Sixteen hours after the attack on Hiroshima, the White House released a statement from President Truman that outlined more of the Manhattan Project’s history while emphasizing the type of weapon and its power:

With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development. It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East.1

Truman’s statement went on to note that the $2 billion project had been a gamble that the United States had won. “The battle of the laboratories held fateful risks for us as well as the battles of the air, land and sea, and we have now won the battle of the laboratories as we have won the other battles.”

Truman also made more explicit the threat to the Japanese if they did not surrender:

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

As Curtis LeMay would later note, “While the Japanese were trying to make up their minds about what to do, the Twentieth Air Force kept up the pressure.”2 On August 7, LeMay sent a force of 153 B-29s against Japan, and followed it on the eighth with a 375-plane incendiary assault on Yawata.

Japan had fought a brutal war in China for 12 years, and more than three years of war with the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and their allies. The Pacific war brought savage battles, atrocities, and an increasing dedication by Japanese troops not to surrender but to die in battle, taking as many of the enemy as they could with them. It was a bitter, racially tinged, and cruel campaign, and troops awaiting the final decision on whether to invade Japan, especially in the aftermath of the bloody battles for Iwo Jima and Okinawa, welcomed all that the bombings brought. The atomic bomb in particular was viewed as a war-ender, a blow rendered so hard that it would crack Japan’s will to fight.

News of the Hiroshima attack galvanized the troops in the field, especially those training for the seaborne invasion of the Japanese homeland planned for later that year. The arrival of the bomb brought Allied cheers and hope that the war would be over immediately. Paul Fussell, writing about the impact of the news, was a 21-year-old second lieutenant in a rifle platoon, a veteran of the European war training for the final assault on Japan. The thought of not being obliged to “rush up the beaches near Tokyo assault-firing while being machine-gunned, mortared and shelled” brought more than relief; “for all the practiced phlegm of our tough facades we broke down and cried… We were going to live.”3 However, relief would only come after a second attack, as Japan did not immediately surrender.

The second atomic mission was scheduled for August 11, but an impending five-day storm shifted plans. The Destination Team, already working to prepare Fat Man unit F31 for the next atomic attack, was instead asked to shift their efforts and rush work on F33 for a non-nuclear test run.

On the 7th, as the Fat Man assembly team unpacked the ellipsoidal armor steel casings for F33, they quickly discovered that the casings were warped and the bolt holes did not line up. After a frustrating attempt to beat and reshape the casings into fitting, and a failed attempt to enlarge the bolt holes, which only succeeded in injuring one crew member when the bit jammed and threw him to the concrete floor, the team switched to an unused pumpkin’s ordinary steel casing. They fitted it into place and painted it after the high-explosives charges were packed inside. Team member Harlow Russ then added, in black lettering, “JANCFU” on the nose. The first four letters signified “Joint Army Navy Civilian,” he later explained, and “the last two letters had the same meaning as … the standard military vernacular situation description” of SNAFU (Situation Normal, All F****d Up).4

When done, they loaded it into the B-29 ordinarily flown by Captain Frederick C. Bock, 44-27297 “Bockscar,” but on this test flight commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney, the commanding officer of the 393rd. F33’s high explosives successfully detonated when “Bockscar” dropped it off Tinian on August 8. F31 would not prove as easy.

The assembly of F31, just after the struggle with F33, also came with trouble that surfaced when the time came to close up the bomb for the evening. The “dog-tired” team had installed the cable for firing the bomb backwards, so that the plugs at each end were female-to-female and male-to-male. The problem was discovered by Navy ensign Bernard J. O’Keefe, who with an Army technician was left to make the final connections in F31 just before midnight. To fix the error would involve waking the rest of the team and spending much of a day taking the bomb apart and putting it back together again. That was what the protocols for the bomb assembly dictated, but there was not enough time to make the August 9 deadline for the mission. Therefore, “rules or no rules,” O’Keefe, after swearing the technician to secrecy, stripped off the plugs and re-soldered them on the wire in the correct order. He did so, door propped open as he worked, “keeping as much distance between the soldering iron and the detonators as I could…”5 The job completed, he sealed F31 and went to bed.

The next day, the Destination Team, none the wiser, rolled F31 out to the bomb loading pit, carefully balancing the bomb as it bounced on its trailer. Stenciled on the casing, instead of “JANCFU” were a number of signatures and notes, just as there had been with Little Boy. The plane selected to drop the bomb was “The Great Artiste,” commanded by Charles Sweeney, but the decision to go on August 9 found his plane still outfitted with the monitoring equipment for the instrumentation packages it had dropped at Hiroshima. Sweeney and his crew switched planes with Captain Frederick C. Bocks’ crew to once more fly “Bockscar,” this time into combat.

The second strike team was:

• 44-27297, “Bockscar,” loaded with F31;

• 44-27353, “The Great Artiste,” flying as the instrumentation aircraft;

• 44-27354, “Big Stink,” commanded by Major James Hopkins, with scientific observers and photographic equipment. Among the observers were RAF Group Captain G. Leonard Cheshire, a member of the British Military Mission to the United States, the official representative of the British government, and Dr. William G. Penney, whose work on the MAUD committee had led to his participation as one of the “British Mission” at Los Alamos;

• 44-86292, “Enola Gay,” commanded by Captain George Marquardt on this mission, was the advance weather scout for the primary target of Kokura;

• 44-86347, “Laggin’ Dragon,” commanded by Captain Charles McKnight, was the advance weather scout for the secondary target of Nagasaki;

• 44-27298, “Full House,” commanded by Captain Ralph Taylor, was the “strike standby” that would wait at Iwo Jima in case “Bockscar” developed problems and needed to switch planes.

The combat crew of “Bockscar” were Sweeney, pilot Charles D. “Don” Albury, co-pilot Major Fred Olivi, flight engineer Master Sergeant John D. Kuharek, assistant flight engineer Sergeant Raymond Gallagher, bombardier Captain Kermit K. Beahan, navigator James F. Van Pelt, Jr., radar operator Edward K. “Ed” Buckley, radio operator Sergeant Abe M. Spitzer, and tail gunner Staff Sergeant Albert “Al” Dehart. They were joined on the plane by Frederick Ashworth, flying as weaponeer, electronics test officer Philip Barnes, and Lieutenant Jacob Beser, who flew on this mission as electronic counter-measures officer as he had on the Hiroshima strike.

The primary target was Kokura, an ancient fortified town on the straits of Shimonoseki. Kokura, which had been designated as the secondary target for the earlier Hiroshima mission, was the location of the Kokura Arsenal, a vast factory that provided munitions and poison gas for the Japanese Army. The secondary target was Nagasaki, another ancient town, at the southern tip of Kyushu, that had served as a center for commerce, including Japan’s 16th- and 17th-century trade with the Dutch and the Portuguese, and as such the oldest center of Christianity in Japan. It was, as it had always been, an active shipping center, and the setting for a munitions plant that had, among other projects, manufactured the aerial torpedoes Japanese pilots had dropped at Pearl Harbor.

On the evening of August 8, Fat Man F31 slowly rose into the bomb bay of “Bockscar” against “a background of threatening black skies torn open at intervals by great lightning flashes,” according to William L. Laurence.6 Once loaded, the B-29 was towed to the runway and placed under armed guard. Tibbets assembled the crews for a briefing at midnight. William Laurence, present at the briefing, reported that it:

revealed the extreme care and the tremendous amount of preparation that had been made to take care of every detail of the mission, in order to make certain that the atomic bomb fully served the purpose for which it was intended. Each target in turn was shown in detailed maps and in aerial photographs. Every detail of the course was rehearsed, navigation, altitude, weather, where to land in emergencies. It came out that the Navy had submarines and rescue craft, known as “Dumbos” and “Super Dumbos,” stationed at various strategic points in the vicinity of the targets, ready to rescue the fliers in case they were forced to bail out.7

The strike force was to head to Kyushu, rendezvousing at Yakushima, a small volcanic island off the coast, before heading to Kokura. Because of the rough weather, the approach altitude was changed from 9,000 to 17,000ft. A few points made by Tibbets would later come back to plague Sweeney and his crew. He told the crews to wait no more than 15 minutes at the rendezvous before heading on, and he reminded them that the bombardier had to see the target visually in order to drop the bomb. Neither order would be followed.

By 02:15hrs, the flight crews had assembled at the planes, and last-minute checks were underway when Master Sergeant Kuharek, the flight engineer, pointed out to Sweeney that a fuel transfer pump was not working properly. Accounts differ as to whether it was not functioning at all, or required hand-pumping, but the pump was a serious problem. According to “Don” Albury, the co-pilot:

Most B-29s carried a 600-gallon reserve fuel tank in the aft bomb bay. The gas tank was mainly used for ballast, and I don’t recall ever having to tap into it on earlier missions. Unfortunately, the fuel-transfer pumps were not working, and the 3,600 pounds of fuel in the back became dead weight. Maj. Sweeney exited the aircraft, and he and Col. Tibbets had a lengthy discussion about the problem. Ultimately, Sweeney made the go decision… Things only got worse from here.8

Nearly an hour behind schedule, the mission got underway. The weather planes took off at 02:58hrs, followed by the strike force. “Bockscar” lifted off at 03:47hrs. “The Great Artiste” followed at 03:51hrs, and “The Big Stink” at 03:53hrs.

The planes headed northwest into the storm. On “The Great Artiste,” “we were about an hour away from our base when the storm broke,” William Laurence later wrote. “Our great ship took some heavy dips through the abysmal darkness around us,” and then Laurence noticed “a strange eerie light coming through the window.” Staring out into the night, he saw that “the whirling giant propellers had somehow become great luminous discs of blue flame. The same luminous blue flame appeared on the plexiglass windows in the nose of the ship, and on the tips of the giant wings it looked as though we were riding the whirlwind through space on a chariot of blue fire.”9 Static electricity bathed the plane, and Laurence worried that it might detonate the bomb. He was reassured that it would not.

Meanwhile, on “Bockscar,” Frederick “Dick” Ashworth had crawled aft at 04:00hrs to switch the safe/arm plugs and arm the Fat Man. Back at his station, he watched the control panel with Barnes. An hour later, around 05:00hrs, the first light of the dawn appeared in the sky, and just before 06:00hrs the sun was up. The planes continued on for another three hours, approaching the rendezvous. There, another problem surfaced as “Bockscar” waited for the other planes:

“The Great Artiste” found us right away, and we circled waiting for “Big Stink” to show up. We were making small circles at 30,000 feet, and unbeknown to us, it was making big wide circles at 39,000 feet. We never saw one another, and after 40 minutes, “Bockscar” and “The Great Artiste” jumped on the Hirohito Highway and headed for Japan.10

On “The Great Artiste” Captain Bock reportedly spotted the “Big Stink,” but Sweeney did not, later claiming, as did Albury, that the other B-29 was flying much higher than it was supposed to.

Major Hopkins had flown off without scientist Robert Serber, the only person trained to operate the high-speed camera that was to document the blast. In his haste to board, Serber had failed to grab a parachute, and Hopkins, while taxiing down the runway, ordered the crew to kick Serber off the plane. That, the scientist noted, “was truly idiotic … the plane was supposed to have a mission … to take pictures.”11 Instead, with the plane’s engines revving, Serber was pushed out of a hatch and left in the darkness at the end of the runway. Hopkins’ stubbornness infuriated Tibbets and the other senior officers when to their surprise Serber walked into their hut an hour later, but “Big Stink” was already gone, operating with the other B-29s on radio silence. Because Serber alone knew how to operate the camera, radio silence was broken for Tibbets to give Hopkins “a little piece of his mind” and for Serber to relay instructions, but in vain. The camera was never used because it was too difficult for the crew to operate.

The weather planes reached Kokura and Nagasaki and reported that while there was cloud cover there was enough visibility to proceed, and so “Bockscar” and “The Great Artiste” departed for Kokura without “Big Stink.” At 10:20hrs, the planes arrived to find that smoke drifting from fires at Yawata, a steel mill town firebombed a day earlier, obscured the target. Sweeney made three passes over Kokura, but each time, Beahan reported he could not spot the aiming point. As Japanese aircraft and flak gunners drew closer, it was time to go. At 11:32hrs Tinian time, after 45 minutes over Kokura, “Bockscar” and “The Great Artiste” diverted to Nagasaki. To this day, the Japanese still speak about the “luck of Kokura.”

Fuel was low on “Bockscar,” and Sweeney and Albury determined that they could make only one pass over Nagasaki. They flew into clouds formed by a weather front blowing in from the East China Sea, and Nagasaki, earlier reported as clear, was now covered by drifting clouds. Sweeney did not want to make the decision to attack alone, and called Ashworth forward. After discussing whether to bomb using radar, with Ashworth initially against it, the weaponeer finally relented. Jacob Beser later commented, “there was no sense dragging the bomb home or dropping it in the ocean.”12 Lining up from their initial point, the crew flew “Bockscar” on a radar approach for 90 percent of the run, until suddenly Beahan shouted that he could see the city through the clouds. It was 11:01hrs Nagasaki time. Switching to visual, Beahan took control the plane and triggered the bomb’s release at 28,900ft.

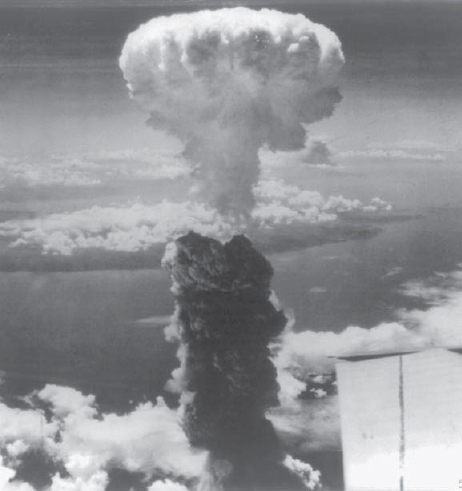

A cloud of smoke and dust punches into the sky above ground zero at Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The cloud rose 11 miles into the atmosphere before dispersing. Reporter William L. Laurence, watching from a nearby plane, described it as “a flower-like form, its giant petal curving downward, creamy white outside, rose-colored inside. It still retained that shape when we last gazed at it from a distance of about 200 miles.” Laurence also described the cloud in a term more familiar to most, "a giant mushroom." Poetic descriptions aside, the cloud from a distance obscured the effects of the blast and heat on the city below. Tens of thousands of people had just died in a matter of seconds. (USAAF photograph, Library of Congress)

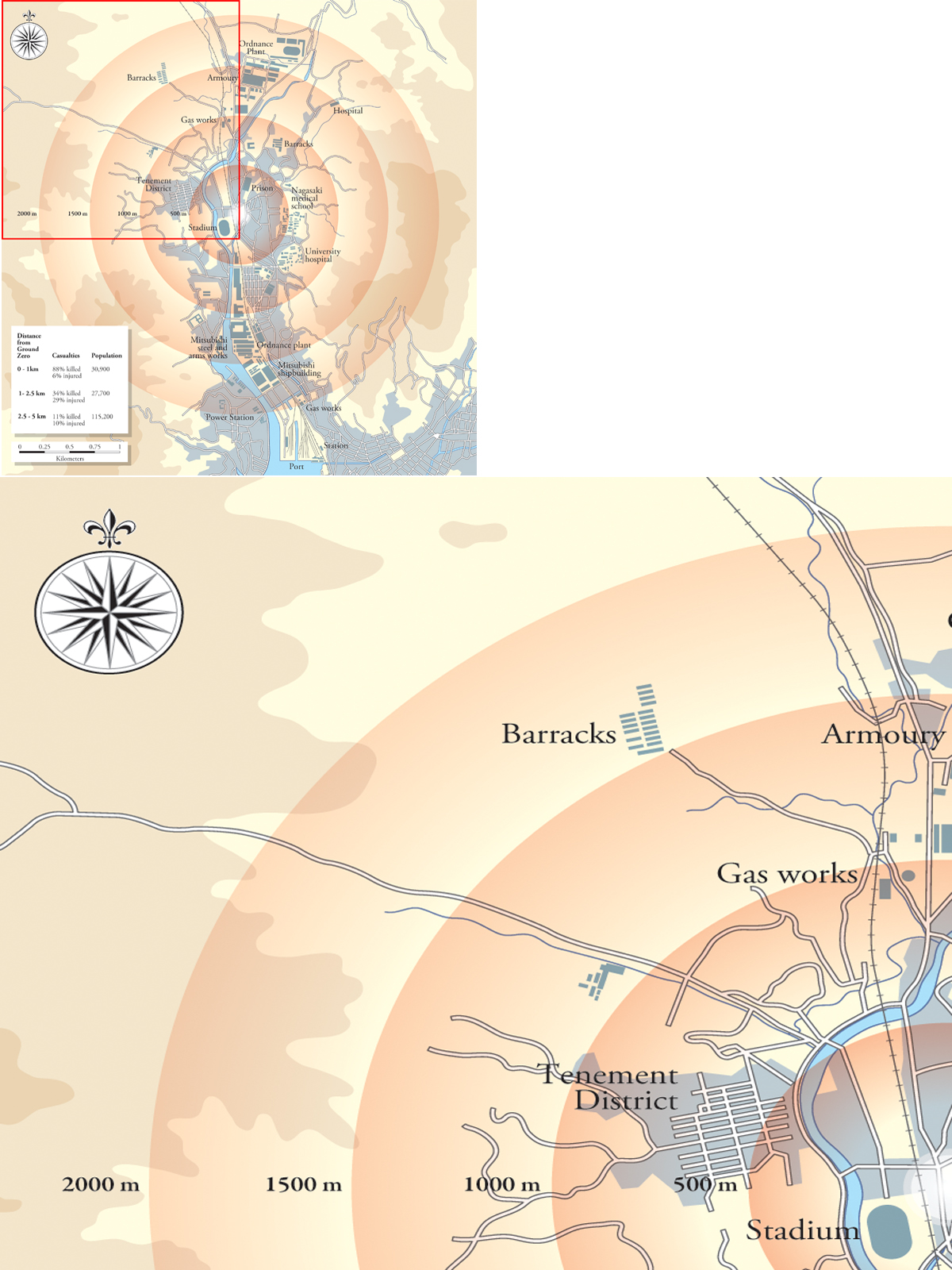

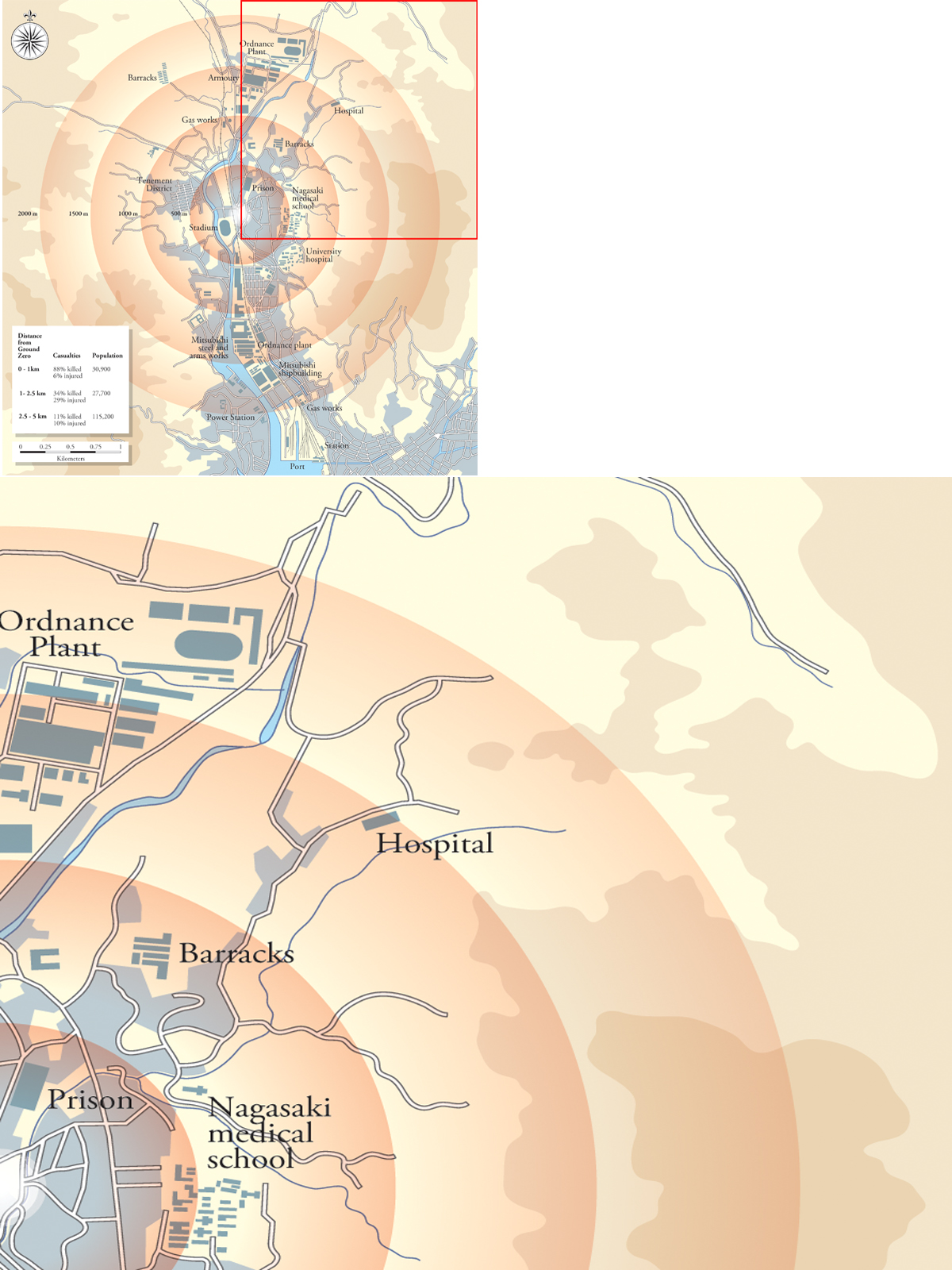

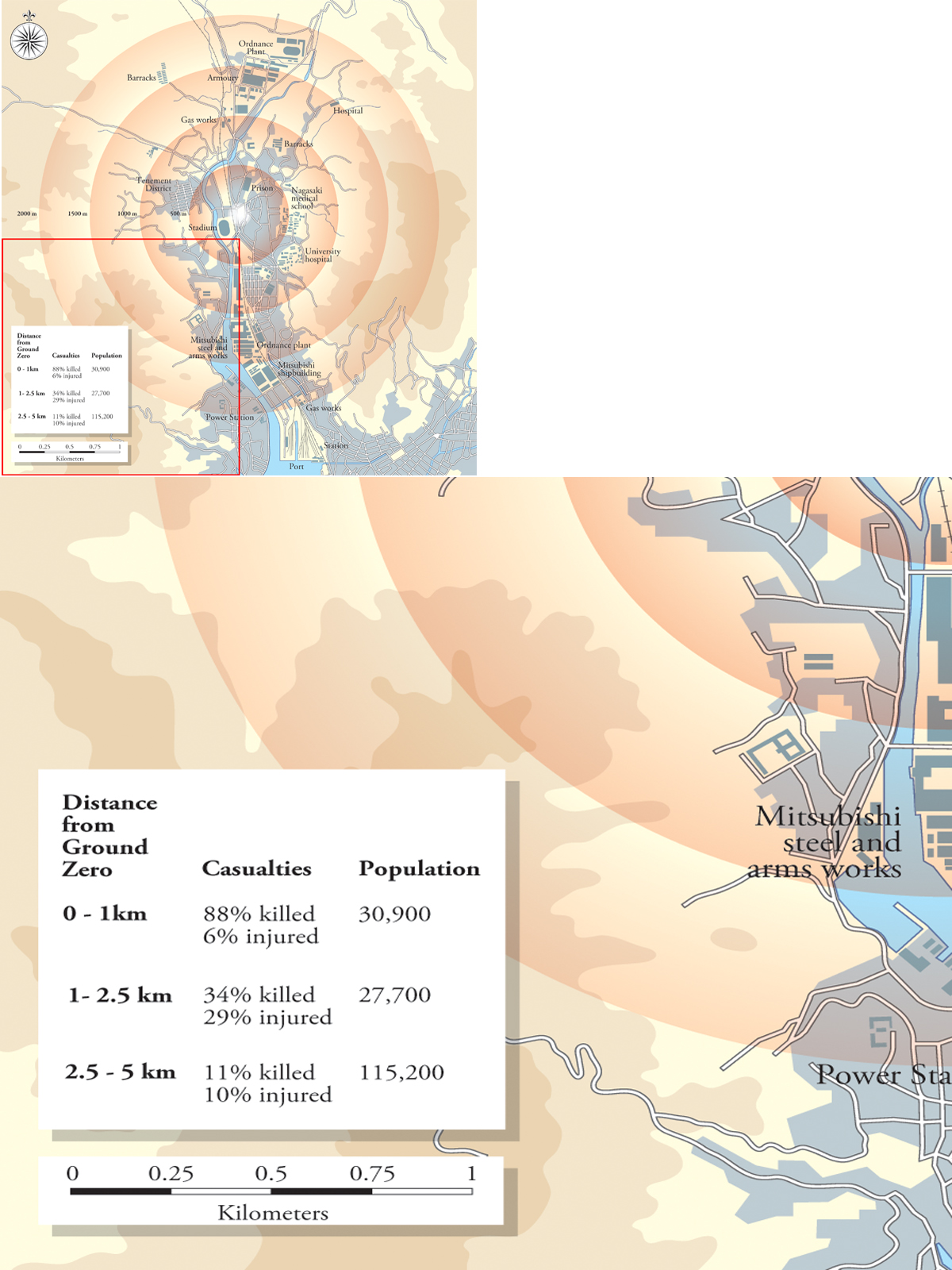

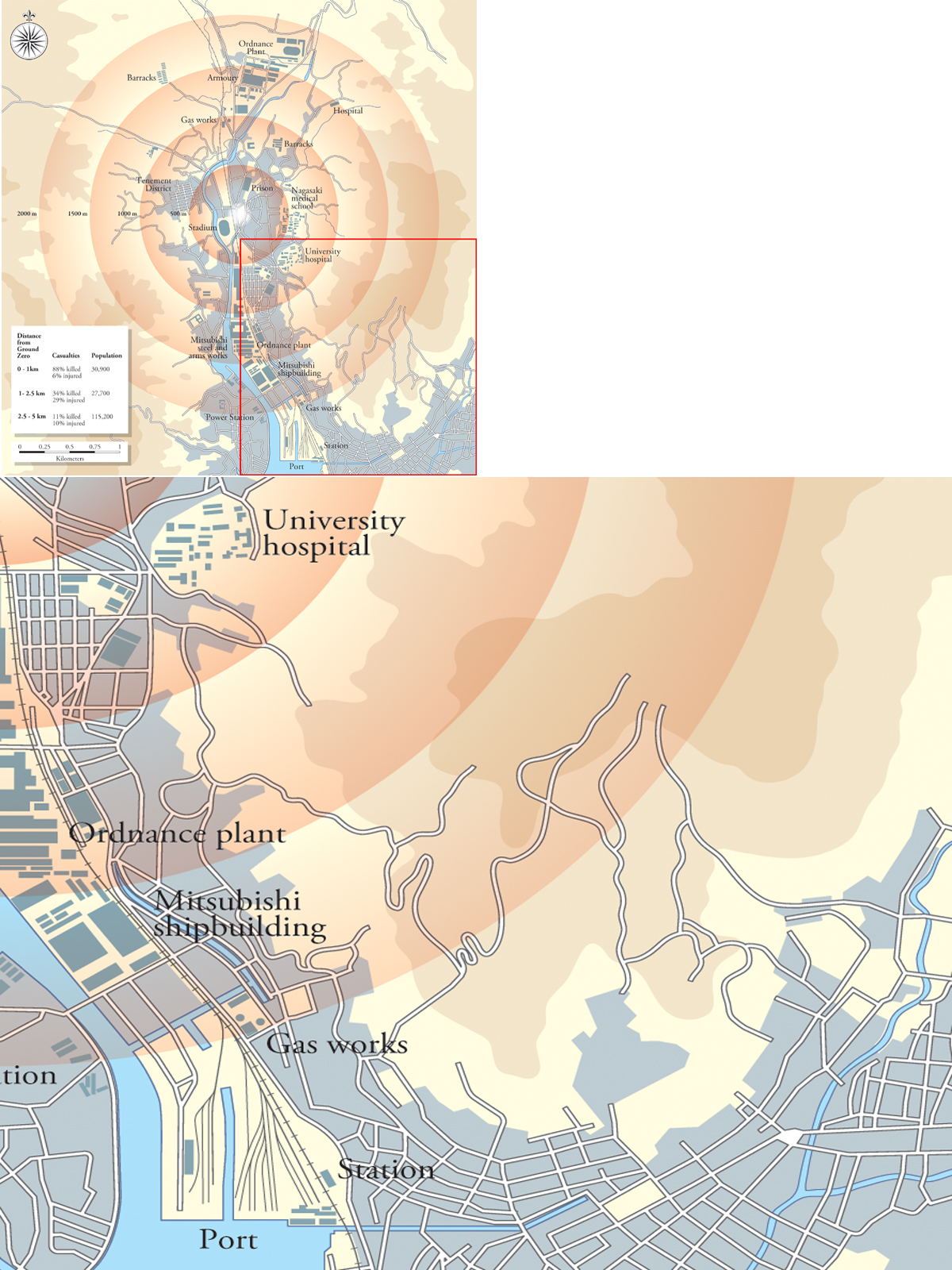

Following on “The Great Artiste,” William Laurence, who on the flight had mused, “Does one feel any pity or compassion for the poor devils about to die? Not when one thinks of Pearl Harbor and of the death march on Bataan,” watched as “out of the belly” of the other plane “what looked like a black object came downward.”13 The crews had pulled their dark glasses over their eyes, and as Fat Man dropped, they counted. Forty-seven seconds later, F31 detonated 1,650ft above Nagasaki’s industrial district. It was off target, as Beahan’s last-minute glimpse through the clouds had come too late to drop the bomb accurately. The Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works, where the Pearl Harbor torpedoes were built, took the brunt of the 21-kiloton blast. The explosion swept through the Urakami Valley, the center of Nagasaki’s Christian (Catholic) population and site of the Catholic Cathedral. The surrounding hills shielded much of Nagasaki’s other residential districts.

The Fat Man was approximately 40 percent more powerful than Little Boy at 21 versus 15 kilotons. The fireball grew as intense as 7,000°F (3,900°C) and obliterated everything living within a 0.6-mile diameter. High winds caused by the blast tore through the city at over 600mph, and the bomb’s blast-induced overpressure collapsed concrete buildings and reduced wooden buildings to kindling, just as the blast did at Hiroshima. The detonation devastated everything within a 1.2-mile area, with many casualties from flying glass and debris as well as the heat. In all, between 40,000 and 75,000 people died, and as many as 75,000 were injured by the heat, blast, and radiation, according to a 1950 report by the City of Nagasaki.14

The Nagasaki bomb detonated off target (approximately 2 miles away from the planned hypocenter) over Nagasaki’s Urakami Valley. The hills that surrounded the valley partially sheltered the rest of the city from the effects of the blast. However, the pressure and heat left a radius of near total destruction of some two miles, and between 40,000 and 70,000 people died instantly. (Ira Clarence Eaker Collection, Library of Congress)

In the air, Laurence noted that after the initial flash, a bluish-green light still filled the sky as “Bockscar” and “The Great Artiste” sharply turned and dived. A shock wave hit the planes, making them “tremble from nose to tail. This was followed by four more blasts in rapid succession, each resounding like the boom of cannon fire hitting our plane from all directions.” Looking down:

Observers in the tail of our ship saw a giant ball of fire rise as though from the bowels of the earth, belching forth enormous white smoke rings. Next they saw a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000 feet high, shooting skyward with enormous speed. By the time our ship had made another turn in the direction of the atomic explosion the pillar of purple fire had reached the level of our altitude. Only about 45 seconds had passed. Awe-struck, we watched it shoot upward… As the first mushroom floated off into the blue it changed its shape into a flower-like form, its giant petal curving downward, creamy white outside, rose-colored inside. It still retained that shape when we last gazed at it from a distance of about 200 miles.15

There was not much time to linger. “Bockscar” was low on fuel, and after four minutes of observation, the two planes began to head for their emergency landing point, the recently conquered island of Okinawa. Sweeney and Albury worried that they might not have enough fuel to make it, and radioed ahead to alert rescue forces to the fact they might have to land in the sea. Meanwhile, the missing “Big Stink” arrived over Nagasaki, too late to capture the fireball, but in time to photograph the plume of smoke that boiled up from the stricken city. “Big Stink” then headed for Okinawa. All the way, the pilots nursed “Bockscar” along, praying they would make it.

After an hour’s flight, the island was in sight. Attempts to raise the tower by radio failed to receive an answer – Okinawa was in the middle of an alert and a number of planes were trying to land at Yontan Field. Sweeney ordered emergency flares fired from the plane, to no effect, and so he ordered every available flare shot out, making “Bockscar” a huge Roman candle as it cut between two planes, one landing, another on final approach, slamming down on the runway at 150mph, 30mph faster than the recommended landing speed. According to Albury:

At 500 feet, our number-three engine began to suck air, and we felt the effects immediately. Maj. Sweeney and I were too busy even to curse as we fought to control Bockscar’s descent. As we touched down, the number-two engine gasped and coughed for the last time as it, too, was starved of fuel. Sweeney and I slammed on the brakes and threw the two running engines’ propellers into full reverse. We stopped 500 feet from the end of the runway, and our clock showed it was 1pm. That was the longest nine hours and 11 minutes of my life!16

Twenty minutes later, “The Great Artiste” and “Big Stink” also landed at Okinawa. When the crew checked the fuel tanks on “Bockscar,” other than the unusable 600 gallons in the tail, the B-29 had only 33 gallons left in the tanks. It had been a very close call.

After refueling, and surveying the planes for damage, the Nagasaki strike force took off after a four-hour layover from Yongan Field. They landed at Tinian, hours overdue, at 11:30hrs to a subdued reception. No crowd, fanfare, or medal ceremony as had greeted the crew of “Enola Gay” awaited Sweeney and his crew. They posed for a few photographs and headed off for debriefing. Harlow Russ later commented that the JANCFU acronym he had painted on F33 had been “intended to be facetious, not a prediction.”17 However, there were no public recriminations, and commendations and promotions were forthcoming, although public acclaim and fame never followed the crew of “Bockscar” as it did for that of “Enola Gay.” The Nagasaki attack, as a follow-up, never attracted as much attention, even for its survivors and their ordeal.

In Nagasaki, the explosion caught many people by surprise as the mid-day preparations for lunch were underway. Others, alerted by air raid sirens, were taking shelter. Fifteen-year-old schoolgirl Michie Hattori was standing in the entrance to her High School’s air raid shelter, “motioning for the pokey girls to come in. First came the light – the brightest light I have ever seen.” Temporarily blinded, Hattori was hit by a “searing hot flash... For a second I dimly saw it burn the girls standing in front of the cave. They appeared as bowling pins, falling in all directions, screaming and slapping at their burning school uniforms. I saw nothing for a while after that.”18 The force of the blast then threw Hattori into the shelter and promptly blew her back out again.

Nagasaki atomic damage and casualties, August 9, 1945. This map is based on the US Strategic Bombing Survey’s map (1946). (Artist Info)

When she regained her sight, Hattori and other survivors made their way toward the school through fires that had started in fallen houses. “Thick smoke and dust filled the air. The fires gave the only real illumination.” Hattori heard some of the other girls repeat “jigoku,” the Japanese word for hell. They came across a badly burned person crawling in the road. “No clothes or hair were visible, just large, gray scalelike burns covering its head and body. The skin around its eyes had burned away, leaving the eyeballs, huge and terrifying. Whether male or female I never found out.” The victim begged for help, then died.

Survivors made their way to the Urakami River, only to find hundreds of the dead and dying by the river banks and in the water, just as had happened at Hiroshima. Another survivor, 10-year-old Shimohira Sakue, saw “a large number of people at the banks of the river. They were scorched black and struggling to get a sip of water, but most of them died right there on the bank. Hundreds of dead bodies were caught on the rocks in the river.”19 Walking toward her home to find her family, Sakue found the “city was so devastated that we could not even tell where our house had been. All that was left was a field of rubble scattered with blackened corpses.” When she reached home, she found her family there had been killed:

When we finally found the ruins of our house, we dug through the rubble until we found a corpse burnt beyond recognition. The hands were still covering the eyes, with the thumbs plugging the ears. Because the skin underneath was intact, we found when we pulled away the hands that it was our older sister. After that we gathered debris from the ruins of the house and used it to cremate the body. No matter how hard we searched, though, we couldn’t find our mother in the rubble. Finally we checked two bodies lying out on the street, and we identified one as our mother by her capped tooth. We had no container for the ashes after the cremations, so we used a blackened kitchen pot to hold the remains of both my mother and sister.

Sakue’s older brother, who was farther away from the blast, reunited with her, apparently unhurt. But radiation sickness soon revealed itself. He “began to spit out huge amounts of a yellow liquid. He died later crying that he wanted to stay alive.” In this and many other cases, survivors seemingly untouched manifested terrible symptoms within hours, days, weeks, and in time, years after the detonation of Fat Man over Nagasaki.

Following the bombing of Nagasaki, the Twentieth Air Force continued to drop leaflets on Japan urging the surrender of the Japanese government. In Tokyo, government leaders were considering surrender, but militarists were urging that the fight continue, hopeful that the Soviet Union, which had remained neutral in the war with Japan, would help negotiate a peace different from the unconditional surrender demanded in the Potsdam Declaration. Those hopes were dashed in Moscow on August 8, when Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov called in Japanese Ambassador Naotake Satō, and told him that:

Taking into consideration the refusal of Japan to capitulate, the Allies submitted to the Soviet Government a proposal to join the war against Japanese aggression and thus shorten the duration of the war, reduce the number of victims and facilitate the speedy restoration of universal peace. Loyal to its Allied duty, the Soviet Government has accepted the proposals of the Allies and has joined in the declaration of the Allied powers of July 26. The Soviet Government considers that this policy is the only means able to bring peace nearer, free the people from further sacrifice and suffering and give the Japanese people the possibility of avoiding the dangers and destruction suffered by Germany after her refusal to capitulate unconditionally.20

The Soviets told the ambassador that as of the following day, August 9, they were at war with Japan. At dawn, a massive Soviet assault of over a million and half troops rolled into Japanese-occupied Manchuria, and in a double pincer movement met up at Changchun, cutting off a Japanese retreat into Korea. Over half a million Japanese were taken prisoner.

The Japanese government, on August 10, sent word that it would surrender under the terms of the Potsdam Declaration with one condition, that surrender not “prejudice the prerogatives” of the Emperor. As the United States weighed a compromise, which would leave the Emperor in place but place him under the authority of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, the US government also decided to keep the war “at its present intensity” until the Japanese surrendered. In Japan, a faction of military officers plotted to keep the nation from defeat, even if it meant sacrificing 20 million lives in a national kamikaze-style suicide attack or through a coup d’etat to prevent the Emperor from surrendering.

On August 10, General Spaatz sent a cable urging a third atomic attack on Tokyo. Groves the same day reported to General of the Army George Marshall that another bomb would be ready for a mission on August 17 or 18. “Jabit III” had already been dispatched to Los Alamos for another plutonium core on August 9, and at Tinian the Destination Team had begun work prepping three practice Fat Man units for test runs. A third combat unit was problematic, despite having components on hand, because the high-explosive assembly had cracked and the bomb had untrustworthy high-explosive cast clock that might not detonate properly. Also there were no detonator chimneys, specially machined lengths of brass tubing, glued into place, that allowed the team to insert and line up the detonators to the exact centre of each lens. This created a “semi-panic,” as Harlow Russ later recalled. The clever scientists, engineers, and technicians, using raw material provided by a helpful naval vessel, were able to solve the detonator chimney problem, manufacturing new ones from brass.

In answering Groves, General Marshall had approved preparations for a third attack, but reminded him that “It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President.”21 Truman, mindful of the fact that the Japanese were debating surrender, had ordered a halt to the atomic attacks, aware of the civilian toll and not happy with the thought of killing “all those kids,” as he confided to Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace.22 However, atomic attacks would resume if the Japanese did not surrender.

While Groves, the President and his cabinet, especially Secretary of State Byrnes, considered the role of the bomb as a war-ending strategic tool, debate in the War Department over continued use of the bomb focused on its tactical role:

The problem now is whether or not, assuming the Japanese do not capitulate, to continue dropping them every time one is made and shipped out there or whether to hold them ... and then pour them all on in a reasonably short time. Not all in one day, but over a short period. And that also takes into consideration the target that we are after. In other words, should we not concentrate on targets that will be of the greatest assistance to an invasion rather than industry, morale, psychology, and the like? Nearer the tactical use rather than other use.23

On August 12, as debate consumed two governments, the military forces of Japan and the United States re-commenced hostilities after a brief lull in the fighting. The Twentieth Air Force responded to renewed Japanese attacks by launching more raids against Japan on the evening of the 13th. On August 14, nearly a thousand planes arrived in the skies over Japan. Thousands of tons of bombs rained down in Hikari, Osaka, Marifu, Kumagaya, and Isezaki, the latter two hit by incendiaries as well as high explosives. Other planes dropped mines in the Straits of Shimonoseki and in harbors.

The debate in Japan continued even after the Emperor decided to surrender. A military coup that seized the Imperial Palace in an attempt to stop the broadcast of the Emperor’s surrender failed on the evening of August 14, and at noon the next day, the Emperor spoke to his subjects by radio, telling them he had resolved to end the war “by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is insufferable.”24 In reality, his subjects and the victims of Japanese aggression had already suffered, with over two million Japanese dead and millions of Allied casualties, many of them Chinese. Most of Japan lay in ruins, its armies defeated even though Japanese forces continued to fight on in Manchuria, and its navy and merchant marine were for the most part at the bottom of the sea.

In his speech to the nation, Hirohito specifically mentioned the weapon that had helped push Japan to surrender:

Moreover, the enemy now possesses a new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.25

The bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki had played a powerful psychological role, to be certain, in the end of the war, but they had not won the war. That much was clear to the Army, Army Air Forces, the Navy, and Marine Corps, all of whom had fought a bitter and sustained series of campaigns across the Pacific to victory. While the atomic bombs had not played a major role in combat, however, the unleashing of atomic power had a profound impact, with civilization-altering implications for the postwar world.