The Titanic letter that appears in Haunting the Deep has a fascinating story of its own, involving a long line of remarkable women from my family tree. It starts way back with my great-great-great-grandmother Maria (pronounced muh-RYE-uh) DeLong Haxtun, to whom the letter was written.

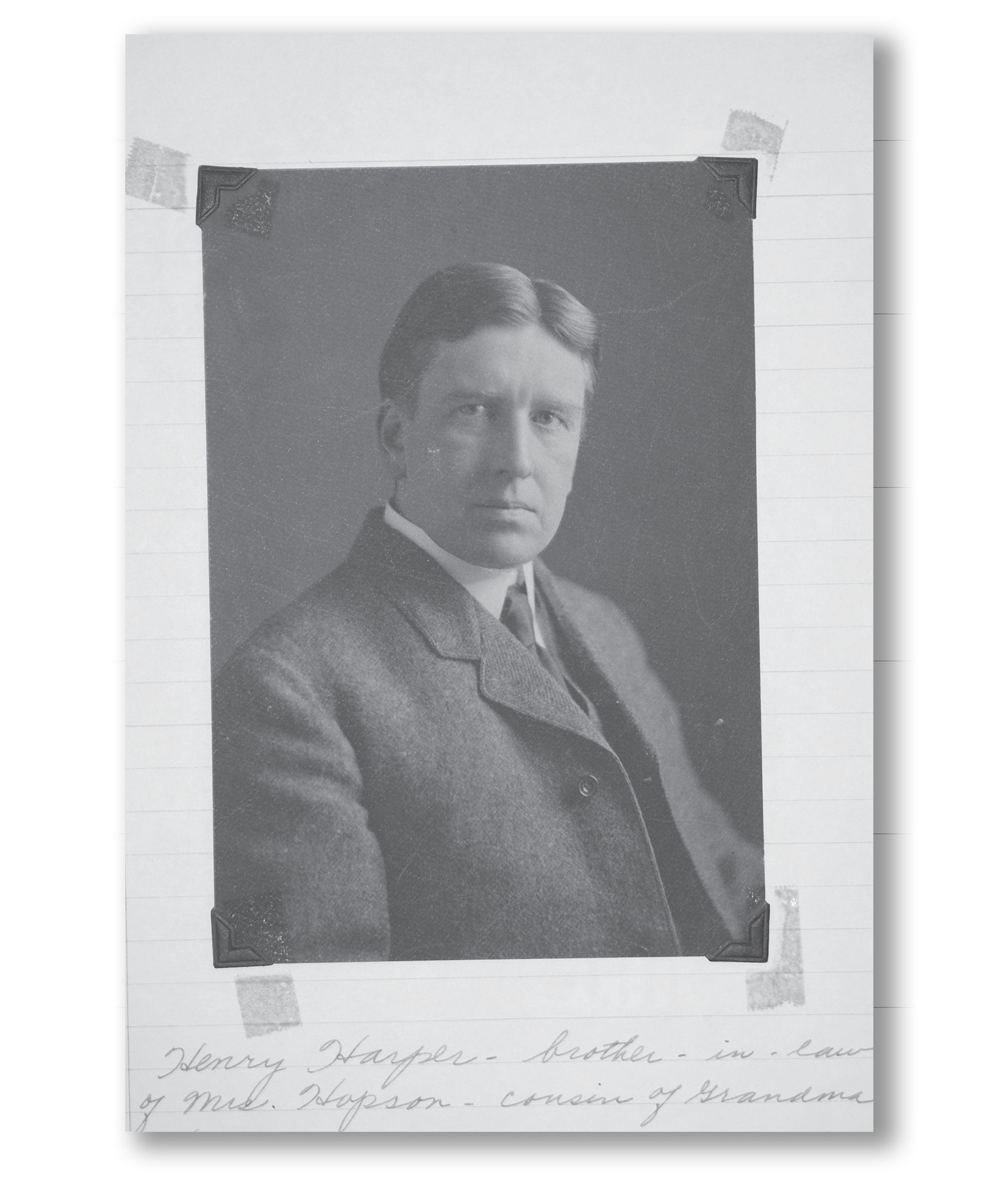

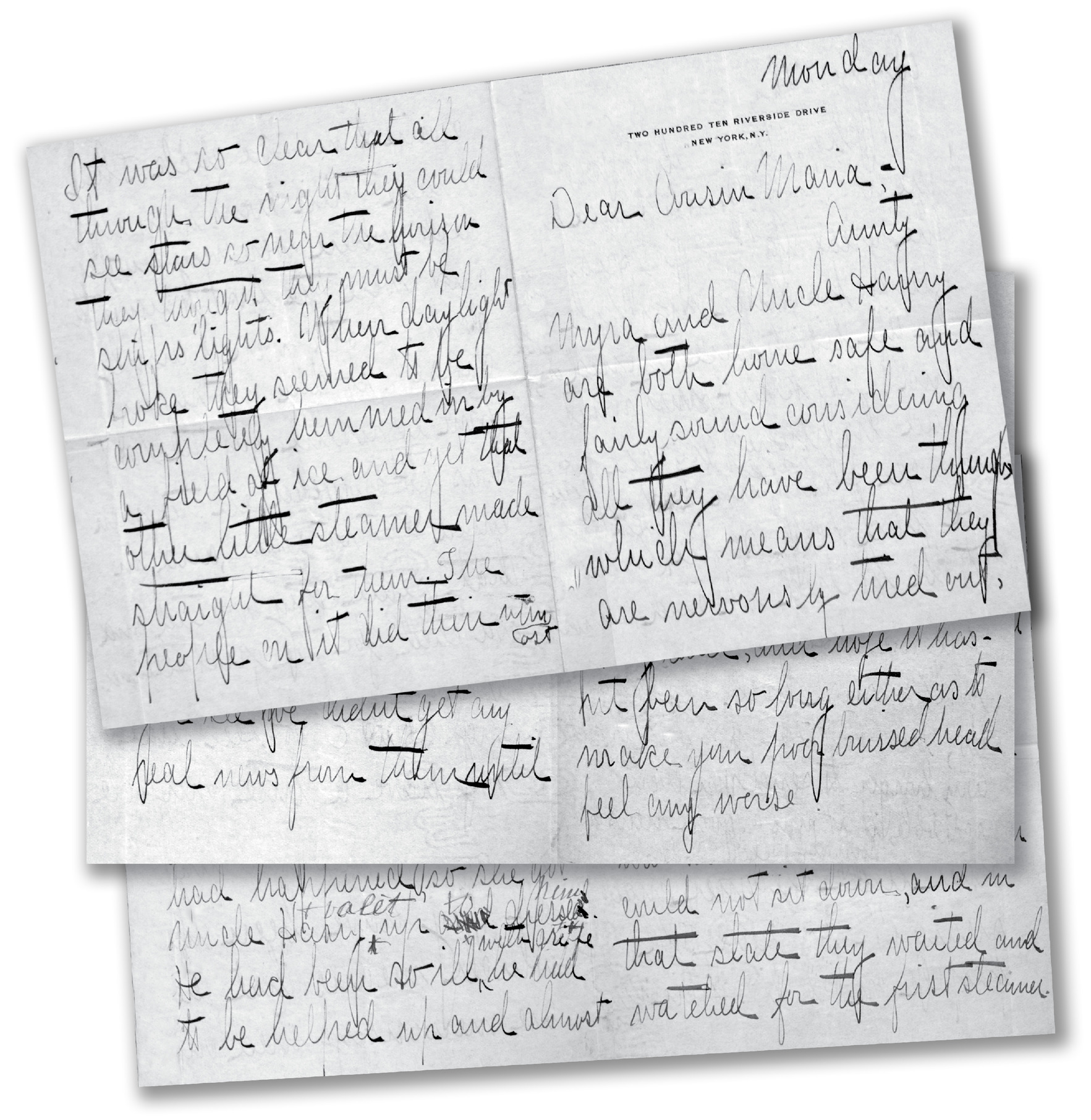

I’ve been able to track so many of my ancestors’ adventures through Maria’s robust and frequent correspondence—as far as I understand, she was quite the favorite in my family. (And I’ve got to say, reading all that gorgeous cursive makes me a little weepy that no one writes longhand anymore.) Maria received the letter recounting the fate of Myra Haxtun Harper and Henry Sleeper Harper—her cousins—shortly after the Titanic sank and the Harpers returned home safely. In addition to the Titanic letter, Maria also had a picture of Henry Harper in her possession.

Maria’s granddaughter—my great-grandmother—Adrianna Storm Haxtun Mather (I am proud to be named after her!) preserved Henry’s picture, the Titanic letter, and many newspaper clippings from 1912 related to the sinking. Adrianna was a teacher and an amateur historian, and labeled all the family heirlooms she collected over the years with notecards (hence the mention of notecards in this book and in How to Hang a Witch). The handwriting on the envelope containing the Titanic letter is hers, and so are the notes below Henry Harper’s picture.

This personal slice of Titanic history might have lingered in a box somewhere collecting dust, except that my grandmother Claire Mather had the foresight to pass on all the family stories. When I was a little girl, she held my hand and talked me through the many heirlooms that had fallen into her care, breathing life into old portraits and Victorian wedding dresses stashed in trunks. Romance, intrigue, and grandiose apology presents were all well represented.

The funny thing is, there is so much history in my grandparents’ home that you are just as likely to find a curious diary from the 1700s in the back of a button drawer as anywhere else. In fact, the Titanic letter was nestled among a stack of other old letters and newspapers in a desk. There was nothing to indicate that it was special besides the word “Titanic” written on a manila envelope. When I first stumbled across it, I thought, “No, not that Titanic. Couldn’t be.”

Also odd (or maybe kismet!) was that I discovered the letter right after Random House acquired How to Hang a Witch. Here I was with my first book deal and a letter about Henry Sleeper Harper’s brush with the Titanic—the same Henry who was the director of Harper & Brothers publishing house before it became HarperCollins. It seemed obvious to me that the next book I wrote should be about this letter and the incredible women who preserved it and handed it down through the generations.

Myra and Henry didn’t do interviews after the Titanic sank, and as far as I know, this is one of the only written records of what happened to them that night in 1912. They were unbelievably lucky in that they both survived, along with Hammad Hassab, who was in their employ, and their dog. Their survival was likely only possible because Myra saw the iceberg scrape past her porthole and realized the danger. She quickly woke her husband, and their entire party was able to board one of the first lifeboats.

As it turns out, in the moments after the ship struck the iceberg, many passengers were nervous about getting into the lifeboats. They were being told to trade an enormous, luxurious steamer that they believed was unsinkable for a tiny boat that would be lowered by rickety ropes fifty feet into icy black water. Even when the threat of sinking became more obvious, there were a number of people who needed to be coaxed or pushed into those lifeboats. Perhaps because of this reluctance early on in the boarding process, the crew allowed a few men to accompany their wives. Henry was ill at the time, and it’s possible that his weakened state, combined with the aforementioned hesitancy, played a role in his and Hammad’s survival.

The more I thought about Myra and Henry’s personal story and how they narrowly survived, the more I thought about people’s survival in general. The passengers and crew on the Titanic came from all over the world and were from vastly different backgrounds. When Captain Smith realized the boat would likely sink in little more than two hours, he ordered the sixteen lifeboats filled with passengers and lowered into the ocean. The crew and company men knew that fewer than half of the people on board would fit into those boats. They had to make choices about whom to save, which resulted in the “women and children first” rule and was ultimately focused on those in first and second class. The passengers also made decisions, some supposedly fighting for spots, and others giving up their seats.

Manuel Uruchurtu, a lawyer from Mexico who made an appearance in this book, has one such story. He was seated in Lifeboat Eleven when a woman he didn’t know pleaded to be let in because her husband and child were awaiting her in New York. He gave up his seat, only asking that she visit his wife and seven children in Xalapa, Veracruz. Manuel died, but she lived because of his generosity, and twelve years later, she visited his wife in Veracruz and recounted the tale.

Another group that made a huge sacrifice were the ship’s coal workers. The on-duty men in the boiler rooms were the reason the lights stayed on until the Titanic’s final moments; they shoveled coal into the boilers with little or no hope for their own survival. It’s also likely that the off-duty coal workers and engineers assisted the pump operations, selflessly giving others more time to board the lifeboats.

There are so many heartbreaking stories of loss and kindness that it’s impossible to tell them all in a fictional narrative. Not to mention the crew and passengers whose stories weren’t recorded and are lost to us forever. This was something I really struggled with when I first started this book. I knew I couldn’t do justice to all the people I wanted to mention with the space I had. And the more research I did, the more I discovered how many people weren’t given the chance even to fight to survive. Nora, Mollie, and Ada are only a few of these. So in lieu of being able to honor them all, I aimed to highlight the mechanism of social privilege that played a part in who was given priority in the evacuation, and who was not. The working class, the immigrants, those whose cries for help went unanswered, make up the vast majority of the Titanic’s victims. And it’s a social construct that still exists around the world—the privileged receive opportunities that the marginalized do not. While I can’t go back in time and be a voice for the people who were lost the night the Titanic sank, we can all speak up now.