The Canadian Morley Callaghan, at one time well known in the United States, is today perhaps the most unjustly neglected novelist in the English-speaking world. In his youth, he worked on the Toronto Star – Toronto is his native city – at the time when Ernest Hemingway had a job on the same paper, and, through Hemingway, who took his manuscripts to Paris, some of Callaghan’s early short stories were accepted by Ezra Pound for his little magazine Exile. Maxwell Perkins of Scribner’s was impressed by these stories and had them reprinted in Scribner’s Magazine, which later published other stories by Callaghan. His novels were published by Scribner’s. Morley Callaghan was a friend of Fitzgerald and Hemingway and was praised by Ring Lardner, and he belonged to the literary scene of the twenties. He appeared in transition as well as in Scribner’s and he spent a good deal of his time in Paris and the United States. But eventually he went back to Canada, and it is one of the most striking signs of signs of the partial isolation of that country from the rest of the cultural world that – in spite of the fact that his stories continued to appear in The New Yorker up to the end of the thirties – he should quickly have been forgotten in the United States and should be almost unknown in England. Several summers ago, on a visit to Toronto, I was given a copy of the Canadian edition of a novel of his called The Loved and the Lost. It seemed to me so remarkable that I expected it to attract attention in England and the United States. But it was never published in England, and it received so little notice in the United States that I imagined it had not been published here either.

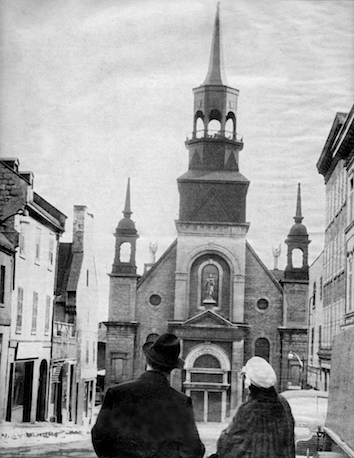

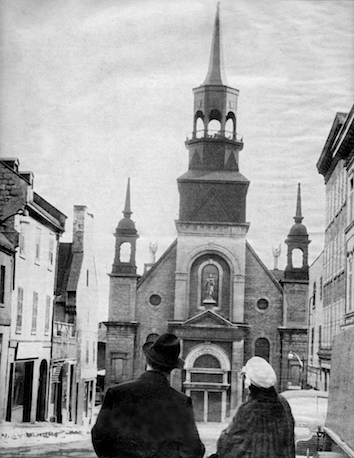

I want to… speculate first on the reasons for the current indifference to his work. This has no doubt been partly due to the peculiar relation of Canada to England and the United States. The Canadian background of Morley Callaghan’s stories seems alien to both these other countries and at the same time not strange enough to exercise the spell of the truly exotic. To the reviewer, this background has much interest and charm. Montreal, with its snow-dazzling mountain, its passionate winter sports, its hearty and busy bars, its jealously guarded French culture, and its pealing of bells from French churches, side by side with the solid Presbyterianism of its Anglo-Scottish best people, is a world I find pleasant to explore. It is curious to see how much this world has been influenced – in its language, in its amusements, its press – by the “Americans,” as they still call us, and how far – in, for example, its parliamentary politics and its social and moral codes – it rests on somewhat different foundations. But Mr. Callaghan is not writing about Canada at all from the point of view of exploiting its regional characteristics… he does not even tell the reader that the scene of the story is Montreal. The landscapes, the streets and the houses, the atmosphere of the various milieu are known intimately and sensitively observed, but they are made to figure quite unobtrusively; there are no very long descriptions and nothing like “documentation.” We simply find ourselves living with the characters and taking for granted, as they do, their habits and customs and assumptions, their near-Artic climate and their split nationality. Still less is Mr. Callaghan occupied with specifically Canadian problems. The new and militant Canadian nationalism – in these novels, at least – does not touch him; he is not here concerned with the question of “what it means to be a Canadian.” And the result of this has been, I believe, that a public, both here and in England, whose taste in American fiction seems to have been largely whetted by the perpetrators of violent scenes – and these include some of our best writers as well as our worst – does not find itself at home with, does not really comprehend, the more sober effects of Callaghan. In his novels one finds acts of violence and a certain amount of sensuality, but these are not used for melodrama or even for “symbolic” fables of the kind that is at present fashionable. There are no love stories that follow an expected course, not even any among those I have read that eventually come out all right. It is impossible to imagine these books transposed into any kind of terms that would make them acceptable to Hollywood.

The novels of Morley Callaghan do not deal, then, with his native Canada in any editorial or informative way, nor are they aimed at any popular taste, Canadian, American or British. They center on situations of primarily psychological interest that are treated from a moral point of view yet without making moral judgments of any conventional kind, and it is in consequence peculiarly difficult to convey the implications of one of these books by attempting to retell its story. The revelation of personality, of tacit conflict, of reciprocal emotion is conducted in so subtle a way that we are never quite certain what the characters are up to – they are often not certain themselves – or what the upshot of their relationships will be… These stories are extremely well told. The details, neither stereotyped nor clever – the casual gestures of the characters, the little incidents that have no direct bearing on their purposes or their actions, the people they see in restaurants or pass on the street – have a naturalness that gives the illusion of not having been invented, of that seeming irrelevance of life that is still somehow inextricably relevant. The narrative moves quietly but rapidly, and Mr. Callaghan is a master of suspense… The style is very clear and spare, sometimes a bit commonplace, but always intent on its purpose, always making exactly its points so that these novels are as different as possible from the contemporary bagful of words that forms the substance of so many current American books that are nevertheless taken seriously. Mr. Callaghan’s underplaying of drama and the unemphatic tone of his style are accompanied by a certain greyness of atmosphere, but this might also be said of Chekhov, whose short stories his sometimes resemble… one’s tendency, in writing of these novels, to speak of what the characters “should have” done is a proof of the extraordinary effect of reality which – by simply presenting their behaviour – Mr. Callaghan succeeds in producing. His people, though the dramas they enact have more than individual significance, are never allowed to appear as anything other than individuals. They never become types or abstractions, nor do they ever loom larger than life. They are never removed from our common humanity, and there is never any simple opposition of beautiful and horrible, of lofty and base. The tragedies are the results of the interactions of the weaknesses and strengths of several characters, none of whom is either entirely responsible or entirely without responsibility for the outcome that concerns them all. But in order to describe his book properly, one must explain that the central element in it, the spirit that pervades the whole, is deeply if undogmatically Christian. Though it depends on no scaffolding of theology, though it embodies an original vision, there is evidently somewhere behind it the tradition of the Catholic Church. This is not the acquired doctrine of the self-conscious Catholic convert – of Graham Greene or Evelyn Waugh. One is scarcely aware of doctrine; what one finds is, rather, an intuitive sense of the meaning of Christianity… The reviewer, at the end of this article, is now wondering whether the primary reason for the current underestimation of Morley Callaghan may not be simply a general incapacity – apparently shared by his compatriots – for believing that a writer whose work may be mentioned without absurdity in association with Chekhov’s and Turgenev’s can possibly be functioning in Toronto.

November 26, 1960