A horse is a projection of people’s dreams about themselves — strong, powerful, beautiful — and it has the capability of giving escape from our mundane existence.

• • •

PAM BROWN

LEADING A HORSE IS the best way to assess the amount of chi we generate as handlers. There’s a bubble, a force field of energy, around us, as there is around all life forms. Some days, when we are feeling strong and positive, that bubble is large and energized. Other days, perhaps when we may be sad or anxious, the bubble around us is contracted, giving off a confused, weakened aura. Horses are very responsive to the quality of the aura given off by our internal emotional state.

IN A HERD OF HORSES, each member emanates a unique bubble of chi, almost like a fingerprint. Each individual is acutely aware of not just his own bubble but also when his bubble may encroach on or encounter others. Horses are keen managers of chi. The extent to which one horse’s bubble probes, imposes, or intrudes on another’s is no accident but a measure of that horse’s power and position in the herd’s hierarchy, a collection of closely knit, energetic beings.

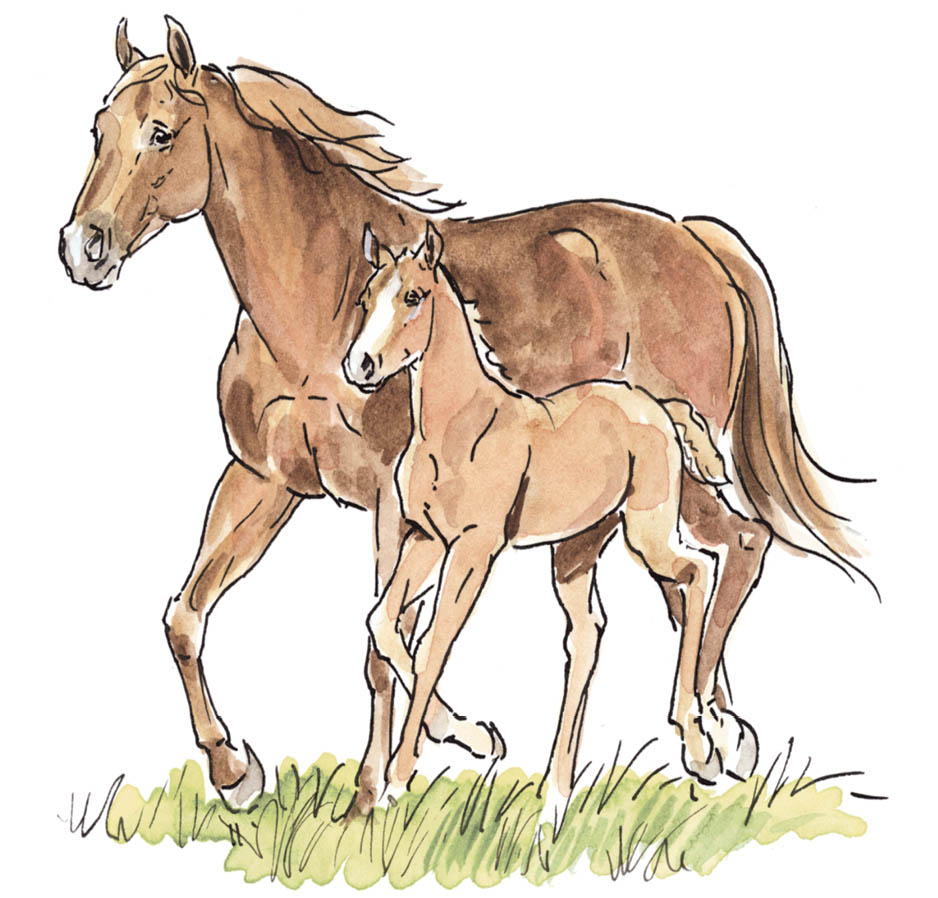

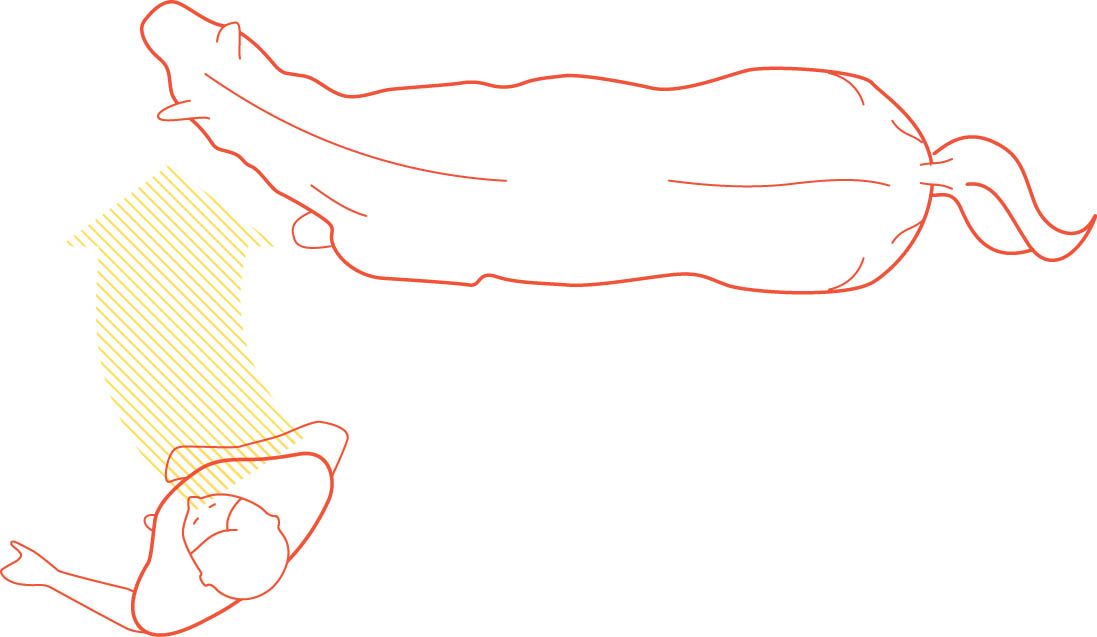

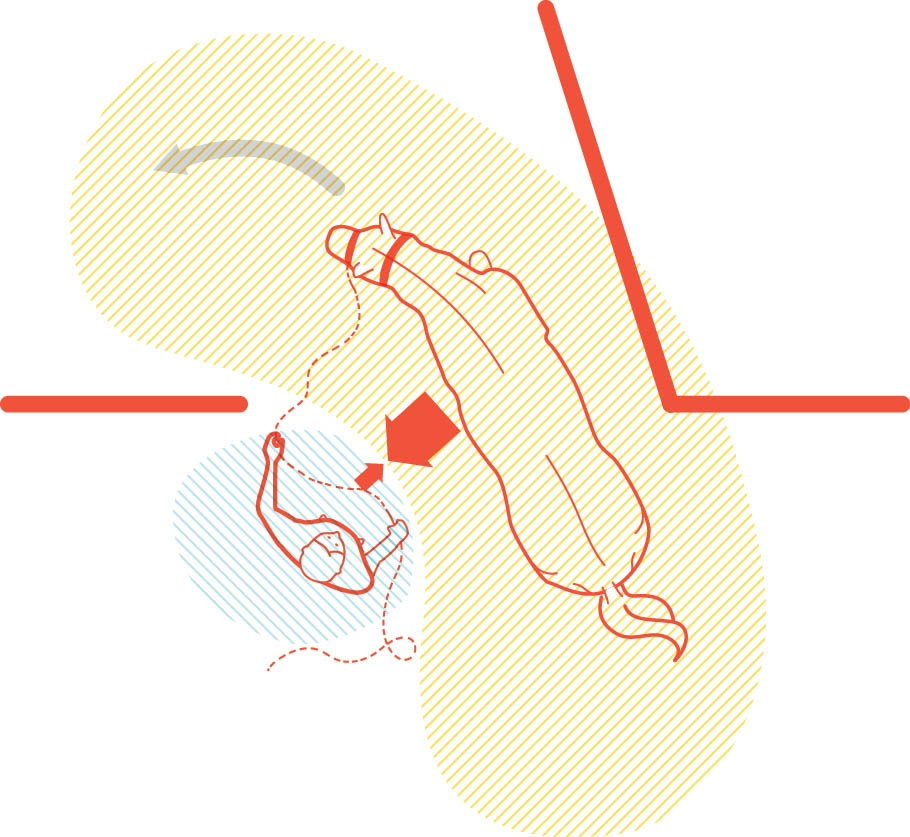

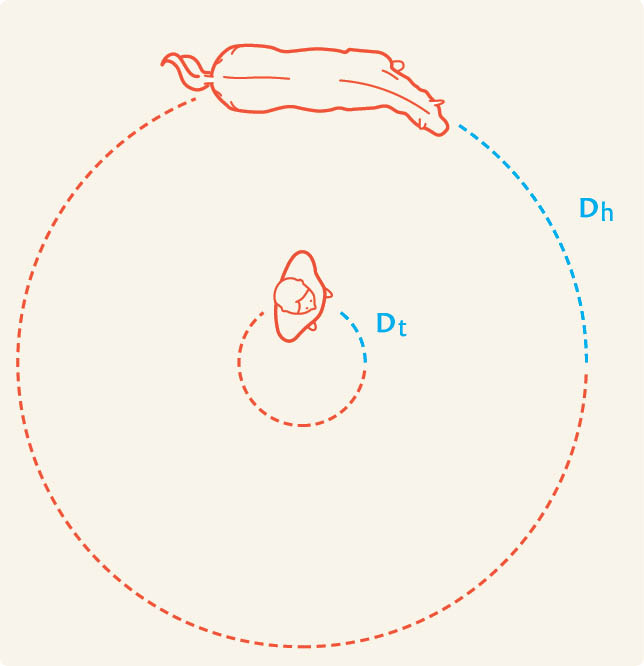

Every horse also sees his human handler in the same energetic context. When we are leading a horse, he will try to detect how much chi we generate in the first few steps we take (see figure 12.1). If it’s a first-time encounter, then leading is a critical first assessment on the part of the horse that serves to size up our energy status.

Within a few strides, the horse will start nosing closer to us, crowding us from behind, and probing our space from alongside our inside elbow. If our chi has a dominant, energetic pattern, the horse will back off and quickly fall in behind us. Alternatively, if the horse senses our chi is vague, weak, or indecisive, he will assert himself by genuinely encroaching into our space and pulling ahead, effectively seeing if he can establish himself as the leader.

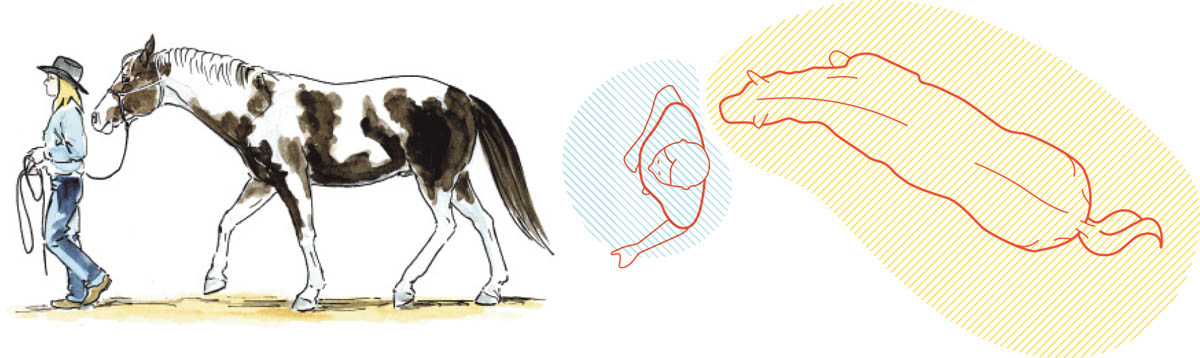

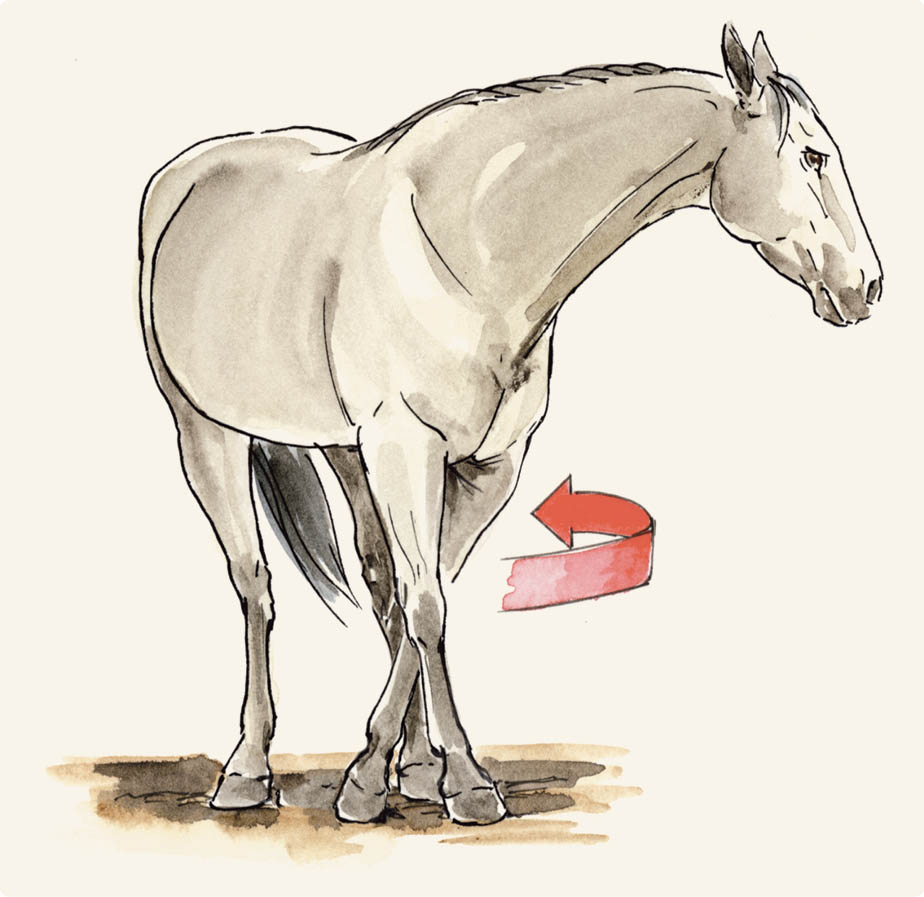

Bumping or jostling is how horses affirm their status in the herd. Such behavior is readily apparent, for example, when individual horses crowd around a flake of hay (see figure 12.2) to gain control of it. A dominant horse will assert himself by projecting significant amounts of chi against the more submissive adjacent horse.

As the dominant horse moves closer to the subordinate, he cranks up the amount of chi he is exerting. If the subordinate is already close to the flake, or actually eating it, then the dominant horse will drive him away by applying concentrated chi against his head, neck, and shoulder areas. This drives the submissive horse into a tight circle away from the flake of hay. We’re going to apply chi in a similar fashion to get our horse to circle away from us by pivoting on the hindquarters.

12.1 A horse uses the first steps of leading to probe the bubble of chi around the handler. Notice how the horse is probing behind the handler and then close to the inside elbow to detect how much chi she is generating

Even if you see and work with your horse every day of his life, he will still conduct a daily reassessment of your chi. It’s like trying to read what mood your spouse is in when he or she first gets that first cup of coffee. You put out feelers. You look for a sign.

Your horse does the same thing: he may crowd you at the gate, or stand too close inside your personal space, or just toss his head in your direction. None of the gestures are accidental; they’re all designed to test out your energy state, the status ofyour chi bubble.

IF YOU ARE LEADING your horse in a straight line (let’s say you’re on the horse’s left) and decide that you want your horse to circle away from you, to the right, you can hold up your right hand and forearm to block the left side of the horse’s face, as in figure 12.3.

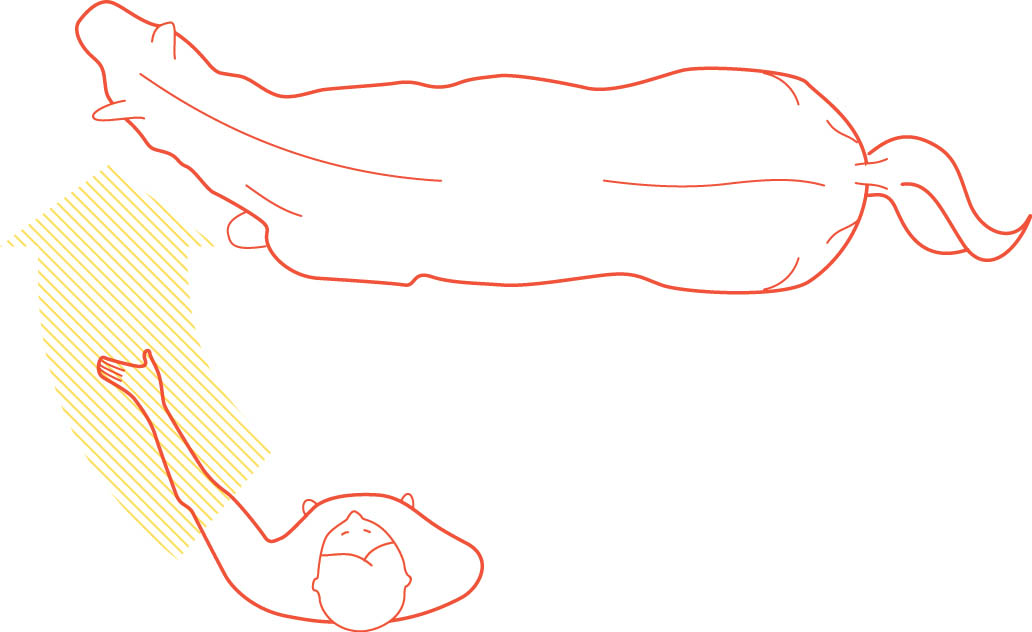

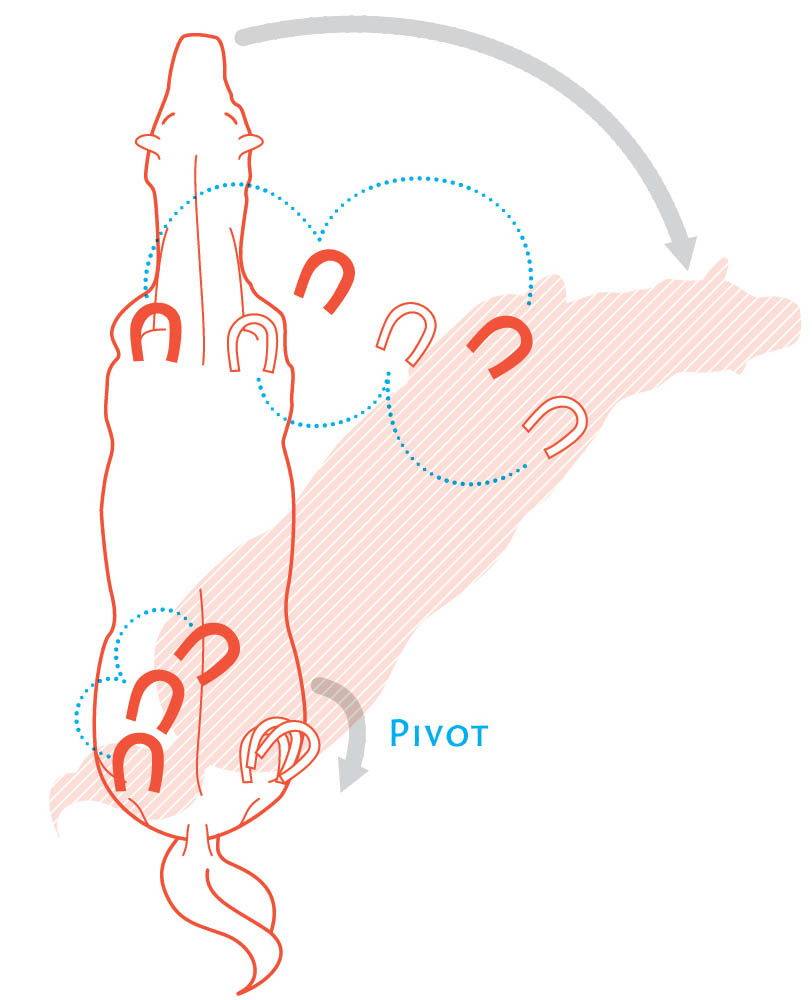

This gesture applies focused chi to drive the horse’s head, neck, and shoulders away from the handler. It sends a message to the horse to step away, just as the dominant horse did in the example of the flake of hay. Driving the horse over in a tight circle forces the horse’s forequarters to swing to the right (away from the trainer). This large shift in his center of gravity also makes the horse step over with his left leg, which usually passes in front of the right foreleg as the horse pivots on his right hind foot (see figure 12.5). The more sharply our chi drives the horse’s forequarters over to the right, the more the horse will have to rotate on the hindquarters to depart.

12.3 The trainer uses his hand to block and then drive the horse’s face, neck, and shoulders over to the right, causing the horse to step away from him

12.4 As the trainer’s use of chi becomes more adept, he can simply use his right or inside shoulder and elbow as the source of chi to shift his horse to the inside or to the right

12.5 Turning on the hindquarters. The horse steps over, his left leg crossing in front, with a pivot on the right rear hoof

This may sound like a lot of little movements for a trainer to control. But if our goal is to expand our awareness of how our own energy can interact with our horse’s to cause such maneuvers, then we must study our horse’s movements. We need to carefully analyze how our horse moves. If stepping across with the outside leg is part of the movement we’re asking our horse to perform, then we need to appreciate how we can pre-position our horse’s feet so the movement is easy to carry out.

Then if we’re asking our horse to initiate the outside turn by pivoting on his inside hind leg, we must precisely plan how, when, and where we will apply our chi to the horse’s face, neck, and shoulders to create the necessary shift in his center of gravity to make that turn happen. We’ll also amplify our chi as soon as we see our horse’s left shoulder begin to rise. It will feel as if we are assisting the horse to lift up his whole left foot, leg, and shoulder while pushing the entire forequarter over to the right (see box, below).

Each horse knows instinctually how to pivot on the hindquarters; this movement is part of his natural repertoire. Our difficulty as human trainers and handlers arises in getting the horse to carry out that maneuver smoothly and sequentially on our command, when we want it and how we want it. By studying the turn and breaking it down into its discrete components, we get a better grasp of how and where our chi needs to be applied to elicit the pivot from our horse. We learn to understand the balanced simplicity of the horse’s natural, four-legged, athletic choreography.

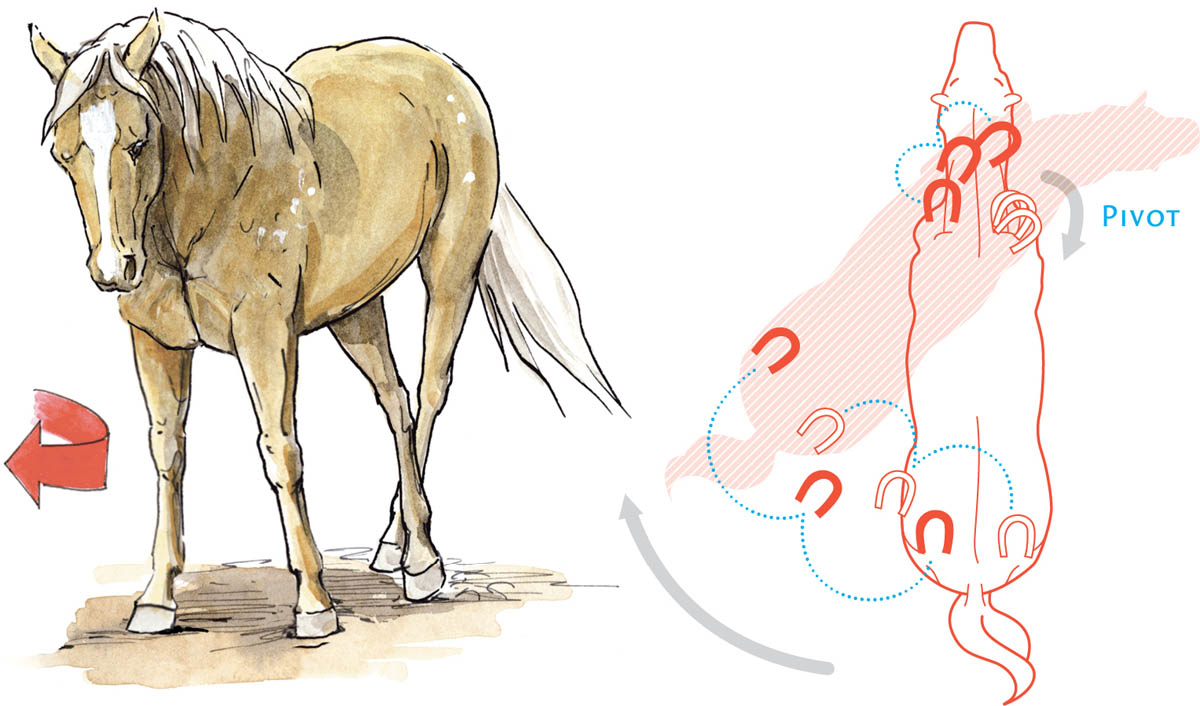

MOVING THE HIPS, or turning on the forehand (or forequarters), is an essential element of our horse’s repertoire not only for the purpose of moving the hind end over but also as an integral part of stopping. By turning on the forehand the horse is basically disengaging his hind legs, the main engine of propulsion. We will use this later to train the horse for both the casual stop and for the emergency stop.

For now, we will focus on positioning the horse’s legs in such a way that the horse can easily step over with the hindquarters, by passing the near leg in front of the far leg and pivoting on the inside front foot. In order to begin getting the horse to move its hindquarters over, we need to be able to apply chi to zone 4.

In this maneuver the ASK will simply be to lean and look at the hips. There is substantial chi being exerted by our eyes, and this will usually be enough to cause the horse to take a step over, first passing the near hindleg in front of the far one, and then bringing the far hindleg back into position next to the near hindleg.

For the REQUEST phase, we will crouch and assume a slightly more predatory, focused body position (or pose) as we look toward the hip. For the DEMAND phase we will begin shaking the end of our lead rope with the popper at zone 4 to move the hips over. Finally, the PROMISE phase is simple: we’ll give the horse a slap on the side of the near hip so he steps over.

The trick to moving the hindquarters over is to get just one step. This has a number of advantages. First, the horse is getting frequent rewards for side-passing with the hindquarters. Second, the trainer is learning to turn down his or her chi in order to get just one step instead of three or four. Finally, as we become more elegant in applying the chi to zone 4, we are able to gradually pulse it so that we can get one, two, or three steps or have the horse turn around on the forequarters in a full circle.

The point is to be able to pulse the chi against the hip for each step. If a horse gives you particular problems turning on the hindquarters, it can help to substitute a training wand for the lead rope. This will amplify the chi that you’re applying to the horse’s hips.

As our application of chi becomes perfected, so does the horse’s execution. The real training does not occur in the horse. The horse is actually teaching us how he carries out the movement in nature and then providing us with feed back as to how effectively we are applying chi to replicate the movement. As we get better, so does the movement. It becomes less awkward and jerky.

This is one of the essential values of working with horses, even for novices who have no real interest in how horses are formally trained. Each horse is a miniature laboratory where we get to experiment with different individual energetic combinations to see when and where we effect the largest improvement in his response. In doing so, our personal energetic awareness grows in countless ways.

The position of the horse’s front legs in turning on the hindquarters: note the distinct pivot on the right rear hoof.

PART OF THE MYSTERY and artistry of working with horses involves learning to appreciate how movement in one part of the horse engenders a reactive movement somewhere else. Sometimes I have to stop in the middle of training to remind myself of the exhilarating quality of this equine poetry in motion. Other times, I just hang my elbows over the fence and watch my horses in utter amazement as they chase each other in the pastures, running full out, exuberantly expressing the joy they must feel at being so alive, beautiful, and powerful. Don’t worry about the balanced poetry. The horse will take care of that.

Start with your horse standing still. Check the position of your horse’s hind feet to make sure you have positioned your horse to be able to step diagonally forward and across with the near hind leg. Now apply chi against the side of the hindquarters (zone 4). At first, you want a single step, even if it is a bit clumsy. The application of chi makes your horse sidestep with his rear end; the near hind leg crosses in front of the far one (see figure 12.7). Once your horse is accustomed to this maneuver, you can pulse your chi against his hip, asking for a second and a third step over with the hind end.

Eventually you’ll be able to get your horse to do complete circuits, pivoting on the forehand and walking his hips around in either direction. Look carefully for him to pivot around his planted inside foreleg. Eventually he should practically “drill” a hole in the ground with his near front hoof. You can help your horse at the earliest stages of this exercise by slightly flexing his neck to the inside, toward you. However, don’t rely on this pressure for long. Reserve using lead pressure on the nose for small corrections when asking him to tip his nose, head, or shoulder toward you.

12.6 Turning on the forequarter. The left hind leg steps over as the hindquarters shift to the left. The pivot point is the right front hoof.

WE HAVE ALREADY PUSHED our horse’s neck and forequarters over by applying chi alongside the horse’s face, not at the horse’s face. We want to aim our chi at the cheek, behind the muzzle and below the eye; otherwise our horse may get in the habit of jerking his head up. That’s just the opposite of how we want our horse to initiate the step-over with his front legs. We want our horse to drop his head, gently and smoothly flexed away from us, and then step across to bring his near foreleg across and in front of the far front leg and shift the forequarters away from us.

To carry out this maneuver, it helps to put your horse into the proper position. Prompt him by swinging his face and neck away from you. You accomplish this by applying pressure to the side of the cheek (away) with downward pressure on the lead rope. Pulling the lead downward puts pressure on the horse’s poll through the halter and helps your horse to flex down at both the poll and the neck (this gives you the downward component). Then gently push the near shoulder over with your hand. This helps him to understand you are asking him to cross over with the front legs. Insist the foreleg closest to you passes in front of the foreleg on the far side. Be generous with stroking and petting when your horse succeeds.

As your horse grasps the maneuver, gradually ask for more than just a single step. Keep mixing it up so your horse doesn’t fall into a rut. Sometimes ask for three or four consecutive steps and then just a single one. Throw in plenty of single-step exercises; they keep the horse light on his feet and teach us to be parsimonious with the amount of chi applied during each pulse. Too little, and your horse won’t move his feet. Too much, and you’ll get more than one step. Once your horse is working well to move off the hind- and the forequarters, consider laying down a little obstacle course to help improve your horse’s footwork.

AT FIRST GLANCE, the interactions of chi might seem more complicated as we move from leading to circling. They’re not. They’re simply more dynamic. To see how easily leading can turn into circling, go down to the stable. Bring a cup of coffee (freshly brewed, of course). Pull up a bale of hay. Sip. Watch. You will witness the invisible bubbles of horse and human bumping into each other like billiard balls.

Usually the horses are doing most of the driving. It’s only natural, I suppose. It would be much the same for Jedi knights from the Star Wars films. They would probably be very aware of the Force around them, while the rest of us, the non-Jedis, would walk around oblivious to its presence and power.

That’s how it is with horses. They’re zinging and zapping with chi all day long. It’s crackling and rippling all around them. I often become aware of all the energy flying around only when I tune into the horses and watch them at work and play.

Look for the pivotal moment when leading a horse evolves into circling. A good time to observe this is when people lead their horses out of a stall. The gate, wherever it leads — a stall, a pasture, or the round pen — offers a singular instant where we can see intention at work.

When a person is leading a horse up to gate (see figure 12.7), there are only two possible outcomes: the handler goes first or the horse does. About 75 percent of the time, the handler will go through the gate first. When the trainer is not paying attention, the horse gets through first. One thousand pounds customarily wins that one. If the horse pulls ahead through the gate, the handler will usually pull back on the lead. The horse will turn back around in a circle once he is through the gate.

12.7 This diagram shows what happens to a handler’s chi as the horse advances through a gate ahead of his trainer. Automatically, the trainer’s chi diminishes; the horse slips ahead and begins to circle in front of the trainer

Shifts in chi produce changes in the relationships of the ISLs. As the ISLs change relative to each other, we can predict how the horse will circle. In the top figure, the handler and horse are relatively balanced and moving straight ahead. In the middle figure, the human’s chi is diminished, and the horse slides ahead. He will circle in front of the handler. In the bottom figure, the handler moves in front of the horse, driving the horse to circle behind the handler.

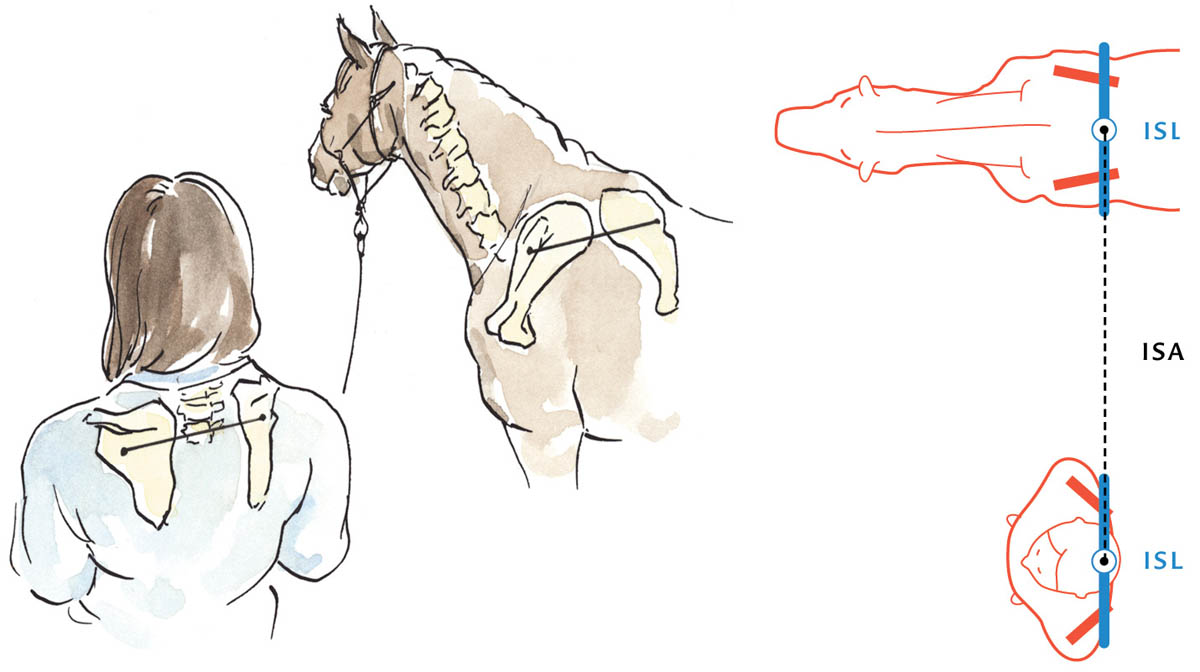

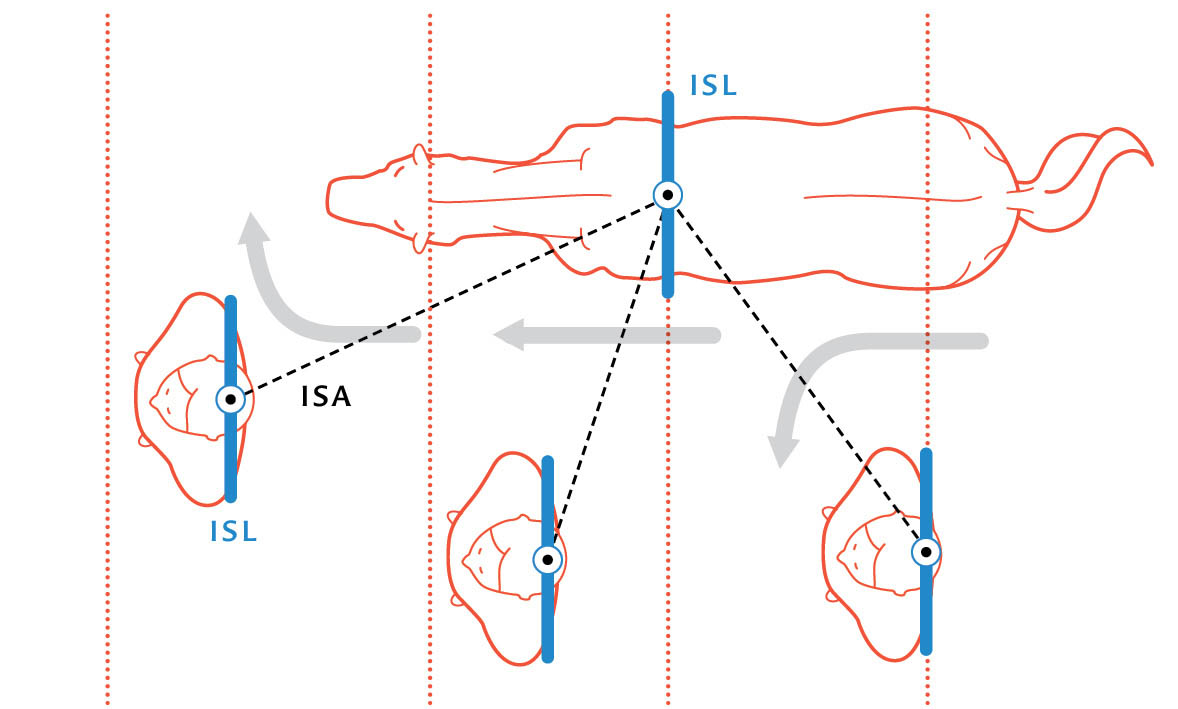

THE QUESTION ARISES: why does the horse automatically circle back so quickly? If we observe trainers closely, we’ll see that they walk slightly ahead of their horse’s left shoulder while leading him in a straight line. The trainer’s shoulder blades are lined up ahead of the horse’s shoulder blades. We can draw an imaginary line through the shoulders of the trainer and another through the shoulders of the horse. Each of these lines is called an intrascapular line (a line drawn between the shoulder blades of a single individual), or ISL (see figure 12.9).

We can draw another imaginary line starting from the center of the human’s ISL and connect it to the center of the horse’s ISL. We’ll call this the interscapular axis: ISA. Inter- signifies something shared or commonly held between creatures. So this ISA links the human ISL to the horse’s ISL.

When the handler is walking alongside the shoulder or head of the horse, roughly even with each other, the ISA is more or less perpendicular to the forward direction (see figure 12.8). The chi between the pair is balanced, and thus they move off, straight ahead.

If, however, the handler allows his or her chi to diminish, then the horse’s ISL will ease ahead of the trainer’s. Now the ISA slopes forward, and the horse moves off in a circle ahead of the trainer. In figure 12.11, the trainer is leading the horse from the left side. As the trainer falls behind the horse’s left shoulder, the horse will circle ahead and to the left. This is precisely what happens when the horse passes through the gate first.

As we pull up to a gate, our chi automatically decreases. Most of us just say, “Oh, well. The horse got there first. I’ll let him go through first.” That simple acquiescence automatically reduces our chi’s intensity. We shrink back a little to let the horse through, and the horse circles ahead of us.

Instead, if the handler increases his or her chi’s intensity while pulling ahead of the horse, the ISA slopes far behind the trainer. This will make the horse circle behind the trainer. Again, the horse will move to wherever the energy is lower; in this example, that is behind the handler. Now the pair will curve off to the right (see figure 12.10). The trainer goes first, and the horse slips behind into the procession.

This is how it’s possible to make our horse circle toward or away from us simply by increasing or diminishing our chi relative to the horse. Allow the chi’s intensity to drop, and the horse slips forward and circles ahead of us. Boost the chi, and the horse falls behind and circles behind and away from us.

12.9 The line drawn from one shoulder blade (scapula) to the other is called the intrascapular line (ISL). The ISL is shown for both the handler and the horse

12.10 The alteration in the ISA (i.e., the relationships between the handler and the horse) can change the direction of travel.

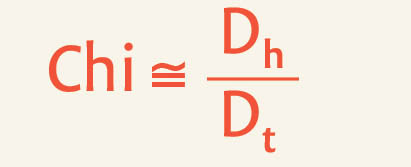

A critical facet of learning more about energetic connection through chi is to pay attention to your feet. The key to your manipulation of chi lies in mastering your feet: less feet, more hooves. The more proficient you become at manipulating chi, the less your feet have to move and the more the horse’s feet move in response to your intention. This resembles a mathematical formula:

Less feet, more hooves. The larger the Dh (distance traveled by the horse) and the smaller the Dt (distance traveled by the trainer), the more control the trainer is exerting through chi.

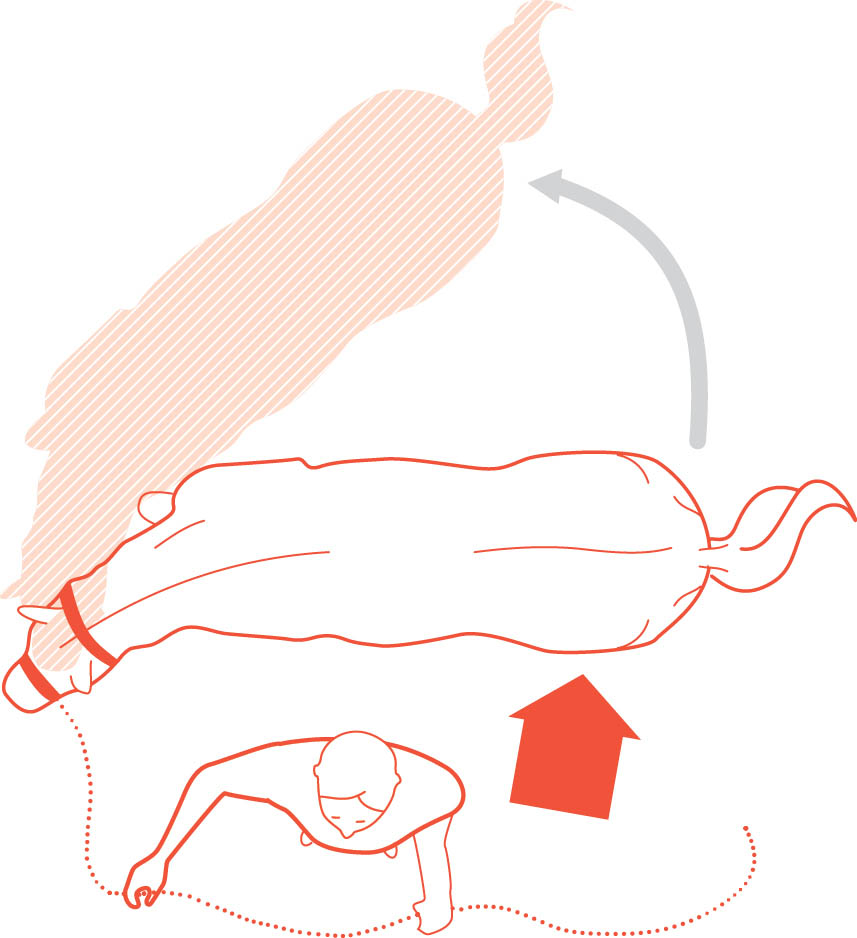

DIRECTIONAL REVERSAL is a wonderful little trick to learn at this stage. If your horse is pushy and seems to be always trying to lead (or reach every gate first), allow him to slip slightly ahead of you. Let him start to circle around your shoulder toward you. Now simply turn sharply inside, rotate 180 degrees around to your left, and then head straight off — dead ahead (see figure 12.11).

12.11 The handler uses directional reversal to turn inside the horse and get back into leading position

In effect, because the circle you are making is so much smaller than the one your horse is making at the end of the lead, you effectively turn more tightly and get “ahead” of your horse. You return to an assertive, balanced position where you can lead off again in a straight-ahead fashion. This simple, fluid movement allows the handler to turn inside the horse. It is a perfect demonstration of how chi, applied at the right moment, in the right place, helps us effortlessly maneuver our horse.

We can also transfer chi from next to the horse’s shoulder, while we are walking straight ahead, and shift it to zone 4 (see figure 12.12). When we do this in combination with simply turning around in place, we effectively make the horse move around us.

12.12 When the trainer turns while placing chi on zone 4, the horse’s hips are driven over, so the horse effectively circles around the trainer

WE HAVE NOW EMPLOYED four methods to produce directional changes or circles while leading our horse:

It is important to practice these maneuvers. It conveys to our horse that we are developing control of the leading process. We decide how the team will move, when we go from moving ahead in a straight line to a circle, be it large or small. Also, we assert ourselves; no matter how hard our horse may try to pull ahead of us, we can always put ourselves effortlessly back into the leading position.

Harnessing directional reversal, in particular, has a dramatic impact on the horse, because in doing it we transmit patient, focused chi. As in aikido martial arts maneuvers, you’ve used the horse’s unopposed forward movement to put yourself back in position to lead.

Directional reversal has much to recommend it. It is a tranquil, gentle, and patient method of asserting directional primacy over our horse. There’s no physical struggle or coercion. Your authority is established by skillful, effortless changes in position. Often, spiritual leadership establishes itself through gentle, nonviolent action rather than an obvious demonstration of power.

SOME TRAINERS MAINTAIN that horses are inherently lazy. This is false. What they label laziness is actually a potent survival mechanism: conservation of energy. True, given the choice, a horse would rather move from one end of the arena to the other at a walk rather than a gallop. But there’s no laziness in such behavior. By analogy, if I brought a cup of tea down to one end of my house and realized I’d forgotten my newspaper in the kitchen, would I sprint to retrieve it? If I just walked, would you label me as lazy? No. I walk for the paper and run if the house is on fire.

Over thousands of years of history, horses have, in fact, shown themselves to possess a mythic work ethic. The self-sacrifice of horses on behalf of their human masters is legendary. Human civilization has been carried on the backs of horses. Our temples, our palaces, our fortresses all stand on foundations laid over the bones of millions of horses.

My grandfather helped me understand the utter horror that engulfs horses caught in the grasp of murderous modern warfare. He was a cavalry officer in World War I, a conflagration in which more than four million horses perished. My Opa had the misfortune of having both of his horses shot out from under him in the midst of battle. It was also his great luck that those two horses gave their lives to save his.

Decades after the war, when I was about twelve, my grandfather took out a leather box from his writing desk. Inside, there was a spectacular medal. He handed it to me: a beautiful red and white enamel cross, wreathed with gold, hanging from a wide red and white-striped ribbon. To my eyes it shone greater than any jewel.

“This is the highest decoration my country, Austria, gives for valor,” he said. “This medal was placed around my neck by the emperor himself, in the Reduntensalle of the Habsburg Palace in Vienna. I received it after I was wounded and my second horse, Otto, was killed. Many people thought I was a brave man, I suppose. But let me show you something.”

He lifted the velvet backing of the box. From under the liner, he took out a small black-and-white photograph, not much larger than a postage stamp. It was a picture of my Opa as a young man. He was dressed in uniform, sitting proud and tall astride a beautiful dark horse. He placed the photo on top of the medal in my hand. (see figures 12.13 and 12.14.)

“This was my Otto,” he said. “Look at him! His strength and carriage. His absolute loyalty.…” My grandfather’s eyes welled with tears, and his notoriously resolute voice became tremulous. “The absolute loyalty Otto displayed … was remarkable. I told your Oma, before I went off to the front, that she need never worry about my well-being. I would come back alive because Otto would be there to look after me.” Tears rolled down his cheeks.

I handed back the photo. He collected himself. “Otto deserved this medal. He saved my life. He shielded me from the shell. He laid down his life for me. He died because … because he loved me.”

When I was older, my grandfather shared more details with me. He told me that although he himself had been injured by the artillery blast, he was able to rise to his feet. He recovered his bearings in the midst of the smoke and confusion of the battle and rushed over to where his horse lay. Sadly, two of Otto’s legs had been completely amputated by the blast, and his abdominal cavity had been torn open by shrapnel.

It must have been a sickening scene. My grandfather threw his arms around Otto’s neck and kissed him. Sobbing, he pressed his revolver against the side of Otto’s head and ended his suffering. I can only imagine how Opa felt having to kill his beloved companion.

A few years later Opa took out the medal again and gave it to me to keep. Forever. It was the last time we saw each other. Reading through some of his journals from that period, I think he had an inkling the end of his own life might be near.

“When I saw the Emperor standing there smiling,” he said, “and my family there, the generals, officers, friends, all filling the hall in the Habsburg Palace — I could think of nothing else but Otto. None of it,” he stated emphatically, “was worth losing Otto. Much too high a price, my boy,” he added wistfully. “I never would have agreed to pay it, had I known.”

“You mean Otto?”

“Had I known what was going to happen to Otto … to horses. To friends. Enemies. I’d never have gone. I’d have found myself a clever desk job in Vienna. Then I could have been riding Otto in the park every Sunday. He’d never have been … sacrificed.”

You can imagine how my grandfather would have reacted if someone suggested to him that horses were lazy. No, horses have a great sense of duty and hard work. But they need to conserve energy; they evolved into large foraging prey animals that must be ready, in an instant, to exert themselves explosively to avoid a predator’s attack. They save their energy for when it counts.

You employ this conservative trait when you train with directional reversal (see figure 12.11). A horse uses less energy moving in a straight line than when he has to stop, turn, and start up again. Every time a horse pulls ahead of you, slipping out in front of your ISL, you apply directional reversal. Eventually, the horse figures out he’ll expend less energy if he stays behind and just lets himself be led in a straight line.

To make this concept easier to grasp, test it out. Find a reasonable stretch of lawn or open space somewhere. Pick out roughly a 100-foot long stretch and walk it back and forth once, for a total distance of 100 feet. Now mark out a spot that is only 20 feet away and go back and forth five times, to and fro, until you have again walked a total length of 100 feet. You’ll discover that moving forward in a straight line uses far less energy than multiple round trips.

With some horses, directional reversal takes time to sink in. But there is no physical struggle or tug of war between trainer and animal. You should employ directional reversal every time your horse tries to muscle himself into the leadership role (and he will). Especially early on, directional reversal causes the horse to use up energy. The horse begins to see it is futile to try to pull ahead because you, as the handler, simply spin around and lead off. The horse soon realizes it makes more sense to simply follow. What’s more, you have let your horse learn this lesson for himself. Your horse will see that you demonstrate control, command, communication, and compassion as leader.

THE NOTION OF “PUSHING” OR “PULLING” with chi has nothing to do with mechanical energy transmitted through the lead or halter. It relates, instead, to the chi — the psychic vitality — emanating through the trainer’s arm and shoulder nearest the horse (see figure 12.4).

It takes about ten times more chi to push than it does to pull a horse in the same direction. Because it is more difficult to master pushing than pulling, I recommend learning first how to pull with chi before learning to push with it.

Leading your horse forward is the most straightforward “pulling” task you can tackle. Imagine a string running from your right shoulder to the tip of the horse’s muzzle. As you step forward, this invisible string pulls your horse forward. Keep your chi moving in a rhythmic, bouncy fashion. It helps to exaggerate your gait in a kind of sailor’s swagger while you lead your horse. The horse is sensitized by the small pulsing movements of your right upper torso.

Bring up the swing of your gait slowly and gradually. Accompany it with soothing verbal encouragement so your horse has some lighthearted fun with it. Be patient while playing this game and teaching your horse to move into the vacuum of chi you leave behind. There will be occasions, especially early in the process, when leading off by pulling with energy can break down a bit. Horses get bored. Their attention drifts. Like humans, the younger the horse, the shorter his attention span. If a horse loses the rhythm of leading, shrug it off. Start over or move on to something else. Never be afraid to return to the beginning.

Pushing is harder; it takes more practice. The focus of the practice is to first learn to predictably drive the horse’s face and shoulder over. Over time, you can reduce the need to hold up your hand to help project chi powerfully. Gradually you’ll bring the chi down into your elbow and shoulder and learn to drive the horse over with just the chi focused in your elbow.

Watch horses interacting with each other in the wild. This is one of Monty Roberts’ enduring contributions to the field of horsemanship: trainers should rely on direct observation of untamed horses (like wild mustangs) in their natural state to understand the methods horses use to communicate with each other and to teach each other. Pure Equus is spoken out in untamed, open spaces. Roberts insisted that natural training methods must use the same basic vocabulary, based on the horse’s body language and behaviors in the wild.

Not all of us can spend days in the field watching wild mustangs through binoculars the way Monty did. But you can watch chi at work between a mare and her foal in a stable. Within a matter of hours after the foal’s birth, the dam is able to direct her foal forward, backward, sideways (laterally), and even upward and downward, if necessary.

As she teaches her offspring vital survival skills, there’s only the lightest physical contact between mare and foal. A mare does not nudge hard or shove her foal outright, except in a dire emergency. Almost all physical contact between the mare and her foal consists of stroking or nuzzling for reassurance. As you watch the mare teach her foal to lead off, she will cue the foal with — what else? — her leading shoulder. In fact, most foals position themselves right behind their dam’s ISL (see figure 12.15).