WHAT’S IN THIS CHAPTER?

WROX.COM CODE DOWNLOADS FOR THIS CHAPTER

Please note that all the code examples in this chapter are available as a part of this chapter’s code download on the book’s website at www.wrox.com on the Download Code tab.

The progression from Active Server Pages 3.0 to ASP.NET 1.0 was revolutionary, to say the least. And now the revolution continues with the latest release of ASP.NET — version 4.5. The original introduction of ASP.NET 1.0 fundamentally changed the way websites and applications were developed. ASP.NET 4.5 is just as revolutionary in the way it will increase your productivity. As of late, the primary goal of ASP.NET is to enable you to build powerful, secure, dynamic applications using the least possible amount of code. Although this book covers the new features provided by ASP.NET 4.5, it also covers all the offerings of ASP.NET technology.

If you are new to ASP.NET and building your first set of applications in ASP.NET 4.5, you may be amazed by the vast amount of server controls it provides. You may marvel at how it enables you to work with data more effectively using a series of data providers. You may be impressed at how easily you can build in security and personalization.

The outstanding capabilities of ASP.NET 4.5 do not end there, however. This chapter looks at many options that facilitate working with ASP.NET web pages and applications. One of the first steps you, the developer, should take when starting a project is to become familiar with the foundation you are building on and the options available for customizing that foundation.

With ASP.NET 4.5, you have the option — using Visual Studio 2012 — to create an application with a virtual directory mapped to IIS or a standalone application outside the confines of IIS. Whereas the early Visual Studio .NET 2002/2003 IDEs forced developers to use IIS for all web applications, Visual Studio 2008/2010 (and Visual Web Developer 2008/2010 Express Edition, for that matter) included a built-in web server, known as Cassini, that you used for development, much like the one used in the past with the ASP.NET WebMatrix. In Visual Studio 2012, the built-in web server is IIS Express.

The following section shows you how to use IIS Express, which comes with Visual Studio 2012.

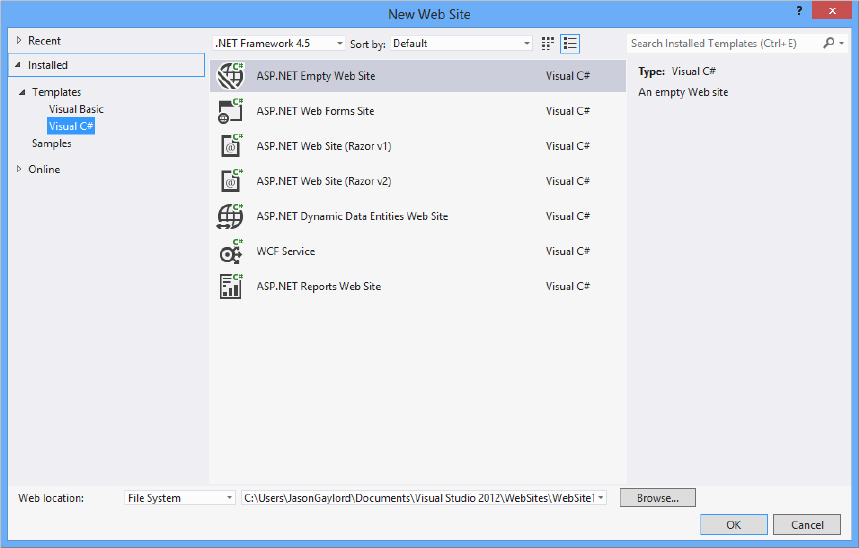

By default, Visual Studio 2012 builds applications by using IIS Express. You can see this when you select File ⇒ New ⇒ Web Site in the IDE. By default, the location provided for your application is in C:\Users\JasonGaylord\Documents\Visual Studio 2012\WebSites if you are using Windows 8 (shown in Figure 3-1). It is not C:\Inetpub\wwwroot\ as it would have been in Visual Studio .NET 2002/2003. By default, any site that you build and host inside C:\Users\JasonGaylord\Documents\Visual Studio 2012\WebSites (or any other folder you create) uses IIS Express, which is built into Visual Studio 2012. If you use the built-in web server from Visual Studio 2012, you are not locked into the WebSites folder. Rather, you can create and use any folder you like.

To change from this default, you have a handful of options. Click the Browse button in the New Web Site dialog box. The Choose Location dialog box opens, shown in Figure 3-2.

If you continue to use the built-in IIS Express that Visual Studio 2012 provides, you can choose a new location for your website from this dialog box. To choose a new location, select a new folder and save your .aspx pages and any other associated files to this directory. When using Visual Studio 2012, you can run your application completely from this location. This way of working with the ASP.NET pages you create is ideal if you do not have access to a web server because it enables you to build applications that do not reside on a machine with the full version of IIS.

After you create the new website, you have access to modify the IIS Express settings right in the Visual Studio properties pane. An example of this is shown in Figure 3-3.

From the Choose Location dialog box (as shown in Figure 3-4), you can also change where your application is saved and which type of web server your application employs. To use IIS, select the Local IIS button in the dialog box. This changes the results in the text area to show you a list of all the virtual application roots on your machine.

To create a new virtual root for your application, highlight Default Web Site. Two accessible buttons appear at the top of the dialog box (see Figure 3-4). When you look from left to right, the first button in the upper-right corner of the dialog box is for creating a new site. This is used for adding new sites to IIS Express. The second button is for creating a new web application — or a virtual root. The third button enables you to create virtual directories for any of the virtual roots you created. The last button is a Delete button, which allows you to delete any selected sites, virtual directories, or virtual roots.

After you have created the virtual directory you want, click the Open button. Visual Studio 2012 then goes through the standard process to create your application. Now, however, instead of depending on IIS Express, your application will use the full version of IIS. When you invoke your application, the URL consists of something like http://localhost/MyWeb/Default.aspx, which means it is using IIS.

Not only can you decide on the type of web server for your web application when you create it using the Choose Location dialog box, but you can also decide where your application is going to be located. With the previous options, you built applications that resided on your local server. The FTP option enables you to actually store and even code your applications while they reside on a server somewhere else in your enterprise — or on the other side of the planet. You can also use the FTP capabilities to work on different locations within the same server. Using this capability provides a wide range of possible options. You can see this in Figure 3-5.

To create your application on a remote server using FTP, simply provide the server name, the port to use, and the directory — as well as any required credentials. If the correct information is provided, Visual Studio 2012 reaches out to the remote server and creates the appropriate files for the start of your application, just as if it were doing the job locally. From this point on, you can open your project and connect to the remote server using FTP.

ASP.NET provides two paths for structuring the code of your ASP.NET pages. The first path utilizes the code-inline model. This model should be familiar to classic ASP developers because all the code is contained within a single .aspx page. The second path uses ASP.NET’s code-behind model, which allows for code separation of the page’s business logic from its presentation logic. In this model, the presentation logic for the page is stored in an .aspx page, whereas the logic piece is stored in a separate class file: .aspx.vb or .aspx.cs. Using the code-behind model is considered the best practice because it provides a clean model in separation of pure UI elements from code that manipulates these elements. It is also seen as a better means in maintaining code.

With the .NET Framework 1.0/1.1, developers went out of their way (and outside Visual Studio .NET) to build their ASP.NET pages inline and avoid the code-behind model that was so heavily promoted by Microsoft and others. Visual Studio 2012 (as well as Visual Studio Express 2012 for Web) allows you to build your pages easily using this coding style. To build an ASP.NET page inline instead of using the code-behind model, you simply select the page type from the Add New Item dialog box and make sure that the Place Code in Separate File check box is not selected. You can get at this dialog box (see Figure 3-6) by right-clicking the project or the solution in the Solution Explorer and selecting Add New Item.

From here, you can see the check box you need to unselect if you want to build your ASP.NET pages inline. In fact, many page types have options for both inline and code-behind styles. Table 3-1 shows your inline options when selecting files from this dialog box.

| OPTION | FILE CREATED |

| Web Form | .aspx file |

| Master Page | .master file |

| Web User Control | .ascx file |

| Web Service | .asmx file |

By using the Web Form option with a few controls, you get a page that encapsulates not only the presentation logic, but the business logic as well. This is illustrated in Listing 3-1 (Listing03-01.aspx in this chapter’s code download).

LISTING 3-1: A simple page that uses the inline coding model

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<script runat="server">

Protected Sub Button1_Click(sender As Object, e As EventArgs)

Literal1.Text = "Hello " & TextBox1.Text

End Sub

</script>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head runat="server">

<title>Simple Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">

<div>

What is your name?<br />

<asp:TextBox ID="TextBox1" runat="server"></asp:TextBox>

<asp:Button ID="Button1" runat="server" Text="Submit"

OnClick="Button1_Click" />

</div>

<div>

<asp:Literal ID="Literal1" runat="server" />

</div>

</form>

</body>

</html>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<script runat="server">

protected void Button1_Click1(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Literal1.Text = "Hello " + TextBox1.Text;

}

</script>From this example, you can see that all the business logic is encapsulated in between <script> tags. The nice feature of the inline model is that the business logic and the presentation logic are contained within the same file. Some developers find that having everything in a single viewable instance makes working with the ASP.NET page easier. Another great thing is that Visual Studio 2012 provides IntelliSense when working with the inline coding model and ASP.NET 4.5. Before Visual Studio 2005, this capability did not exist.

The other option for constructing your ASP.NET 4.5 pages is to build your files using the code-behind model. The idea of using the code-behind model is to separate the business logic and presentation logic into separate files. Doing this makes working with your pages easier, especially if you are working in a team environment where visual designers work on the UI of the page and coders work on the business logic that sits behind the presentation pieces.

To create a new page in your ASP.NET solution that uses the code-behind model, select the page type you want from the New File dialog box. To build a page that uses the code-behind model, you first select the page in the Add New Item dialog box and make sure the Place Code in Separate File check box is selected. Table 3-2 shows you the options for pages that use the code-behind model.

| FILE OPTION | FILE CREATED |

| Web Form | .aspx file; .aspx.vb or .aspx.cs file |

| Master Page | .master file; .master.vb or .master.cs file |

| Web User Control | .ascx file; .ascx.vb or .ascx.cs file |

| Web Service | .asmx file; .vb or .cs file |

In Listing 3-1, you saw how to create a page using the inline coding style. In Listings 3-2 and 3-3, you see how to convert the inline model to the code-behind model. You can find the code for Listing 3-2 as Listing03-02.aspx in this chapter’s download. You can find the code for Listing 3-3 in this chapter’s download as Listing03-02.aspx.vb and Listing03-02.aspx.cs.

LISTING 3-2: An .aspx page that uses the ASP.NET 4.5 code-behind model

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" AutoEventWireup="false" CodeBehind="Listing03-02.aspx.vb"

Inherits="ProfessionalASPNet45_03VB.Listing03_02" %>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head id="Head1" runat="server">

<title>Simple Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">

<div>

What is your name?<br />

<asp:TextBox ID="TextBox1" runat="server"></asp:TextBox>

<asp:Button ID="Button1" runat="server" Text="Submit"

OnClick="Button1_Click" />

</div>

<div>

<asp:Literal ID="Literal1" runat="server" />

</div>

</form>

</body>

</html>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true" CodeBehind="Listing03-02.aspx.cs"

Inherits="ProfessionalASPNet45_03CS.Listing03_02" %>LISTING 3-3: A code-behind page

VB

Partial Public Class Listing03_02

Inherits System.Web.UI.Page

Protected Sub Button1_Click(sender As Object, e As EventArgs)

Literal1.Text = "Hello " & TextBox1.Text

End Sub

End ClassC#

public partial class Listing03_02 : System.Web.UI.Page

{

protected void Button1_Click1(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Literal1.Text = "Hello " + TextBox1.Text;

}

}

The .aspx page using this ASP.NET code-behind model has some attributes in the Page directive that you should pay attention to when working in this mode. The first attribute needed for the code-behind model to work is the CodeBehind attribute. This attribute in the Page directive is meant to point to the code-behind page that is used with this presentation page. In this case, the value assigned is Listing03-02.aspx.vb or Listing03-02.aspx.cs. The second attribute needed is the Inherits attribute. This attribute was available in previous versions of ASP.NET, but was little used before ASP.NET 2.0. This attribute specifies the name of the class that is bound to the page when the page is compiled. The directives are simple enough in ASP.NET 4.5. Look at the code-behind page from Listing 3-3.

The code-behind page is rather simple in appearance because of the partial class capabilities that .NET 4.5 provides. You can see that the class created in the code-behind file uses partial classes, employing the Partial keyword in Visual Basic 2012 and the partial keyword from C# 2012. This enables you to simply place the methods that you need in your page class. In this case, you have a button-click event and nothing else.

Later in this chapter, you look at the compilation process for both of these models.

ASP.NET directives are part of every ASP.NET page. You can control the behavior of your ASP.NET pages by using these directives. Here is an example of the Page directive:

<%@ Page Language="vb" AutoEventWireup="false" CodeBehind="Listing03-02.aspx.vb"

Inherits="ProfessionalASPNet45_03VB.Listing03_02" %>Twelve directives, shown in Table 3-3, are at your disposal in your ASP.NET pages or user controls. You use these directives in your applications whether the page uses the code-behind model or the inline coding model.

| DIRECTIVE | DESCRIPTION |

| @Assembly | Links an assembly to the page or user control for which it is associated. |

| @Control | Page directive meant for use with user controls (.ascx). |

| @Implements | Implements a specified .NET Framework interface. |

| @Import | Imports specified namespaces into the page or user control. |

| @Master | Enables you to specify master page–specific attributes and values to use when the page parses or compiles. This directive can be used only with master pages (.master). |

| @MasterType | Associates a class name to a page to get at strongly typed references or members contained within the specified master page. |

| @OutputCache | Controls the output caching policies of a page or user control. |

| @Page | Enables you to specify page–specific attributes and values to use when the page parses or compiles. This directive can be used only with ASP.NET pages (.aspx). |

| @PreviousPageType | Enables an ASP.NET page to work with a postback from another page in the application. |

| @Reference | Links a page or user control to the current page or user control. |

| @Register | Associates aliases with namespaces and class names for notation in the custom server control syntax. |

| @WebHandler | Enables a page to be used as an HttpHandler. This will be covered more in Chapter 30. |

Basically, these directives are commands that the compiler uses when the page is compiled. Directives are simple to incorporate into your pages. A directive is written in the following format:

<%@ [Directive] [Attribute=Value] %>From this, you can see that a directive is opened with a <%@ and closed with a %>. Putting these directives at the top of your pages or controls is best because this is traditionally where developers expect to see them (although the page still compiles if the directives are located at a different place). Of course, you can also add more than a single attribute to your directive statements, as shown in the following:

<%@ [Directive] [Attribute=Value] [Attribute=Value] %>The following sections provide a quick review of each of these directives. Some of these directives are valid only within specific page types.

The @Page directive enables you to specify attributes and values for an ASP.NET page (.aspx) to be used when the page is parsed or compiled. This is the most frequently used directive from Table 3-3. Because the ASP.NET page is such an important part of ASP.NET, there are quite a few attributes for the directive. Table 3-4 summarizes the attributes available through the @Page directive.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| AspCompat | Permits the page to be executed on a single-threaded apartment thread when given a value of True. The default setting for this attribute is False. |

| Async | Specifies whether the ASP.NET page is processed synchronously or asynchronously. |

| AsyncTimeout | Specifies the amount of time in seconds to wait for the asynchronous task to complete. The default setting is 45 seconds. |

| AutoEventWireup | Specifies whether the page events are autowired when set to True. The default setting for this attribute is True. |

| Buffer | Enables HTTP response buffering when set to True. The default setting for this attribute is True. |

| ClassName | Specifies the name of the class that is bound to the page when the page is compiled. |

| ClientIDMode | Specifies the algorithm that the page should use when generating ClientID values for server controls that are on the page. The default value is AutoID (the mode that was used for ASP.NET pages prior to ASP.NET 4). |

| ClientTarget | Specifies the target user agent a control should render content for. This attribute needs to be tied to an alias defined in the <clientTarget> section of the web.config file. |

| CodeBehind | References the compiled code-behind file with which the page is associated. This attribute is used for web application projects. |

| CodeFile | References the code-behind file with which the page is associated. This attribute is used for website projects. |

| CodeFileBaseClass | Specifies the type name of the base class to use with the code-behind class, which is used by the CodeFile attribute. |

| CodePage | Indicates the code page value for the response. |

| CompilationMode | Specifies whether ASP.NET should compile the page or not. The available options include Always (the default), Auto, or Never. A setting of Auto means that if possible, ASP.NET will not compile the page. |

| CompilerOptions | Compiler string that indicates compilation options for the page. |

| ContentType | Defines the HTTP content type of the response as a standard MIME type. |

| Culture | Specifies the culture setting of the page. ASP.NET 3.5 and later include the capability to give the Culture attribute a value of Auto to enable automatic detection of the culture required. |

| Debug | Compiles the page with debug symbols in place when set to True. |

| Description | Provides a text description of the page. The ASP.NET parser ignores this attribute and its assigned value. |

| EnableEventValidation | Specifies whether to enable validation of events in postback and callback scenarios. The default setting of True means that events will be validated. |

| EnableSessionState | Session state for the page is enabled when set to True. The default setting is True. |

| EnableTheming | Page is enabled to use theming when set to True. The default setting for this attribute is True. |

| EnableViewState | ViewState is maintained across the page when set to True. The default value is True. |

| EnableViewStateMac | Page runs a machine-authentication check on the page’s ViewState when the page is posted back from the user when set to True. The default value is False. |

| ErrorPage | Specifies a URL to post to for all unhandled page exceptions. |

| Explicit | Visual Basic Explicit option is enabled when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| Language | Defines the language being used for any inline rendering and script blocks. |

| LCID | Defines the locale identifier for the web form’s page. |

| LinePragmas | Boolean value that specifies whether line pragmas are used with the resulting assembly. |

| MasterPageFile | Takes a String value that points to the location of the master page used with the page. This attribute is used with content pages. |

| MaintainScrollPositionOnPostback | Takes a Boolean value, which indicates whether the page should be positioned exactly in the same scroll position or whether the page should be regenerated in the uppermost position for when the page is posted back to itself. |

| MetaDescription | Allows you to specify a page’s description in a Meta tag for SEO purposes. |

| MetaKeywords | Allows you to specify a page’s keywords in a Meta tag for SEO purposes. |

| ResponseEncoding | Specifies the response encoding of the page content. |

| SmartNavigation | Specifies whether to activate the ASP.NET Smart Navigation feature for richer browsers. This returns the postback to the current position on the page. The default value is False. Since ASP.NET 2.0, SmartNavigation has been deprecated. Use the SetFocus() method and the MaintainScrollPositionOnPostback property instead. |

| Src | Points to the source file of the class used for the code-behind of the page being rendered. |

| Strict | Compiles the page using the Visual Basic Strict mode when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| StylesheetTheme | Applies the specified theme to the page using the ASP.NET themes feature. The difference between the StylesheetTheme and Theme attributes is that StylesheetTheme will not override preexisting style settings in the controls, whereas Theme will remove these settings. |

| Theme | Applies the specified theme to the page using the ASP.NET themes feature. |

| Title | Applies a page’s title. This is an attribute mainly meant for content pages that must apply a page title other than what is specified in the master page. |

| Trace | Page tracing is enabled when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| TraceMode | Specifies how the trace messages are displayed when tracing is enabled. The settings for this attribute include SortByTime or SortByCategory. The default setting is SortByTime. |

| Transaction | Specifies whether transactions are supported on the page. The settings for this attribute are Disabled, NotSupported, Supported, Required, and RequiresNew. The default setting is Disabled. |

| UICulture | The value of the UICulture attribute specifies what UI Culture to use for the ASP.NET page. ASP.NET 3.5 and later include the capability to give the UICulture attribute a value of Auto to enable automatic detection of the UICulture. |

| ValidateRequest | When this attribute is set to True, the form input values are checked against a list of potentially dangerous values. This helps protect your web application from harmful attacks such as JavaScript attacks. The default value is True. |

| ViewStateEncryptionMode | Specifies how the ViewState is encrypted on the page. The options include Auto, Always, and Never. The default is Auto. |

| ViewStateMode | Determines whether the ViewState is maintained for controls on a page. |

| WarningLevel | Specifies the compiler warning level at which to stop compilation of the page. Possible values are 0 through 4. |

Here is an example of how to use the @Page directive:

<%@ Page Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true" CodeBehind="Listing03-02.aspx.cs"

Inherits="ProfessionalASPNet45_03CS.Listing03_02" %>The @Master directive is quite similar to the @Page directive except that the @Master directive is meant for master pages (.master). In using the @Master directive, you specify properties of the templated page that you will be using in conjunction with any number of content pages on your site. Any content pages (built using the @Page directive) can then inherit from the master page all the master content (defined in the master page using the @Master directive). Although they are similar, the @Master directive has fewer attributes available to it than does the @Page directive. The available attributes for the @Master directive are shown in Table 3-5.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| AutoEventWireup | Specifies whether the master page’s events are autowired when set to True. The default setting is True. |

| ClassName | Specifies the name of the class that is bound to the master page when compiled. |

| CodeBehind | References the compiled code-behind file with which the master page is associated. |

| CodeFile | References the code-behind file with which the master page is associated. |

| CompilationMode | Specifies whether ASP.NET should compile the page. The available options include Always (the default), Auto, or Never. A setting of Auto means that if possible, ASP.NET will not compile the page. |

| CompilerOptions | Compiler string that indicates compilation options for the master page. |

| Debug | Compiles the master page with debug symbols in place when set to True. |

| Description | Provides a text description of the master page. The ASP.NET parser ignores this attribute and its assigned value. |

| EnableTheming | Indicates the master page is enabled to use theming when set to True. The default setting for this attribute is True. |

| EnableViewState | Maintains the ViewState for the master page when set to True. The default value is True. |

| Explicit | Indicates that the Visual Basic Explicit option is enabled when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| Inherits | Specifies the CodeBehind class for the master page to inherit. |

| Language | Defines the language that is being used for any inline rendering and script blocks. |

| LinePragmas | Boolean value that specifies whether line pragmas are used with the resulting assembly. |

| MasterPageFile | Takes a String value that points to the location of the master page used with the master page. It is possible to have a master page use another master page, which creates a nested master page. |

| Src | Points to the source file of the class used for the code-behind of the master page being rendered. |

| Strict | Compiles the master page using the Visual Basic Strict mode when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| WarningLevel | Specifies the compiler warning level at which you want to abort compilation of the page. Possible values are from 0 to 4. |

Here is an example of how to use the @Master directive:

<%@ Master Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true"

CodeBehind="ProfessionalASPNet45-Layout.master.cs"

Inherits="ProfessionalASPNet45_03CS.ProfessionalASPNet45_Layout" %>The @Control directive is similar to the @Page directive except that you use it when you build an ASP.NET user control. The @Control directive allows you to define the properties to be inherited by the user control. These values are assigned to the user control as the page is parsed and compiled. The available attributes are fewer than those of the @Page directive, but they allow for the modifications you need when building user controls. Table 3-6 details the available attributes.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| AutoEventWireup | Specifies whether the user control’s events are autowired when set to True. The default setting is True. |

| ClassName | Specifies the name of the class that is bound to the user control when the page is compiled. |

| ClientIDMode | Specifies the algorithm that the page should use when generating ClientID values for server controls that are on the page. The default value is AutoID (the mode that was used for ASP.NET pages prior to ASP.NET 4). |

| CodeBehind | References the compiled code-behind file with which the master page is associated. In ASP.NET 2.0 or earlier, CodeFile should be used along with Inherits. |

| CodeFile | References the code-behind file with which the user control is associated. |

| CodeFileBaseClass | Specifies the type name of the base class to use with the code-behind class, which is used by the CodeFile attribute. |

| CompilationMode | Specifies whether the control should be compiled. |

| CompilerOptions | Compiler string that indicates compilation options for the user control. |

| Debug | Compiles the user control with debug symbols in place when set to True. |

| Description | Provides a text description of the user control. The ASP.NET parser ignores this attribute and its assigned value. |

| EnableTheming | User control is enabled to use theming when set to True. The default setting for this attribute is True. |

| EnableViewState | ViewState is maintained for the user control when set to True. The default value is True. |

| Explicit | Visual Basic Explicit option is enabled when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| Inherits | Specifies the CodeBehind class for the user control to inherit. |

| Language | Defines the language used for any inline rendering and script blocks. |

| LinePragmas | Boolean value that specifies whether line pragmas are used with the resulting assembly. |

| Src | Points to the source file of the class used for the code-behind of the user control being rendered. |

| Strict | Compiles the user control using the Visual Basic Strict mode when set to True. The default setting is False. |

| WarningLevel | Specifies the compiler warning level at which to stop compilation of the user control. Possible values are 0 through 4. |

The @Control directive is meant to be used with an ASP.NET user control. The following is an example of how to use the directive:

<%@ Control Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true"

CodeBehind="RegistrationUserControl.ascx.cs"

Inherits="ProfessionalASPNet45_03CS.RegistrationUserControl" %The @Import directive allows you to specify a namespace to be imported into the ASP.NET page or user control. By importing, all the classes and interfaces of the namespace are made available to the page or user control. This directive supports only a single attribute: Namespace.

The Namespace attribute takes a String value that specifies the namespace to be imported. The @Import directive cannot contain more than one attribute/value pair. Because of this, you must place multiple namespace imports in multiple lines as shown in the following example:

<%@ Import Namespace="System.Data" %>

<%@ Import Namespace="System.Data.SqlClient" %>Several assemblies are already being referenced by your application. You can find a list of these imported namespaces by looking in the root web.config file found at C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.xxxxx\Config. You can find this list of assemblies being referenced from the <assemblies> child element of the <compilation> element. The settings in the root web.config file are as follows:

<assemblies>

<add assembly="Microsoft.VisualStudio.Web.PageInspector.Loader,

Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="mscorlib" />

<add assembly="Microsoft.CSharp, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="System, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.Configuration, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="System.Web, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="System.Data, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.Web.Services, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="System.Xml, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.Drawing, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="System.EnterpriseServices, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b03f5f7f11d50a3a" />

<add assembly="System.IdentityModel, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.Runtime.Serialization, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.ServiceModel, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.ServiceModel.Activation, Version=4.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.ServiceModel.Web, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.Activities, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.ServiceModel.Activities, Version=4.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.WorkflowServices, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.Core, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.Web.Extensions, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.Data.DataSetExtensions, Version=4.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.Xml.Linq, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089" />

<add assembly="System.ComponentModel.DataAnnotations, Version=4.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.Web.DynamicData, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.Web.ApplicationServices, Version=4.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="*" />

<add assembly="System.Web.WebPages.Deployment, Version=1.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add assembly="System.Web.WebPages.Deployment, Version=2.0.0.0,

Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

</assemblies>Because of this reference in the root web.config file, these assemblies do not need to be referenced in the References folder, as you would have done in ASP.NET 1.0/1.1. You can actually add or delete assemblies that are referenced from this list. For example, if you have a custom assembly referenced continuously by every application on the server, you can simply add a similar reference to your custom assembly next to these others. You can perform this same task through the application-specific web.config file of your application as well.

Even though assemblies might be referenced, you must still import the namespaces of these assemblies into your pages. The same root web.config file contains a list of namespaces automatically imported into every page of your application. This is specified through the <namespaces> child element of the <pages> element.

<namespaces>

<add namespace="System" />

<add namespace="System.Collections" />

<add namespace="System.Collections.Generic" />

<add namespace="System.Collections.Specialized" />

<add namespace="System.ComponentModel.DataAnnotations" />

<add namespace="System.Configuration" />

<add namespace="System.Linq" />

<add namespace="System.Text" />

<add namespace="System.Text.RegularExpressions" />

<add namespace="System.Web" />

<add namespace="System.Web.Caching" />

<add namespace="System.Web.DynamicData" />

<add namespace="System.Web.SessionState" />

<add namespace="System.Web.Security" />

<add namespace="System.Web.Profile" />

<add namespace="System.Web.UI" />

<add namespace="System.Web.UI.WebControls" />

<add namespace="System.Web.UI.WebControls.WebParts" />

<add namespace="System.Web.UI.HtmlControls" />

<add namespace="System.Xml.Linq" />

</namespaces>From this XML list, you can see that quite a few namespaces are imported into every one of your ASP.NET pages. Again, you can feel free to modify this selection in the root web.config file or even make a similar selection of namespaces from within your application’s web.config file.

For instance, you can import your own namespace in the web.config file of your application to make the namespace available on every page where it is utilized.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<configuration>

<system.web>

<compilation debug="true" targetFramework="4.5" />

<httpRuntime targetFramework="4.5" />

<pages>

<namespaces>

<add namespace="Widgets" />

</namespaces>

</pages>

</system.web>

</configuration>Remember that importing a namespace into your ASP.NET page or user control gives you the opportunity to use the classes without fully identifying the class name. For example, by importing the namespace System.IO into the ASP.NET page, you can refer to classes within this namespace by using the singular class name (Directory instead of System.IO.Directory).

The @Implements directive gets the ASP.NET page to implement a specified .NET Framework interface. This directive supports only a single attribute: Interface.

The Interface attribute directly specifies the .NET Framework interface. When the ASP.NET page or user control implements an interface, it has direct access to all its events, methods, and properties.

Here is an example of the @Implements directive:

<%@ Implements Interface="System.Web.UI.IValidator" %>The @Register directive associates aliases with namespaces and class names for notation in custom server control syntax. You can see the use of the @Register directive when you drag and drop a user control onto any of your .aspx pages. Dragging a user control onto the .aspx page causes Visual Studio 2012 to create a @Register directive at the top of the page. This registers your user control on the page so that the control can then be accessed on the .aspx page by a specific name.

The @Register directive supports five attributes, as described in Table 3-7.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| Assembly | The assembly you are associating with the TagPrefix |

| Namespace | The namespace to relate with the TagPrefix |

| Src | The location of the user control |

| TagName | The alias to relate to the class name |

| TagPrefix | The alias to relate to the namespace |

Here is an example of how to use the @Register directive to import a user control to an ASP.NET page:

<%@ Register TagPrefix="MyTag" Namespace="MyNamespace"

Assembly="MyAssembly" %>The @Assembly directive attaches assemblies, the building blocks of .NET applications, to an ASP.NET page or user control as it compiles, thereby making all the assembly’s classes and interfaces available to the page. This directive supports two attributes, as shown in Table 3-8.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| Name | Enables you to specify the name of an assembly used to attach to the page files. The name of the assembly should include the filename only, not the file’s extension. For instance, if the file is MyAssembly.vb, the value of the name attribute should be MyAssembly. |

| Src | Enables you to specify the source of the assembly file to use in compilation. |

The following provides some examples of how to use the @Assembly directive:

<%@ Assembly Name="MyAssembly" %>

<%@ Assembly Src="MyAssembly.vb" %>This directive is used to specify the page from which any cross-page postings originate. Cross-page posting between ASP.NET pages is explained later in the section “Cross-Page Posting.”

The @PreviousPageType works with the cross-page posting capability that ASP.NET 4.5 provides. This directive contains two attributes as shown in Table 3-9.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| TypeName | Sets the name of the derived class from which the postback will occur |

| VirtualPath | Sets the location of the posting page from which the postback will occur |

The @MasterType directive associates a class name to an ASP.NET page to get at strongly typed references or members contained within the specified master page. This directive supports two attributes, as shown in Table 3-10.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| TypeName | Sets the name of the derived class from which to get strongly typed references or members |

| VirtualPath | Sets the location of the page from which these strongly typed references and members will be retrieved |

Details of how to use the @MasterType directive are shown in Chapter 16. Here is an example of its use:

<%@ MasterType VirtualPath="~/Wrox.master" %>The @OutputCache directive controls the output caching policies of an ASP.NET page or user control. This directive supports the attributes described in Table 3-11.

| ATTRIBUTE | DESCRIPTION |

| CacheProfile | Allows for a central way to manage an application’s cache profile. Use the CacheProfile attribute to specify the name of the cache profile detailed in the web.config file. |

| Duration | The duration of time in seconds that the ASP.NET page or user control is cached. |

| Location | Location enumeration value. The default is Any. This is valid for .aspx pages only and does not work with user controls (.ascx). Other possible values include Client, Downstream, None, Server, and ServerAndClient. |

| NoStore | Specifies whether to send a no-store header with the page. |

| Shared | Specifies whether a user control’s output can be shared across multiple pages. This attribute takes a Boolean value and the default setting is False. |

| SqlDependency | Enables a particular page to use SQL Server cache invalidation. |

| VaryByContentEncodings | Semicolon-separated list of strings used to vary the output cache based on content encodings. |

| VaryByControl | Semicolon-separated list of strings used to vary the output cache of a user control. |

| VaryByCustom | String specifying the custom output caching requirements. |

| VaryByHeader | Semicolon-separated list of HTTP headers used to vary the output cache. |

| VaryByParam | Semicolon-separated list of strings used to vary the output cache. |

Here is an example of how to use the @OutputCache directive:

<%@ OutputCache Duration="180" VaryByParam="None" %>Remember that the Duration attribute specifies the amount of time in seconds during which this page is to be stored in the system cache.

The @Reference directive declares that another ASP.NET page or user control should be compiled along with the active page or control. This directive contains a single attribute, the VirtualPath attribute. VirtualPath contains a location of the page or user control from which the active page will be referenced.

Here is an example of how to use the @Reference directive:

<%@ Reference VirtualPath="~/MyControl.ascx" %>ASP.NET developers consistently work with various events in their server-side code. Many of the events that they work with pertain to specific server controls. For instance, if you want to initiate some action when the end user clicks a button on your web page, you create a button-click event in your server-side code, as shown in Listing 3-4 (Listing03-04.aspx.cs in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-4: A sample button-click event shown in C#

protected void VerifyDataButton_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

// Verify Data

}In addition to the server controls, developers also want to initiate actions at specific moments when the ASP.NET page is being either created or destroyed. The ASP.NET page itself has always had a number of events for these instances. Since the inception of ASP.NET, the following page events are available:

One of the more popular page events from this list is the Load event, which is used in C# as shown in Listing 3-5 (Listing03-05.aspx.cs in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-5: Using the Page_Load event

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Response.Write("This is the Page_Load event");

}Besides the page events just shown, ASP.NET 4.5 has the following events:

An example of using any of these events, such as the PreInit event, is shown in Listing 3-6 (Listing03-06.aspx.vb and Listing03-06.aspx.cs in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-6: Using page events

VB

Private Sub Page_PreInit(sender As Object, e As EventArgs) Handles Me.PreInit

Page.Theme = Request.QueryString("ThemeChange")

End SubC#

protected void Page_PreInit(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Page.Theme = Request.QueryString["ThemeChange"];

}If you create an ASP.NET 4.5 page and turn on tracing, you can see the order in which the main page events are initiated. They are fired in the order shown in Figure 3-7.

With the addition of these choices, you can now work with the page and the controls on the page at many points in the page-compilation process. You see these useful page events in code examples throughout the book.

When you are working with ASP.NET pages, be sure you understand the page events just listed. They are important because you place a lot of your page behavior inside these events at specific points in a page lifecycle.

In Active Server Pages 3.0, developers had their pages post to other pages within the application. ASP.NET pages typically post back to themselves to process events (such as a button-click event).

For this reason, you must differentiate between posts for the first time a page is loaded by the end user and postbacks. A postback is just that — a posting back to the same page. The postback contains all the form information collected on the initial page for processing if required.

Because of all the postbacks that can occur with an ASP.NET page, you want to know whether a request is the first instance for a particular page or is a postback from the same page. You can make this check by using the IsPostBack property of the Page class, as shown in the following example:

VB

If Not Page.IsPostBack Then

' Do processing

End IfC#

if (!Page.IsPostBack) {

// Do processing

}One common feature in ASP 3.0 that was difficult to achieve in early versions of ASP.NET is the capability to do cross-page posting. Cross-page posting enables you to submit a form (say, Page1.aspx) and have this form and all the control values post themselves to another page (Page2.aspx).

Traditionally, any page created in ASP.NET 1.0/1.1 simply posted to itself, and you handled the control values within this page instance. You could differentiate between the page’s first request and any postbacks by using the Page.IsPostBack property, as shown earlier in this chapter.

Even with this capability, many developers still wanted to be able to post to another page and deal with the first page’s control values on that page. This is something that is possible in ASP.NET 4.5, and it is quite a simple process.

For an example, create a page called Page1.aspx that contains a simple form. Listing 3-7 shows this page; you can find the code for this listing in Listing03-07 (Page 1).aspx in the code download for the chapter.

LISTING 3-7: Page1.aspx

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<script runat="server">

Protected Sub Button1_Click(sender As Object,

e As System.EventArgs)

Label1.Text = "Hello " & TextBox1.Text & "<br />" &

"Date Selected: " & Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString()

End Sub

</script>

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head runat="server">

<title>First Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">

Enter your name:<br />

<asp:Textbox ID="TextBox1" Runat="server"></asp:Textbox>

<p>

When do you want to fly?<br />

<asp:Calendar ID="Calendar1" Runat="server"></asp:Calendar>

</p>

<br />

<asp:Button ID="Button1" Runat="server" Text="Submit page to itself"

OnClick="Button1_Click" />

<asp:Button ID="Button2" Runat="server" Text="Submit page to Page2.aspx"

PostBackUrl="Page2.aspx" />

<p>

<asp:Label ID="Label1" Runat="server"></asp:Label>

</p>

</form>

</body>

</html>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<script runat="server">

protected void Button1_Click(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Label1.Text = "Hello " + TextBox1.Text + "<br />" +

"Date Selected: " + Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString();

}

</script>The code from Page1.aspx, as shown in Listing 3-7, is quite interesting. Two buttons are shown on the page. Both buttons submit the form, but each submits the form to a different location. The first button submits the form to itself. This is the behavior that has been the default for ASP.NET 1.0/1.1. In fact, nothing is different about Button1. It submits to Page1.aspx as a postback because of the use of the OnClick property in the button control. A Button1_Click method on Page1.aspx handles the values that are contained within the server controls on the page.

The second button, Button2, works quite differently. This button does not contain an OnClick method as the first button did. Instead, it uses the PostBackUrl property. This property takes a string value that points to the location of the file to which this page should post. In this case, it is Page2.aspx. This means that Page2.aspx now receives the postback and all the values contained in the Page1.aspx controls. Look at the code for Page2.aspx, shown in Listing 3-8 (Listing03-08 (Page 2).aspx in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-8: Page2.aspx

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<script runat="server">

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As System.EventArgs)

Dim pp_Textbox1 As TextBox

Dim pp_Calendar1 As Calendar

pp_Textbox1 = CType(PreviousPage.FindControl("Textbox1"), TextBox)

pp_Calendar1 = CType(PreviousPage.FindControl("Calendar1"), Calendar)

Label1.Text = "Hello " & pp_Textbox1.Text & "<br />" &

"Date Selected: " & pp_Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString()

End Sub

</script>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<head runat="server">

<title>Second Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">

<asp:Label ID="Label1" Runat="server"></asp:Label>

</form>

</body>

</html>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<script runat="server">

protected void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

TextBox pp_TextBox1;

Calendar pp_Calendar1;

pp_TextBox1 = (TextBox)PreviousPage.FindControl("TextBox1");

pp_Calendar1 = (Calendar)PreviousPage.FindControl("Calendar1");

Label1.Text = "Hello " + pp_TextBox1.Text + "<br />" +

"Date Selected: " + pp_Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString();

}

</script>You have a couple of ways of getting at the values of the controls that are exposed from Page1.aspx from the second page. The first option is displayed in Listing 3-8. To get at a particular control’s value that is carried over from the previous page, you simply create an instance of that control type and populate this instance using the FindControl() method from the PreviousPage property. The String value assigned to the FindControl() method is the Id value, which is used for the server control from the previous page. After this is assigned, you can work with the server control and its carried-over values just as if it had originally resided on the current page. You can see from the example that you can extract the Text and SelectedDate properties from the controls without any problem.

Another way of exposing the control values from the first page (Page1.aspx) is to create a Property for the control, as shown in Listing 3-9 (code file Listing03-09 (Page 1).aspx in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-9: Exposing the values of the control from a property

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<script runat="server">

Public ReadOnly Property pp_TextBox1() As TextBox

Get

Return TextBox1

End Get

End Property

Public ReadOnly Property pp_Calendar1() As Calendar

Get

Return Calendar1

End Get

End Property

</script>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<script runat="server">

public TextBox pp_TextBox1 { get { return TextBox1; } }

public Calendar pp_Calendar1 { get { return Calendar1; } }

</script>Now that these properties are exposed on the posting page, the second page (Page2.aspx) can more easily work with the server control properties that are exposed from the first page. Listing 3-10 shows you how Page2.aspx works with these exposed properties (Listing03-10 (Page 2).aspx in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-10: Consuming the exposed properties from the first page

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<%@ PreviousPageType VirtualPath="Page1.aspx" %>

<script runat="server">

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As System.EventArgs)

Label1.Text = "Hello " & PreviousPage.pp_Textbox1.Text & "<br />" &

"Date Selected: " &

PreviousPage.pp_Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString()

End Sub

</script>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<%@ PreviousPageType VirtualPath="Page1.aspx" %>

<script runat="server">

protected void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Label1.Text = "Hello " + PreviousPage.pp_TextBox1.Text + "<br />" +

"Date Selected: " +

PreviousPage.pp_Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString();

}

</script>To be able to work with the properties that Page1.aspx exposes, you have to strongly type the PreviousPage property to Page1.aspx. To do this, you use the PreviousPageType directive. This directive allows you to specifically point to Page1.aspx with the use of the VirtualPath attribute.

Notice that when you are cross posting from one page to another, you are not restricted to working only with the postback on the second page. In fact, you can still create methods on Page1.aspx that work with the postback before moving onto Page2.aspx. To do this, you simply add an OnClick event for the button in Page1.aspx and a method. You also assign a value for the PostBackUrl property. You can then work with the postback on Page1.aspx and then again on Page2.aspx.

What happens if users request Page2.aspx before they work their way through Page1.aspx? Determining whether the request is coming from Page1.aspx or whether someone just hit Page2.aspx directly is actually quite easy. You can work with the request through the use of the IsCrossPagePostBack property that is quite similar to the IsPostBack property. The IsCrossPagePostBack property enables you to check whether the request is from Page1.aspx. Listing 3-11 (Listing03-11.aspx in the code download for this chapter) shows an example of this.

LISTING 3-11: Using the IsCrossPagePostBack property

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<%@ PreviousPageType VirtualPath="Page1.aspx" %>

<script runat="server">

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As System.EventArgs)

If PreviousPage IsNot Nothing AndAlso PreviousPage.IsCrossPagePostBack Then

Label1.Text = "Hello " & PreviousPage.pp_Textbox1.Text & "<br />" &

"Date Selected: " &

PreviousPage.pp_Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString()

Else

Response.Redirect("Page1.aspx")

End If

End Sub

</script>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<%@ PreviousPageType VirtualPath="Page1.aspx" %>

<script runat="server">

protected void Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs e)

{

if (PreviousPage != null && PreviousPage.IsCrossPagePostBack)

{

Label1.Text = "Hello " + PreviousPage.pp_TextBox1.Text + "<br />" +

"Date Selected: " +

PreviousPage.pp_Calendar1.SelectedDate.ToShortDateString();

}

else

{

Response.Redirect("Page1.aspx");

}

}

</script>When you create ASP.NET applications, notice that ASP.NET 4.5 uses a file-based approach. When working with ASP.NET, you can add as many files and folders as you want within your application without recompiling every time a new file is added to the overall solution. ASP.NET 4.5 includes the capability to automatically precompile your ASP.NET applications dynamically.

ASP.NET 1.0/1.1 compiled everything in your solution into a DLL. This is no longer necessary because ASP.NET applications now have a defined folder structure. By using the ASP.NET-defined folders, you can have your code automatically compiled for you, your application themes accessible throughout your application, and your globalization resources available whenever you need them. To gain a better understanding, let’s review each of the defined folders to see how they work. The first folder reviewed is the App_Code folder.

The App_Code folder is meant to store your classes, .wsdl files, and typed data sets. Any of these items stored in this folder are then automatically available to all the pages within your solution. The nice thing about the App_Code folder is that when you place something inside it, Visual Studio 2012 automatically detects this and compiles it if it is a class (.vb or .cs), automatically creates your XML web service proxy class (from the .wsdl file), or automatically creates a typed data set for you from your .xsd files. After the files are automatically compiled, these items are then instantaneously available to any of your ASP.NET pages that are in the same solution. Look at how to employ a simple class in your solution using the App_Code folder.

The first step is to create an App_Code folder. To do this, simply right-click the solution and choose Add ⇒ Add ASP.NET Folder ⇒ App_Code. After the App_Code folder is in place, right-click the folder and select Add New Item. The Add New Item dialog box (as shown in Figure 3-8) that appears gives you a few options for the types of files that you can place within this folder. The available options include an Ajax-enabled WCF Service, a Class file, a LINQ to SQL Class, an ADO.NET Entity Data Model, an ADO.NET EntityObject Generator, a Sequence Diagram, a Text Template, a Text file, a DataSet, a Report, and a Class Diagram if you are using Visual Studio 2012. Visual Studio 2012 Express for Web offers only a subset of these files. For the first example, select the file of type Class and name the class Calculator.vb or Calculator.cs. Listing 3-12 shows this class, and it can be found in this chapter’s code download as Calculator.vb and Calculator.cs.

LISTING 3-12: The Calculator class

VB

Public Class Calculator

Public Function Add(a As Integer, b As Integer) As Integer

Return (a + b)

End Function

End ClassC#

public class Calculator

{

public int Add(int a, int b)

{

return (a + b);

}

}What’s next? Just save this file, and it is now available to use in any pages that are in your solution. To see this in action, create a simple .aspx page that has just a single Label server control. Listing 3-13 (Calculator.aspx in the code download) shows you the code to place within the Page_Load event to make this new class available to the page.

LISTING 3-13: An .aspx page that uses the Calculator class

VB

<%@ Page Language="vb" %>

<script runat="server">

Protected Sub Page_Load(ByVal sender As Object, ByVal e As System.EventArgs)

Dim myCalc As New Calculator

Label1.Text = myCalc.Add(12, 12)

End Sub

</script>C#

<%@ Page Language="C#" %>

<script runat="server">

protected void Page_Load(Object s, EventArgs e)

{

Calculator myCalc = new Calculator();

Label1.Text = myCalc.Add(12, 12).ToString();

}

</script>When you run this .aspx page, notice that it utilizes the Calculator class without any problem, with no need to compile the class before use. In fact, right after saving the Calculator class in your solution or moving the class to the App_Code folder, you also instantaneously receive IntelliSense capability on the methods that the class exposes (as illustrated in Figure 3-9).

To see how Visual Studio 2012 works with the App_Code folder, open the Calculator class again in the IDE and add a Subtract method. Your class should now appear as shown in Listing 3-14, which can be found in this chapter’s code download as Calculator.vb and Calculator.cs.

LISTING 3-14: Adding a Subtract method to the Calculator class

VB

Public Class Calculator

Public Function Add(a As Integer, b As Integer) As Integer

Return (a + b)

End Function

Public Function Subtract(a As Integer, b As Integer) As Integer

Return (a - b)

End Function

End ClassC#

public class Calculator

{

public int Add(int a, int b)

{

return (a + b);

}

public int Subtract(int a, int b)

{

return (a - b);

}

}After you have added the Subtract method to the Calculator class, save the file and go back to your .aspx page. Notice that the class has been recompiled by the IDE, and the new method is now available to your page. You see this directly in IntelliSense. Figure 3-10 shows this in action.

Everything placed in the App_Code folder is compiled into a single assembly. The class files placed within the App_Code folder are not required to use a specific language. This means that even if all the pages of the solution are written in Visual Basic, the Calculator class in the App_Code folder of the solution can be built in C# (Calculator.cs).

Because all the classes contained in this folder are built into a single assembly, you cannot have classes of different languages sitting in the root App_Code folder, as in the following example:

\App_Code

Calculator.cs

AdvancedMath.vbHaving two classes made up of different languages in the App_Code folder (as shown here) causes an error to be thrown. It is impossible for the assigned compiler to work with two different languages. Therefore, to be able to work with multiple languages in your App_Code folder, you must make some changes to the folder structure and to the web.config file.

The first step is to add two new subfolders to the App_Code folder — a VB folder and a CS folder. This gives you the following folder structure:

\App_Code

\VB

Add.vb

\CS

Subtract.csThis still will not correctly compile these class files into separate assemblies, at least not until you make some additions to the web.config file. Most likely, you do not have a web.config file in your solution at this moment, so add one through the Solution Explorer. After it is added, change the <compilation> node so that it is structured as shown in Listing 3-15 (web.config in the code download for this chapter).

LISTING 3-15: Structuring the web.config file so that classes in the App_Code folder can use different languages

<compilation debug="false" targetFramework="4.5">

<codeSubDirectories>

<add directoryName="VB"></add>

<add directoryName="CS"></add>

</codeSubDirectories>

</compilation>Now that this is in place in your web.config file, you can work with each of the classes in your ASP.NET pages. In addition, any C# class placed in the CS folder is now automatically compiled just like any of the classes placed in the VB folder. Because you can add these directories in the web.config file, you are not required to name them VB and CS as they are here; you can use whatever name you like.

The App_Data folder holds the data stores utilized by the application. It is a good spot to centrally store all the data stores your application might use. The App_Data folder can contain Microsoft SQL Express files (.mdf files), Microsoft SQL Server Compact files (.sdf files), XML files, and more.

The user account utilized by your application will have read and write access to any of the files contained within the App_Data folder. Another reason for storing all your data files in this folder is that much of the ASP.NET system — from the membership and role-management systems to the GUI tools, such as the ASP.NET MMC snap-in and ASP.NET Web Site Administration Tool — is built to work with the App_Data folder.

Resource files are string tables that can serve as data dictionaries for your applications when these applications require changes to content based on things such as changes in culture. You can add Assembly Resource Files (.resx) to the App_GlobalResources folder, and they are dynamically compiled and made part of the solution for use by all your .aspx pages in the application. When using ASP.NET 1.0/1.1, you had to use the resgen.exe tool and had to compile your resource files to a .dll or .exe for use within your solution. Dealing with resource files in ASP.NET 4.5 is considerably easier. Simply placing your application-wide resources in this folder makes them instantly accessible. Localization is covered in detail in Chapter 32.

Even if you are not interested in constructing application-wide resources using the App_GlobalResources folder, you may want resources that can be used for a single .aspx page. You can do this very simply by using the App_LocalResources folder.

You can add resource files that are page-specific to the App_LocalResources folder by constructing the name of the .resx file in the following manner:

Now, the resource declarations used on the Default.aspx page are retrieved from the appropriate file in the App_LocalResources folder. By default, the Default.aspx.resx resource file is used if another match is not found. If the client is using a culture specification of fi-FI (Finnish), however, the Default.aspx.fi.resx file is used instead. Localization of local resources is covered in detail in Chapter 32.

The App_WebReferences folder is a new name for the previous Web References folder that was used in versions of ASP.NET prior to ASP.NET 3.5. Now you can use the App_WebReferences folder and have automatic access to the remote web services referenced from your application. Chapter 13 covers web services in ASP.NET.

The App_Browsers folder holds .browser files, which are XML files used to identity the browsers making requests to the application and understanding the capabilities these browsers have. You can find a list of globally accessible .browser files at C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.xxxxx\Config\Browsers. In addition, if you want to change any part of these default browser definition files, just copy the appropriate .browser file from the Browsers folder to your application’s App_Browsers folder and change the definition.

You already saw how Visual Studio 2012 compiles pieces of your application as you work with them (for instance, by placing a class in the App_Code folder). The other parts of the application, such as the .aspx pages, can be compiled just as they were in earlier versions of ASP.NET by referencing the pages in the browser.

When an ASP.NET page is referenced in the browser for the first time, the request is passed to the ASP.NET parser that creates the class file in the language of the page. It is passed to the ASP.NET parser based on the file’s extension (.aspx) because ASP.NET realizes that this file extension type is meant for its handling and processing. After the class file has been created, the class file is compiled into a DLL and then written to the disk of the web server. At this point, the DLL is instantiated and processed, and an output is generated for the initial requester of the ASP.NET page. This is detailed in Figure 3-11.

On the next request, great things happen. Instead of going through the entire process again for the second and respective requests, the request simply causes an instantiation of the already-created DLL, which sends out a response to the requester. This is illustrated in Figure 3-12.

Because of the mechanics of this process, if you made changes to your .aspx code-behind pages, you found it necessary to recompile your application. This was quite a pain if you had a larger site and did not want your end users to experience the extreme lag that occurs when an .aspx page is referenced for the first time after compilation. Many developers, consequently, began to develop their own tools that automatically go out and hit every single page within their application to remove this first-time lag hit from the end user’s browsing experience.

ASP.NET provides a few ways to precompile your entire application with a single command that you can issue through a command line. One type of compilation is referred to as in-place precompilation. To precompile your entire ASP.NET application, you must use the aspnet_compiler.exe tool that comes with ASP.NET. You navigate to the tool using the Command window. Open the Command window and navigate to C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.xxxxx\. When you are there, you can work with the aspnet_compiler tool. You can also get to this tool directly from the Developer Command Prompt for VS2012. In Windows 8, choose the Search charm and enter Developer Command Prompt. Choose the appropriate application from the search results.

After you get the command prompt, you use the aspnet_compiler.exe tool to perform an in-place precompilation using the following command:

aspnet_compiler -p "C:\Inetpub\wwwroot\WROX" -v noneYou then get a message stating that the precompilation is successful. The other great thing about this precompilation capability is that you can also use it to find errors on any of the ASP.NET pages in your application. Because it hits every page, if one of the pages contains an error that won’t be triggered until run time, you get notification of the error immediately as you employ this precompilation method.

The next precompilation option is commonly referred to as precompilation for deployment. This outstanding capability of ASP.NET enables you to compile your application down to some DLLs, which can then be deployed to customers, partners, or elsewhere for your own use. Not only are minimal steps required to do this, but also after your application is compiled, you simply have to move around the DLL and some placeholder files for the site to work. This means that your website code is completely removed and placed in the DLL when deployed.

However, before you take these precompilation steps, create a folder in your root drive called, for example, Wrox. This folder is the one to which you will direct the compiler output. When it is in place, you can return to the compiler tool and give the following command:

aspnet_compiler -v [Application Name] -p [Physical Location] [Target]Therefore, if you have an application called ThomsonReuters located at C:\Websites\ThomsonReuters, you use the following commands:

aspnet_compiler -v /ThomsonReuters -p C:\Websites\ThomsonReuters C:\WroxPress the Enter key, and the compiler either tells you that it has a problem with one of the command parameters or that it was successful (shown in Figure 3-13). If it was successful, you can see the output placed in the target directory.

In Figure 3-13, -v is a command for the virtual path of the application, which is provided by using /ThomsonReuters. The next command is –p, which is pointing to the physical path of the application. In this case, it is C:\Websites\ThomsonReuters. Finally, the last bit, C:\Wrox, is the location of the compiler output. Table 3-12 describes some of the possible commands for the aspnet_compiler.exe tool.

| COMMAND | DESCRIPTION |

| -m | Specifies the full IIS metabase path of the application. If you use the -m command, you cannot use the -v or -p command. |

| -v | Specifies the virtual path of the application to be compiled. If you also use the -p command, the physical path is used to find the location of the application. |

| -p | Specifies the physical path of the application to be compiled. If this is not specified, the IIS metabase is used to find the application. |

| -u | If this command is utilized, it specifies that the application is updatable. |

| -f | Specifies to overwrite the target directory if it already exists. |

| -d | Specifies that the debug information should be excluded from the compilation process. |

| -c | Specifies that the application to be compiled should be completely rebuilt. |

| [targetDir] | Specifies the target directory where the compiled files should be placed. If this is not specified, the output files are placed in the application directory. |

After compiling the application, you can go to C:\Wrox to see the output. Here you see all the files and the file structures that were in the original application. However, if you look at the content of one of the files, notice that the file is simply a placeholder. In the actual file, you find the following comment:

This is a marker file generated by the precompilation tool

and should not be deleted!In fact, you find one or more App_Web_XXXXXXXX.dll files in the bin folder where all the page code is located. Because it is in a DLL file, it provides great code obfuscation as well. From here on, all you do is move these files to another server using FTP or Windows Explorer, and you can run the entire web application from these files. When you have an update to the application, you simply provide a new set of compiled files. Figure 3-14 shows a sample output.

Note that this compilation process does not compile every type of web file. In fact, it compiles only the ASP.NET-specific file types and leaves out of the compilation process the following types of files:

You cannot do much to get around this, except in the case of the HTML files and the text files. For these file types, just change the file extensions of these file types to .aspx; they are then compiled into the App_Web_XXXXXXXX.dll like all the other ASP.NET files.

As you review the various ASP.NET folders, note that one of the more interesting folders is the App_Code folder. You can simply drop code files, XSD files, and even WSDL files directly into the folder for automatic compilation. When you drop a class file into the App_Code folder, the class can automatically be utilized by a running application. In the early days of ASP.NET, if you wanted to deploy a custom component, you had to precompile the component before being able to utilize it within your application. Now ASP.NET simply takes care of all the work that you once had to do. You do not need to perform any compilation routine.

Which file types are compiled in the App_Code folder? As with most things in ASP.NET, this is determined through settings applied in a configuration file. Listing 3-16 shows a snippet of configuration code taken from the master web.config file found in ASP.NET 4.5. Please note that this listing is not included in the source code available for download because the web.config listed here is installed with the .NET 4.5 Framework.

LISTING 3-16: Reviewing the list of build providers

<buildProviders>

<add extension=".aspx" type="System.Web.Compilation.PageBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".ascx"

type="System.Web.Compilation.UserControlBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".master"

type="System.Web.Compilation.MasterPageBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".asmx" type="System.Web.Compilation.WebServiceBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".ashx" type="System.Web.Compilation.WebHandlerBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".soap" type="System.Web.Compilation.WebServiceBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".resx" type="System.Web.Compilation.ResXBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".resources"

type="System.Web.Compilation.ResourcesBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".wsdl" type="System.Web.Compilation.WsdlBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".xsd" type="System.Web.Compilation.XsdBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".js" type="System.Web.Compilation.ForceCopyBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".lic" type="System.Web.Compilation.IgnoreFileBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".licx" type="System.Web.Compilation.IgnoreFileBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".exclude"

type="System.Web.Compilation.IgnoreFileBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".refresh"

type="System.Web.Compilation.IgnoreFileBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".edmx"

type="System.Data.Entity.Design.AspNet.EntityDesignerBuildProvider" />

<add extension=".xoml"

type="System.ServiceModel.Activation.WorkflowServiceBuildProvider,

System.WorkflowServices, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add extension=".svc"

type="System.ServiceModel.Activation.ServiceBuildProvider,

System.ServiceModel.Activation, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />

<add extension=".xamlx" type="System.Xaml.Hosting.XamlBuildProvider,

System.Xaml.Hosting, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral,

PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35" />