate’s tiny ear. They never migrate, food is easy, the water’s always fine.

To be a comedian in nature is to have a short life. While the pursuit of spice and the cultivation of tobacco may have led to early colonization of the eastern part of North America, it was this mammal, among the most docile in all of nature, that was responsible for bringing the hordes of Boston and King George men to the Pacific Northwest. Once otter pelts replaced the nonexistent Northwest Passage as the only justification for sailing eight months around Cape Horn and up the Pacific Coast, it took less than half a century to kill most of them. By the 1820s, up to 500,000 otters had been caught and stripped of their thick, luxuriant hide. Thus began a pattern: as long as this land brought wealth to those who stepped ashore, it was prized. Winthrop, and others who said the lasting value of the Northwest was not extractive, were lonely voices until the time came when there was very little left to take.

Peter Pans at heart, sea otters shy away from early attachment; when at last they do breed, the females seldom produce more than a single pup. A standard ploy during the early nineteenth century was to snatch the baby, thus luring the mother out, who was then clubbed. The orphan, more often than not, died without the mother’s milk or drowned without the benefit of maternal swimming lessons, accelerating the decline of the species. But through it all the otters kept on their backs, balancing clams on their noses, playing pinch with Dungeness crabs. A large sea otter pelt, in perfect condition, could fetch as much as two thousand dollars in London during the early nineteenth century. Such money—one pelt could bring the equivalent of five years of wages and a stake in the bank—was earned from the simple task of slamming the skull of a smiling eighty-pound mammal. By the early 1820s the Hudson’s Bay Company was calling for conservation measures. Their network of trading posts, so English and orderly, so profitable and legally monopolistic, was in danger of losing its chief source of income. But by then it was too late.

Asked to assess the value of all land north of the Columbia River before the United States and England settled their boundary dispute, an American government expert wrote that “The country north and west of the Columbia, extending north to the 49th degree of latitude and west to the sea, is extremely worthless.” A marsh, thick with marine life, had no value. A mountain range with glaciers and streams and spires enough to fill an area twice the size of the Swiss Alps, was dispensable. A dozen rivers, each carrying enough salmon in a single run to feed every native and every Boston man in the new country at a single sitting, was a trifle. The great problem with the area north of the Columbia was, as the American wrote, “There are hardly any furs.” Having depleted the Northwest of the first resource to be exploited here, the Boston men were already pronouncing it worthless.

Young Teddy Winthrop and three Clallam Indians arrived at the Nisqually Delta on a hot day in late August of 1853. Seattle, fifty miles to the north, was a mudflat with a handful of timber beasts and a waterfront whorehouse. Olympia, one inlet west of the delta, housed a few rotting territorial-government structures. But the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Nisqually, situated on land that had recently become American territory, exuded an air of permanence and authority. When Winthrop pulled up his canoe at the river’s mouth and hiked inland to Fort Nisqually, the company was already turning to agriculture, growing strawberries, gooseberries, carrots, potatoes and other vegetables in such quantities that they kept the other forts supplied with food and sold the surplus to the Russians in Alaska. Winthrop, gazing up at the twilight-pink flank of Rainier behind the ten-foot-high walls of the fort, found the setting enchanting. He wanted to get closer to this “giant mountain dome of snow swelling and seeming to fill the aerial spheres.” The Nisqually Glacier, one of the longest tongues of ice on the mountain and the river’s headwaters, gleamed in late sunlight. A climate barometer, the glacier has shrunk by more than a mile since then.

The fort was full of the commerce of dead-animal dealings.

Winthrop wrote: “Rusty Indians, in all degrees of froziness [sic] of person and costume, were trading at the shop for the three b’s of Indian desire—blankets, beads, and ’baccy—representatives of need, vanity and luxury.” He noted a great quantity of “otter, beaver and skunk skins and similar treasures.” Winthrop again enjoyed the civil company, imported wines and fine china of the Gentlemen running the company post. He obtained two horses for the trip across the mountains, another guide, this a Klickitat Indian from east of the Cascades, more hardtack and pork, some roots. The shopping spree cost him thirty dollars. Bedding down inside the fort at night, he heard the howl of timber wolves. Lucky man. The true call of the wild has not been heard in this part of the world for some time. The poison campaign which killed upwards of two million wolves in less than fifty years was already underway in the midnineteenth century. Even the Gentlemen of the Hudson’s Bay post at the Nisqually Delta, who showed some conservationist leanings despite the nature of their business, took up one of the favorite weapons of the frontier—strychnine—against the wolves that attacked their livestock.

To find a wolf in the Northwest in the last years of the twentieth century, you must go above the Nisqually Delta to the bluff and travel south for about thirty miles until you reach a somewhat spooky warren of orange-eyed carnivores—Wolf Haven, it’s called. The Gray Wolf Valley on the Olympic Peninsula has no such creatures. Bounty hunters killed off the last wolves in the state fifty years ago in that valley, which is one big reason why helicopters are chasing goats in the Olympics this summer, trying to thin a herd that no longer has a predator.

At Wolf Haven, everybody has a beard. People who stay together long enough are supposed to start looking alike; a similar trend is evident at Wolf Haven, where peacocks perch from the misted branches of spruce trees, and the evening air is filled with the jabbering of humans trying to communicate with three dozen wolves. Two volunteers proudly show me their bite marks. One of them says, “There is no better feeling in the world than French-kissing a wolf.”

On summer nights when the sky is clear and the great black Out There is full of mystery, cars drive along the old Hudson’s Bay Company fur-trading trail, turn off into the woods and pull up at Wolf Haven. Here, the people take pictures and then gather around a big bonfire and howl. A whole gaggle of captive wolves howls back. And then the Wolf Haven leaders try to get everybody to howl together. A “howl-in,” they call it. It’s all part of the job of trying to remake the image of one of the most maligned creatures in history.

I walk among the wolves with their benefactor, a chain-smoking thirty-six-year-old man named Stephen Kuntz. He has a beard, a bit of a beer gut, a baseball hat with a wolf emblem on the front. His van carries a personalized license plate—WOLF 1. He stops to chat with Windsong, a female buffalo wolf who spends a lot of time on the rubber-chicken circuit, appearing before Rotary Clubs, at county fairs, in an occasional spot on the Today show. Nearby is a timber wolf named Rogue, retrieved from the garbage dumps of Portland, now learning to howl for the first time. The star of this sixty-acre spread is a white arctic wolf named Lucan. This ghost-colored carnivore was once an habitué of a rich man’s private zoo; upon his death, the owner left Lucan with Wolf Haven.

Steve Kuntz has spent the last thirteen years of his life living with wolves; on the whole, they make better companions than humans, he says. His chief assistant, an earnest, bearded biologist named Jack Laufer, goes even further: “For me it’s easier to talk with these wolves than it is to talk with people,” he says. “They’re a lot more open and honest with their feelings.”

They share their feelings with you?

“When they howl, it’s vocalization, it conveys plenty. I can’t think of anything important that I can say which they can’t say.” Laufer speaks a few lines in English to Lucan, who says nothing. “What’s more,” he says, “wolves are a lot more compassionate than most humans. The pack—the community—is the most important thing to them. The pack always works together. They are monogamous. They breed for life. And they’re faithful. You won’t see a sadder thing than a wolf who’s lost a mate.”

The two Wolf Haven leaders go through the numbers: wolves used to inhabit all of North America above the 30th Parallel, but now they’ve disappeared in every state but four; wolves were not only poisoned and gunned for bounty, they were set on fire; during the height of the cattlemen’s poison campaign, a thousand wolves a day were killed; Oregon does not have a single wild wolf; Idaho has six, and Washington has zero. I correct them: Last summer, while exploring a meadow near the moraine of the Carbon Glacier on Mount Rainier’s north side, I looked across the flower fields and saw a gray timber wolf, Canis lupus. His tongue out, tail down, the wolf strode across the meadow, moving at a fast clip. I snapped a picture, backpedaled, then headed for higher ground. Like everyone, I grew up with the myth of the man-eating wolf, the lecher with bad breath, a devil in disguise.

The image problem, I think, has to do with the wolf’s appetite. There is no getting around their love of fresh, raw meat; after a kill, usually carried out by a pack closing in on a lame animal, a single wolf can eat up to a fourth of its body weight. They sometimes kill more than they can eat. The sight of eight wolves bringing down a deer—nipping at the thighs, then going for the jugular—is blood-spurting violence of the type seldom discussed at Audubon Society meetings. The Indians, for the most part, were not afraid of wolves and attributed spiritual qualities to them. Lewis and Clark ate wolves during the lean days of their cross-country expedition. It wasn’t until the wagon trains came west with livestock in the 1840s and ’50s—presenting an easy meal for the wolf packs—that Canis lupus became the homesteader’s worst enemy. In some counties of the West, it was against the law not to put poison on the fence post. Yet, as Kuntz and other neo-wolf lovers point out, there is not a single documented case of a healthy wolf ever attacking a human.

“Of course, I’ve been bit a couple times—feels like somebody smacked you on the hand with a hammer—but that was from playing around,” says Kuntz.

Wolves still are hunted in British Columbia, often from helicopters by sportsmen who’ve paid up to $15,000 in a lottery. The provincial government says the aerial hunts are necessary because too many moose, caribou and mountain sheep are being killed by the wolf packs of British Columbia, whose numbers may be as high as five thousand. Some biologists accuse the government of hiding their true intentions; they say the game managers who approve the wolf kill want to build up the herds of trophy animals in British Columbia, where hunting is big business. During Expo ’86, the wolf kills were stopped; 20 million people visited Vancouver with nary a peep heard about the helicopter hunting. In the years since, however, the kills have resumed.

Much of the change in attitude has come about because of people like Steve Kuntz, who calls his captive wolves “ambassadors for their lost brothers in the wild.” A native of Trenton, New Jersey, he was the kind of kid who put a frog in his pocket and then kept it in his room until his mom forced him to get rid of it. He once had a snapping turtle for a pet, but preferred big dogs like German shepherds. On his own at age thirteen, he never finished high school, moved all over the Northeast, and then to the Southwest, where he lived for a while in a hippie commune. Working a construction job in Colorado, he saw an ad in the paper offering a stray wolf pup for sale. He took the pup home, named it Blackfoot, and became quite attached. It was a buffalo wolf, one of the descendants of the great packs that used to attack bison on the plains east of the Rocky Mountains. Kuntz treated Blackfoot like a dog, keeping it on a leash, taking it for walks. But something was wrong.

In Washington with his wife, Linda, and Blackfoot, Kuntz looked up a man, Ed Andrews, who kept several wolves on his property. Andrews was having a hard time holding on to the property and the wolves at the same time, so he turned his pack over to Kuntz. Reluctant at first, Kuntz and his wife soon took on the manners and attitude of orphanage owners—bring us your stray wolves, your zoo rejects, your urban misfits. The early years of Wolf Haven were lean, but then they started the howl-ins. In an age of theme parks, the idea of sitting around a bonfire under spruce trees with a bunch of wolves and howling at the moon has terrific appeal. Tourists come by the carloads, entering the grounds as curious, usually neutral visitors and leaving as true believers, heads full of the new gospel of the wolf. The wolves inside the mesh-wired compound are their own best pitchmen. They play tag. They kiss each other. They bite each other’s ears.

Before coming to Wolf Haven, I read a book by Barry Lopez, Of Wolves and Men. Devoid of sentiment, Lopez makes a good case for the wolf, decrying the national tragedy of our annihilation of this animal in the wild, stripping away the myths. But he brings up something that comes to mind now as I walk among Lucan and Rogue and Windsong, the half-moon overhead dipping in and out of the stretch clouds. “I do not wish to encourage people to raise wolves,” Lopez wrote. “Wolves don’t belong living with people.” I want to ask Kuntz about this. He’s howling away with the arctic wolf, a beautiful creature with its thick, pure-white coat; the animal seems like a spirit at play, jumping and yelping with Kuntz. I decide to let them howl, uninterrupted; such is the best language at Wolf Haven.

Coastal Indian legend has it that the killer whale is a wolf that was stranded at sea. Like wolves, Orcinus orca are the top of the predator chain, are very smart, and travel in packs. Their sense of family would put a Mormon patriarch to shame; the offspring spend their entire life within their mother’s pod, a traveling unit of up to twenty whales. One pod of killer whales in Puget Sound includes an eighty-three-year-old grandmother; slow-moving and revered, she is the keeper of family secrets and tips on how best to ambush a harbor seal. Orcas don’t howl, but they communicate in dialects unique to each region. They use sonar to hunt and are capable of distinguishing one small species of fish from another at a distance of three hundred yards. After a few days’ absence, returning whales greet their pod mates with a showy ceremony. There is no documented case of an orca killing a human. But until a few years ago, they were considered black-and-white villains.

To find an orca in the Northwest in the last few years of the twentieth century, you must get in a boat and go to the deep, clean waters around the San Juan Islands, a place of great hope for those who believe humans can get along with other creatures without clubbing or caging them. Whaletown on Vancouver Island has no such mammals off its coast; it’s a shell of a shore town, condemned to die by previous avarice. Blubber Bay, similarly named by the nineteenth-century men from Nantucket and New Bedford, is devoid of the animal oil that used to light the world’s lamps in the days before electricity. The blue whale, largest creature ever to inhabit the earth, has disappeared completely from Washington coastal waters and Puget Sound. For thousands of years, the Makah Indians chased various whales, looking for thirty-foot-high spouts in raging surf off the northwestern tip of Washington. They threw harpoons attached to sealskin floats at the flanks of the big creatures. Finally, exhausted after days of chase, the whales would be towed to the beach. The Makahs have not hunted any type of whale since 1913. The efficient whaling factory ships of the 1920s eliminated the blue whale from Northwestern waters. And you won’t find a killer whale at the aquarium in Seattle, which was one of the first places in the country to put this twenty-five-foot mammal on display, inside a small cement tank. Prodded by a change in public attitude, the state of Washington has since outlawed the capture and containment of orcas, the only animal with a brain physiology comparable to that of humans.

The current in Haro Strait is so swift during the twice-a-day tidal shift that it produces whitecaps which look like Colorado River rapids. Three pods of killer whales live year-round in Puget Sound, and once every few days most of them pass by Haro Strait, shared by the United States and Canada. From a whale’s point of view, it’s a great fish-funneling spot; in late summer, sockeye salmon come in from the ocean up the Strait of Juan de Fuca and pass this point on their way to spawning grounds in the Fraser River. The whales find the schools and open their mouths, straining out lesser edibles.

Whale-watching requires the patience of a gardener in winter. I’m in a small boat, trying to hold the binoculars with one hand and the guard rail with the other as I scan the water around the northern San Juan Islands. The day is bright, as they almost always are during the warm months in this archipelago. People who come to the San Juans, no matter their background or degree of sensitivity to the earth, invariably fall in love with the natural world; in turn, the natural world repays such affection. Man is but one resident, in places a fairly insignificant one, in the habitat of the San Juans. The islands are fir-covered mountains with all but the summits buried by sea. Just offshore, the water is a thousand feet deep in parts; year-round, it stays at a temperature of forty-six degrees Fahrenheit. As species continue to die out in most other places of the world, the San Juans belong to creatures on the comeback—killer whales, harbor seals, bald eagles. Eighty-four islands in the San Juan chain are wildlife refuges; of those, humans are allowed to visit only three.

We stop for a while to watch harbor seals. About six feet long, they sprawl atop rocks close to water, soaking in sun. As we approach, their personality quirks reveal themselves. Their heads are like those of fashion models—sleek and clean, with slicked-back hair. They have front-end flippers, and no external ears. For years, the harbor seal was considered an enemy; the state of Washington paid a five-dollar bounty for any seal snout brought into a game office. Hunters would motor to within a few yards of their targets, then shoot the seals from the boat. Between 1946 and 1960, about seventeen thousand harbor seals were killed this way. Now, they are protected by federal law. However, they do have a predator.

We move on, out toward Canadian water, passing Spieden Island—a grassy, open isle with large madrona trees latched onto bits of hardened soil in the rock outcrops. In the 1970s, a group of investors purchased the island and imported to it a variety of exotic animals. They intended to have a sort of safari theme park here, a place where hunters with no sense of sport and deep pockets could sit on stools and shoot transplanted exotic animals who had little room to roam and no room to hide. When residents of other San Juan Islands found out about this, they orchestrated a publicity campaign that, at its peak, brought the crew from 60 Minutes to tiny, uninhabited Spieden Island. Under pressure, the investors shelved the idea of a safari hunters’ island and sold the property.

In Haro Strait, not far from Lime Kiln Point, somebody spots a pod of orcas; few things set the human heart to racing as hard as the sight of black dorsal fins on the horizon. When they break the surface, jumping ten feet or more, the killers show the grace of ballerinas. Hearing them breathe, you find it hard not to feel a sense of mammal kinship. Through their blowholes they spout a blast as grand as a geyser gush—the sight and sound of large lungs exhaling warm air. Cleanly black-and-white, the orca would be ruined by colorization.

One larger whale, apparently the bull, leaps high and crashes down, displacing enough water to flood a subdivision. They move fast. I want to get closer, but we can’t; it is against the law to come within a hundred yards of killer whales or to harass them in any way. From Lime Kiln Point, the nation’s only whale-watching park, the orcas can often be seen thirty to forty yards offshore. In the chill waters of Haro Strait, chasing fish, playing with each other, they seem like regal creatures. Later in the day, I hear a story from one of the naturalists at the Whale Museum in Friday Harbor on San Juan Island. A few harbor seals were sunbathing on rocks near a steep edge on one of the small islands when they were approached by a pod of orcas. One whale snatched a two-hundred-pound harbor seal, then the rest of the pack moved in, tearing the seal apart.

The killer whale has had many friends in this part of the world for at least two decades. Most schoolchildren can describe the orca’s intelligence, its strong family ties, its sense of humor, its dorsal-fin size. Every killer whale in the waters of Washington and British Columbia has been identified and named; their pictures are published in a book, not unlike a high school yearbook. When Winthrop toured Puget Sound by canoe—passing the spot on San Juan Island where orcas play ’most every day—the killer whale was the most feared creature of the deep. Efficient carnivores, a pack of thirty orcas may attack a gray whale, for example, and tear the larger creature apart, shredding the tail flukes, then stripping away the blubbery flanks. Another type of orca attack includes the coup de grâce: forcing open the other whale’s mouth and ripping out its tongue. In such a case, the victim dies from shock and blood loss. The orca also eats dolphins, sea lions and occasional shorebirds.

As recently as the early 1960s the United States government issued bulletins stating that the orca would attack and kill any human in the water. A National Geographic book published about the same time repeated the myth. This perception helps explain the worldwide publicity a man named Ted Griffin received when he purchased a killer whale in 1965 for $5,000 from a group of Vancouver Island fishermen. While press helicopters buzzed overhead and newspaper reporters sent daily dispatches from the sea, Griffin took eighteen headline-filled days to tow his caged orca five hundred miles south to Seattle. He named the whale Namu, put it inside a small tank, and charged admission from the curious who came to see him swim with a creature that was supposed to rip him apart. Soon, Griffin was a celebrity, invited by Pentagon brass to formulate a plan to put the orca to military use. In 1968, the Defense Department purchased two killer whales from Griffin, believing they could be trained as a sort of watchdog on the high seas. Meanwhile, United Artists had paid Griffin $25,000 for the rights to film Namu, The Killer Whale. When the picture was shot off San Juan Island in 1966, a fake whale manufactured in Hollywood was used in place of Namu, who had died in his cement pen in Seattle. The cause of death was listed as drowning brought on by sickness from polluted water.

Griffin proceeded to catch a total of thirty orcas, selling most of them to places like Sea World in Southern California and Florida. By the early 1970s, the killer whale had become the world’s leading aquarium attraction. Nearly forty orcas, more than a third of the Puget Sound population, were captured by aquarium hunters in a ten-year period up to 1976. So, even after the landmark whale treaties of 1966 protected blue and humpback whales from further predation by man, the orca hunts accelerated. Killer whales were netted, sedated, taken from their families and put into tiny tanks for amusement purposes. In the open sea, moving at a top speed of thirty knots, they cruise up to a hundred miles a day. In the cement tanks, their range is usually just several lengths longer than their body size.

Few Puget Sound orcas, conditioned to a stress-free life of roaming in forty-six-degree water with their families and friends of the pod, have lived very long in captivity. At Sea World, they have been taught to breach on command for their food and generally treated like circus dwarfs in the last century. One transplanted orca in Los Angeles was trained to wear sunglasses for a car dealer’s ad. Like the sea otter and the wolf, the orca is known to have a well-developed sense of humor in the wild, playing tag with friends, doing cartwheels and back flips. But at aquariums such as Sea World, their humor appears stiff and forced—Pavlovian routines of hoop-jumping and fin-standing in order to get their dinner. Some have rebelled and turned surly or refused to eat; a few captives have died of anorexia, baffling trainers who can’t understand why such an intelligent mammal would starve itself to death. Most of the captured orcas have died well before their natural life expectancy of seventy to eighty years.

In the early 1970s, a onetime Vancouver Aquarium whale expert named Dr. Paul Spong led a worldwide campaign to keep the orcas free. While Spong fit the generational stereotype—during summer months, he lived in a treehouse off Blackfish Sound and played his flute to the whales as a way of communicating with them—his early research was gaining a foothold of credibility in the scientific community. Initially, Dr. Spong was laughed at when he talked about similarities between whale and human brains and claimed that orcas had a sophisticated way of communicating with one another. By comparing the evolution of human brain size with that of orcas, Spong concluded that the cerebral cortex—that part of the brain which houses language, abstract thought and logic—is strikingly similar in the two mammals; no other warm-blooded creatures have brains of such sizes compared to their body weight. In 1976, while Spong was speaking at an orca symposium at Evergreen State College in Olympia—a school whose official mascot is the geoduck, the “large queer clam” which so fascinated Winthrop—eight killer whales were captured nearby in Budd Inlet, just a few miles from the Nisqually Delta. The seizure, by hunters from Sea World of Japan, made front-page news for days on the West Coast. A few of the whales were released from their holding nets by midnight saboteurs. The others were ordered released by Governor Dan Evans.

Soon after the Budd Inlet capture, the state banned all types of commercial whale-hunting in Puget Sound. This upset columnist George Will, who wrote a piece in Newsweek criticizing Washington Secretary of State Ralph Munro. A fourth-generation Northwesterner, Munro wondered why children of Washington State should have to travel to San Diego and pay ten dollars to see a creature whose home waters used to be in their backyard. Munro said people in the Northwest “are tired of these Southern California amusement parks taking our wildlife down there to die.” His statements set George Will off. “If Sea World is denied a permit for ten orcas,” Will wrote, “I hope 230 million Americans go to Puget Sound, unfold lawn chairs on Munro’s lawn, ask for iced tea and watercress sandwiches and watch the whales. It will be good for their souls and it will serve him right.”

The orcas were never captured. Ted Griffin retired from the business of riding killer whales around by the dorsal fin in small cement pools. He was forced out, he admitted, by a tidal shift in public opinion—the wolf of the sea had become a teddy bear. But just as the orca was given its freedom, a group of bottlenosed dolphins were drafted into indentured service at the Trident nuclear submarine base at Bangor, on Hood Canal. These swift-moving mammals, part of the same family as killer whales, are being taken from their home waters in the Gulf of Mexico and trained to guard nuclear submarines in Puget Sound. Having marshaled some of the best scientific brains to build an underwater nuclear arsenal that can destroy the planet, man now attempts to put the smartest creature of the sea at work as a co-conspirator.

At high tide, the horizon at Bowerman Basin is covered with the pastel undersides of a million sandpipers. They come here from South America, heading north; or they fly down from the arctic, heading back to Colombia. In small part, the basin reminds me of the Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania, the great watering hole of nature where pink flamingos blot the sky and sleepy lions and moody water buffaloes roam the crater floor. In the ten-thousand-mile length of the Pacific flyway, there is no better truckstop than here, a mudflat just outside the broken Pacific logging town of Hoquiam on Grays Harbor. The town lost almost a third of its population during the last timber recession; now log prices and demand are high, but Grays Harbor County still has an unemployment rate three times the national average. The winds blow steadily in from the Pacific; logs and jobs sail steadily out to Asian countries that no longer have forests.

For migrating birds, the old wetland haunts of the West Coast are mostly gone. Hungry and desperate, they finally land in the mudflats of Bowerman Basin. Unlike the Nisqually Delta to the north, the basin has tidal goo uniquely suited for sandpipers. Frantically digging into the mud with their pencil-thin beaks, the birds gorge themselves on marine life, carb-loading for the two-thousand-mile flight ahead, the final leg north. Their stomachs on autofeed, they slurp and peck, and chomp and slurp on a patch of tidal mud. Then, something happens, something changes, and they hit the sky—a sheet as big as a stadium flag.

I arrive at Bowerman Basin on a day when many in New England have yet to see their summer songbirds. For some reason, they didn’t show up. Shutters in New England opened to spring mornings, bulbs came forth in the usual color, but there were no songbirds in the land of Winthrop. They must be late, delayed by a seasonal quirk. But then spring dragged on, and still no sound of the early morning worm-chasers. For most people, it’s a mystery. Others blame the loss of wetlands and estuary stopovers. We are losing plant and animal species in North America at a rate a hundred times greater than before the arrival of Europeans. Most of us don’t notice until the morning begins with no other sound but the dreary radio news of traffic tie-ups, or the backyard is overrun with a certain type of insect, or the sun burns hotter than ever.

In the Bowerman Basin area, civic leaders think they should continue filling in the marsh; already, a third of the basin has been covered up by the Army Corps of Engineers, acting on some vague plan by local business leaders. They have no specific economic outline; just a gut sense that mudflats can’t mean much of anything to a broken community. The mayor of Hoquiam, a timber town so depressed its leading citizens are paying $100 a night to hear motivational speakers from Seattle tell them how to feel good about themselves, says he eats shorebirds for lunch, a line that gets a big laugh at Rotary. His remark is a response to a proposal to save the last bit of mud in the Bowerman Basin. With four thousand acres of Grays Harbor marshland already filled in, conservationists want to save the remaining thousand or so acres for the sandpipers. The basin hosts the largest concentration of these birds in the West. Hoquiam civic leaders are against the idea of a wildlife refuge; they think filling in the mudflats is a better idea: solid ground in Bowerman Basin will make it even easier to export the logs which are yanked out of the fast-disappearing rain forest to the north. But nobody knows for sure; the word in the Hoquiam business community, freshly rejuvenated by the Seattle motivators who tell them they can do anything as long they feel good about themselves, is that mud and birds don’t add up to a whole lot.

When I ask for directions to the basin, the Chamber of Commerce folks shrug. Apparently, I’m not alone. Dozens of people have dropped by the visitors’ center this morning—up from Portland, down from Seattle—inquiring about these goddamn sandpipers and the stinking mud. A woman gives me a brochure which tells all about the world’s first tree farm up north, and I tell her I don’t want to see a bunch of uniform-sized, corporate Douglas firs, thank you. I want to see the sandpipers. Well, then go out past the mill and the loading dock facility until you get to the airstrip, you can park there. But you’re on your own.

At Bowerman Basin, about twenty people with cameras are positioned at different spots, sitting in the grass onshore or wading through the mud. I feel like a visitor to Capistrano before the hordes descended on the little mission town to watch the returning swallows. The birds don’t seem to mind the human presence; beaks down, they slurp and chomp. I find a weather-beaten log and settle in. I start to read something I brought along; ten minutes later, when I look up, my log is surrounded by a swarm of birds. I watch them for perhaps twenty minutes, and then they swarm away to another location in the mud. Hitting the sky, thousands in one mass fly in unison at a high speed. As natural thrills go, this one gets the adrenalin pumping. In the distance, logs are stacked to the low end of the cloud cover, putrid smoke belches from a mill, and the people in the broken town wonder what to do to save their community, and I wonder: in all the West Coast, is there no room left for a bird that only wants a thousand acres of mud?

In New York a month later, I meet a man who lives on the forty-second floor of a building in the Lincoln Center area, two blocks from Central Park. He strikes me as a sort of graying genius, in his mid-sixties with a wrinkle-free face and thick glasses, the kind of man who can talk for an hour without taking a breath because his head has been buried in a computer screen for so long. He works at his terminal in sweat pants, massaging questions through his IBM. When he talks about his home, he says he’s an environmentalist, angry at skyscrapers which block the sun from Central Park, incensed at New York’s garbage being dumped at sea. As we talk, he proudly points to the view across the Hudson River to New Jersey. It’s the kind of view I used to think I wanted, in the heart of the world’s greatest ambition refuge, the streets pulsing with the kind of activity one needs to lead a full life.

I ask the New York environmentalist about estuaries: are there any fish or migrating birds across the way where the Hudson River empties into the Atlantic? I tell him about the Bowerman Basin; the very week I’m in New York, Congress votes to set aside part of the mudflats in Grays Harbor for the sandpipers. He takes off his glasses and gives me a quizzical look, blinking. What do you mean? I ask if the Hudson and Atlantic convergence fosters any marine life. He shakes his head and says you wouldn’t want to eat anything that came out of the water below, then points to the bank that rises up from the water, New Jersey, and the narrow band of mud at the foot of the cliff.

“The estuary, you mean? Is that where it is?”

“I guess,” he says. “I’m not sure what you call it—I’m not familiar with the terms—but isn’t it pretty?” I tell him not to apologize; some words leave the language when they no longer have any use.