Naval Aircraft Designation Systems

Information for this appendix was drawn from the following sources: Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 1-3; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 46-59; and consultation with Osamu Tagaya.

The systems used by the Japanese army and navy to identify their aircraft can be extremely confusing. For the purposes of explaining how the navy identified the aircraft discussed in this study, however, only three designation systems need to be understood: the type-number system, the short-designation system, and the shi-(experimental-) number system.

TYPE-NUMBER SYSTEM

Beginning in 1921, a number was assigned to all aircraft that had been accepted for production for the Japanese navy. From 1921 through 1928, these numbers were based on the year of the current emperor’s reign. (There were only two emperors in the period covered by this study, the Taishō emperor, whose reign began in 1912, and the Shōwa emperor [the emperor Hirohito], whose reign began in 1926. In each case, the first year of reign counted as year 1.) Thus, an aircraft adopted by the navy for production in 1924 would be known as a Type 13 (thirteenth year of the reign of the Taishō emperor).

Then in 1929 the Japanese government, while not displacing the reign dates, adopted a calendar based on the supposed (but wholly mythological) founding of the Japanese state in 660 B.C. The navy implemented this system by assigning to its aircraft the last two digits of the calendar year in which the aircraft was adopted for production. Thus, according to this method of calculation, the Western calendar year 1930 was reckoned to be the Japanese year 2590, and any aircraft adopted for production in that year was identified as a Type 90. An exception to this system was made for aircraft adopted in 1940—in the Japanese calculation, 2600—which were given only a single-digit designation. Thus, the famed Mitsubishi fighter of the Pacific War was identified by the navy as the Type 0 fighter, from which is derived its Western designation, the Zero. The type-number system was the aircraft designation system most widely used at the operational level by the Japanese naval air service.

SHORT-DESIGNATION SYSTEM

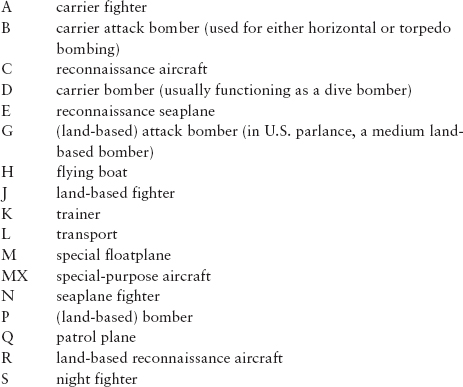

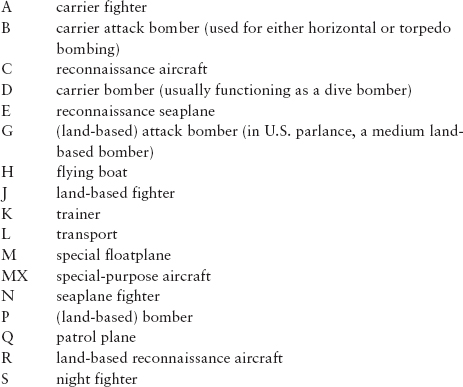

Beginning in the late 1920s, the navy introduced a designation system that identified each aircraft, once its design was fairly far advanced, by a block of symbols setting forth its category, pedigree, and status. The aircraft’s function was indicated by a letter, its “generation” by a number, its manufacturer by a letter, its model by a number, and its modification by a letter. The following explanation breaks this system down into its component parts:

1. Functional identification. This letter identified the aircraft as to its principal operational use:

A |

carrier fighter |

B |

carrier attack bomber (used for either horizontal or torpedo bombing) |

C |

reconnaissance aircraft |

D |

carrier bomber (usually functioning as a dive bomber) |

E |

reconnaissance seaplane |

G |

(land-based) attack bomber (in U.S. parlance, a medium land-based bomber) |

H |

flying boat |

J |

land-based fighter |

K |

trainer |

L |

transport |

M |

special floatplane |

MX |

special-purpose aircraft |

N |

seaplane fighter |

P |

(land-based) bomber |

Q |

patrol plane |

R |

land-based reconnaissance aircraft |

S |

night fighter |

2. Generation identification. This number simply indicated the place of the aircraft in the chronology of production of naval aircraft of a similar function.

3. Manufacturer’s identification. This letter identified the aircraft firm that designed the aircraft and was usually its principal producer. The following letters represent the principal manufacturers of aircraft described in this study: A = Aichi; H = Hirō; K = Kawanishi; M = Mitsubishi; N = Nakajima; Y = Yokosuka.

4. Model identification. This number indicated the particular design configuration of an aircraft. As significant changes or improvements were made in the aircraft, the model number would be changed upward.

5. Modification identification. Minor changes in the design or construction of an aircraft not justifying a change in the model number would be indicated by a letter in Japanese phonetic spelling (equating to the English a, b, c, etc.) following the model number.

In rare cases when an aircraft used for a particular operational function was adapted for use in an entirely different function, a letter drawn from the functional list would be appended after the model number or the modification letter.

Putting all these symbols together, the following short designation identifies a particular model of the famed Mitsubishi fighter aircraft of the Pacific War:

Shi- (EXPERIMENTAL-) NUMBER SYSTEM

As explained in the text, every specific aircraft design in the Japanese navy began its life as a set of required specifications set forth by the Navy General Staff and released to aircraft manufacturers interested in bidding for the contract to design and produce it. Beginning in 1931, the navy initiated a system that identified as “experimental” each projected aircraft whose design was still being let for bid or that was still in the prototype stage. It was, in effect, a temporary identification similar to the “X” and “Y” designations used in the United States for aircraft in preliminary stages of development.

This shi (experimental) number was based upon the reign date of the Shōwa emperor. Thus, an aircraft projected by the navy in 1937 was given a 12-shi number (twelfth year of Shōwa), and an aircraft let out for bid in 1940 would be designated a 15-shi (fifteenth year of Shōwa). To tell apart various naval aircraft that had been planned in the same year, each aircraft was also identified under this system by a functional designation. Thus, the famed Mitsubishi fighter plane of the Pacific War was initially identified as a 12-shi carrier fighter.

In addition to these three systems, beginning in 1943 the Japanese navy began officially assigning more popular names to its aircraft in lieu of type numbers. These were poetic in nature and represented various meteorological or natural phenomena. For example, as briefly mentioned in the text, the fighter aircraft that was supposed to succeed the Zero was called the Shiden—“Violet Lightning.”

Finally, mention should be made of the designation system with which Americans are most familiar, the Pacific code-name system. Initiated in 1942 by the Allied Air Forces Directorate of Intelligence, Southwest Pacific Area, this system used personal names, either male or female, to identify Japanese aircraft. Fighters and reconnaissance seaplanes were given male names and bombers, attack bombers, dive bombers, all reconnaissance aircraft, and flying boats were given female names. In the postwar decades, however, American writers on the Pacific War have tended to use the Pacific code-name system overwhelmingly without acknowledgment that it was entirely alien to any Japanese terminological concepts during the war. Western studies that have eschewed the use of these artificial names have tended, like this study, to use the short-designation system, which combines the merits of simplicity and accuracy. But it should be recognized that during the war the Japanese navy, which most commonly used the type-number system in its records of operations, gave the short-designation system only a narrow and highly technical application.