‘A SACRED CHARGE’

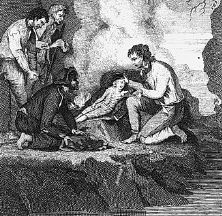

The Death of Master Law, copperplate by George Carter, 1791

The carpenter’s party: 22 August–29 November

Habberley had been unusual in allowing his pace to be dictated by his charges, but a still more noble exception to the instinct for self-preservation was to be found in the party led by Thomas Page, the carpenter. While Habberley had been shepherding Taylor and Williams, an epic of self-sacrifice was being enacted three or four days’ march ahead.

Charles Dickens thought the story of Thomas Law ‘the most beautiful and affecting I know associated with a shipwreck’. Alexander Dalrymple obviously had it in mind when he expressed satisfaction at finding ‘so many efforts of generosity and mutual assistance’ among the castaways. He heard about it from the survivors and his report gives an account of the little Anglo-Indian boy. However, the principal version of the story, and the one that made such an impression on Dickens, is contained in George Carter’s Narrative of the Loss of the Grosvenor.

Carter was a hack artist who, in 1785, took passage to try his hand in Bengal. The Grosvenor wreck remained fresh in the public mind and with information that he had gleaned on the voyage out, Carter painted at least two scenes from the drama. To judge from the only one that survives, The Shipwreck of the Grosvenor, a gouache in the vaults of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, it is no surprise that he is entirely forgotten as an artist. Competition was especially keen in Bengal, where the rewards for the successful in any field were spectacular; Zoffany, the society portraitist, and the uncle-and-nephew team of William and Thomas Daniell, in the field of topography, made fortunes as well as names for themselves. Carter meanwhile gave up after a few years and sailed back to London.

But Britain’s awakening curiosity in far-off lands, and the interest in seafaring dramas, shipwrecks and castaways – an appetite fed by the phenomenal and enduring success of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, published sixty-five years earlier – had given Carter an idea. In 1791 the firm of John Murray published his account of the Grosvenor. Readers were promised . . .

A Variety of Matters respecting the Sufferers,

Never before made Public:

With Copper Plates descriptive of the Catastrophe

engraved from mr carter’s designs

The Narrative was a huge success. From the time that news of the wreck reached England, public fascination with the Grosvenor had been matched only by the paucity of information about the subject. Dalrymple’s inquiry produced a taut document, sparing in detail and limited in circulation. Now here, after a silence of eight years, was the first widely available account of the disaster. Moreover, it turned out that Carter was a very much better story-teller than he was artist. He allowed his imagination to run free and he seized on the big moments. Biggest by far was the story of Tom Law.

The sailors could have had no illusions about what was involved when they decided to take a seven-year-old boy with them. As Habberley noted, Tom had required help from the outset, ‘being carried by the party and they in consequence being very much wearied’. When he was able to make his own way, the others had to slow their pace to his. At no stage is there mention of any objections to this, and while the steward Lillburne was Tom’s principal protector, others sacrificed themselves for the lad too. Thomas Lewis told the inquiry:

Master Law was first carried by William Thomson, midshipman, and then by each of the party by turns; and when they were knocked up, Mr Lillburne said he would save the boy’s life or lose his own.

The carpenter’s decision to stay by the sea was soon vindicated. While Shaw’s group were stumbling inland, the twenty-four men led by Page made comparatively good headway, although the strain of carrying the child was too much for Midshipman Thomson, who died early on. Two days after parting from the second mate they reached the mighty Umtata.* Carter’s narrative is short on details of how such obstacles were overcome, but Page’s party seem to have made better use of rafts than the others. After that the worst of the broken country was behind them and hopes rose. With the sand firm beneath their feet and the sun on their backs, they could cover up to fifteen miles in a day. They discovered simple new pleasures – bathing naked in a river, a bed in the warm, soft beach sand at the end of a day – along with exultation in the odd unexpected find, such as berries ripening in the sun. In the evening there was time for reminiscences of life before the wreck, for anticipation of debauches to come at some Thames inn – Lord, how fine a tankard of ale would taste! – and, perhaps sometimes, enough spirit left in the sailors for one of their songs.

Henry Lillburne’s background and age are not known. As steward, he had been in charge of the Grosvenor’s provisions and, endowed as he was with authority, the men looked to him for orders even though the carpenter was acknowledged as leader. Lillburne was a literate man, able to sign his name in the ship’s impress book, but not necessarily an educated one. He was strong enough to carry a child on his back across heavy ground, and we can imagine him as burly as well as gentle, epitomising the fondness found among some elder crewmen for youngsters. Ships’ boys were intrinsic to British seafaring and in our cynical age it is easy to see something unwholesome in this tradition. In a more innocent time, the old salt was almost synonymous with indulgence towards youth. For many men, such ties were the closest they would come to the father–son relationship of home life. In the case of Lillburne and Tom Law, the evidence points to an act of simple devotion, and the natural response of a child in a crisis to a strong, paternal figure.

A handful of other individuals also attract our attention. Francisco di Lasso, a native of Genoa, was another father-like figure. He had saved Robert Price, servant to Captain Coxon, when he was dashed on the rocks, pulling him from the sea by his hair, nursing the lad as he lay unconscious for almost two days, and keeping an eye on him when the march began. Price, now aged about fourteen, had opted at the parting to follow his guardian rather than his master and, having recovered fully, was repaying Di Lasso and his shipmates with his abilities as a forager and diviner of drinking water. Price’s closest friend was another youngster who had been in Coxon’s entourage: his steward William Couch.

Jeremiah Evans, born amid the lanes of Wapping, was aged eighteen, a wiry hand whose experience clambering up rigging had served him well in tackling the sandstone heights and forests on those desperate days early in the march. Barney Leary was a bullock of a youth, with ‘a very robust habit of body’. He had started the voyage as the only sailor with the novice rating of landsman, indicating that he too was still in his teens. Even so, these young men regulated their pace to the child – and were duly caught up by some of the sailors from whom they had separated about a week earlier.

It may be recalled that Shaw’s company had been left at the Umtata by two groups of men able to swim. The first included Hynes and Warmington, the second Lewis. These men, ten in all, were soon reunited and caught up with Page towards the end of August. For a couple of days the party was increased to thirty-four, before the pattern of disintegration resumed. Carter, trying to make sense of the random break-ups, interjected exasperatedly into his narrative: ‘I cannot help lamenting that persons in so perilous a situation as these poor shipwrecked wanderers, should be wanting in that unanimity which alone would ensure their preservation.’

In the 140 miles or so that lay between the Bashee and Great Fish Rivers, bands of men appear to have been breaking up and reforming almost daily. By the beginning of September, Page’s party had splintered into at least half a dozen bands. What acts of heroism and betrayal went unrecorded will never be known. We are left with a pattern of human behaviour in crisis. A group would fragment as a few sailors, almost invariably the younger, found that they had to moderate their pace to allow the others to keep up, and gradually would forge ahead. This winnowing of the weaker men was so undramatic, a slow widening of space between two groups, that it might not have occurred to anyone that they had actually been abandoned until their fellows were, quite suddenly, out of sight.

To follow each group is not possible, and on the basis of the limited evidence available would not add to the overall picture. Percival Kirby, who studied the Grosvenor sources minutely, commented wryly: ‘The evidence of the survivors at this stage of the journey is so conflicting that one can hardly say more than that the whole of the coastline from the Bashee southwards must have been dotted with small parties of men, separated from each other by several miles, and making their way slowly in the direction of Algoa Bay while struggling desperately to find sufficient food to keep body and soul together.’

We are on safer ground in following what became of a core group that stayed with the carpenter. Within a few days of crossing the Bashee they had been reduced from thirty-four to twenty, including Page himself, Lillburne, Di Lasso, Price, Couch, Evans, Leary and Tom Law out of the party that had separated from Shaw in the first instance, and Hynes and Warmington from those who had left the second mate’s company at the Umtata.

A month after the wreck, they had entered the Xhosa country and were ‘passing many villages without being molested’ while still finding little willingness among the inhabitants to part with food unless it was for barter. Jealous of their livestock, the tribesmen were also in no position to make free with the remains of the previous harvest when it would be at least another two months before new crops were available. Dalrymple, with the benefit of both hindsight and objectivity, went some of the way to understanding their wariness. The natives, he wrote,

treated the individuals that fell singly among them rather with kindness than brutality, although it was natural to expect that so large a body of Europeans would raise apprehensions; and fear always produces hostility.

By now it seems that the seamen were themselves so suspicious that they did not always respond even when friendship was offered. They were among the Gcaleka Xhosa, a people who – unlike the Rarabe Xhosa, who had killed Taylor and Williams – had no record of conflict with whites. A band of young men approached Price with his friend William Couch on the beach one day, and offered him a spear. As Price himself recognised, this gesture was ‘by way of making friends’; they took him by the arm, indicating that they wished him to accompany them. Price, however, was so traumatised that he began to weep. Couch and the others started crying too, whereupon the unnerved Xhosa retreated.

The Irishman Hynes was more perceptive than most in realising that behind what seemed to be the natives’ indifference to the castaways’ plight lay a real fear for their most treasured possession, their livestock. Noting how even in this fine cattle country, the Gcaleka ‘would neither bestow any, nor suffer [us] to purchase any by way of barter’, he related: ‘So apprehensive were the natives of the strangers stealing their livestock, that they constantly drove them away as they approached the Kraals.’* But although the Xhosa refused to feed so large a party, Hynes also noticed how Tom Law would be singled out by women when they came to a village and given milk ‘contained in a small basket, curiously formed of rushes, and so compact as to hold any liquid’.

The discovery of a dead whale provided another occasion on which the Xhosa demonstrated goodwill. The castaways’ joy at the find turned to apprehension as they saw a large party of men approaching with assegais. ‘The natives, however, no sooner saw in what a deplorable situation they were, and how unable to make any opposition, than they conducted themselves in so pacific a manner as to dispel their fears. One of them even lent those who were employed on the whale his lance to cut it.’

After almost two months on a diet of molluscs and water, their greatest enemy had become malnutrition. At just what point it did for Page is not known, for Hynes became detached from his party, and when he rejoined them some days later it was to find that the carpenter was dead. He had been buried in the sand near the Keiskamma River towards the end of October. At this point his group had covered almost 250 miles, were within half that distance of refuge and were on the easiest terrain they had yet found. Now under the leadership of Lillburne, they stepped forth each day on clear sand that curved away into the distance. Yet two daunting obstacles still lay in their way: a river and a desert.

The Great Fish River was reached within a few days of Page’s death. Yet again in the face of crisis the men fell out, or in any event fell apart. The nineteen-strong company split into three. Five men stayed behind to die, including Isaac Blair, the servant whom Captain Talbot had urged to carry on. Two groups of seven crossed separately on rafts. The first included Di Lasso, Price, Couch and Leary. Among the second were Lillburne, Evans, Warmington, Hynes and Tom Law.

Tom, according to Hynes, had ‘borne the inconveniences of so long a journey in a most miraculous manner’. For weeks he had pattered along beside the men, although there were still places where he had to be helped: ‘When they came to deep sands, or passed through high grass, which was often the case, the people carried him by turns.’

Lillburne it was who ‘chiefly endeavoured to alleviate that fatigue which his infant limbs were unable to bear, who heard with pity his unavoidable complainings; who fed him when he had wherewithal to do it; and who lulled his weary soul to rest.’ For his part, Tom had taken on a measure of responsibility, and towards the end of each day, when the men went off to collect molluscs, he was left to keep the fires alight.

All through October their little band trudged on across open country. This stretch of coast has since become a favourite of holidaymakers, with the retreats of Port Alfred and Kenton on Sea set amid more than fifty miles of perfect beaches fringed by dune shrubs. The sailors crossed the Bushman’s River, and met Thomas Lewis, a seaman who had been with another party, only to be left when he fell sick. Although urged by Lillburne to join them, Lewis said he could bear no further hardship or fatigue and had decided to head inland to the nearest kraal and throw himself on the mercy of the Xhosa. Sure that he was doomed, they carried on and soon passed – oblivious though they were to it – the spot where, in 1488, Bartholomeu Dias had landed as the first mariner to double the Cape. A few days later, and again unknowingly, they entered the most treacherous part of their trek.

What the sailors called ‘the sandy desart’, begins a few miles east of Cape Padrone and runs towards Algoa Bay as far as the Sundays River. It is not very considerable as deserts go, about forty miles of coastline in length, extending inland between one and four miles, and is now known by the benignly bucolic name of Woody Cape Nature Reserve. It is nevertheless a true desert, barren of water, with heavy, energy-sapping dunes 100 feet high. Had Lillburne followed Lewis’s example and struck inland at this point, they too would have come upon friendly Xhosa and their story would have had a different end. As it was, they could no longer bear to turn their backs on the sea that had fed them. Tramping along the beach, they may not even have noticed how the shrubs on the dunes thinned out and disappeared. By then they were in the desert, stumbling along in sand that sucked at their feet and made each step a labour. After a while they abandoned the effort; henceforth they would walk only when the tide was out and the sand was firm under foot.

On 2 November, after a night near Cape Padrone, both Lillburne and the lad were unable to get up, having eaten what seems to have been some rank whale meat. Lillburne asked his shipmates to stay with them for a day, just long enough for him and the boy to get over the worst. The others agreed. After another night Lillburne was better, but Tom was not. Once again, the steward prevailed upon the others to wait. They must have known that there was no hope, but all agreed. During the day Lillburne scanned Tom’s face for signs of improvement. He had made clear that he would not leave without the boy, but his vigil would be a solitary one, for the men had said that if Tom were no better in the morning, ‘they would be under the disagreeable necessity of leaving them’.

Carter painted the scene around the fire that night, as it was described to him: two ragged sailors attend in attitudes of prayer; a third proffers morsels of food; the faithful Lillburne comforts the unconscious child. Carter said that he did his best to portray his subject ‘in as just and striking a manner as my abilities would enable me’, but in his hands the child became an incongruous as well as unconvincing figure, a rigidly reclining ‘Blue Boy’ in satin suit and ringlets. Carter had overlooked the fact that Tom was Anglo-Indian.*

When they awoke in the morning, Lillburne left the child to sleep a little longer while they rekindled the fires and mustered a rudimentary breakfast. On going to wake him, the steward found that the curled up body of Tom Law was cold.

The mission of saving the boy had been the only thing keeping Lillburne going. All the men were profoundly depressed, but he simply gave up. Far from being a burden, the lad had become his purpose. According to Hynes, ‘it was only with the utmost difficulty that his companions got him along’ at all.

That day Robert Fitzgerald drank two shells of water, then ‘laid himself down and instantly expired’. In the afternoon, William Fruel said he could not go on and was left.

The next day was 6 November. It was exactly three months since the wreck. They had eaten and drunk nothing for two days. Henry Lillburne stopped abruptly amid the dunes. For a moment he stood motionless, then fell. He never rose again.

Carter’s verdict on the steward was that conduct ‘so humane and generous will most assuredly atone for many a misspent hour’. Reading his account, Dickens was struck how the child had been ‘sublimely made a sacred charge’. His own version of the story, in an essay from 1853, ‘The Long Voyage’, provided a liberal and characteristically sentimental improvisation of the facts. Describing how Lillburne had accepted guardianship of the child, Dickens wrote:

God knows all he does for the poor baby; how he cheerfully carries him in his arms when he himself is weak and ill; how he feeds him when he himself is gripped with want; how he folds his jacket round him, lays his little worn face with a woman’s tenderness upon his sunburnt breast, soothes him in his sufferings, sings to him as he limps along, unmindful of his own parched and bleeding feet.

But if the author was betrayed by his tendency towards mawkishness, his judgment on Lillburne was none the less apt. The steward, wrote Dickens, ‘shall be re-united in his immortal spirit – who can doubt it! – with the child, where he and the poor carpenter shall be raised up with the words, “inasmuch as ye have done it unto the least of these, ye have done it unto Me.”’

Of Tom’s companions only Hynes, Warmington and Evans remained and all were nearing the end. After a third day without water, they began to drink their own urine, and ‘when any could not furnish himself with a draught of urine, he would borrow a shell full of his companion who was more fortunate, till it was in his power to repay it’.

Their state may have left them susceptible to hallucination, for there is a surreal quality to an incident related to Carter by one of the survivors. On the beach, he wrote, they found one of their former shipmates dead, face down in the sand with his right hand cut off at the wrist. This man had supposedly been given to exclaim: ‘May the Devil cut my right hand off if it be not true.’ No further explanation was offered for an episode that had, perhaps, a touch of the seaman’s love of allegorical yarns about it.

The following day even their urine was exhausted, and they started to think the unthinkable. For the first and, so far as is known, only time, the custom of the sea was raised. Warmington said they had no chance together. Only by casting lots to determine who should be sacrificed might the other two survive by drinking the loser’s blood and eating his flesh. Hynes, grown by his own admission ‘so weak that he was almost childish’, burst into tears. If he should die, he said, his companions might dispose of him as they saw fit, but while he could stand he would never submit to the drawing of lots.

The practice had long been an unspoken code among seamen. As recently as 1765, the starving crew of a cargo vessel, the Peggy, disabled and drifting in the Atlantic, had first butchered and eaten an African slave, then agreed to draw lots to decide who would be next. It fell to a foremastman named David Fell, who asked for a day to prepare himself for death; although his mates agreed, the strain of the impending sentence overwhelmed him. The next day the Peggy was sighted by a rescue vessel; Fell, however, had gone insane.

Nothing other than rescue would have saved the Grosvenor trio either. Warmington said that if they would not draw lots, he could go no further. Hynes and Evans shook him by the hand, and left him. They had not gone far before spotting something that, in the haze that now blurred their vision, they took for large birds but turned out to be four men, remnants of the other band from whom they had become separated at the Great Fish River.

They too had remained loyal to one another. The boy Price had repaid Di Lasso many times for saving him at the wreck, having become an able scavenger and scout. Leary and a man named Reed, the armourer, were also alive, but Price’s great friend William Couch had died a few days earlier. At that point, Price told the inquiry, ‘they buried him and said prayers over him; and shook hands, and swore they would never separate again until they got into a Christian country’.

Price had a gift for finding water and had just located a fresh spring. The desperate Hynes and Evans were guided to it, while two men went back to collect Warmington. For the time being they were a party of seven, but before proceeding, a decision was taken to go back to Lillburne’s body. There was to be some suggestion that they intended to cannibalise the steward, although Hynes stoutly maintained they only wished to take his clothes. The result, however, was the loss of another member of the party: Evans and Reed set out but only Evans returned.

The remaining six went on. Now, on long stretches of beach, no mussels were to be found, but by watching how seabirds pecked at the sand, they found a variety of cockle. These creatures burrowed almost as rapidly as the men could dig for them, but they were reasonably plentiful.

In about a week, the men were rewarded with a sight of distant green hills: they had reached the end of the desert. Ahead, Algoa Bay opened out to the far hazy point of Cape Recife. A couple of days later, their mood brightened further when they came upon a whale carcass. Intending to exploit this resource to the full, they established a camp in a nearby thicket that provided shelter and water.

In the morning Di Lasso was sleeping under a bush and Price was on a hill looking for fruit, when he spotted a man whom, as he later related, ‘he first took for one of his companions’. Then he saw the gun on the man’s shoulder. ‘Immediately he ran to him as fast as he could, which was not fast, his legs being swelled, and fell down at his feet for joy, and then called to De Larso.’

Price could make no sense of what the fellow said, but Di Lasso established that he worked on a Dutch farm. The newcomer, who turned out to be a Portuguese named Battores, cast a horrified glance at the chunks of foul-smelling whale flesh that these apparitions had harvested so avidly, and then told them of the comforts that awaited them at the nearby homestead of Mynheer Christian Ferreira, whereupon

the joy that instantly beamed forth in every breast [was] scarcely to be conceived. And the effects it produced were as various as extraordinary. Every faculty seemed to be in a state of violent agitation: one man laughed; another cried; and another danced.

The date was 29 November 1782. One hundred and eighteen days after being wrecked, and having walked a little less than 400 miles, the first six Grosvenor survivors had reached safety.