Five

I SURE

MISS

ALL

OVER BUT THE

SHOUTING

.

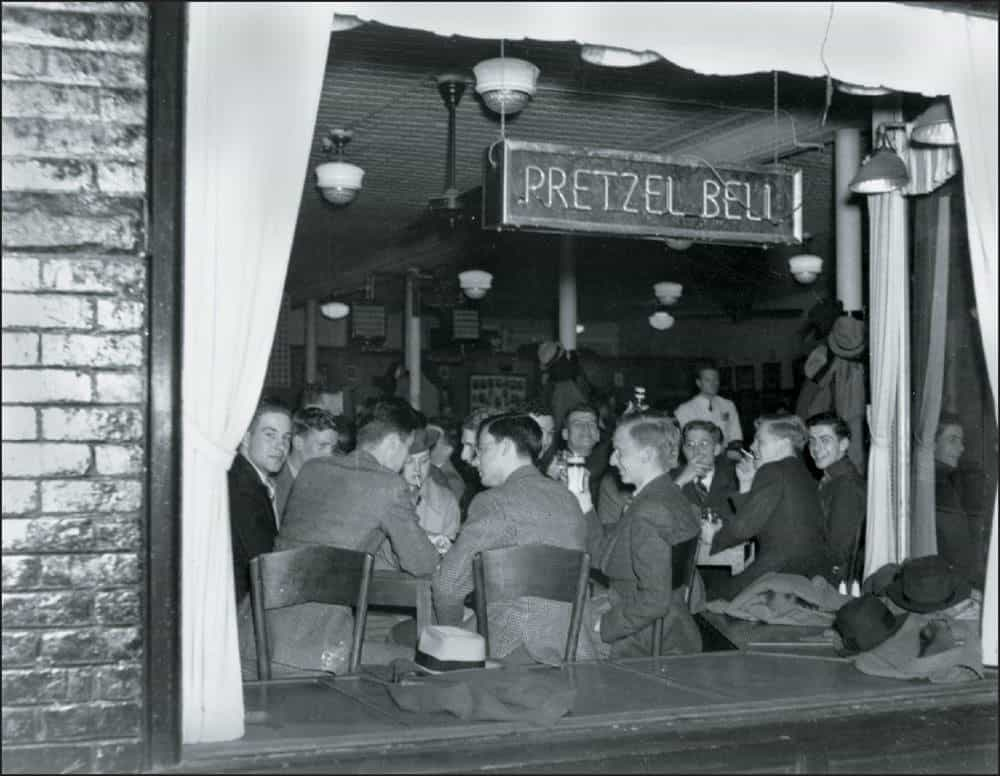

When people heard about this book on iconic Ann Arbor restaurants, the common response was, “Is the Pretzel Bell going to be in it?” Drake’s was a close second. Sadly, the originals are gone, as are many others. But here is a chance to briefly cry in beers and limeades and fondly remember those places frequented not so long ago. The combination bell and bottle opener (right) was a Pretzel Bell party favor on New Year’s Eve 1934. (Authors’ collection.)

STILL

RINGING

.

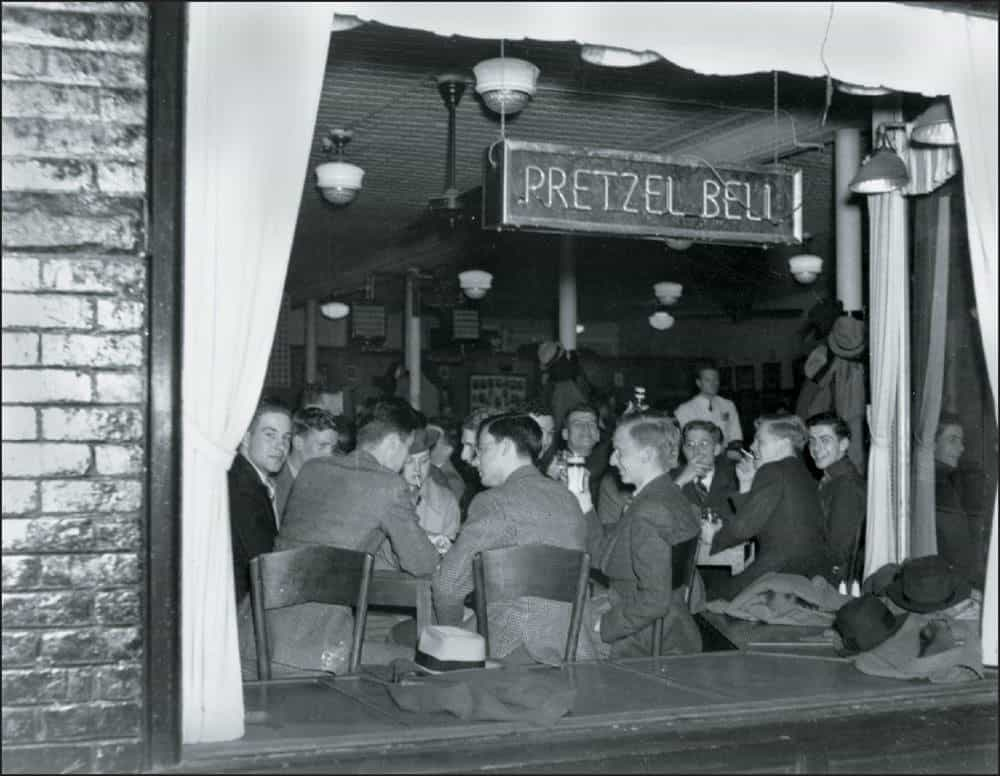

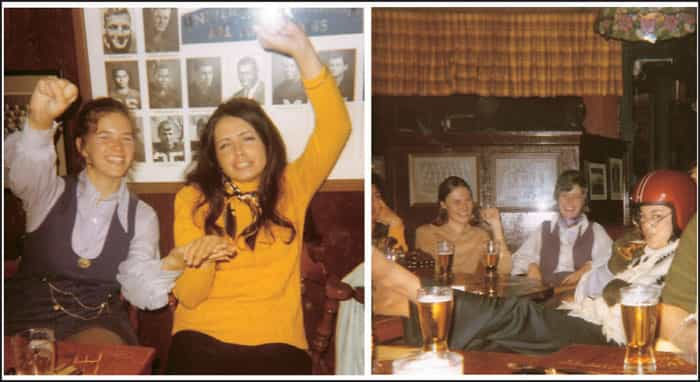

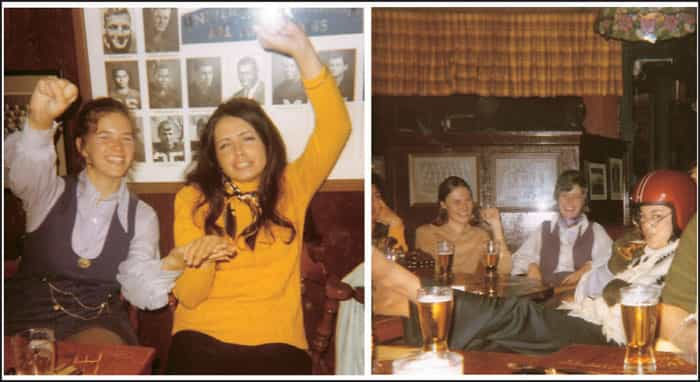

Clint Castor Sr. opened the Pretzel Bell in 1934, shortly after the repeal of Prohibition. And from that moment on, the restaurant at 120 East Liberty Street became synonymous with the Michigan “Go Blue” spirit. The Pretzel Bell seemed to celebrate everything Ann Arbor—its past, its present, and, above all, the University of Michigan Wolverines. It was a veritable Ann Arbor museum, featuring the original bar from Joe Parker’s Saloon and the richly lacquered (and heavily carved) tables from the Orient. The dinner bell that alerted folks to phone calls once rang for athletic events at Ferry Field; the larger bell that heralded Michigan victories, parties, and milestones was a gift of Alpha Delta Phi. More than 500 photographs, many one-of-a-kind Michigan team photographs dating back to 1883, lined the walls. It was the place to be, and to be seen, from Fielding Yost to Pres. Gerald R. Ford, Charlie Gehringer, Ethel Barrymore, and Artur Rubenstein. Both color snapshots below are from Pretzel Bell in the mid-1970s. (Above, courtesy of Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; below, courtesy of a private collection.)

LAST OF THE

BELL

.

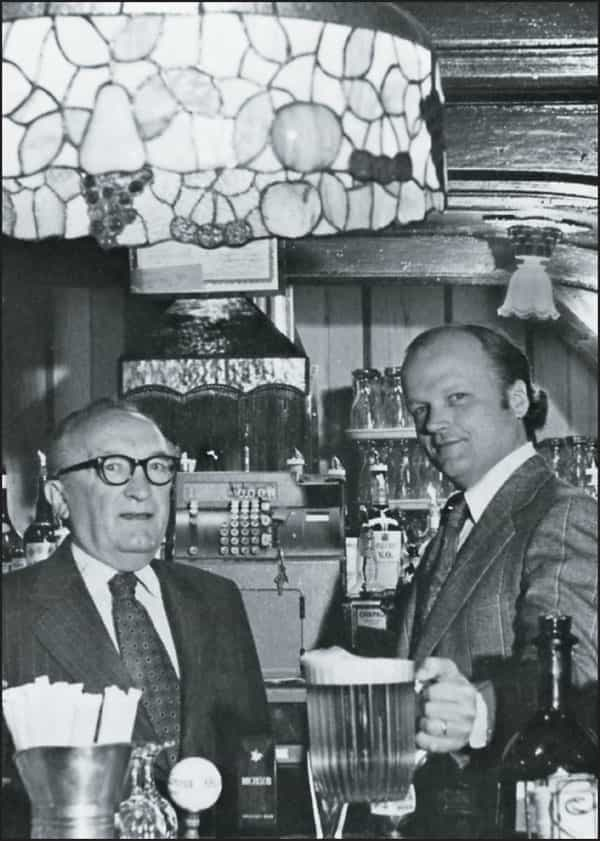

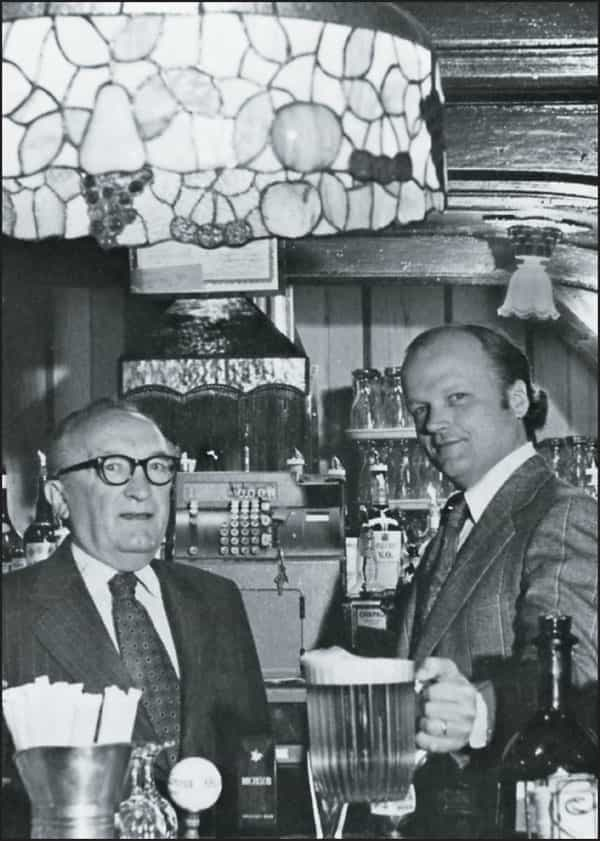

Going to the P-Bell was an Ann Arbor rite of passage. It was the place to go to celebrate a Michigan victory—bells ringing, beers raised, and a deafening din, intermittently overshadowed by a chorus of the victors. It was yet another place where Fielding Yost would use plates, glasses, shakers, and utensils to transform his table into a football-oriented variation of a chessboard and challenge students to out-strategize him. In 1936, Leopold Stokowski stood on a chair and led revelers through “The Victors” and “I Want to Go Back to Michigan.” It was that kind of place—a party with good food and good beer and lots of Michigan spirit. In time, Clint Castor Jr. (pictured on the right of Clint Sr.) took the helm, and he also opened a short-lived place along South University Avenue known as the Village Bell. The Bells rang up their last sale in 1984, when the Pretzel Bell went dark, and the party was over. (Above, courtesy of Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; right, authors’ collection.)

HITS THE

SPOT

.

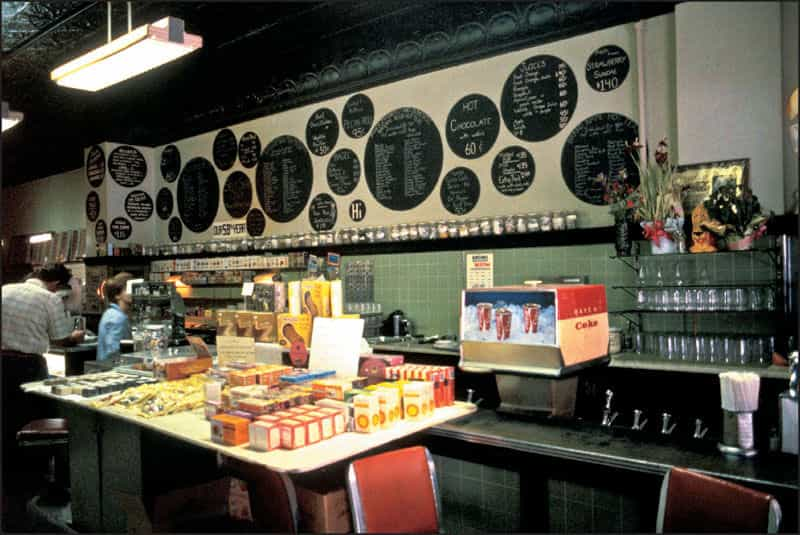

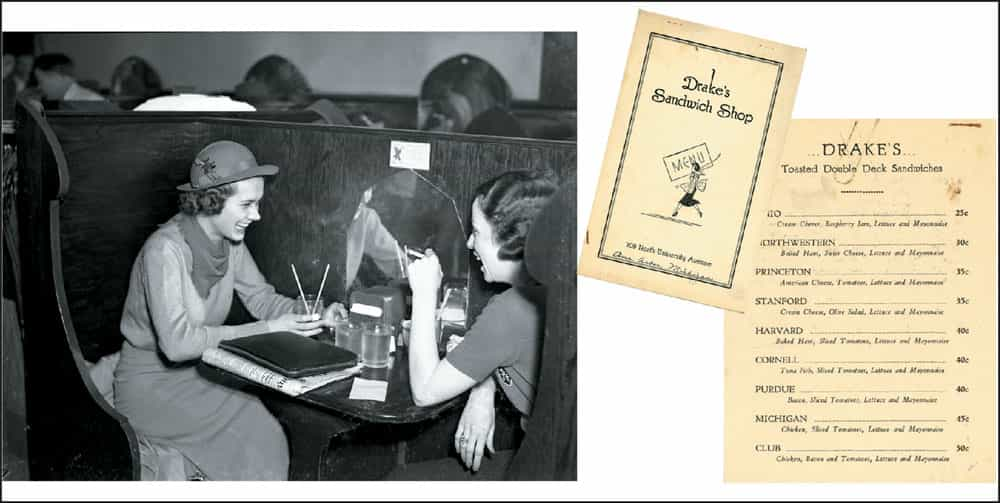

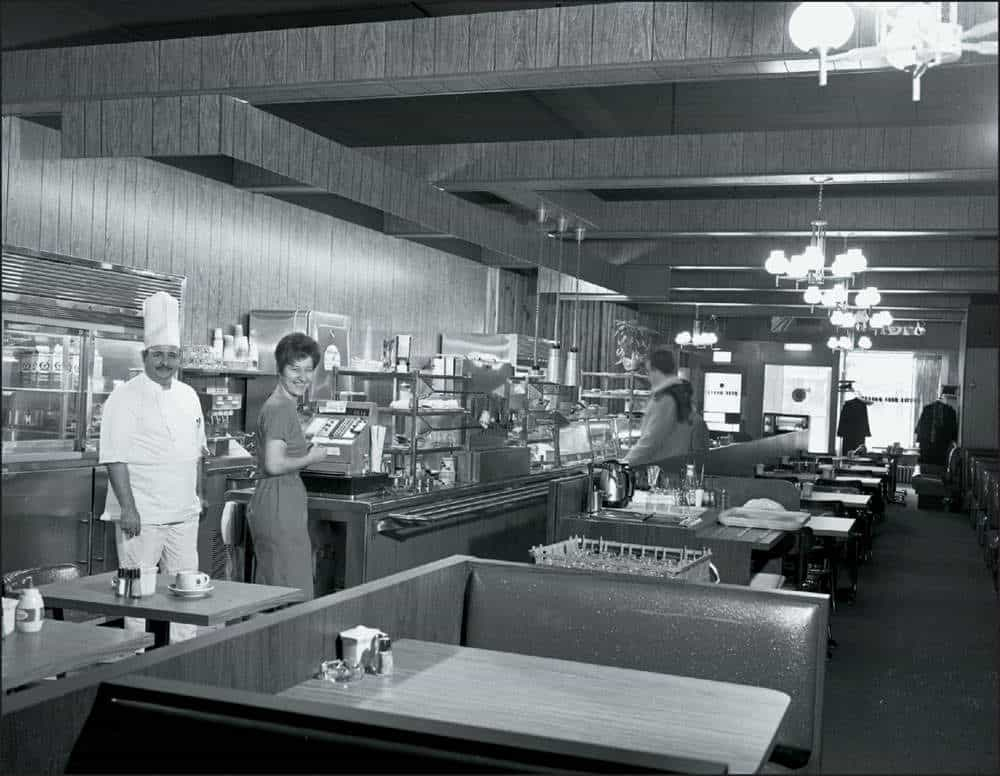

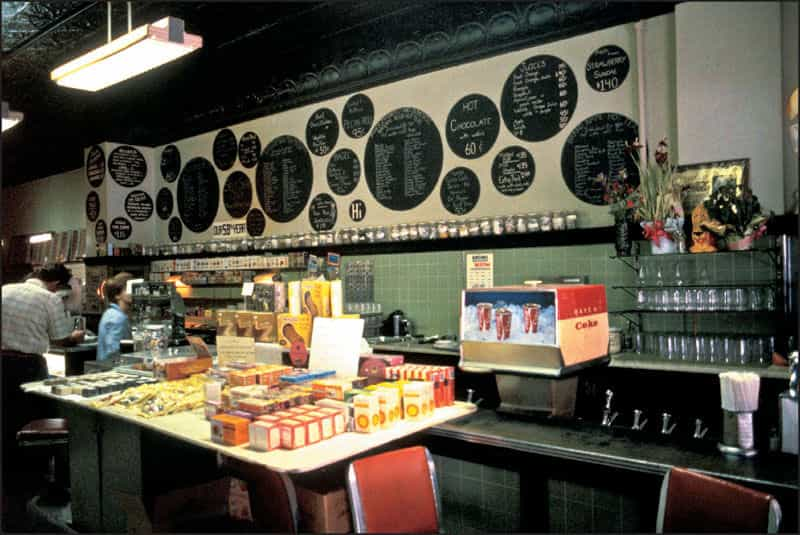

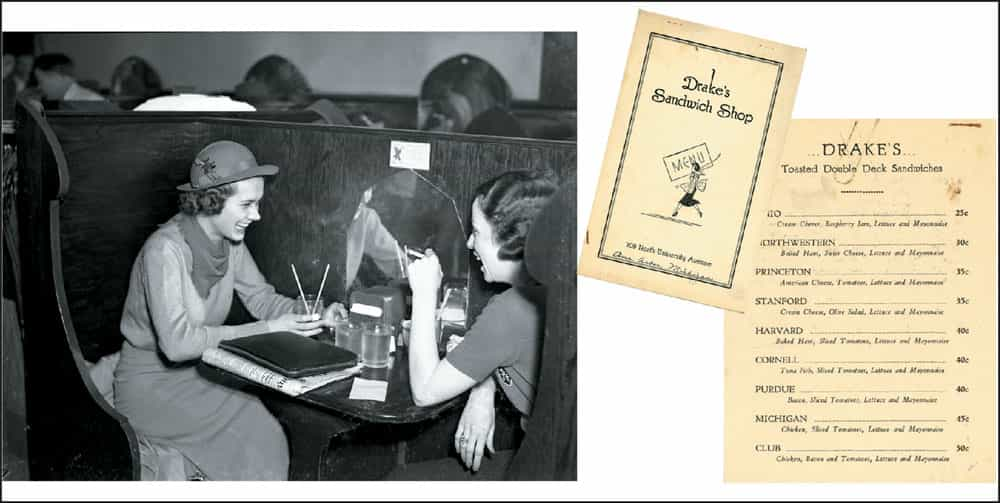

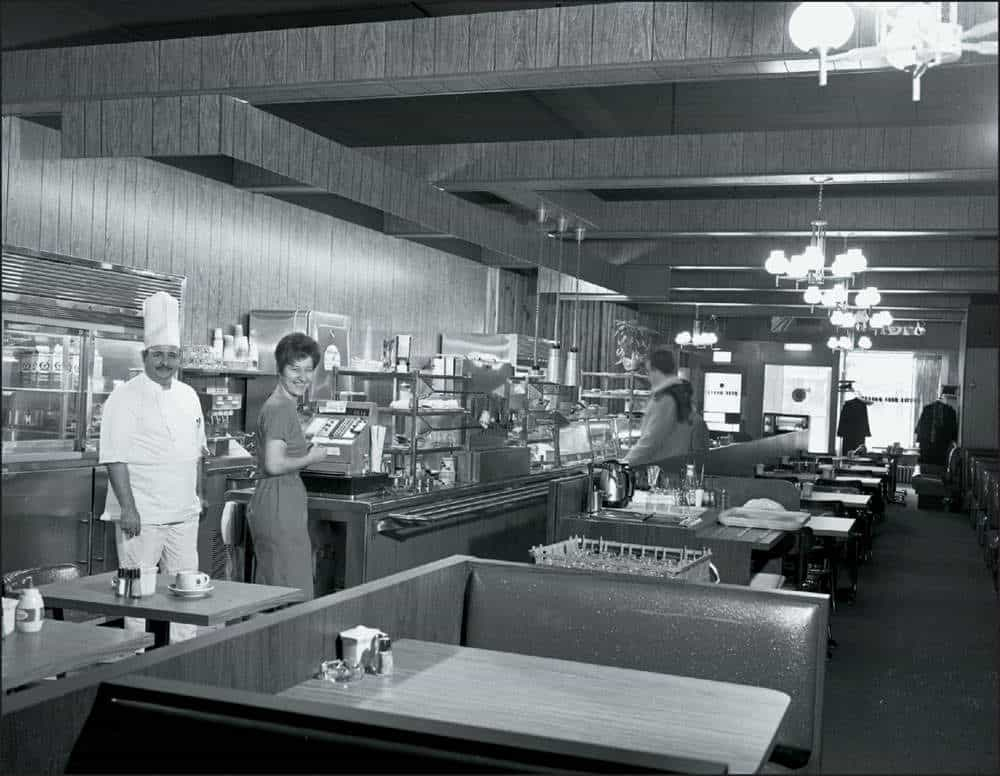

Drake’s gets more wistful looks than just about any Ann Arbor spot. For over 60 years, Truman and Mildred Tibbals perched on stools and held court in this charming candy, sandwich, and tea shop. The hospital-green walls were lined with hundreds of candy-filled glass jars ready to be scooped into iconic red-and-white striped bags by smock-wearing helpers. Chocolate cordials were a favorite, and Drake’s was the first to have gummi bears. Many still drool over its fresh-squeezed limeade and pecan rolls grilled in butter or unusual sandwiches like peanut butter and bacon along with a pot of Ty-Phoo tea. Customers ordered by writing on a green pad with a tiny attached pencil. The window displays were also a treat: “electrified” chickens picking at candy corn, and, in the fall, miniature maize and blue footballs. (Both, photograph by Jim Rees.)

SECRET

RECIPE

.

Drake’s upstairs was the Martian Room (formerly the Walnut Room) for dancing in the 1940s, and later, it was a cozy spot for dates to perhaps share a black and white sundae (marshmallow and hot fudge) in one of the high-walled booths. The Stanford sandwich was also popular. Here is the recipe: grind green olives in a meat grinder, drain the olives and add a bit of Hellman’s mayonnaise, slather cream cheese on a bagel (or bread), and put the olive mix on top. Drake’s was also a hangout for local cops. While working at night, Truman Tibbals would leave the back door open so they could come in and get themselves a piece of pie or a sundae. It was known to dispatchers as a “709”—the address at Drake’s. This comfort food classic closed in 1993, but there’s no shortage of great food memories. (Above and below left, courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; below right, authors’ collection.)

THE

WHATCHACALLIT

.

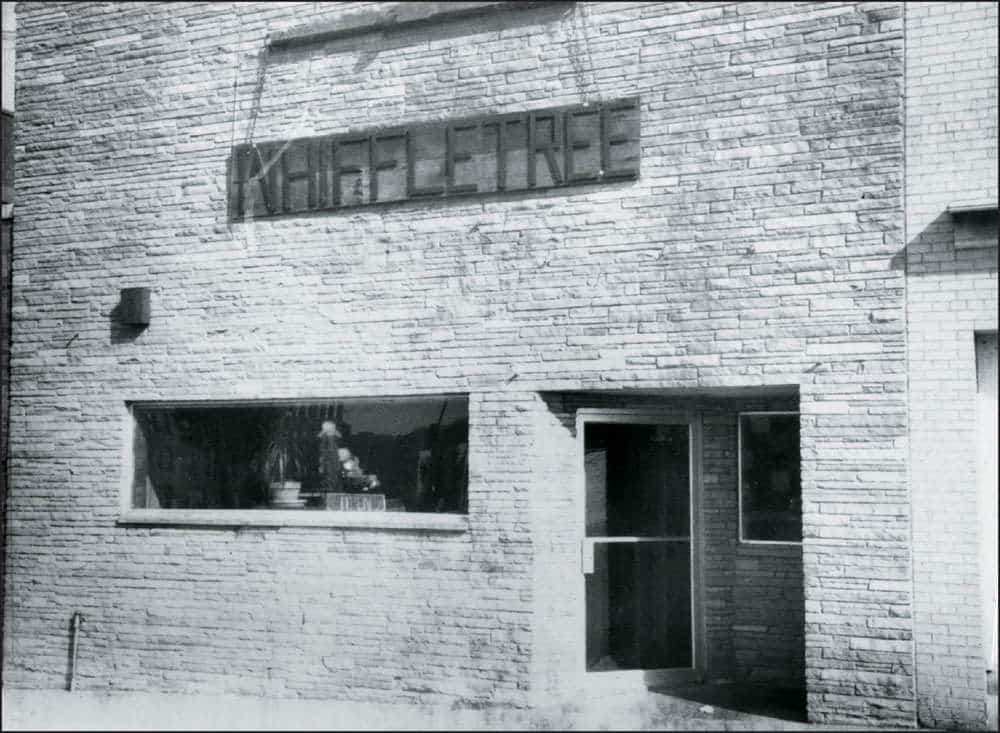

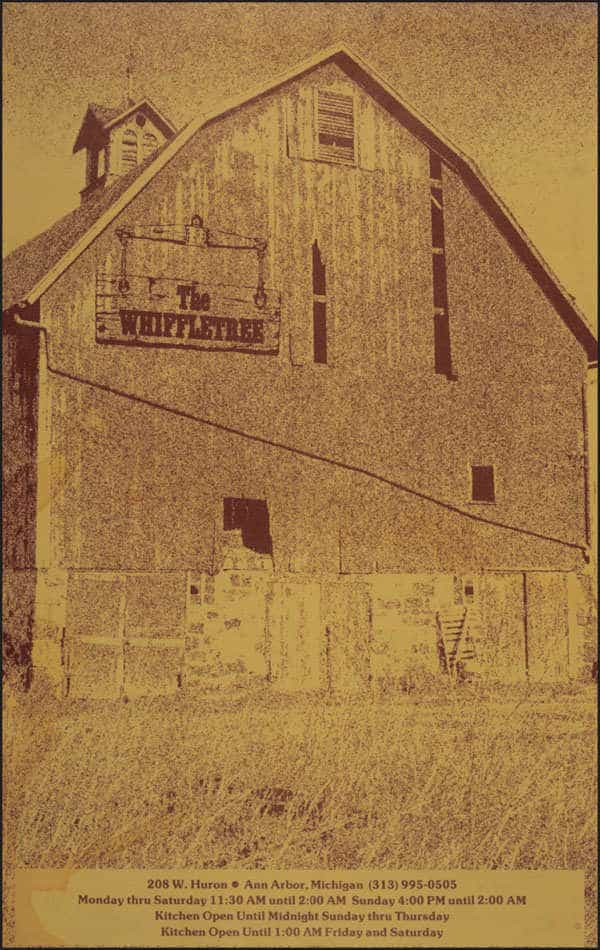

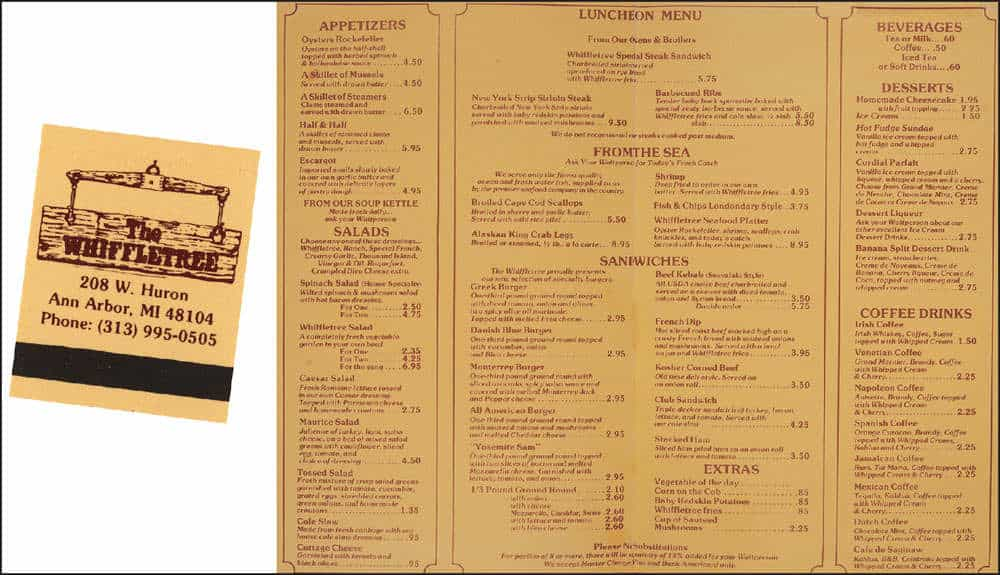

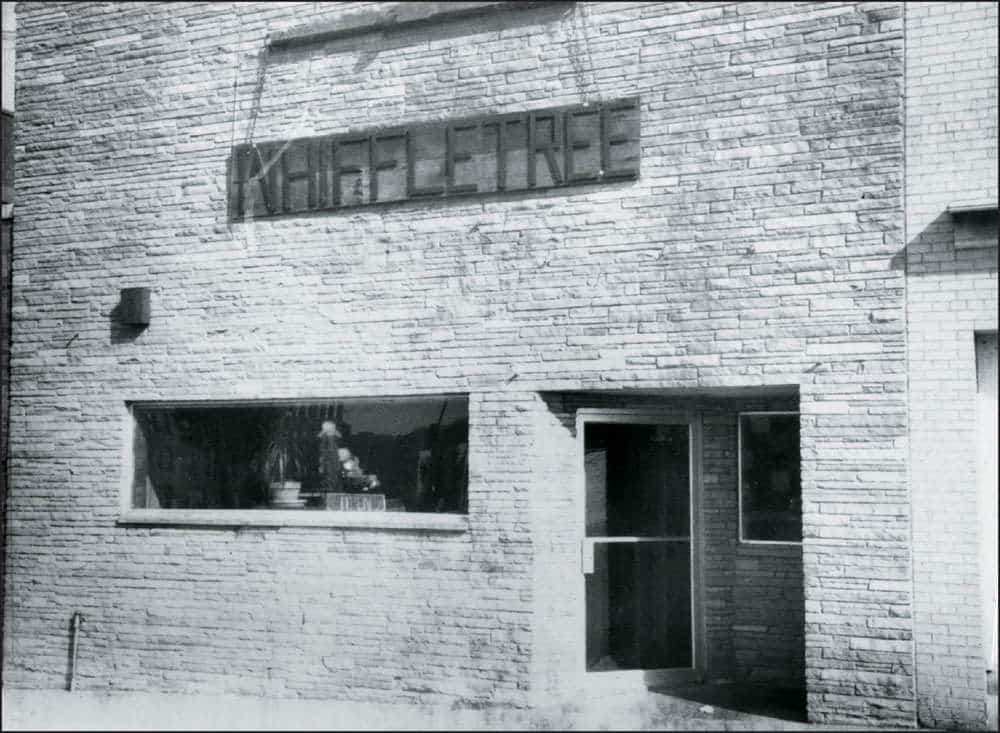

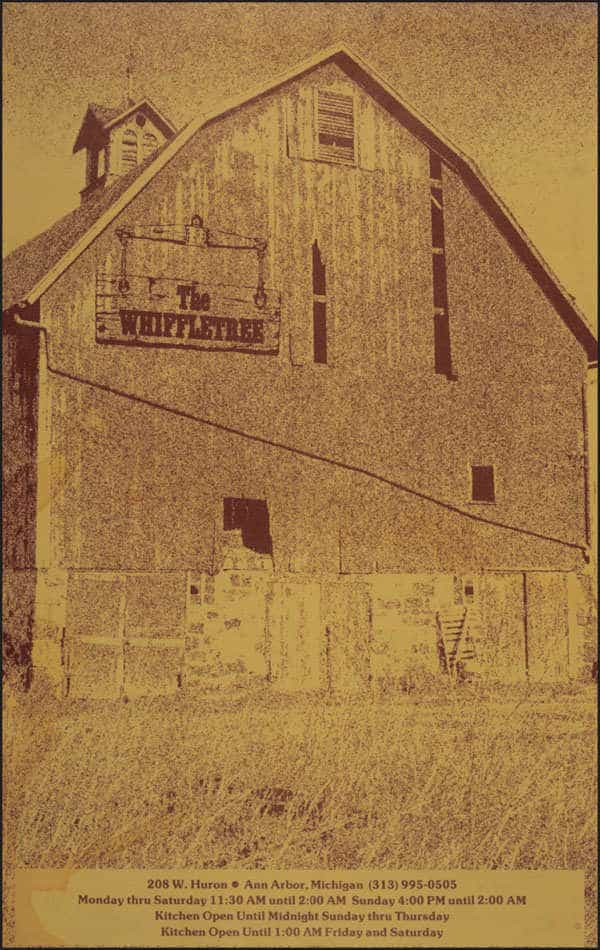

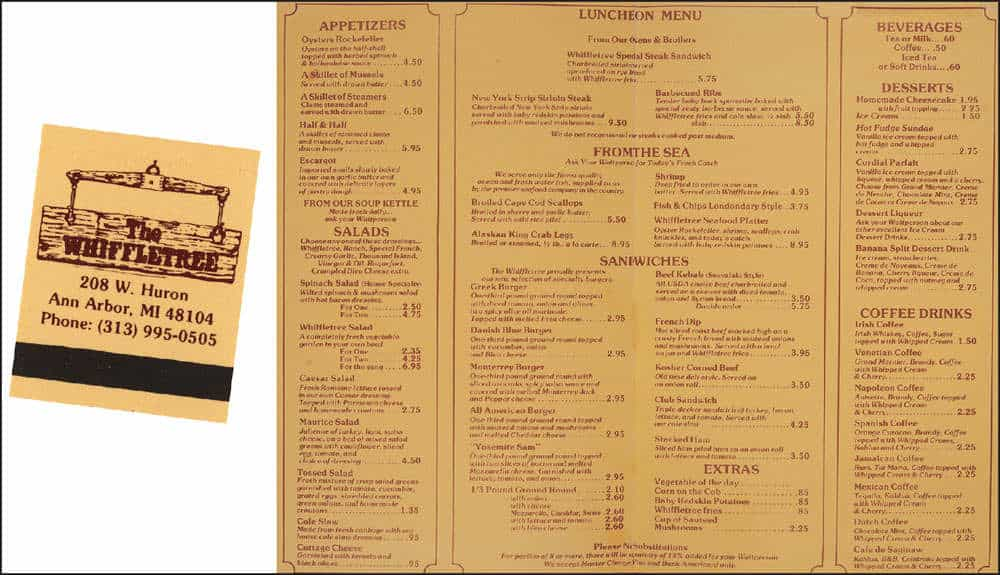

It was almost called the Whippletree or the Singletree. But the Whiffletree won out, and the former monument company, then the Century bar, was decorated with many of the steering devices that attach to a horse’s harness. In fact, the interior was wood from a barn torn down by owners Robbie Babcock and Andy Gulzevan. The Whiffletree on Huron Street was an eclectic place that drew just about everyone from townies to out-of-towners. Successful from its opening in 1973, the menu ranged from affordable sandwiches (the Yosemite Sam burger) to affordable luxuries (Dover sole and other fresh fish flown in daily). Former acolytes can rattle off their favorites, like mushroom caps, king crab legs, and especially the fries. The Wednesday night buffets were legendary—they even included prime rib. Luckily, seating increased from 100 to 340. (Above, courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library; left, courtesy of the JBLCA.)

LET THE

WHISKEY

FLOW

.

Robbie Babcock, who became sole owner after three years (and also owned Robbie’s at the Icehouse) remembers one football Saturday where the line to get in was so long that it crossed the street and merged with the line to get into the Old German. The Whiffletree had its share of celebrities, too. Arthur Miller was such a fan that he brought his acting troupe there every time he was in town. Jimmy Stewart, Vincent Price, and Fleetwood Mac ate here, as well as U of M sports legends like Desmond Howard. Even after dinner, there were special touches, like Robbie’s mom’s angel food cake and their famous Irish coffee. In fact, in an average week, they went through four cases of Irish whiskey—a record in Washtenaw County. Sadly, one summer night in 1987, a fire a few doors down spread and collapsed the roof of the Whiffletree. It was never rebuilt. Almost 30 years later, many still mourn. (Both, courtesy of the JBLCA.)

ROUGH

START

.

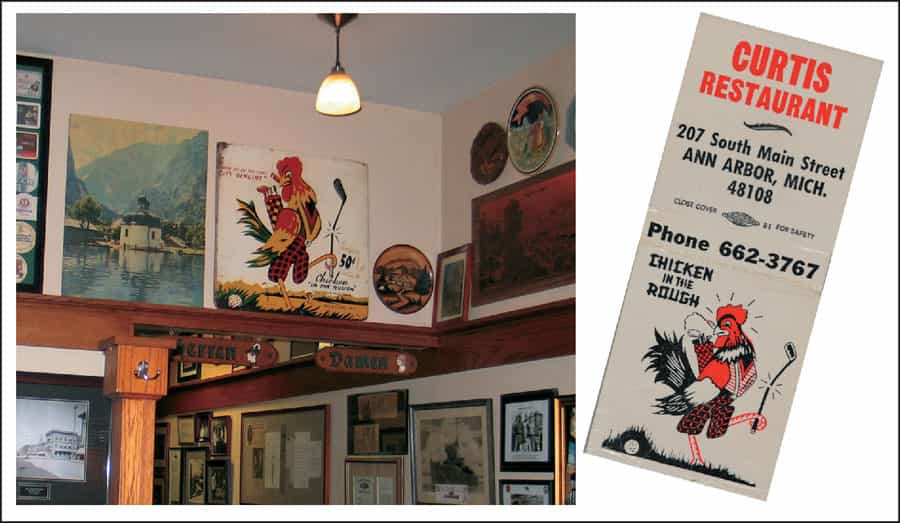

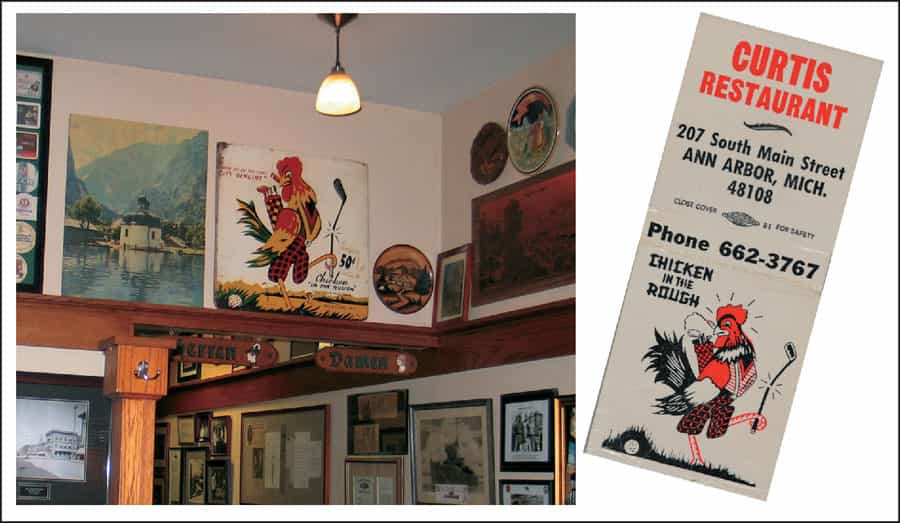

Chicken in the Rough was one of the first restaurant franchises in the country. Started in 1936 by a Dustbowl couple looking to rebound from the Depression, a Chicken in the Rough dinner was described as “A half fried chicken, served unjointed without silverware, with shoestring fried potatoes, hot biscuits and honey.” Along with the meal came a hand towel and a handy (and colorful) Chicken in the Rough finger bowl (below), brought to the table full of sudsy water for easy cleanup. The concept was a big and tasty hit. Over time, it grew to 235 outlets worldwide. Ann Arbor’s most notable outpost was the Curtis Restaurant (left), founded in 1947 by George Curtis, who lived above it. (Left, courtesy of Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; below, authors’ collection.)

LATE

NIGHT

BITES

.

Curtis was one of the first restaurants in town to stay open until 2:00 a.m. Later, it became Curtis Beef Buffet, then the Full Moon Café, and now it is the Ravens Club. To try Chicken in the Rough, head to the Palms Krystal Bar in Port Huron, Michigan—the last US location. It is worth the trip. At one time, Metzger’s (below) also featured Chicken in the Rough, and they still display the old sign in their dining room. (Above, courtesy of Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; below, authors’ collection.)

ALL

TOGETHER

NOW

.

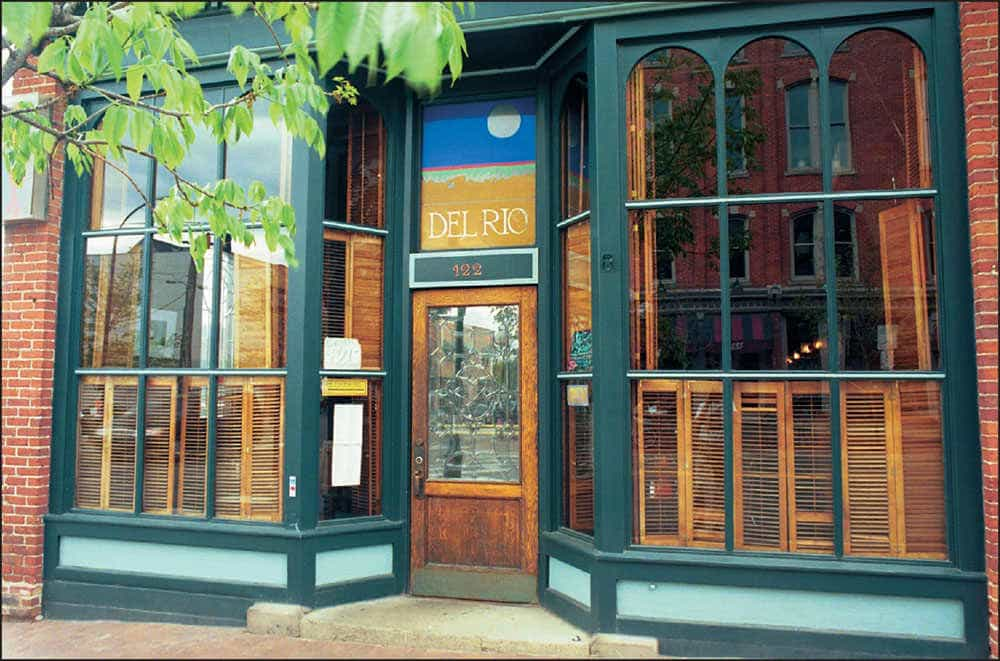

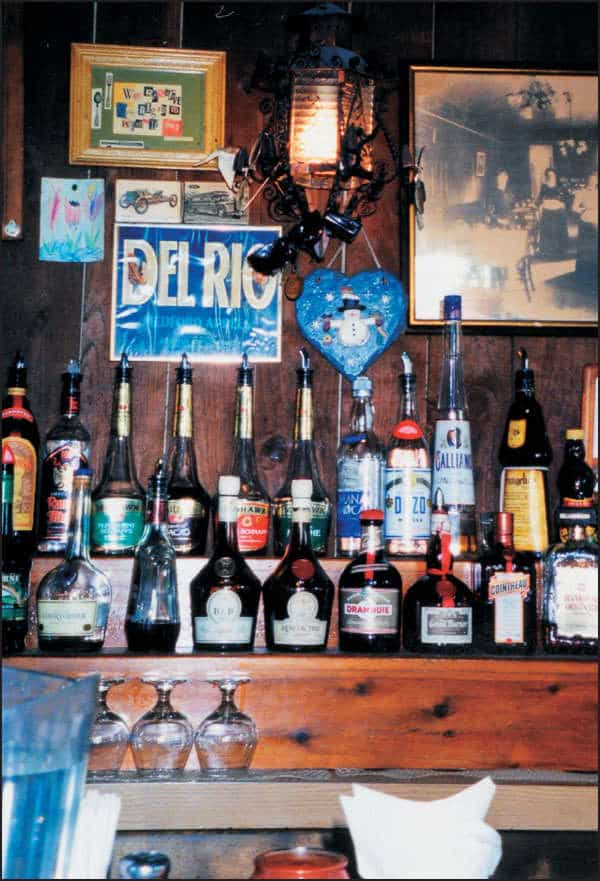

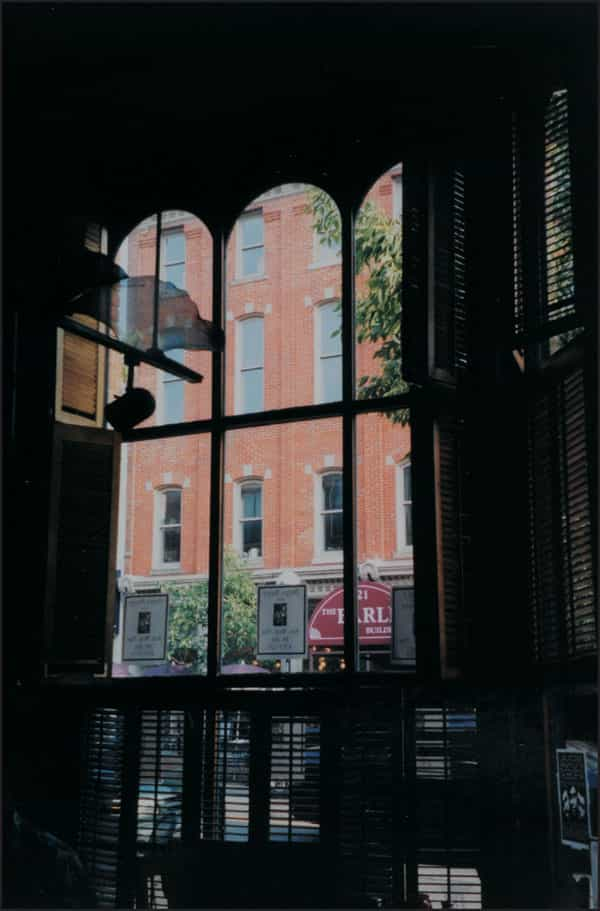

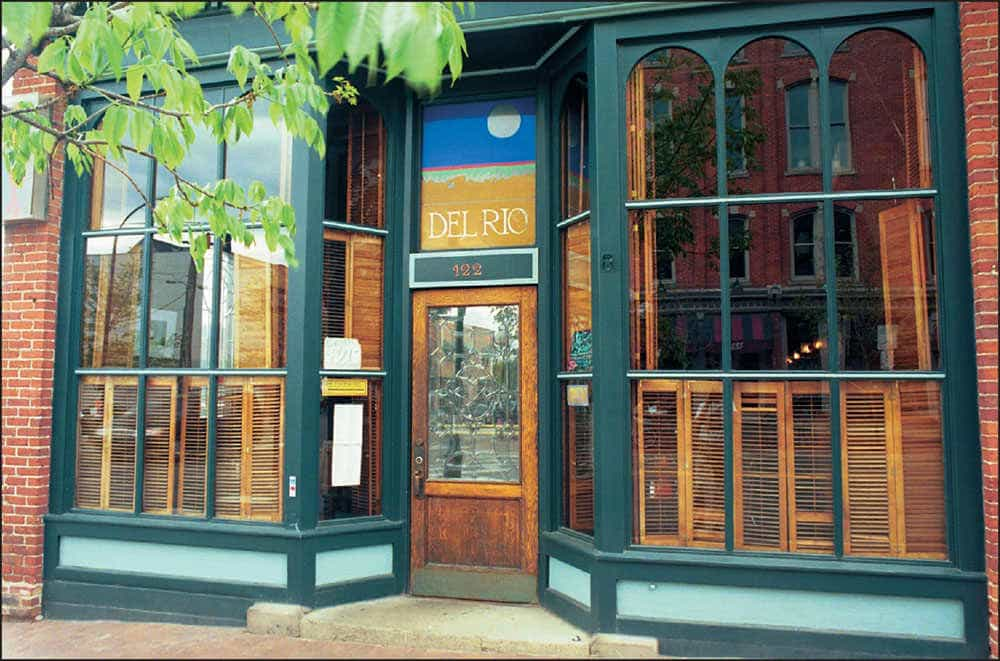

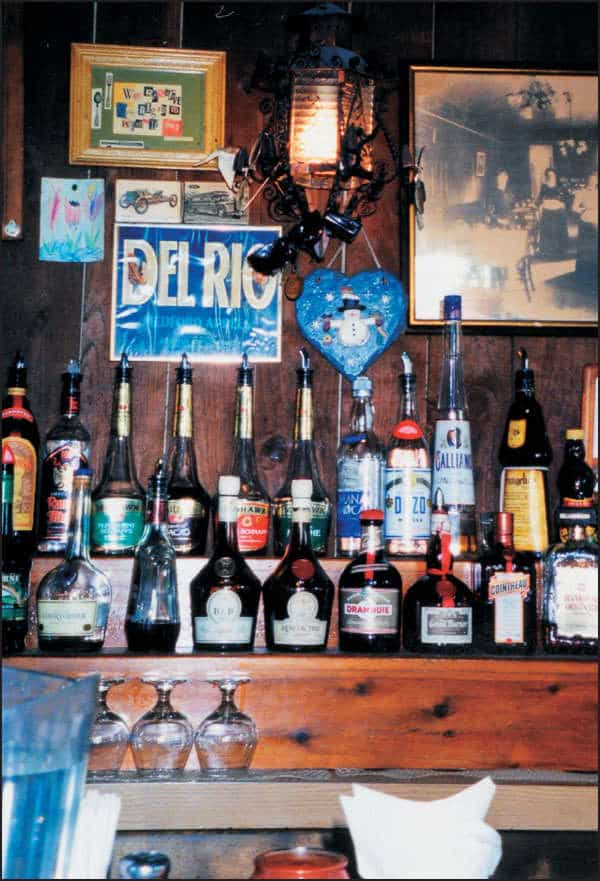

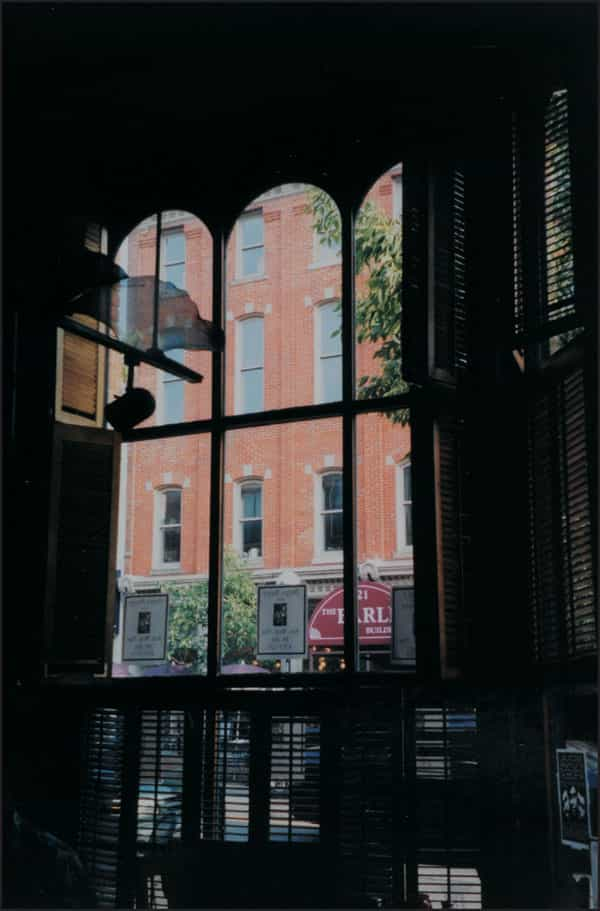

Part political movement, part social experiment, and all landmark, the Del Rio had the best bathroom graffiti. Started in 1970 by Rick Burgess (who later owned the Earle) and Ernie Harburg (whose father wrote The Wizard of Oz

lyrics), it ran as a cooperative, with the staff deciding everything. Antiwar and feminist groups met here, part of the cultural mix as eclectic as the music tapes along the walls. Burritos and chewy whole wheat pizza were popular, along with the Zapata and the tempeh Reuben. Many menu items were named after the staff, like the Detburger (named for cook Bob Detweiler). Chef Sara Moulton started here. Amazingly, this hippie halcyon lasted for 30 years. Then new owners changed things up, and the spirit was gone. It closed in 2004. But for many, late afternoon sunlight streaming through the windows, live jazz on Sundays, and sipping a Bass Ale will always be pretty close to perfect. (Above, photograph by Jim Rees; left, courtesy of Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.)

REGULARS

.

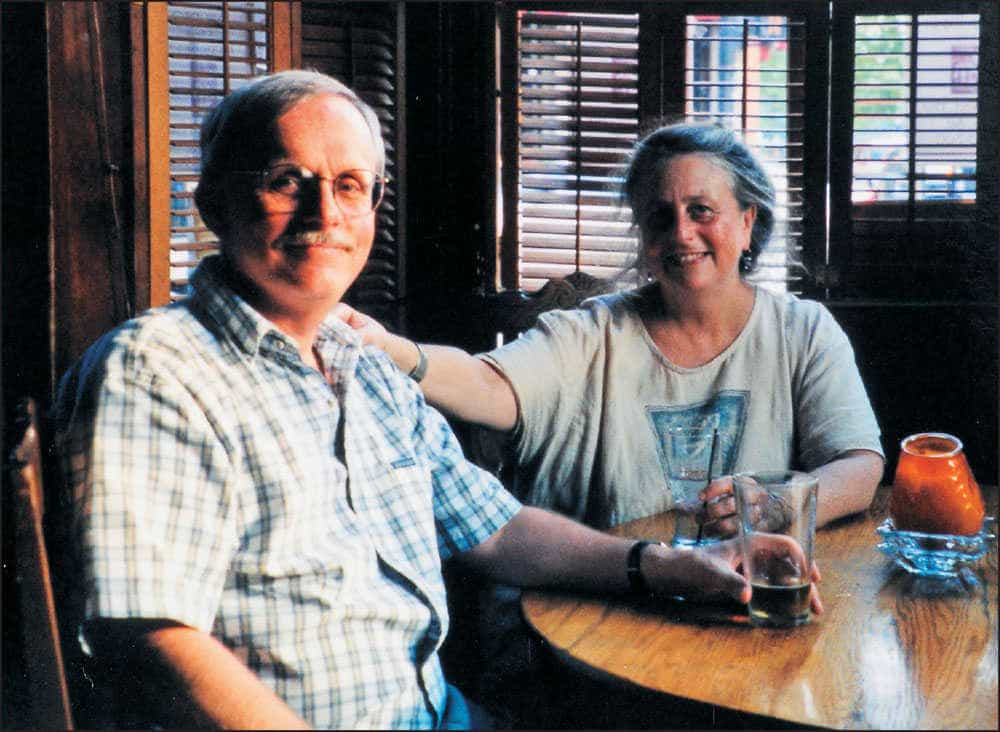

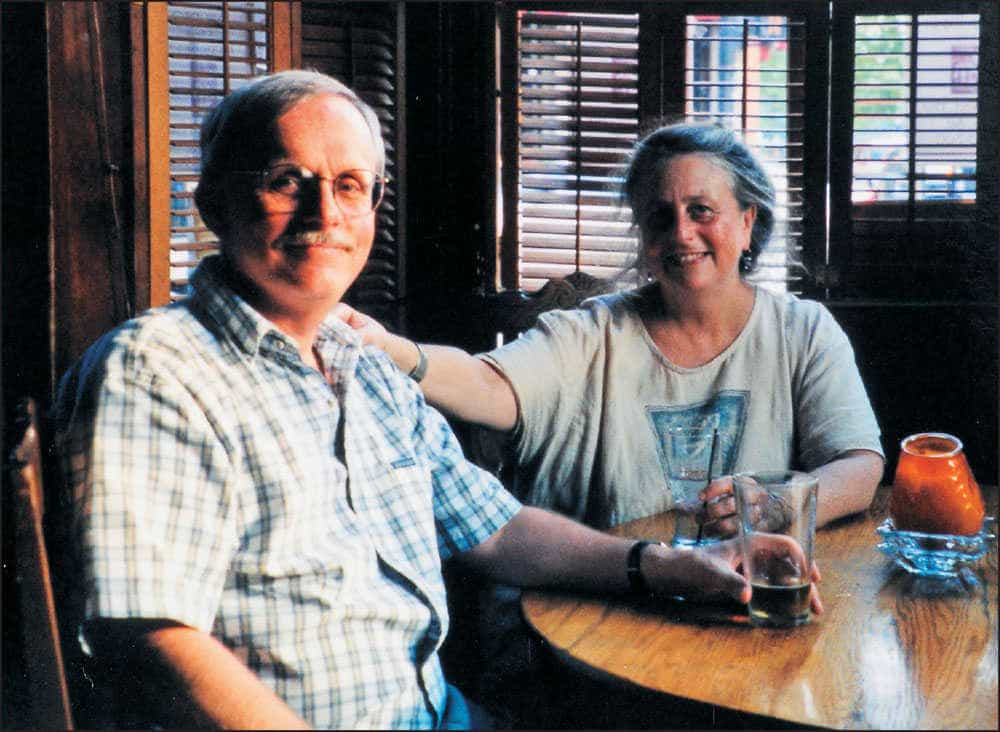

One former Del Rio waitperson remembers a night when the Colombian soccer team came in, broke glasses, and caused general mayhem. In the midst of chaos, a couple came in and quietly ordered burritos and beer. It was not until the next morning that the staff member realized the most normal part of her night had been serving Patti Smith and Fred “Sonic” Smith. Author, historian, educator, incredible source for this book, and all-around mensch Susan Wineberg and husband Lars Bjorn met at the Del Rio in 1976. She calls it “our Bicentennial romance,” and they married seven years later. Every August, they celebrated their meeting and wedding anniversary. They always made sure they got their regular big round table near the door. (Both, courtesy of Susan Wineberg and the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.)

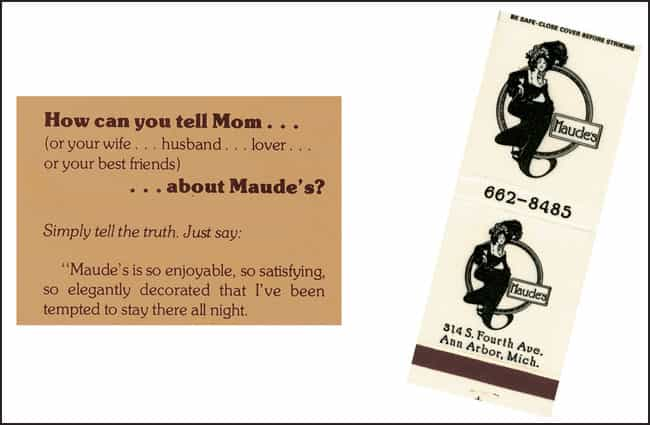

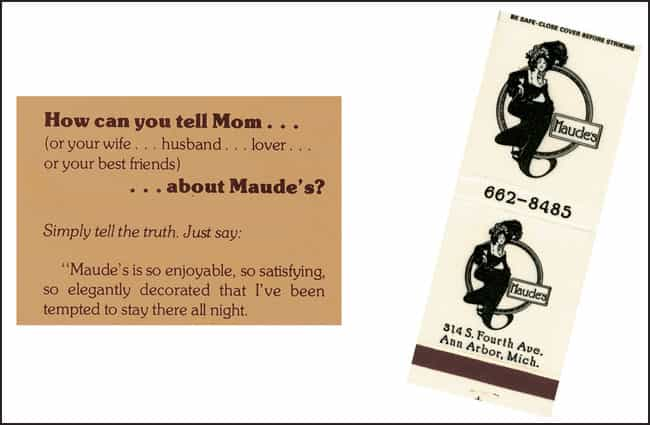

WHO

WAS

MAUDE

, ANYWAY

?

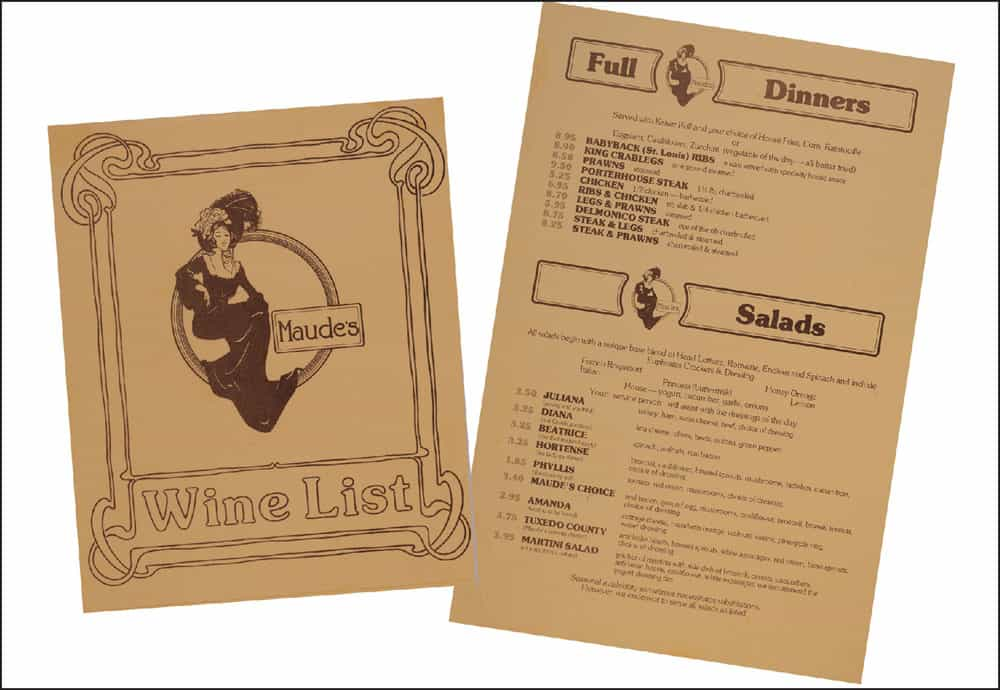

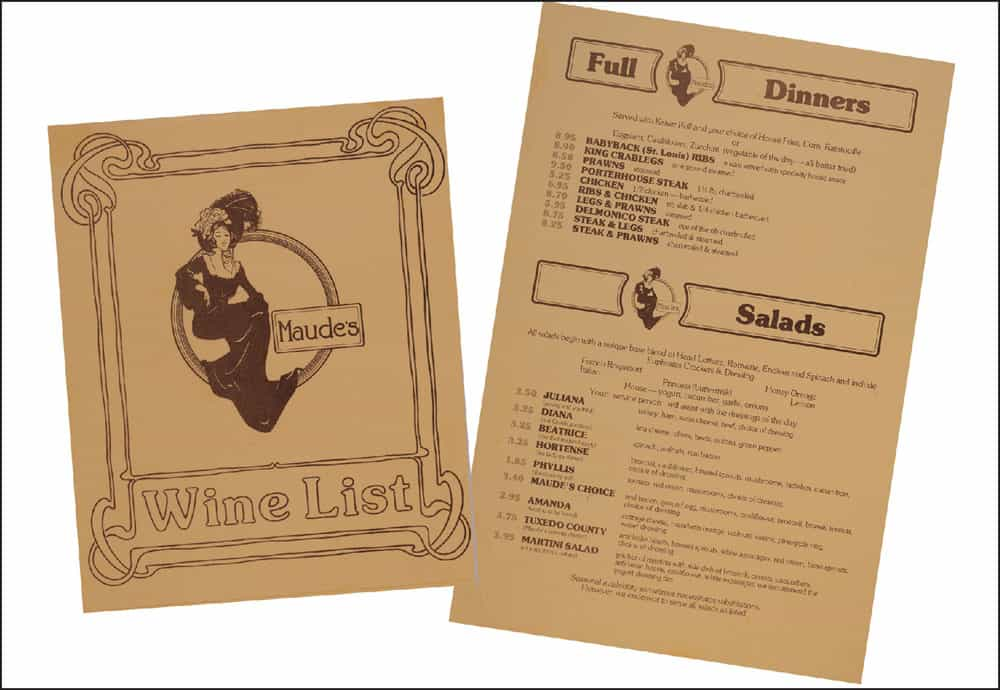

The building started as an Edsel dealership, and when beloved Maude’s opened in 1977 (in what was the Golden Falcon bar), in order to install a dishwasher, they first had to pull out a car lift cemented in the floor. Maude’s had an elegant speakeasy feel, with potted palms, leaded glass, and wrought iron. Mention Maude’s, and most people lovingly say “ribs.” To find the perfect ones, owner Dennis Serras went to the famed Montgomery Inn in Cincinnati. He learned how to cook ribs from the husband, but the wife would not give up the sauce recipe (she called it “job security”). So, after much experimenting, Maude’s developed their own sauce. Others fondly remember deep-fried vegetables, chicken with artichokes, and ice cream liquor drinks. Creative entrée-sized salads, prepared at an open salad station, included the martini salad, which was a pitcher of martinis accompanied by vegetables and dip (an early version of ranch called princess dressing). No meal was complete without the amaretto mousse—now it can be revealed that the secret to its velvety texture was marshmallow cream. Many of Maude’s cooks and waitstaff now own or work at Ann Arbor icons like Zingerman’s, Real Seafood, and others. (Both, courtesy of the JBLCA.)

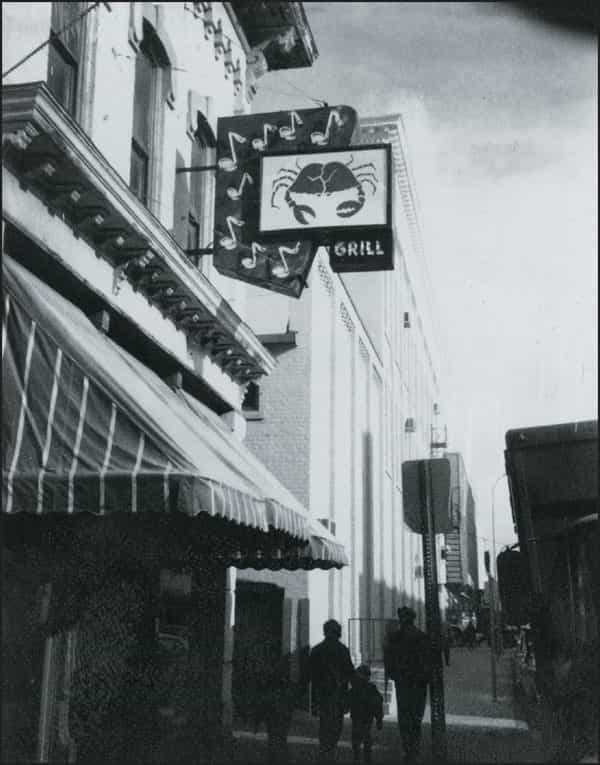

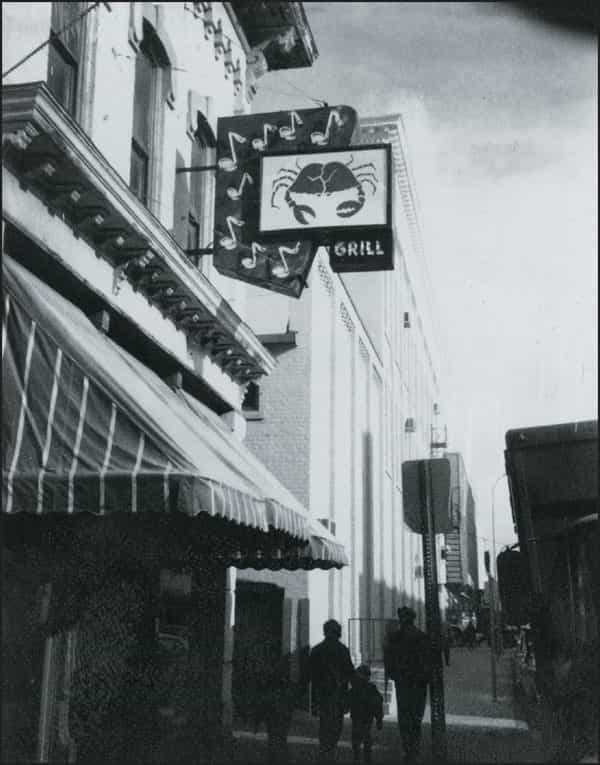

SEE

FOOD

.

Giant portions of fish and chips, spicy shrimp, great coleslaw, and Dungeness crab starred at the Cracked Crab in 1971. Quality seafood at student prices was served on paper plates. There was always a line, but no one seemed to mind. The restaurant also had a great beer list. The famous neon sign with musical notes was from the Town Bar—there was no music, they just added a crab. Closed in the mid-1990s, it is now home to Café Zola. (Courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.)

EDEN

HEALTHY

.

The roots of Eden were a natural grains and beans co-op in the Teeguarden-Leabu secondhand clothes store on State Street. It grew through various people and locations, expanding to a retail store and deli on Maynard Street in 1973. Eden Deli was one of the first places in the country to get organic and macrobiotic food. The Sun Bakery was also part of the space, as were sprout and tofu co-ops. Eden Deli had a wonderful cafeteria-style selection, with a signature chipati sandwich made from fermented whole-wheat dough filled with “monster” (Muenster) cheese, sprouts, and hummus. Although the deli closed in the late 1980s, Eden Foods went on to become one of the largest natural and organic food companies in America. (Authors’ collection.)

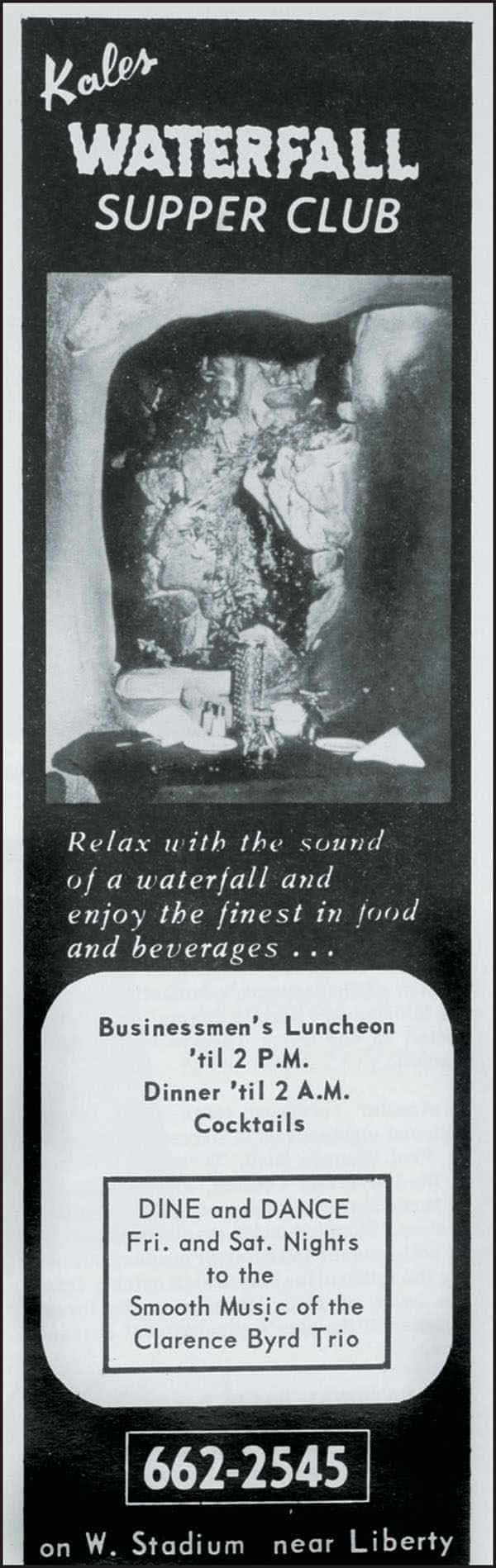

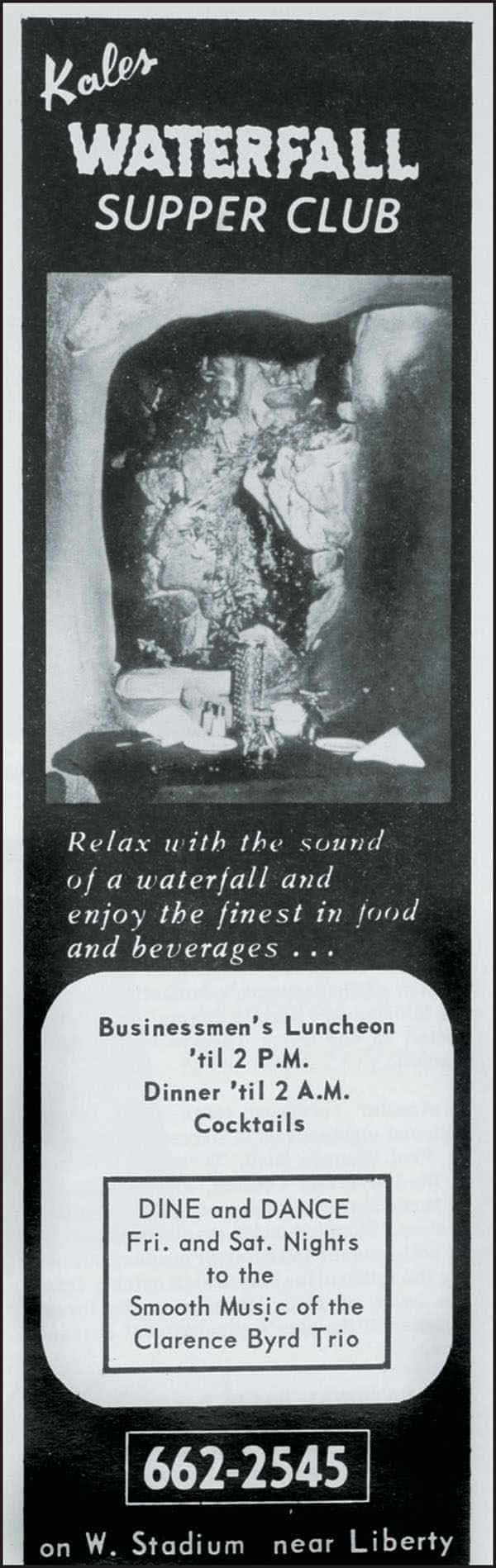

KALES

WATERFALL

.

When James Kales opened his Waterfall Restaurant in 1963, it had the appearance of something pretty much out-of-this world. Kales (with architect James H. Livingston) originally designed it to look like a giant whale. When it materialized, the place featured a 35-foot waterfall and a labyrinth of dimly lit dining “caves.” While steak and lobster were the specialties, the ambience was the star attraction. Many still recall the palpable intimacy of dining in the cavern-like culs-de-sac, the soft babble of the waterfall flowing nearby. Kales’s son Alex, a professional pianist and singer (and lifelong educator), often provided dinner music, and sometimes there was a band for dancing. Kales sold the place in 1973, but the building and waterfall remained a centerpiece for Lim’s Cantonese Restaurant and, later, Szechuan West. The building was demolished in 2011. At this writing, Jimmie Kales is 101 years old, retired, and living in Florida. (Above, authors’ collection; left, courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library.) Ann Arbor District Library.)

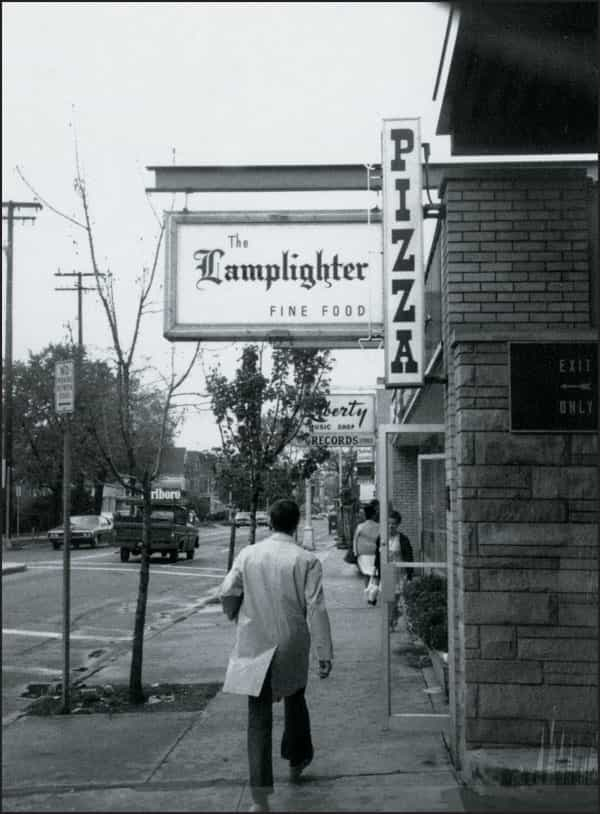

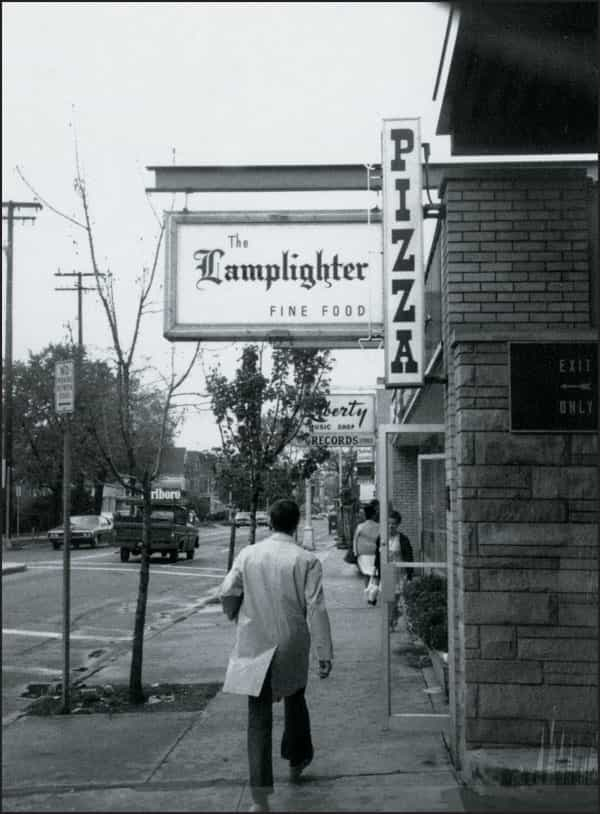

STILL

BURNS

.

The Lamplighter was a cozy place that everyone seems to miss. It had deep-dish pizza made with a chewy, sesame-topped crust—but that was just for starters. Greek specialties in a small-town diner setting made it feel extra homey. One could not help but feel intimate chatting among friends in the long, narrow, somewhat dimly lit room amid the small tables and booths, even when the place was packed. Near Liberty and Thompson Streets, the Lamplighter became a fast favorite for anyone who happened by, with some pretty heavy hitters among its fans, including Jimmy Stewart, Vincent Price, and even Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. U of M basketball teams, among other teams, ate here regularly. Pres. Gerald Ford once had to be turned away because his entourage was more than could be accommodated without displacing regular customers. (Above, photograph by Jim Rees; right, courtesy of the Ann Arbor District Library.)

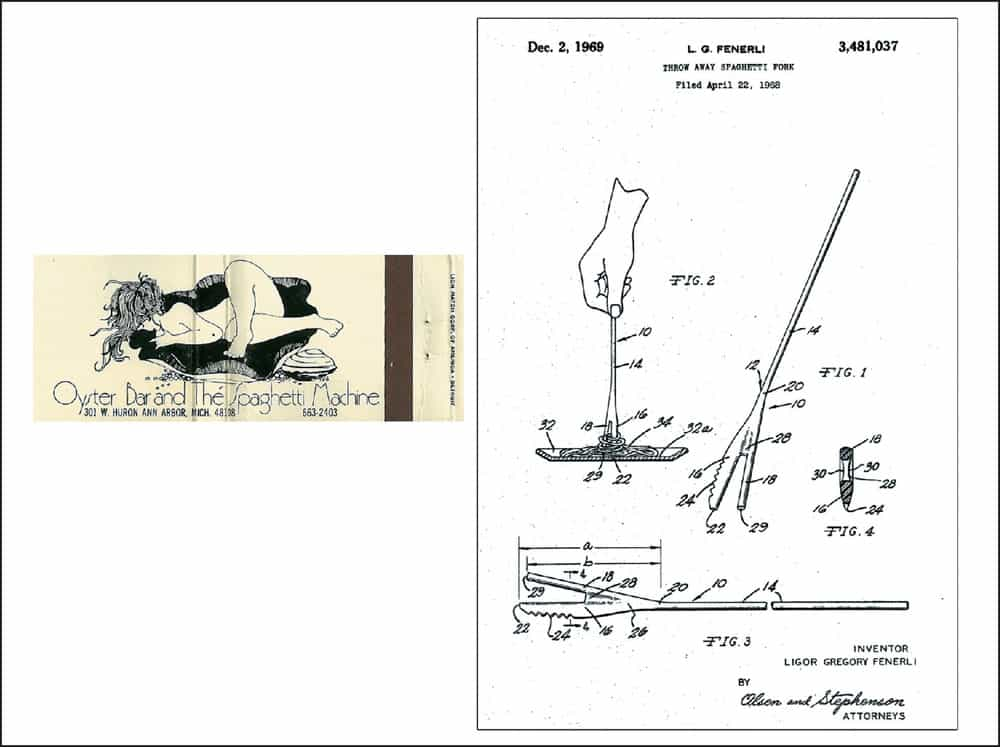

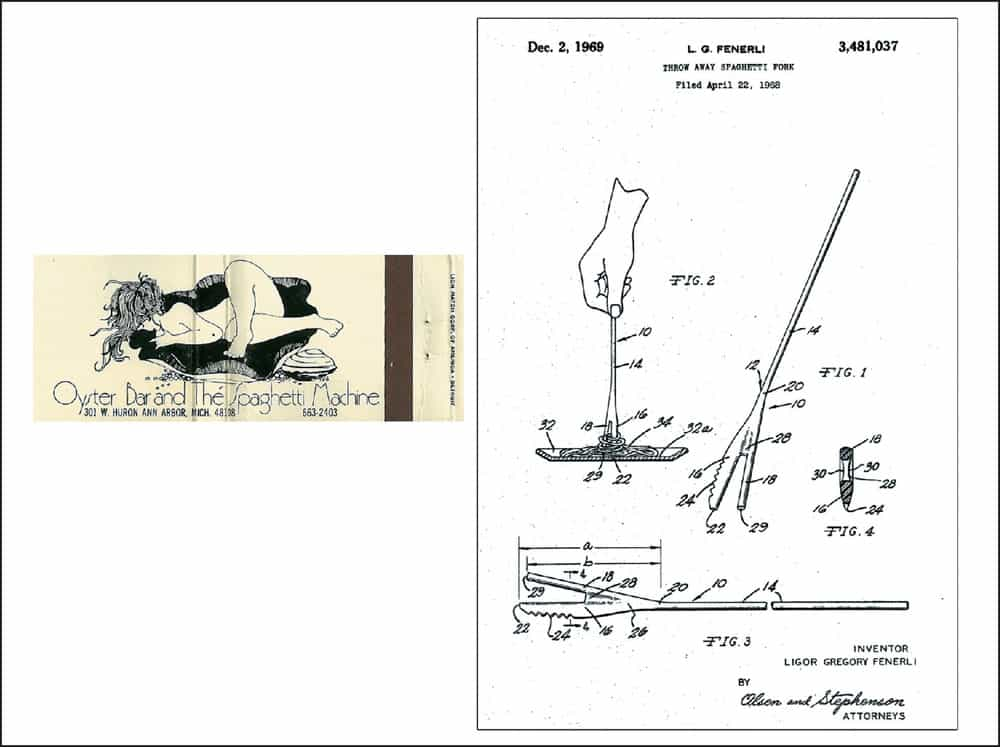

OYSTER

BAR AND

SPAGHETTI

MACHINE

.

“Fresh plants. No plastic” claims a 1974 menu. Homemade noodles at the Oyster Bar and Spaghetti Machine were a no-brainer. Local legend Greg Fenerli had a pasta-making machine for customers to watch. He even held a patent for a one-handed spaghetti fork. Diners were especially fond of the fettuccine verdi, osso bucco, and garlic salad dressing, all while listening to opera music. It was gourmet yet casual. (Authors’ collection.)

COMFORT

FOOD

.

For over 60 years, one could get blue plate specials like salmon patties, cabbage rolls, and deviled eggs at the Round Table on Huron Street, then Liberty Street. Evelyn Stack started as a waitress, then bought the place in 1966. Regulars sat at the big round table in back, poured their own coffee, and mooned over Evelyn’s homemade banana cream pie. It is said more lawsuits were settled in the Round Table than at the courthouse. (Authors’ collection.)