TALK ABOUT THE intervention of fate! Though I had agreed to consider writing a foreword for a new book coauthored by my friends Lou Grumet and John Caher, the manuscript sat temptingly on a table in my office, but it was a long reach across several piles of documents with due dates on them. Then very early one Friday morning, I found myself at home sprawled on the hallway tile floor, having taken a bad fall while racing from the bedroom to answer the cell phone plugged into the kitchen wall. When I finally made it to a doctor, he pronounced no disaster and ordered light pain medication, lots of ice for the knees and forehead, and my legs raised whenever possible. The perfect prescription for plunging into the manuscript. There I was, Friday afternoon through Sunday evening—from sofa to armchair to bed, always with the manuscript in hand.

Not for a moment do I suggest that you pursue such a pathway into this book. Just pick it up the usual way. It’s a treat, not a treatment.

In writing this foreword, I now put all personal involvements aside, most especially my own participation in the fascinating Kiryas Joel cases as a judge of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York. So, what precisely makes this book such an engaging read for each of you?

I begin with the fact that the book is a great introduction to a world we all should know much more about: our government—each of the three branches and their interactions with one another, from the principles envisioned by our founders centuries ago to the implementation and protection of those principles every single day by our contemporaries in a radically changing society. That’s hardly a day at the beach, I admit, and most of us, regrettably, avoid it, satisfying ourselves with merely grumbling and complaining. But this book is a compelling introduction to the subject told through a single lens, and it could not be more beautifully or articulately illustrated, with good, solid introductions to each of the participants, from our nation’s founders to today’s governors, legislators, political leaders, and judges, and the human beings actually impacted by their choices.

Second, the lens itself is a subject of immense interest. The particular focus of the book is on Satmar Hasidim, a religiously homogenous, politically muscular group situated in Orange County, New York, and on education services for their many, many children with disabilities and special needs. This subject embraces a rainbow of fascinating issues, from First Amendment constitutional protections (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”—in other words, freedom to and freedom from), to political deal makers and courts generally settling (and unsettling) the reach of these fundamental concepts, and ultimately to the power of relentless persistence.

Never is the reader left in the clouds on these mind-wrenching, yet critically important, issues. Each matter is graphically tied to people captivatingly described (and actually quoted) in great detail, offering a unique, singular view into the operation of their hearts and minds. You’re on the scene from day one, meeting the Satmar and their neighbors, strategizing with Satmar leaders on how to educate Sheindle Silberstein and other Satmar children with similar difficulties in the comfort of their religious and cultural tradition. You’re at the table through meetings with state and federal political leaders, ultimately securing actual state legislation to enable the Satmar to establish their own special school district. You’re in several courtrooms, both presenting and hearing oral argument. You’re even in the conference room of the Supreme Court of the United States for heated inside exchanges and decision dynamics among the justices (thanks to the writings and notes of Justice Harry Blackmun).

It is, of course, no surprise that long after the Supreme Court’s decision in this case, the swinging pendulum of legal and human entanglements on similar “freedom to and freedom from” issues has remained in perpetual motion in Satmar and other communities, and in courts around the nation. I will say no more than to endorse first my friends’ view that Kiryas Joel was a crucial benchmark at a crucial juncture, and second the closing words of their book: “Eternal vigilance is indeed the price of liberty.”

Looking back to that fateful Friday fall that took me deep into the manuscript, I cannot recall any accident in my life that yielded such a rich reward.

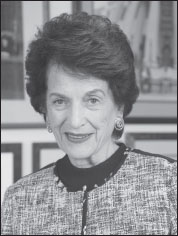

Judith S. Kaye, the first woman to serve on New York’s highest court and the state’s chief judge for fifteen years, went on to become of counsel to the Manhattan law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. She passed away in 2016.