LORD MACARTNEY’S DISPLEASURE

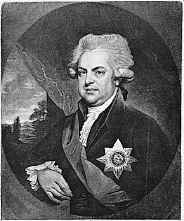

Lord Macartney, from a portrait by Mather Brown, 1790

Madras, 13 January 1782

While Hosea was still chafing against the delays to his departure from Calcutta, the Grosvenor dropped anchor off Madras. Captain Coxon was to take on most of his passengers here and his spirits rose. An early sailing was in prospect, for his duties to the Company’s war effort had been discharged and by agreement he was to be released from any further obligation within a month.

The sooner the better, so far as Coxon was concerned. Madras was a place of evil reputation among seamen. Unlike Calcutta, it had no natural advantages as a port and although it was the oldest British settlement in India – construction of Fort St George had begun in 1640 – nothing had ever been done to endow Madras with a pier. Vessels anchored offshore so that passengers had to be ferried to and from their ships in native craft through notoriously rough surf. Spills and accidents were commonplace, but it was not just for the perils of the landing that the place was infamous. Ships anchored in Madras Roads were regularly dashed to pieces by typhoons, with grievous loss of life and cargo.

The Grosvenor’s cargo of rice for the garrison was offloaded without mishap, but Coxon’s hopes of an early departure were disappointed. Although the captain of an independent ship, and so nominally responsible only to the owners, he was in the jurisdiction of the Company – in this instance the Madras board – and a month later he was still awaiting sailing orders. Like most sea captains, Coxon was impatient of outsiders who interfered with the smooth running of his ship and at this stage he rashly fired off a letter to the board, pointing out that the contract between owner and Company had expired and, ‘the Grosvenor not yet being despatched’, the Company would be held responsible for compensation. He also served notice that he would sail for England regardless at the end of thirty days.

This broadside brought a placatory reply: that authorisation to depart would be ready within ten days; but Coxon’s letter had been a high-handed bluff and Lord Macartney, the local Governor, knew it. Macartney was not a good man to antagonise. An imperious patrician with powerful connections, his influence in the Grosvenor saga was to be potent at a number of points in the years ahead, and without exception baneful. His first intercession, evidently intended to teach Coxon a lesson, was to see to it that his departure was delayed.

Over the next two weeks cargo was ferried out to the Grosvenor as she lay at anchor in Madras Roads. The bulk of it was described in the official record as ‘coast goods’. As well as the silk bales being transported by the nabobs Williams and Taylor, and Hosea’s freight of indigo, this included textiles and sugar. A proportion would have belonged to Coxon – as captain he was entitled to carry 38 tons of goods on the homeward voyage for his own private trade – and his officers. The local value was stated as being about £60,000. Its value on being landed in England would have been around £300,000 – today about £18 million. Gold and diamonds, the transportable wealth of passengers and officers, were also being carried. Manifests show that the gold was in the form of small coins, called star pagodas, and had a total value of £65,000; the diamonds were worth £10,000 locally, considerably more in England.

On 27 February Coxon wrote again to the board, saying that the Indiaman was loaded and ready to set sail. Having been told that he would be cleared for departure by 21 February, he was becoming worried as well as frustrated. The season of a voyage was crucial to its duration and safety and the optimum time for taking advantage of the north-east monsoon – between January and February – had already passed. Unless he left within two weeks, Coxon knew, his progress would be slowed by southerly winds. From April he would run into the south-west monsoon winds, with all their delaying effect.

In response to his more emollient tone, the board issued orders ‘that Captain Coxon be directed to keep the Grosvenor ready to proceed on the shortest notice’. But the harm had already been done. Soon afterwards news was received that a great French fleet had arrived off the coast, and all merchant departures were halted. Not for another month would the Grosvenor be allowed to sail.

Coxon was not the only one fulminating against the board. If one thing united those taking passage on the Grosvenor, it was their common desire to be quit of India. Hosea’s motives were deeply hidden. Those joining the ship in Madras could be more honest about their fears: not for the first time in the city’s history, a marauding army was at its gates.

Madras, founded by the British on the supposed site of St Thomas’s martyrdom, was yet to be reconciled to the administrative ascendancy of Calcutta. Had not Madras, in the shape of Clive and his army, won Bengal? Neoclassical residences on the seafront testified that local traders could match their Calcutta counterparts for stylish living, and St Mary’s was the oldest Anglican church in India. The traders, with their connections going back to the Company’s earliest ventures among the Spice Islands, liked to refer to themselves as ‘the gentlemen of The Coast’, although the nature of their business with the local ruler, the Nawab of Arcot, was anything but gentlemanly.

Now though, as in Clive’s time, the tenor of life was dominated by the military. A year earlier, Hyder Ali, the Sultan of Mysore, had inflicted a catastrophic defeat on British arms at the village of Pollilur, several days’ march away. This astonishing reverse ‘engaged the attention of the world’, in the words of the Prime Minister, Lord North. More particularly, it engaged the residents of Madras, who had witnessed Hyder’s cavalry thundering into the suburbs, ‘surrounding many of the English gentlemen in their country houses who narrowly escaped being taken’.

Coxon found himself besieged by applicants for passage to England. Since he had named his own price to Hosea and the nabobs, the demand for space on the Grosvenor had, if anything, increased. Of the two other Indiamen due to sail before the end of the season, the Rochford was found to be leaking and declared unseaworthy, while the Earl of Dartmouth had yet to leave Calcutta. The opportunity for lining his purse with passage money was too good for Coxon to pass up. On her previous voyage home, the Grosvenor had carried thirteen passengers, which was rather more than average for an East Indiaman of her size. When she set out on her last journey, crammed into the great cabin, the roundhouse and the forward quarters were thirty-one European passengers – from officials, traders and military men, to wives, children and servants.

Among them was the singular figure of Charles Newman.

Newman was a lawyer in Calcutta, a jurist able enough for his colleague and near-contemporary William Hickey to note that he had ‘made a fine fortune by his profession’. He was a dandy, with a fondness for silver possessions bearing his monogrammed initials, whether his personal cutlery, the buckles of his shoes, or the buttons on a green broadcloth coat that he wore on his appearances in court. Aged in his mid-thirties, with a wife and child, he was also close to Hastings. In the intrigues that divided the Company’s affairs, Newman was among the few whom the Governor could unequivocally call ‘my own agents’.

He had come to prominence in the most sensational scandal in Bengal’s history. Three years earlier, on the night of 8 December, 1778, no less a figure than Hastings’s old enemy Philip Francis had been apprehended with a bamboo ladder outside the house of George Grand, a lowly Company writer. Grand was not at home, but his wife, by consensus Calcutta’s greatest beauty, was in an upper room. The former Mademoiselle Noel Catherine Werlee, not yet aged twenty, was a creature as exotic as she was ravishing, with what one scribe was moved to describe as ‘the stature of a nymph, a complexion of unequalled delicacy, and auburn hair of the most luxuriant profusion.’ There was a hint of the Orient to her features, which enraptured the French; Napoleon callied her ‘Anglaise ou Indienne’. The Bengal artist Zoffany celebrated her in paint, and Francis was far from being her most prominent lover. Grand, however, who had wed her before she was fifteen, was sufficiently outraged to take the issue to the Supreme Court, claiming the fantastic sum of 1,600,000 rupees (£160,000) from Francis for having deprived him of the ‘solace, affection, comfort and counsel’ of his wife.

Newman had acted for the injured husband in a case that transfixed Calcutta for months. In forensic manner he had led Grand’s servants through their evidence: the kitmugar, who had found the ladder against the window of Mrs Grand’s bedroom; the jemadar, who had seen Francis coming out of the house and detained him; and the bowanny, who had told of Mrs Grand trying to order Francis’s release (to which the jemadar had replied: ‘I will not hear you, you may go to your room.’). Newman had extracted testimony to show how Francis had first blustered – ‘Do you not know me? I am the Burra Sahib’ – then tried to bribe his way out of the situation – ‘I will give you money. I will make you great men’ – before fleeing.

It says something for Newman’s powers that he persuaded a three-man Bench to accept the word of native witnesses rather than the most powerful man in Bengal after Hastings, despite the intercession of Sir Robert Chambers. Although the judges assessed the figure placed by Grand on his wife’s virtue as a touch on the high side, he was awarded 50,000 rupees (£5,000) against Francis. One of the three dissented, Chambers finding that adultery by his crony was not proven. The Calcutta chronicler H. E. Busteed noted laconically: ‘Without in the smallest degree insinuating that the Chambers dissent was influenced by [non-legal] considerations, it may be pointed out that long before the trial he and Francis were the closest official allies, if indeed not something more.’

Francis then rather undermined his friend’s judgment by installing Mrs Grand as his mistress, but the arrangement did not last. After Grand divorced her, she found another protector before sailing for Europe, where she continued to dazzle powerful men and eventually sealed a heart-warmingly improbable career by becoming the wife of the French statesman Prince Talleyrand.

Newman’s ability, and no doubt his humiliation of Francis, had meanwhile caught the attention of Hastings, who started to assign him delicate diplomatic tasks. One such mission had now brought him to Madras.

For years concerns had been growing at the Company’s headquarters in Leadenhall Street about business practices in the southern presidency that went beyond mere peculation and profiteering. The Madras gentry were bound so deeply to the Nawab of Arcot by a mutually dependent system of loans and patronage that their interests no longer converged with those of the Company. This buccaneering clique, known as the ‘Arcot Interest’, had undoubtedly encouraged the Nawab to plunder neighbouring rulers, but were also suspected of selling intelligence about British military deployments to the French settlement at Pondicherry. Worst of all, the Arcot Interest was reputed to own a vessel named the Elizabeth, which was sailing under French colours while engaging in piracy against British shipping off the eastern, or Coromandel, coast. The main suspect was none other than Sir Thomas Rumbold, Hosea’s old patron, who had recently retired as Governor of Madras and returned to England with a fortune breathtaking even by the standards of the Orient. Suspicion had also fallen, however, on his successor, Macartney.

Newman arrived from Calcutta in November 1781 with orders to collect evidence against Rumbold and other Company servants who, in the words of the directors, ‘are supposed to have unwarrantably acquired large sums of money contrary to law and their own solemn engagements’. Hastings’s private instructions were for Newman to get to the bottom of the Arcot Interest’s treachery.

At first Macartney made a show of cooperation. Newman was invited up to Fort St George to meet the Madras board, who ‘handsomely flattered me with assurances of every assistance in their power’; but his questioning of officials was met with blanket professions of ignorance. He tried to speak to Macartney’s durbash, his interpreter and go-between in dealings with the Nawab, but the durbash fobbed him off. Rumbold’s former durbash was equally obstructive. When Newman appealed to Macartney, he was told that the Governor had not ‘weight sufficient to prevail on [the interpreters] to give evidence’.

Newman’s suspicions grew when he attended a session of the board at which a letter from the Nawab was read out in which he too declined to assist the investigation, and the board hailed him ‘for refusing to turn informer’. With growing exasperation, Newman tried to appeal over Macartney’s head. He issued a public notice, asking for information about fifteen named Madras citizens said to have received from the Nawab sums of between £10,000 and £40,000 ‘for bringing about the Revolution of 1776’.* In this astonishing episode, Lord Pigot, an earlier Governor appointed by the Company to deal with the Arcot Interest, was arrested by his councillors and died suddenly in their custody. That outrage had never been punished but, on hearing about Newman’s public notice, Macartney objected that it was irrelevant to his investigation.

Newman was ill with a fever, he was being kept at arm’s length by Madras society, and he was a long way from his family in Calcutta. His attempts to obtain information were being frustrated at every turn. At some point, however, he started to receive information. On 1 February he wrote to Macartney; referring to the pirate ship operating under French colours, he said it was ‘notoriously spoken of in the settlement as true . . . that the Elizabeth did belong to one of the gentlemen of this place’. He had found, nevertheless, that ‘the spirit is so much against enquiries that those few who could and would give information on the subject dare not stand forth because they would be condemned by the settlement at large.’

This bombshell elicited a reply from the board’s secretary that took issue with ‘the general style of your letter, as well as some particular passages’ and objected to ‘a strong disposition in you to lay at their door the ill success of the enquiries committed by the Directors to your charge’. Newman replied on 13 March; with declamatory flourishes that would have graced his old courtroom, he declared that he would not accept ‘blame which I conceive to rest with you [Macartney]’. He scorned the board’s claim to have done all in its power to get to the bottom of the scandals:

I can not, nor will others who know what the influence of a Governor is in India over durbashes, join in the Idea that the Board [is unable] to prevail upon them to give evidence.

Challenged to prove a conspiracy, he drew himself up: ‘Do the Board seriously expect that I should comply with this requisition? May not [this] form a part of that evidence which is to be transmitted only to the Secret Committee of the Hon’ble Company? And might not the discovery be making those persons from whom I derive my knowledge [into] victims?’

This hint that he had come upon damning evidence seems at last to have caused a flicker of panic in Madras. The board’s final letter to him before it cut all communication denounced his manner as ‘disrespectful and improper’ and vowed to make representations to the Secret Committee, trusting that it would receive ‘that justice which has been in vain expected from Mr Newman’.

Now Newman determined on action. There could be no question of returning to Calcutta. He would sail for England to lay his evidence before the directors. So he called on the captain of the sole Indiaman in port, John Coxon, and impressed on him the urgency of his mission; and further space was found in the Grosvenor’s crowded passenger quarters.

Macartney had at last tired of toying with Coxon. On 27 March orders were issued for the Grosvenor to join a Royal Navy squadron recently arrived in Madras and to sail under its protection towards Ceylon. There she was to await the Earl of Dartmouth or, failing her arrival, to proceed home a single ship. Macartney would later claim that he had delayed the Grosvenor in order to provide her with a naval escort. However, it was an explanation he never saw fit to give to Coxon, who could be forgiven for concluding that the Governor had kept him out of spite. Determined that his treatment would not go without response, Coxon presented himself that same day before Stephen Popham, a notary public, and issued a sworn statement, relating his trials at the hands of Macartney, deploring the ‘great risque’ to his ship and cargo caused by his departure so late in the season and ‘in justification of himself . . . protesting against the said Right Hon’ble the President and Council of Fort St George for having delayed him’.

So it was that, with barely a day’s notice, Coxon’s passengers mustered on the beach to be rowed out to the Grosvenor, joining the two already on board, Taylor and Williams. The most striking thing about them was the number of uniforms on display, not just maritime but army, French as well as British. They came, borne by palanquins and carriages, to the shingle beach where journeys to and from Madras invariably ended and began. Lesser figures came on foot, perhaps with a wallah holding an umbrella to shield them from the sun. The winds carrying the monsoon rain had blown themselves out and the light on a clear blue sea must have dazzled the eyes. At the water’s edge, teams of Tamil oarsmen, stripped to the waist, stood by their massoolahs, surfboats made of wood and coir, for the hair-raising dash through the breakers out to where the Grosvenor lay in that shimmering sea. Solid and proud, she suffered nothing by comparison with the men-of-war, frigates and ships of the line, of the Royal Navy squadron commanded by Admiral Sir Edward Hughes, which was massed some distance off.

The senior Army officer among the Grosvenor’s passengers was Colonel Edward James of the Madras Artillery, accompanied by his wife Sophia. The couple were probably in their mid-forties, having wed in 1763 when James was still a captain. He had left no glittering mark on the events of his time, but had been a witness to both triumph and disaster. He was probably at the capture of the French garrison at Pondicherry in 1761. He had been among the officers led a merry dance by Hyder Ali and, having risen to command the Madras Artillery, he had doubtless been at the Pollilur debacle, which saw the virtual annihilation of the Madras Army, including the deaths of sixty out of eighty-six British officers and more than 2,000 men. That catastrophe had caused not a few hearts to quail and, while there is no evidence that Colonel James had lost his nerve, he may well have thought it time to leave the field to younger men.

Of his wife Sophia we know only her maiden name, which was Crockett, and the fact that she was married at the garrison church of St Mary’s within Fort St George. The name Crockett was not uncommon in Madras, so the likelihood is that Sophia was the daughter of a local official or trader, rather than being one of that rather sad band of young women deemed unmarriageable at home and so sent to India to acquire a husband. The colonel’s servant was a soldier named William Ellis, while Sophia had an ayah.

A second officer of the demoralised Madras Artillery was also returning home. Of Captain Walterhouse Adair, however, nothing at all is known.

In contrast to these redcoats, we are on firmer ground with the two men in blue army uniforms. Colonel Charles d’Espinette and Captain Jean de L’Isle were prisoners, French officers of the Pondicherry regiment who had been assigned to help Hyder harass the British. Colonel d’Espinette was aged fifty-four, Captain de L’Isle – a short, ruddy man – twenty-seven. The details of their capture are not known, but they were being repatriated in a prisoner exchange. As officers they were treated as gentlemen – d’Espinette retained his servant, a man named Rousseau – although obliged to share a cabin with one another.

Five more British soldiers were returning home after their discharge, one of whom is of special interest to the Grosvenor story. John Bryan, aged in his thirties, had served in the Madras Army for about ten years. Such a career lent him an automatic distinction, for if there were few more desperate services for a poor young Englishman to enter than the Company’s forces, there had been no more deadly theatre of operations for British soldiery in recent times than Mysore. Bryan had survived a brutal disciplinary regime, tropical disease and the Pollilur disaster, in which hundreds of his comrades had died and thousands more been taken captive and forced to defect. He was, in short, a remarkably lucky man, a resourceful one, or both. Having escaped India, he was heading home with a shrewd instinct for danger, a small amount of capital, and practical smithing skills acquired in the Army. As troopers, Bryan and his four fellows would have messed with the sailors on the gun deck.

Among the other passengers we should take note of the half-dozen youngsters, and in particular one Thomas Law. Aged about seven at the start of the voyage, Thomas was identified by the sailors as ‘a young gentleman’ and ‘the son of a gentleman of quality who was very rich’. What makes this opinion additionally interesting in our race-obsessed age is that no mention was made of the fact that Thomas was Anglo-Indian. His father, also Thomas, was indeed ‘a gentleman of quality’, the son of a Bishop of Carlisle, who had arrived in Bengal as a clerk at the age of fourteen and formed a relationship with an Indian woman. He was barely sixteen when she gave birth to their son. Young Master Law, as he was called by the sailors, was being sent home with a servant to school.

Robert Saunders was also the son of a Company official and aged about six. Having no servant, he was travelling in the care of Captain Coxon. The two young female passengers, Mary Wilmot and Eleanor Dennis, were aged seven and three. They too were on their way to be educated in England.

As they came on board, the officers and crew surely cast a speculative eye from the quarterdeck and rigging over those for whose welfare they were about to become responsible. They would have expected to spend the next six to eight months, depending on the ease of the passage, in close proximity to these strangers.

That evening, as the passengers took their first meal together in the cuddy, the main topic of conversation was the unknown fate of the Grosvenor’s most distinguished couple and their alluringly empty cabin. In his four years as a captain, Coxon had never carried so prominent a personage as the Resident of Murshidabad, but his regret at losing the cachet that the Hoseas would have brought to his table, as well as the outstanding half of their £2,000 passage money, may have been tempered by the opportunity of auctioning the cabin space among the other well-heeled passengers.

The news arrived soon after dinner, as the passengers were about to take a turn on the quarterdeck: a country ship named the Yarmouth, carrying William Hosea and his entourage, had just dropped anchor in Madras Roads.

Hosea had given up hope a number of times. With the north-east monsoon behind them the journey to Madras would have taken a few days. Instead, the Yarmouth had been labouring for more than a month against the countervailing south-west monsoon, following a course that described a wide arc out into the Bay of Bengal and approached Madras from the south. Captain Richardson made the best use he could of the currents, but Hosea had thought the prospect of arriving before the Grosvenor sailed all but gone.

In the last week of March, six weeks after leaving Calcutta, the Yarmouth’s lookout had sighted land and the following day they had arrived at Pondicherry, where a French frigate and two smaller vessels lay at anchor. Although no more than the skipper of a country ship, Richardson was turned into a fire-eater by the sight of an enemy. Mary Hosea, the children and another woman passenger, were sent down to the ship’s magazine, a hell-hole where the temperature was well over 120°F, while the Yarmouth ran alongside the frigate, forcing her to strike her colours, then set fire to her. The British crew cheered while a thousand Frenchmen could only look on vainly from the shore.

Mary was still almost prostrate with exhaustion and fear from her ordeal in the magazine when the Yarmouth slipped into Madras Roads at about 8 p.m. on 29 March. Their joy at finding the Grosvenor still at anchor was soon alloyed by news that she was about to sail with the Royal Navy. Two hours later, Coxon came on board and, after confirming that he was under orders to join the fleet, gave them advice that was bizarrely misleading. As Hosea related it to Sir Robert Chambers in his final letter, Coxon told him that his cabin was ready and that ‘he had resisted many solicitations’ from others seeking its comforts. He then went on to say that ‘there were doubts of the fleet sailing in the morning’.

Reassured that he had a day or so to transfer his party and their mountains of baggage to the Grosvenor, Hosea sent Mary to bed, ordered transport boats to come to the Yarmouth at daybreak, and issued instructions that he was to be awakened at 4 a.m. He then lay down to get a few hours’ sleep himself. Barely had he put his head down than the officer of the watch roused him, at 2 a.m., and told him that the fleet was under way.

The Yarmouth’s crew threw themselves into the task of bringing up the trunks and furniture and loading the ship’s boat to be rowed across to the Grosvenor with Hosea. Having deposited one load, he returned with the Indiaman’s boat for another. Already, however, ‘the fleet was at a considerable distance, and I thought it best to despatch Mrs H and the children under the care of Richardson in his boat, desiring him to send it back instantly. My poor Girl was by this time so ill that she went into the boat more dead than alive.’

Even as the two boats started back for the Grosvenor, however, Hosea realised that distance was rapidly opening up between the Yarmouth and the fleet and if he waited for the rowing boats to return, he would never catch up. A native masoolah was summoned and loaded ‘with everything that I could perceive of most consequence’. Hosea was about to be subjected to the standard trick in trade of the Madras boatmen, an edge-of-the-seat process of bargaining and renegotiation as the craft tossed around in the sea:

I gave them money and promised large rewards. They put off and imagine my mortification when I found myself obliged to return, the boat being [so] overloaded that they refused to go without I would lighten her. I scarcely knew what to sacrifice & when it was finished it was broad day & the fleet four leagues from the land & every moment lessening to my view.

On the Grosvenor, meanwhile, Mary, seeing the land falling towards the horizon, became convinced that her husband was being left behind. She assailed Coxon – ‘she raved, she entreated, she threaten’d’. Coxon shortened the Grosvenor’s sails to slow her speed, only to receive a signal from Admiral Hughes ordering him to catch up.

So valiantly did the musoolah rowers exert themselves that Hosea had reached a rear ship, the Rodney. ‘Giddy, stupid, almost insensible of everything that had happened,’ as he put it, he was taken to the captain’s bed while the ship crowded sail to catch the Grosvenor. Mary was inconsolable, now certain that Hosea had been abandoned, until . . .

I reached the Grosvenor about eleven & flew to the best of women who, overcome by the variety of conflicting passions, fainted in my arms.

While it took Mary a few days to recover from this traumatic episode, Hosea’s sense of relief was palpable. His spirits were not even dampened by discovery that among their possessions left on the Yarmouth were the foodstuffs they had brought to relieve the dull fare of an Indiaman table, including their own livestock and wines. His books – ‘a choice collection for the voyage’ – had sadly also been lost, along with all young Tom Chambers’s clothing. Still Hosea’s mood remained buoyant. Their fellow passengers on the Grosvenor seemed as congenial a group as might have been hoped for: he mentioned in particular Colonel and Mrs James and the nabobs Williams and Taylor. Lydia Logie, the new wife of the chief mate, was ‘the finest lady’. He had reassuring news too about the Chambers’s son: ‘There are a great number of children in the ship & Tom is very happy & a great favourite with everybody. He has a most excellent Temper & is very easily managed.’

Well might Hosea have reflected that the upheaval had been worth it in the end. All the anxieties of Bengal were behind them and they were bound for England, home and comfort. The teenage boy who had left seventeen years earlier with nothing was returning, a man of substance and family, in pomp.