THE CALIBAN SHORE

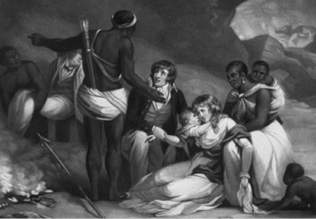

African Hospitality, detail of engraving by John Smith, 1791 from the painting by George Morland

Lambasi, Pondoland, 4–5 August 1782

Among the paintings inspired by the Grosvenor story is an oil by the English artist George Morland entitled African Hospitality. A florid piece of Enlightenment romanticism, it depicts the immediate aftermath of the wreck. The distressed Hosea family are at the centre of the tableau, against the backdrop of a lightning-pierced sky and the dying Indiaman. William, dishevelled and apprehensive, kneels supplicant-like before a half-naked warrior. Mary, all ringlets and disarrayed muslin gown, clutches baby Frances while reclining exhausted in the arms of a black Mother Earth figure. The warrior’s burly physique and weapons – a spear and an anachronistic quiver of arrows – assert his dominance, but his open hands, gesturing to a shelter, offer no threat, only compassion. The sturdy matriarch, surrounded by infants, meanwhile shows by her embrace a readiness to enfold these new babes. Elsewhere, Africans are carrying sailors ashore, succouring them with food and drink. The tempest from which they have emerged is contrasted with the idyll to which it has brought them. All will be well for the castaways, the image says; they have fallen among noble savages.

Morland was the most gifted English artist of his day, a prodigy held to be the natural successor to Reynolds and Gainsborough, and the painting, from 1790, captures the moment in which a crusade was born. Reckless, dissolute, a drunkard, and frequently in debtors’ prison, Morland had made his name with sentimentalised scenes of rustic English life before being recruited by the embryonic Emancipation movement to produce African Hospitality and its companion piece, The Slave Trade, a scene of white seamen brutalising an African family. The artist’s challenge to contemporary wisdom – the paradoxical representation of beastliness in Europeans and humanity among Africans – was brave and visionary, and the success of African Hospitality, exhibited at the Society of Artists, may have surprised Morland himself. He cannot be blamed for the doggerel that appears beneath an early edition of the mezzotint reproduction:

Dauntless they plunge amidst the vengeful waves

And snatch from death the lovely sinking fair.

Their friendly efforts, lo! Each Briton saves!

Perhaps their future tyrant now they spare.

The picture retains a sense of wonderment, capturing as it does the instant in which two alien cultures met, and contrasting to startling effect the helplessness of the white gentlefolk, tossed up like Shakespeare’s mariners in The Tempest on an inaccessible shore, with the self-assurance of the semi-naked blacks. And if the overall effect is somewhat cloying, it is still an intriguing counterpoint to the subsequent Victorian portrayal of Africans as wide-eyed berserkers, the heathen foes of Empire. All the same, it is hard to look at African Hospitality without wondering how Morland came by his concept of these events, and what the castaways would have made of it.

With black sea pounding around them that first evening, passengers and crew sprawled in loose-knit groups at the water’s edge. It was just twelve hours and a lifetime since the first juddering impact. They were drenched and cold, and most were too exhausted to move, too stunned by the enormity of what had befallen them to take it in. Some wandered about, disorientated or distracted. Others lay, seemingly lifeless or clutching injuries from their battering in the water. But few could take their eyes from the scene before them.

Half-naked figures flitted amid the flames of half a dozen fires flickering along the rocks. The apparitions went about their work with silent intensity, absorbed by a single task. Heedless of the aliens tossed up in their midst, they were feeding wooden wreckage into the flames in order to extract the metal fittings. They were dark, almost black in complexion. One sailor noted, ‘They went quite naked except a slight covering round the loins,’ although another saw that in addition, some men wore cloaks made of cattle hide which hung from shoulder to knee. ‘Robust and well proportioned’, they wore their hair piled on their heads in hollowed cones. One of them, coming upon a sea chest, smashed it to pieces to extract the brass nails, which he stuck into his hair as ornaments.

To some of the Europeans’ treasures they were entirely indifferent. While the nabobs’ bales of silk drifted in on the tide, the natives paused merely to cut open one or two with assegais and inspect the contents before returning to the fires. More wood was tossed on to the flames and, as each piece was consumed, an iron ring here or a few steel bolts there were extracted from the embers, dipped hissing into a pool, and added to a growing pile of metal oddments.

For an hour or so after the last of the survivors came safely ashore, the two groups remained in this state of utterly disconnected proximity. Then, quite suddenly as the light faded, the tribesmen gathered up their booty and, without a backward glance, disappeared over a grassy ridge into the darkening hinterland.

Among the seamen, initial relief that the cloaked warriors evidently intended them no harm was soon replaced by a sense of bewilderment. There was something unnerving about the systematic way the men had gone about stripping metal from wreckage, almost a familiarity with the process, like carrion-eaters knowing how to get at the choicest bits of a giant carcass. Then there was the curious indifference of the natives to their plight. The seaman William Habberley, for one, found it unsettling . . .

. . . our dreadful situation not apparently affecting them, as they never offered us any assistance.

Now, though, in the gathering gloom, the castaways were alone with the snap of the fires and the crash of the sea. Where the tide swirled around an inlet, the Grosvenor’s forecastle and stern reared high and black against the dying light, a grotesque spectre of the grand Indiaman. This sight of what had been their home for these past months brought home a renewed sense of shock and loss.

Gradually the seamen were roused to action by some of the objects washed up. Geese and chickens lay lifeless in sodden heaps on the rocks. A few creatures from the ship’s menagerie had escaped alive, including some pigs, which could be heard grunting at the sea’s edge. A sudden hunger awoke, for no one had eaten that day. Fires were stoked and, while women and children gathered around for warmth, the men collected the dead fowl and roasted them. Just twenty-four hours earlier, diners in the cuddy had been replete with supper and madeira, and men in the mess jolly with grog and song, drinking to absent friends. But that night, 4 August, after months together at sea, they ate as a company for the first time.

Convention was restored after the meal. The seamen moved a short distance off, leaving the passengers and officers to a kind of privacy. Soon afterwards it began to rain and they were reunited in a common state of damp misery, broken by the cries of the injured and the mutterings of those in the grip of a waking nightmare. All through the night men and women dozed off and awoke, feeling at first a vague unease but also half-expecting to feel the familiar rocking of the ship. Their systems habituated to the motion, some actually felt themselves to be still at sea, and in their semi-conscious state had a moment of relief as the wreck became, briefly, just a terrible dream. Then they came fully awake, to find with sickening terror that they were, indeed, cast away in Africa.

Dawn came up on the morning of 5 August on a world turned upside down. Like any ship’s company, those on board the Grosvenor had sailed with an apprehension of danger. What they had feared was shipwreck and death. Shipwreck and survival was not a possibility that anyone had much considered. In the event, the great majority had survived. Seamen and passengers had, of course, escaped shipwrecks together before; but never had a company from so broad a spectrum of British society found itself so distant from the old certainties, or so ignorant of the shore on which they were lost.

Some of the demons of the night, at least, had disappeared. The spectral figures were nowhere to be seen and the men were able to study at leisure the shore on which they had foundered. In her death throes, the Grosvenor had been drawn into an inlet composed of a low shelf of flat rock that narrowed from a width of about fifty yards and rose in tiers to a grassy ridge. What was described by some of the men as a ‘steep, almost perpendicular’ cliff and represented as such in paintings of the wreck was, in fact, a tier of rock on the south side of the inlet rising to a height of about 30 feet above sea level. The south-west wind that had brought them to grief churned up the sea boiling around the inlet and, as the Indiaman was smashed to smaller and smaller pieces, those watching from the shore had cause to reflect again on their astonishing escape.

Venturing up on to the ridge during the morning, the men found it barren of trees or any other sign of life as it rose gently inland. The coastline that stretched away on either side was rocky but also seemingly devoid of significant features. On closer inspection, however, a bay to the south of the inlet concealed a large tidal pool separated from the sea by a wide sandbar. The bay, known as Lambasi by the natives from time immemorial, was about a mile broad, with the pool at its centre. But for their circumstances, the place might have struck the men with its loveliness. Surrounded by beach, forest and rock faces, the pool was fed by a stream and a river, the Tezani, which came down from a distant ridge of hills and threaded its way through a valley surrounded by sheer walls of black sandstone to a height of about 80 feet, sprouting wild banana and flowering protea trees. The scene was a microcosm of what lay beyond: a gentle green pastoral, a scene to gladden any eye, concealing something altogether more primordial.

A semblance of shipboard discipline was re-established. Shaw and Beale mustered the men for roll-call, and an inventory was taken of the fifteen dead. Along with Captain Talbot’s lad, they included nine foremastmen, John Woodward, the quartermaster, William Milbourn, a midshipman, Simon Griffiths, bosun’s mate, and Christopher Shear, poulterer. Among the injured was Coxon’s servant, Robert Price, still insensible after being dashed against the rocks. Many others had gashes and fractures. Logie, the chief mate, roused from his sickbed during the wreck, had lapsed again into feverish unconsciousness. With neither instruments nor remedies, there was little that the surgeon Nixon could do for any of them.

There were 125 castaways in all. The ninety-one seamen included the captain and five officers, eight servants, twenty petty officers and artisans, thirty foremastmen and twenty-five lascars. Among the thirty-four passengers, eighteen fell into the category of gentry, eleven were servants and five discharged soldiers.

We get glimpses of them that first morning. Despite the panic of the wreck there had been enough time to dress and collect a few valued possessions, and Charles Newman had on the green broadcloth coat with silver monogrammed buttons that he had used to wear to the Bengal Supreme Court. In the gold-braided jackets of a colonel and a Navy captain respectively, Edward James and George Talbot cut equally incongruous figures in these new surroundings. The traders George Taylor and John Williams, as well as donning their breeches and coats, had managed to scoop up a number of valuables, gold chains and watches; these offered little comfort as they looked down on the bay from a grassy ridge to see the silk bales that represented their fortunes, the product of years of endeavour, drifting limply at the sea’s edge like jellyfish.

Lydia Logie, her mane of red hair hanging dishevelled around her shoulders, wearing the gown she had slipped into after the ship had struck, watched over her sick husband. Married just eight months, now visibly pregnant, Lydia had ventured around the world to meet her mate, only to have the prize of their new life snatched away. Logie, the strong, reassuring figure of the Grosvenor’s quarterdeck, appeared now shockingly vulnerable, bathed in the sweats of dysentery, the seamen’s ‘bloody flux’.

A few yards off, William and Mary Hosea clung to each other and their child Frances. Hosea had with him his valuable package of diamonds, so not everything had been lost; but the couple had been reduced to a pitiful state. As we have seen, Mary’s letters are suggestive not of a doughty memsahib but rather a sweet, considerate woman, inclined to fret about her family and her health. From the outset, she had been full of worries about the voyage. On the eve of their departure her friend Eliza Fay wrote: ‘Her anxiety [is] great.’ Mary had died of fear more than once during the previous twenty-four hours and, having spent a night out in the open, was now shivering in her still-damp gown, trying to comprehend what sort of a place it was that they had come to. Utterly traumatised by the succession of disasters that had befallen them, she must have felt they had become the playthings of a malevolent spirit. Hosea himself, agonising at the recollection of how close they had come to missing their passage on the Grosvenor, was additionally burdened by the fact that they had succeeded only because of his obstinate determination to be quit of India.

Their fate now rested in the hands of one man. John Coxon, however, had problems of his own. His ship and his cargo were lost; it was his negligence that had helped to bring them to this place; and his most trusted and able officer was sick and possibly dying. Coxon’s record offered little to encourage a belief that he was the man to guide his charges to safety, and from the outset he seems to have been overwhelmed by that responsibility.

When a troublesome seaman was purposely marooned, he was not left without resources. Alexander Selkirk, history’s best-known castaway, was landed on Juan Fernandez island in 1704 with a pistol, gunpowder, a hatchet, a knife, some provisions, a pot in which to boil them, a Bible, bedding, navigational instruments and charts. He survived for four years and four months before being rescued. Another seaman, accused of sodomy and abandoned on Ascension in 1721, had in addition a fowling piece, a tent, buckets and a water cask. He fared less well and was found some years later, a skeleton beside a diary that petered out in mid-prayer. Thanks partly to the circumstances of the wreck, but also to events in the immediate aftermath, the Grosvenor castaways were not nearly so well endowed.

The crew spent the morning of 5 August foraging at the water’s edge. Debris was strewn among the rocks and a wave of flotsam bobbed in on the tide. Shoes were quickly collected, for many of the men had lost theirs in the wreck; but according to Dalrymple’s report there were many other useful objects as well:

Plenty of timber from the wreck and the booms and sails were cast ashore, sufficient to have built and fitted several vessels; nor were tools, as adzes, &c. wanting.

Two sails were recovered, including the mizzen topsail still attached to the yardarm. They were carried the few hundred yards down to the tidal pool, where the stream provided fresh water for drinking and bathing, and rigged as tents, one for the women and children, the other for food and essentials. The men set up their own camp further upstream. Drenched bales were broken out and soon the grassy verge was festooned with tents of bright silk.

Meanwhile Habberley and another group of men found: ‘A pipe of wine, a barrel of arrack and a cask of flour with a tub of beef and pork, which were all carefully conveyed to the tent and taken care of under the captain’s directions.’

If their immediate needs were met, their situation was nonetheless dire. They were lost on a shore known to none, halfway between England and India, and hundreds of miles – quite how many would be a matter of much conjecture – from the nearest European settlement, without charts or navigational aids. Coxon knew that the Portuguese were at Delagoa Bay to the north and the Dutch at the Cape to the south, but the two were separated by well over a thousand miles and he was far from clear about his position in relation to either. Rescue by another ship had to be discounted, as no vessels landed between these ports except in emergency. That left two possibilities for deliverance. The most straightforward was an overland march to the nearest Portuguese or Dutch outpost. The second was to deploy the skills of the artisan crew – carpenters, caulkers and coopers – to build another vessel. Although a challenging task, it would not be the first time this had been done by seafarers wrecked in southern Africa.*

In any assessment of their plight, one factor stood out: the castaways were quite without firepower. In their haste to abandon ship, Coxon and the officers had failed to ensure the salvage of either charge or ball; the Grosvenor’s entire load of gunpowder was at the bottom of the sea. Their pistols and muskets might as well have been there too. Whether for defence against human or animal assailants, or for hunting, the firearms were useless.

They were not long in being confronted with their vulnerability. That same morning the natives returned.

The official inquiry into the Grosvenor disaster, commissioned by the directors of the East India Company, was conducted by Alexander Dalrymple, the Company’s hydrographer and the man responsible for its seafaring operations. His findings, published in August 1783 and based on his interrogation of survivors, are brief and dispassionate. One sentence, however, stands out for its pithy eloquence:

In great part, their calamities seem to have arisen from want of management with the natives.

Dalrymple was no deskbound bureaucrat. In his youth, he served the Company as a minor official in Madras in the 1750s before sailing to the Malay peninsula and discovering a passion for cartography and navigation. From 1762 he made a series of voyages to the Indonesian archipelago and China, and ten years later published accounts of his travels. However, it was his interest in the great geographical issues of the South Pacific that made his reputation and saw his elevation to the position of hydrographer. A disputatious and cantankerous Scot, Dalrymple was a figure formidable enough to have crossed swords with the hero of the age, the navigator James Cook, over the existence of Terra Australis Incognita, the Great Southern Continent.* When he sat down to take evidence from the Grosvenor survivors at the Company’s Leadenhall Street headquarters in the summer of 1783, he had Cook’s fate clearly in mind.

Cook’s voyages between 1768 and 1780 established him as an explorer in the heroic tradition of Da Gama and Magellan. Not only did he add immeasurably to geographical and maritime knowledge, but he brought home the image of an enchanted world – of sun-kissed Pacific archipelagos, lovely in aspect, abundant in the fruits of nature and, above all, lavish in hospitality. Cook had seemed to establish an understanding with the islanders, seeing them as noble in their nakedness and simplicity, and winning their trust. One of his protégés, a Society Islander named Omai, was lionised in London, being taught etiquette by Joseph Banks, introduced to King George, painted by Reynolds and generally made a fuss of. Between Cook and his French contemporary, Louis de Bougainville, who was captivated by Tahiti, the fashionable salons of London and Paris were flushed with enthusiasm for the philosophy of Rousseau and the purity of the noble savage.*

Then, in January 1780, Britain was stunned by news that Cook was dead, stabbed and beaten to death in a skirmish with his beloved Pacific islanders. The London Gazette reported that the cause of this affray ‘with a numerous and tumultuous Body of the Natives’ was their thievish activities. There were dark hints of cannibalism.

The murder of the great mariner made a profound impression on its time. To a nation invested with a growing sense of its own righteousness and power, it seemed that Cook’s reward for trusting and befriending the natives had been treachery: in the end, it turned out, the noble savage was just a savage after all.

If the islanders of far-flung archipelagos were seen by the English public as brutes, another race occupied an even lower place in the scales of humanity: the dark, semi-naked inhabitants of Africa. Partly this was based on ignorance. Of the region south of the Sahara little more was known than had been postulated by Ptolemy 1,600 years earlier in a map showing the Nile taking its rise in two great lakes watered by the Lunae Montes, the Mountains of the Moon; even now maps of the African interior were embroidered with fantastical creatures and freakish humans, and when, in 1790, James Bruce published an account of his journey to the source of the Blue Nile, he was dismissed as a fantasist. However, a second factor underpinned a common belief that the natives of Africa were not quite human.

The British slave trade started on a small scale in the 1560s. Opinions of the coastal people of West Africa were never high. ‘The Negroes [are] a people of beastly living, without a God, lawe, religion, or common wealth,’ wrote an early English visitor. But as the trade gathered pace, it fed yet darker perceptions of Africans. By the late eighteenth century, Edward Long, a historian, could describe Africa as ‘that parent of everything that is monstrous in nature’, and its inhabitants as ‘libidinous and shameless as monkies’. Visitors to the kingdom of Dahomey vied with one another in depicting the savagery of the regime. One, Archibald Dalzel, wrote of the king’s palace ornamented with human heads and bestrewn with bodies, and went so far as to claim that removing poor wretches from these circumstances to the plantations of Jamaica and Virginia was an act of compassion. By the time of the Grosvenor’s last voyage, more than two million West Africans, an annual average of 20,095, had suffered the questionable mercy of the Atlantic slavers. That same year one of the most notorious episodes in the history of the trade occurred: Luke Collingwood, captain of the Liverpool ship Zong, cast into the sea 131 ailing slaves whom he suspected might not survive the voyage to Jamaica, in order to collect the insurance.

Intellectuals – writers in particular – contested the notion of a beastly savage with an equally ethnocentric if more benign alternative. While George Morland depicted Africans as noble on canvas, William Blake and Robert Burns did so in words, the latter in verse, penned in Scotland, celebrating a supposedly idyllic life ‘in sweet Senegal’. Of how Africans actually lived or thought there was little knowledge and even less understanding; but often there was sympathy. Samuel Johnson’s friend Hester Thrale thought interracial mixing was ‘preparing us for the moment when we shall be made one fold under one Shepherd’. Daniel Defoe, one of the earliest opponents of slavery, may be said to have created the literary prototype for the noble savage in the form of Crusoe’s Man Friday, while Johnson challenged the slave trade in typically ebullient fashion, startling the men of Oxford with a toast, ‘To the next insurrection of the Negroes in the West Indies.’*

It would be facile to claim that the racial debate going on among European polemicists had any effect on the crew of the Grosvenor. Among ordinary seamen the issues of class and hierarchy were more relevant, and the survivors’ accounts of the people they encountered are marked by bewilderment rather than hostility. Nor is there any information to suggest that Captain Coxon shared the view of another Indiaman captain who wrote of the natives at the Cape of Good Hope that ‘of all people they are the most bestial and sordid. They are the very reverse of human kind . . . as squalid in their bodies as they are mean and degenerate in their understandings.’ But attitudes among some of the castaways, a dread of this shore and its inhabitants, undoubtedly had a bearing on what passed after the wreck. Dalrymple’s judgment that there was a ‘want of management with the natives’ was, if anything, an understatement.

In accounting for what followed it may also be relevant to note that the news of Captain Cook’s death had reached England just four months before the Grosvenor sailed for India. Coxon’s conduct after the wreck bears all the marks of one acting in the shadow of the illustrious mariner’s fate.

There was no immediate hint of trouble on the natives’ return. Indeed, the dark figures approached in a way that signalled peaceful intentions. This time they were accompanied by their womenfolk, who remained some distance off with the warriors’ spears and shields. As before, it was clear that their sole interest was metal from the wreck.

At first the seamen took the natives’ presence in their stride. There was at least one amicable exchange. Two men, John Warmington and Barney Leary, related that when the tribesmen came among them, they ‘pointed [to the north-east] and said something, which they imagined was to tell them there was a bay that way’. The natives were gesturing towards Delagoa Bay, and indicating that yonder the castaways could expect help from others of their own tribe.

While struck by the novelty of the natives’ appearance – ‘woolly-headed and quite black’, noted another foremastman, John Hynes, who had never left his Irish homeland before the start of the voyage – the sailors were initially content enough to let them share in the bounty of the wreck. It was not long, however, before scavenging became more like high-handedness. ‘They seemed to consider everything as belonging to them,’ Habberley complained.

More important than the attitude of the seamen was the alarm and dread that the natives’ return had excited among the passengers. Hynes noted that when the blacks ‘began to carry off whatever seemed to strike their fancy’, it

excited in the minds of our people, particularly the women, a thousand apprehensions for their personal safety.

It is not hard to identify those most likely to have been affected. Nothing in Mary Hosea’s life had prepared her for these horrors. She may have travelled across the world, but as a Calcutta lady her experience of dark peoples was limited to ayahs, chowkidars, kitmugars, jemadars, and other servant wallahs. Living in India may even have made her more disposed to anxiety, for it inculcated a conviction that the forces at work beyond Company settlements needed to be kept at bay. Her resources were now exhausted.

To Mary’s condition was added her husband’s attitude to people of dark race. William Hosea had little enough time for cultivated Bengali nobles, and none at all for the lowly of any other race. His response on being advised once that 200 sepoys – Indian troops in the Company’s service – were being cared for as invalids in Madras was chillingly redolent of the Zong’s captain. ‘This is certainly a very melancholy circumstance & might be easily remedied by throwing them all into the sea,’ he wrote. Highly strung and nervous, Hosea was not a man likely to behave rationally on finding himself at the mercy of those he saw as inferior.

At some point during the day, Coxon had talks in the makeshift canvas tent with his officers and the senior passengers, including Hosea. Whatever the nature of the discussions, they did nothing to resolve a delicate situation. After the miracle of their deliverance from the sea, a jarring pattern of events resumed.

It was clear that survival would depend on the passive cooperation, if not the direct assistance, of the local people. It was also obvious that the natives would seize on useful objects from the wreck, and that this foraging would have to be balanced against the castaways’ own needs. The ship’s company was quite formidable in number and certainly not defenceless, for although without guns they had at least half a dozen cutlasses. An opportunity existed for some firm-handed gesture of friendship, leading to barter. Africans had been trading food with seafarers for generations. Yet no attempt at communication was made at all. Instead, the situation was allowed to drift through the afternoon, to the point that the sailors felt they were without leadership, and the natives were given too broad a licence to plunder goods that were essential to the castaways themselves.

Coxon was understandably concerned about the possibility of trouble between the sailors and the natives, and had given orders that the men were not to offer any kind of resistance unless attacked. But while it was important to avoid provocation, it was vital to demonstrate that they were not afraid. In those critical early days, the captain adopted a tactic of ignoring the Africans entirely, evidently in the hope that they would simply go away. Whether he was persuaded of this approach by Hosea, whose opinions as the senior civilian had acquired a new influence now that they were back on land, or had decided on it himself, is not possible to say. It was, in any event, a terrible mistake.

One incident defined a pattern. Habberley was with a group of men scouring the rocks when they came upon copper saucepans and carpenter’s tools. These precious finds were being carried back to the camp when the seamen were surrounded by warriors

who endeavoured to wrest them from us, but being loath to part with such conveniences, we held them fast and would not suffer them to take the same. They then immediately had recourse to their arms and appeared determined to have them.

The confrontation was resolved by Shaw, who told the men to surrender the items. They obeyed reluctantly, Habberley related, ‘not out of any fear of the natives or their arms, but out of respect for Mr Shaw’. The incident signalled that the sailors were anxious to avoid confrontation. That impression might have been balanced by a subsequent demonstration of firmness, but it was not. Thereafter, Habberley wrote, they were obliged to conceal ‘everything we found made of metal . . . otherwise [the natives] would not let us have them’.

As well as trying to ignore the natives, Coxon seemed reluctant to engage with his own men, for no attempt was made to communicate with them either. Tension rose through the afternoon. In the absence of leadership, men were starting to ask who was in charge now that they were no longer at sea. Habberley noted: ‘Many sailors and lascars, thinking all command at an end, were beginning to be very disorderly.’

Some hands found a barrel of arrack and got drunk. By this time Habberley believed that there really was a danger that the unruly and increasingly frustrated men might provoke the natives and bring down an attack on them all. Only now did Coxon make an appearance, moving among the men with Shaw to calm them and ‘prevent tumults’.

The moment of danger passed and, as the sun went down, the natives again went off into the dark; but the sudden ugly turn of mood may have been seen as a portent. A few sailors were heard muttering about leaving. Lascars, too, were talking of striking out on their own; it could have been argued by the Indian sailors that they had a better chance of survival among another dark-skinned people than if they stayed with the Europeans.

One seaman caught the mood. Joshua Glover, a foremastman of unknown background and age, turned his back on his shipmates and, when the natives disappeared with their booty that evening, he went with them. The consensus among the company, according to Habberley, was that Glover was a loon, ‘disturbed in his mind’. Events were to show that he was nothing of the sort.

An uneasy quiet descended on the camp. A ration of arrack was distributed among the men, along with flour and portions of salt pork and beef. The flour they mixed with water to bake into cakes that were eaten with the cured meat. Afterwards the seamen were divided into watches, and at the end of that first full day in Africa, guards were set ‘to prevent the natives from plundering or sacrificing us’.