By the mid-1770s Whitby’s shipbuilding trade was flourishing. No ‘seaport town in England’, wrote Lionel Charlton, builds the ‘number of merchant ships annually equal to those we launch and fit out at Whitby’.1 A typical year saw twenty-four or twenty-five new ships launched into the Esk. Almost always they would join the swelling flocks of barks and cats, bound to the coal wharves at Newcastle and thereafter to London. Less than twenty colliers had sailed in convoy with the Earl of Pembroke on her first voyage in 1764, but already by the 1770s there seemed something quaint about so small a fleet. Hundreds of sail soon clustered in the lower reaches of the Thames Estuary, waiting for a tide to carry them upriver. At the start of the sailing season in 1775 the newly launched colliers, with their sanded decks, gleaming sides, freshly stitched canvas and bright Union Jacks fluttering from their ensign staffs, were carried on their passage up the Thames past an unusually shabby old bark, lashed alongside near the Woolwich dockyard.

On 17 March 1775, as Franklin was gathering up his belongings at Craven Street, a man called George Brodrick was corresponding with the Navy Board. Brodrick was one of those innumerable Thames-side operators: ear to the ground, alert to profit. In the last month he had seen adverts listing Endeavour for sale. Looking over the old storeship he had seen four hand pumps, ‘with their proper Geer’. These were the pumps that had worked through the night on 10 June 1770 – had they not existed, perhaps British Australia would not have either – but returning to the storeship later, Brodrick had found the pumps and the gear stripped away. Irritated, Brodrick wrote to the Navy Board. The storeship ‘had a large quantity of water in the Hold, which without the pumps cannot be got out’.2

Brodrick’s letter painted a sorry picture. The rot had long set in. During her years of voyages to and fro across the Atlantic, Gordon might not have cosseted her but he had kept her in a seaworthy state. But since her last return from the Falklands no new purpose for Endeavour had been found and the funds for her upkeep had dried up. Neglect was fatal to ships. An accident might appear much worse, but abandonment was the surest way to ruin a vessel. In January 1774, for instance, Endeavour had been driven ashore at Sheerness in an alarming episode; nothing bad had come of it and Gordon soon had her sailing again. In comparison the entire winter laid up in the Thames had proved ruinous. Water was seeping in through broken seams in her outer carcass. The hold was now a basin of filthy river water. Oak was valued for its strength but it did not stand constant submersion. It was only a matter of time before the rot spread from her floor pieces and outer planking, into her knees and futtocks. Then that really would be the end. In February 1775 a survey had been carried out by the Woolwich Yard officers. A letter had come back to Stephens, the Admiralty secretary, that Endeavour needed ‘a middling to large repair’ which would take six weeks. Unwilling to put up the money, she had been advertised for sale.3

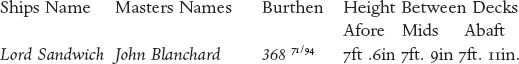

Endeavour’s story may have ended here. Exhausted, she could easily have been broken down for timber. She was a not inconsequential size at 368 tons – bear this figure in mind – and she contained a correspondingly large amount of oak. Ship breakers were adept at salvaging valuable pieces to sell on. Also appealing were Endeavour’s unusual embellishments: the doors to her cot cabins, some old furniture, her stove and interior wood that might be clawed out for further profits.

Brodrick, though, seems not to have been a scrap merchant. What precisely happened to Endeavour from March to November 1775 is not entirely certain. The last of the Royal Navy records confirm that she was sold for £645 on 7 March 1775.4 Brodrick was clearly involved in the transaction. He might have been acting on behalf of the new owner, or he may even have been the owner himself. Shortly afterwards come two tantalising mentions in the shipping catalogue Lloyd’s Register. On 6 May an Endeavour sailed for Newfoundland from Poole in Dorset with the master’s name ‘Blanchard’.5 Although there were many merchants’ ships named Endeavour, the connection with the name ‘Blanchard’ is significant for reasons that will become evident.

A second mention comes on 27 October, 1775, when an Endeavour arrived back at Gravesend after a voyage to Archangel in the Russian Empire. This ship had been sailing in company with another called Constant Friends, the master’s name, ‘Brodrick’.6 More than 3,000 miles separate Newfoundland and Archangel and it seems unlikely Endeavour visited both. The summer of 1775, then, is an ill-defined moment in Endeavour’s life. No longer a ship of the Royal Navy, all that can be said for certain is that she, like events around her, remained in motion.

News of the violent confrontations at Lexington and Concord had reached Britain by the start of June 1775. On 1 July, King George III wrote to Sandwich. ‘I am of his opinion that when once those rebels have felt a smart blow, they will submit; and no situation can ever change my fixed resolution either to bring the colonies to a due obedience to the legislature of the mother country or to cast them off!’7

The time for peace treaties or conferences had concluded. Many relished the prospect of the conflict to come. ‘The nation (except some factious and interested opponents)’, Sandwich wrote to one of his admirals, ‘are in a manner unanimous in their resolution to crush the unnatural rebellion that has broken out in America by force of arms, which to our great concern we find now to be the only expedient left.’ After a decade’s bickering, there seemed some relief that lines had finally been drawn. But if the argument was to be decided by the military, then great logistical problems faced the British. Edmund Burke had pointed out the obvious in the Commons: ‘three thousand miles of ocean lie between you and them. No contrivance can prevent the effect of this distance in weakening government. Seas roll and months pass between the order and the execution; and the want of a speedy explanation of a single point is enough to defeat the whole system.’8

The truth of Burke’s words was already being demonstrated. Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy in North America, had little idea about what he was expected to do. In Britain his ineffectiveness was already irritating the public, and Sandwich spent much of the summer months writing jockeying letters, exhorting Graves to ‘exert yourself to the utmost’ and ‘show the rebels the weight of an English fleet’.9 He repeated to Graves the maxim: ‘you may be blamed for doing too little, but can never be censured for doing too much’.10 The absence of any clarity over British objectives, though, and the small size of his fleet, hampered Graves. Just one warship, a few frigates and a dozen sloops had been in America when he arrived on the station in April 1774. Little more had arrived since. As the king was writing to Sandwich of ‘smart blows’, Hugh Palliser was totting up a ‘disposition of the force’, needed to ‘annoy the rebellious provinces’. He thought twenty-two ships were needed for Boston – including three fifties – three for the strategic harbour at Rhode Island, then two fifties, three frigates and three sloops at New York. As marvellous as this sounded on paper in Whitehall, none of this existed for Graves.11

Sandwich’s naval reforms had been going forward well but he realised the danger of dividing his squadrons. The heaviest line-of-battle ships needed to stay in home waters, in case France or Spain, or a combined force, decided to capitalise on Britain’s overseas distractions. Warships were one problem, but an altogether more thorny one was troops. The king had resolved to put down the American rebellion in much the same manner his grandfather had quelled the Highland revolt of 1746. The rebels were to be obliterated. The British would attack like sharks before the rebellion gathered life. This year’s campaigning season might have been over, but George III wanted the next, 1776, to stand in history alongside other victorious years, 1415 or 1759, as one of decisive British success. To achieve this he needed a formidable army. British regulars alone numbered less than 20,000, and so were insufficient for the task. Naturally, then, the king looked abroad for reinforcements. Catherine the Great of Russia rebuffed him, but the traditional recruiting grounds in Germany bore fruit. By December 1775 contracts were all but signed with Charles I, Duke of Brunswick and the landgrave of Hesse-Kessel. Between them they agreed to supply the British with around 16,000 troops.

But here again was Burke’s snag. George II might have seen his army march to the north of Scotland, but it was something entirely different to transport an army across 3,000 miles of ocean to the scene of battle. An army was no light load. It was not only soldiers and weapons, but it meant tents, barrack furniture, coals and candles, specialist clothing, bags of flour and oats, casks of water and horses. ‘Our army … is healthy, brave and zealous’, wrote Admiral James Gambier, but ‘Twelve hundred leagues with its natural difficulties demand a solemn thought – the means and expense.’12

Usually the Admiralty did not trouble itself with transportation matters, but the vital nature of preparations during the winter of 1775–6 meant that Sandwich and, in particular, Palliser became actively involved. Only in February 1776 did the full extent of the challenge become clear. An army of almost 30,000 infantry and 1,000 horses was to be delivered to the North American shores for the beginning of the campaign season in the spring. A total of around 80,000 tons of transports were needed for the task.13 It was, perhaps, the steepest logistical challenge of the entire Georgian age. To meet it Sandwich and Palliser fell back on a tested tactic: hiring high-capacity colliers on short-term contracts. Finding a sufficient number of weatherly vessels, though, proved troublesome. To do so was vital. If the transport fleet was lost in unseaworthy ships, the whole campaign would be over before it had begun.

Sandwich, though, was optimistic. In a letter of 30 December 1775, he admitted:

Our disgraces have been great & repeated in America, but I am clear in the opinion I allways had, that they are entirely owing to our having begun too late, and having suffered ourselves to be amused by what were called concilliatory measures; fleets and armies, admirals & generals, can do very little without ships, troops, and orders; & the consequence of their having gotten them by slow degrees has been that we have been on the defensive the whole campaign … It is however our business to look forward & not to lose our time in complaints, the next campaign promises fair.14

Notices from the Admiralty were soon circulating in the northern ports, offering ten shillings a ton for the hire of colliers or other cargo vessels as transports, for six months certain. Lured by the bounty, day after day masters reported to Deptford, offering potential ships. To look through the yard’s books from late 1775 into early 1776 is to see the intensity of the work. Surveys were made: oak planking was inspected for faithfulness, rigging was examined, dimensions were jotted down, descriptions of vessels were sketched for administrative purposes. There was no time for deck plans or drawings. There were just two salient questions: was a ship seaworthy, and when could it enter service?

Still needing more tonnage, Sandwich looked further afield. In January he wrote to the king: ‘a thought has occurred … a large number of Transports may be procured at Hamburgh’, an idea Palliser ‘greatly approves’.15 In February Sandwich extended the search to Bremen and Lübeck. And then another agent was dispatched to Holland. ‘We flatter ourselves’, Sandwich told the king, ‘that as soon as it is known that we are determined to deal with foreigners, we shall get the better of the combination among the owners of Ships at home.’

At Deptford the work was relentless. The yard books show vessels being offered for charter each day. Inspections were immediately carried out, but they were not indiscriminate. A sizeable number of potential transports were rejected because of their structural defects. On 6 December the yard officers wrote ‘We have Surveyed the Endeavour Bark’, but found her to be ‘the same that was lately sold from Woolwich’:

the Officers of which Yard having we apprehend, prior to her being Sold, reported her Defects such as to render her unfit for His Majesty’s Service, and it appearing to us, that no Material Repair has been given her since, We cannot under these circumstances recommend her as a proper Ship, to be employed as a Transport.16

Among the four sets of initials at the foot of the letter, once again there is an ‘AH’, presumably of Adam Hayes. Hayes was still the master shipwright at Deptford. He could hardly have failed to recognise the bark that he had helped convert in 1768. He, uniquely so, saw the entire progression of the ship’s life. He had known the Earl of Pembroke, Milner’s bright, sturdy collier. He had seen Cook’s Endeavour, loaded with philosophical equipment and provisions for the South Seas. And now he witnessed the third major transformation in her life.

By the end of 1775 Endeavour was owned by a man called James Mather. Mather was one of three brothers from London’s East End who were active in the Greenland whale fishery and in supplying chartered storeships to the Royal Navy. Endeavour may have been defective and tired, but she was not beyond repair. After her rejection in early December, Endeavour was taken to a shipwright called William Watson. Three weeks after she had been rejected, on 27 December the yard officers examined the collier again.

Age uncertain, she is now under Repair, has many Timbers Rotten, and Wm Watson, the Builder, believes she was built somewhere to the Northward, she appears to be Old and defective.17

This brief note catches events in progress. The bark was not only being paid with pitch, repatched, dubbed, scrubbed and, perhaps, fitted with new spars, she was also being given a fresh identity. At some point over the Christmas week the decision was taken to eradicate the hindrance of a blemished name. If Endeavour was now remembered chiefly for her faults, then something different was required. As Thomas Milner had known in Whitby a decade before, a name could act as a political statement if needed. In this spirit a name appropriate to the time and to the service was selected: Lord Sandwich.

This shift in identity is documented in another of the Deptford yard books. It reads: ‘Lord Sandwich 2d: unfit for Service She was Sold out of service Called Endeavour Bark refused before.’ The sleight of hand would wrong-foot historians for centuries to come. Administratively speaking, Endeavour simply vanished in the Thames in 1775. The proof that Endeavour and Lord Sandwich were one and the same vessel, though, is not confined to a single line in the Deptford books. On 5 February 1776 a new survey was performed on the Lord Sandwich.

Here is evidence that cannot be refuted. When Milner sold the Earl of Pembroke to the navy in 1768, a similar survey had been carried out. On 27 March 1768 her burthen in tons had also been recorded as 36871/94 tons. The between-deck measurements – afore, amid and abaft – for the Earl of Pembroke in 1768 are also identical to those of the Lord Sandwich in 1776.18 In an age before standardisation, the likelihood of two vessels having precisely the same measurements is negligible. The Deptford survey of 5 February goes on to describe Lord Sandwich as a bark, ‘built at Whitby, and rep’d lately in the River, Bottom Sheathed, has rises to her Quarter Deck and Forecastle, is roomly and has good accommodation’.19

A subsequent examination was carried out on 9 February. This repeats the tonnage 36871/94 for Lord Sandwich. After this the yard officials felt confident enough to inform the Navy Board ‘we find her compleated, fitted and stored … and having all her Men onboard was ready to enter into Pay’.20

Leafing over the reports on his Whitehall desk, Sandwich might have smiled at the ship’s name. He was wily enough to spot a clever diplomatic ploy when he saw one. But he could not have guessed that his own name was only a veneer. History often conceals facts. Sometimes, however, through a long lens, it is possible to discern things that were entirely hidden to those closest to the scene. Reading the few lines of description, there was no way Sandwich could have detected that this was a bark that he knew intimately. All that mattered was that another 368 tons had been chalked off the total they needed to find.

For the Lord Sandwich – as Endeavour must now be called – February 1776 marked the most unexpected of new beginnings. Looking back it is striking to see how the arc of this ship’s life resembled the rise of the political strife in America. Her launch in 1764 came just months after the Sugar Act. Her purchase in 1768 happened as the colonists reacted to the Townshend duties. She approached New Holland as the Boston Massacre was taking place, and returned from her last voyage as the first Continental Congress opened. Now, after so long running in parallel, the bark’s life would interweave with events in America. In February 1776 she sailed down the Thames for the last time. Patched and plugged, she was no longer the weatherly ship of old that had completed one of the most iconic of solitary voyages. This next as Lord Sandwich would be entirely different in character, but it would turn out to be almost as historically significant.

In the words of one of his colleagues, the spring of 1776 advanced on Sandwich with ‘hasty strides’. On the south coast at Portsmouth, the warships, transports and auxiliary troops were expected to gather in April or May, so that the Atlantic crossing could be made in time for campaigns in summer and late autumn. News of the invasion force was reported in the newspapers alongside the accounts from America of a fiery polemic ‘lately published’, and attributed to one of the chief Boston agitators, Samuel Adams. Though it was not yet known, Common Sense was actually written by Thomas Paine, an Englishman who had travelled to Philadelphia some years before with a letter of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin. Paine had left Old England behind and he implored all other British Americans to do the same.

Small islands not capable of protecting themselves, are the proper objects for kingdoms to take under their care; but there is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island. In no instance hath nature made the satellite larger than its primary planet, and as England and America, with respect to each other, reverses the common order of nature, it is evident they belong to different systems: England to Europe, America to itself.21

Common Sense was quoted at length in the British newspapers. Most significantly it showed the personal animosity levelled at King George III himself. The quarrel had begun as a parliamentary one, but the king’s active encouragement in the suppressive measures and in his hiring of foreign mercenaries had outed him as a vile tyrant, a cruel and wicked tormentor of his subjects. Paine likened the king to ‘the principal ruffian of some restless gang’. Did the monarch guard against civil war? Plainly not. ‘The whole history of England disowns the fact. Thirty kings and two minors have reigned in that distracted kingdom since the conquest, in which time there have been (including the Revolution) no less than eight civil wars and nineteen rebellions.’ In 1776, Paine exhorted, ‘The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth.’ The ‘United Colonies’ had a chance ‘to make the world over again’. ‘We are endeavouring, and will steadily continue to endeavour, to separate and dissolve a connection which hath already filled our land with blood.’22

There were other signs that the Americans would not prove as timid as the British hoped. On the evening of 2 May, Sandwich was summoned to an emergency meeting of Cabinet by the Secretary of State for America, Lord George Germain. The news had reached London that General Howe – commander-in-chief of British armed forces – had been ‘obliged’ to abandon Boston, ‘for want of Provisions and from the position of the Enemy’. The full story – that Howe had been brilliantly outflanked by a provincial army led by General George Washington – was not included in Germain’s first letter to the king. This was perplexing for Sandwich. The previous autumn he had replaced Graves with Admiral Shuldham, who had assumed command only in January. It turned out that Shuldham’s first task was to evacuate Boston along with Howe’s 6,000 men to Halifax in Nova Scotia. With Boston fallen, the strategic focus shifted, inevitably, to New York.

Standing on the southernmost tip of Manhattan Island, like a toe at the end of a foot, New York had been a focal point in colonial America ever since the British had wrested it from the Dutch a century before. The population of 20,000 – twice the size of Whitby – lived in a little collection of orderly streets that stretched back from the shores of a massive deep-water bay. When the Dutch had first sailed into this bay in the early seventeenth century, they had been elated. Here was a ‘convenient haven from all winds, wherein a thousand ships may ride in safety’. The harbour’s position at the bottom of the Hudson River made it even more appealing. If British forces in Canada could secure the northern end of the corridor and a naval fleet could evict Washington’s forces from New York, then the British would be able to drive a wedge between the New England colonies and those in the south.

To further season New York’s appeal was its social composition. Two-thirds of the private property was believed to be Tory-owned with Queens County known in particular as a royalist stronghold. Until 1775 New York had been Britain’s military base and many in the army knew the woods, streams, marshes and rocky hills of Manhattan well. One officer claimed that Manhattan had ‘the finest & most romantic Landskip that the Imagination can conceive’. With theatres and balls in the city, and hunting in the countryside, half an hour’s ride away, New York’s appeal was complete.

With the Hudson or North River on one side, the East River on the other and the harbour to the south, it was obvious that whoever had naval advantage would be able to surround Manhattan on three sides. Did that make it impossible to defend? General Charles Lee of the Continental Army believed so. He wrote to Washington that the best they could do was to turn the city itself into ‘an advantageous field of battle’.23 Washington was more hopeful. He arrived in New York from Boston in mid-April and established his military headquarters on Broadway, the main thoroughfare. He was soon busy constructing defences. Washington had the advantage of time, but as everyone knew, he had no ships to compete with Britain’s. Since May 1775 the sixty-four-gun HMS Asia had been patrolling the harbour at will. ‘We expect a very bloody summer at New York’, Washington wrote to his brother on 31 May.24

Having recently replaced Admiral Graves with Shuldham, in February Sandwich had written to Shuldham with the ‘disagreeable’ news he too was to be replaced, or as Shuldham put it, made ‘the football of Fortune’.25 With the size of Britain’s fleet escalating, a figure with gravitas was to command. Vice Admiral Lord Richard Howe was the elder brother of General William Howe who was already leading the army. Lord Howe had a famous fighting reputation. He had entered the navy at thirteen, had sailed in Anson’s fabled fleet in 1740, had fired the first shots of the Seven Years War and had played a starring role in the Battle of Quiberon Bay. When war with Spain over the Falklands seemed certain, Howe had been appointed commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean fleet in response. The news that he was to command the navy in America had been announced with expectation. ‘Lord Howe is to have the command of the fleet against the Americans’, rang an article in the London Chronicle, ‘his brother being commander by land, the most spirited conduct is expected next campaign’.26

As Washington chased one Howe out of Boston, papers in England were tracking the progress of the other brother to Spithead where he was to go aboard his flagship, the newly launched HMS Eagle, a fine man-of-war of sixty-four guns. Rattling along the London Road too were four wagons ‘laden with money’ from the Bank of England ‘for payment of his Majesty’s ships and the transports’.27 The French, keeping a careful surveillance on preparations, were impressed. ‘It is not a small task to transport to America in a short time’ ran an intelligence report prepared for the foreign minister, the Count de Vergennes, ‘34 thousand troops, cavalry, ammunition, victuals, artillery, wagons, pack horses and all the paraphernalia required for the operations of such a large army which will land far away on an enemy shore, among fanatic people determined to destroy everything they will not be able to defend.’28

The scale was extraordinary but by April 1776 sufficient transports had been found for preparations to go ahead. To some it was amazing that such energy had been poured into so destructive a project. One satirical woodcut, The State Blacksmith Forging Fetters for the Americans, played on this. It showed members of the British government busily forging the chains that would shackle their subjects. North, Lord Mansfield and King George were hard with work, linking together the chains. Sandwich was at the centre of the mischief. He grips a hammer in one hand, an anchor in the other. Dark things were being planned from the gloom of the shop.

This is how Sandwich was viewed across the Atlantic, where his infamy matched that of Jemmy Twitcher’s at home. It was little wonder that a skirmish on the Delaware in May 1776 was reported with such glee, when HMS Roebuck was driven ashore. The Roebuck ‘was built last summer under the particular patronage of Lord Sandwich, whose favorite she is. – The Captain is also of his particular appointment’, went one newspaper piece. ‘Quere, What must his Lordship say of his ship, when he hears that she was beat by the “cowardly Americans” who have nothing but rusty guns, broomsticks, &c?’29

Nor was Sandwich’s conduct above suspicion at home. On 10 May 1776, the old Scottish philosopher David Hume was travelling by coach from Scotland to London when, at an inn near Newbury, he came across a party comprising Sandwich, Joseph Banks, ‘and two or three Ladies of Pleasure’, entertaining themselves on a fishing lake. The tone of the diversion struck Hume wholly at odds with the political atmosphere. He watched the sport as Sandwich ‘caught trouts near twenty inches long, which gave him incredible Satisfaction’. How incomprehensible, Hume pondered:

That the First Lord of the Admiralty, who is absolute and uncontrouled Master in his Department, shou’d, at a time when the Fate of the British Empire is in dependence, and in dependence on him, find so much Leizure, Tranquility, Presence of Mind and Magnanimity, as to have Amusement in trouting during three Weeks near sixty Miles from the scene of Business, and during the most critical Season of the Year. There needs but this single Fact to decide the Fate of the Nation.30

Hume’s was a noble but flawed reading of the situation. Sandwich had actually done his utmost to prepare the British response. His work had begun back in 1771 when he had vowed to reinvigorate a weary navy. His reforms may not have been completed, but he had had some success. For months he had been office-bound. Now, whatever could have been done had been done. Writing to the king on 23 May he reported ‘It is with particular satisfaction that Lord Sandwich can now observe to your Majesty that this great work of compleating the transports is now brought to a conclusion with less delay and difficulty than might have been apprehended.’31

Since the Middle Ages the German people had retained a reputation as a ‘pugnacious and warloving people’. Their disposition for valour, wrote one solider, ‘is woven into the spirit of the nation and stems from its very origin’.32 Fractured into its many principalities, this character was thought to be found nowhere more potently than in Hessen-Kassel. Situated in the German interior, among rough, wild hills and forests, the men of Hessen-Kassel were known as unusually ‘stout and strongly built’, features arising from a ‘cold but wholesome’ environment, and food that was ‘not luxurious but nourishing’. The ruling princes of Hessen-Kassel, the landgraves, had long turned their physical prowess to profit on the market, raising auxiliary armies to be rented out to the powers of Europe. For ‘Hessians’, soldiering was a way of life.

The Hessian knows that he is born to be a soldier; from his youth he hears of nothing else. The farmer who bears arms tells the son his adventures, and the lad, eager to tread in the footsteps of the elder, trains his feeble arms early to the use of formidable weapons; so when he has reached the size necessary to take a place in the valiant ranks, he is quickly formed into a soldier.33

Throughout the eighteenth century the landgraves’ best customer had been the British Crown. With a desperate need for troops in late 1775, it had surprised no one that George III had come calling again. Aiming to secure 4,000–5,000, the British had been delighted at the Hessian response. As many as 12,000 were ready to serve. Events had progressed at speed. By December 1775 a draft treaty was sent to London and by February it was concluded. ‘There is not common sense in protracting a war of this sort’, Lord Germain reasoned, ‘I should be for exerting the utmost force of this Kingdom to finish the rebellion in one campaign.’34

Pitting the drilled, effective, experienced Hessians against Washington’s assemblage of farmers, tradesmen and boys, many of them barely armed at all, was thought the best way of concluding the campaign rapidly. In mid-March 1776 the chartered transports began to sail from Deptford for the River Weser. On 23 March the mustered troops started to come aboard. Three weeks of delay followed. A thousand more Hessians had turned out than were initially anticipated with the result that two regiments had to be left behind. Having heard plenty about Hessian soldiers in the papers, the inhabitants of Portsmouth were able to see them for themselves in early May as they arrived at Spithead.

Among the First Hessian Division was a man called Albert Pfister, who wrote an account of their voyage. For all they flourished on the battlefield, Pfister demonstrates that Hessians were timorous sailors. Ever since their mobilisation the soldiers had fretted about the prospect of the ‘terrible ocean’. The dangers they foresaw soon arose. A fleet of a hundred ships, almost ninety per cent of which were transports, sailed under sealed orders on 6 May, shepherded by Commodore William Hotham in the fifty-gun Preston. The fleet had barely left Portsmouth when ‘an adverse and violent storm’ whipped up, throwing all into confusion. ‘No one could stand upright in the cabins, everything was tossed about pell-mell and sailors fell overboard and could not be saved’, Pfister wrote.35

Pfister’s description of the early days of the voyage recorded his initial human response to this unfamiliar piece of engineering. He was alive to the vibrations of his transport. He felt the exaggerated rolls or heaves of her body, as her shallow hull rocked in harmony with the ocean. This, as it had for Banks, made many Hessians seasick. But Pfister experienced the charms of sailing too. One night, after the winds had lapsed into a ‘perfect calm’, he stood in the moonlight as his transport climbed waves that ‘rose to an astonishing height’, her bows lifting towards the sky, before they crested the wave and raced down the back slope. He watched as ‘foam sparkled’ and ‘lightning flashed and quivered on the waves’.36

Picturing Pfister standing in the moonlight, an Atlantic breeze on his face, looking towards the strobing forks of light, it feels like we are looking at a Romantic of the years to come. But this was no Romantic solitude. All it took was for the sun to rise in the morning for the great fleet to appear again. Ships were strewn across the water. Leading the way was HMS Preston and Commodore Hotham, then there were four thirty-six-gun frigates and two fireships.37 These fighting ships guarded about ninety transports that carried, all told, about 12,500 land troops. Pfister was ‘astonished’ at this show of naval might. ‘Who may be the master of the ocean’, he wrote, ‘was made evident when a Danish and later two Swedish East Indian ships were passing through the fleet.’38 As they came into firing range, the merchants struck their flag and topsails in a sort of maritime curtsy.

The British fleet must have presented an awesome sight to the Swedish and Danish crews. In total size this naval force was barely smaller than the Spanish Armada of 1588. Gazing at it, the Scandinavian merchants would have known the outline of colliers from the northern seas, and they would also have been able to detect a looseness in their handling. Sailing colliers was always a matter of confidence. In careful hands they were dextrous enough, as Cook had demonstrated. But when manned with inexperienced crews, the commonplace became hazardous. Pfister saw one transport, Good Intent, ram into the bows of the Claudina, leaving a gash above the cabin. Others sailed so poorly they ‘oftentimes had to be taken in tow by the war vessels’. Another, Speedwell, was making so much water that Pfister thought it ‘doomed to sink’.39

But if the collier fleet looked ragged to the Scandinavian merchants, the trim order of the Royal Navy was not far behind. Five days after Hotham had sailed with the transports, Admiral Howe had left Portsmouth in the Eagle. ‘Made great Progress with a fair Wind all Night’, wrote Howe’s secretary, Ambrose Serle, on 15 May. ‘For the most part, we gained 7 and 8 Knots an Hour. The Ship rolled much, which made several of our People very sick: As to myself, I was very well, but could not do much Business.’

Serle would be an important eyewitness to the clashes that would follow. While he journalised in his spare time, in his working hours he kept on top of Howe’s administration. Keen-eyed, Serle maintained a regular list of the ships under Howe’s command. Perhaps it was Serle who wrote out the list of ‘Eighty-five Sail’ of transports sailing with Commodore Hotham. Eleventh on this list, carrying 206 Hessian soldiers of ‘Du Corps’, was Lord Sandwich, 368 tons, being commanded by a master called William Author.40 Just one Lord Sandwich features on Howe’s list, a fact that forges another link, proving that as Pfister was being tossed and jostled on his transport, not very far away was the old Endeavour.

Pfister was not alone in describing the Hessians’ Atlantic crossing. One of his fellow travellers was the poet and adventurer Johann Gottfried Seume, whose primary concern was the wretchedness of the food. ‘Today bacon and peas – peas and bacon tomorrow’, he commenced a philippic about conditions aboard. Only occasionally, Seume complained, would this monotony be interrupted by porridge, peeled barley or pudding ‘made of musty flour, half salt and half sweet water and of very ancient mutton suet’. The biscuits were riven with worms and so impenetrably hard they had to be split open with cannonballs:

We were told (and not without some probability of truth) that these biscuits were French, and that the English, during the Seven Years War had taken them from French ships. Since that time they had been stored in some magazine in Portsmouth and that they were now being used to feed the Germans who were to kill the French under Rochambeau and Lafayette in America.41

The Hessians had been loaded in the transports with such density they had felt like ‘salted herrings’ themselves. The bunks were intended to hold six men, ‘but after four had entered, the remaining two could only find room by pressing in’. The soldiers were obliged to lie straight as a flagstaff, and, ‘after having roasted and sweated sufficiently on one side, the man who had the place to the extreme right would call: round about turn! and all would simultaneously turn to the other side.’ Statistics suggest Seume wasn’t exaggerating. The 206 Hessians crammed aboard Lord Sandwich – which did not include the sailing contingent – was more than double the maximum Endeavour carried. Few could have prepared for such physical discomfort. As outsiders, Seume and Pfister were attentive to things sailors would consider too commonplace to mention. They write of glowing galley fires, steaming kettles, sodden clothing and bed linen and the ghastly cramped lower decks. Hanging like fruit bats at night and doubled up by day, the best place to be was up on deck, but this could be disquieting too. Climbing up on 20 May, Pfister saw a grey sky and felt a freshening wind. Despite the sailors’ protests that it was ‘simply good fresh air’, he noticed the galley fire being struck out, the sails being drawn in and the uppermost parts of the mast being fetched down.42

The dramatic centrepiece of Pfister’s account was what he rather grandly called the Whitsuntide Storm. He wrote of ships being scattered like leaves on the breeze. Inside his transport all is chaos. Everything ‘though tied fast’ is broken loose and catapulted ‘helterskelter’. The Hessians were sent flying too, ‘and there was no end to the spells of seasickness and of misery made ridiculous’. By 27 May:

The raging sea was playing with the gigantic structure of the ships as with a toy; sailors were swallowed up by the waters, others committed suicide and soldiers who ventured to go on deck fell down unconscious because of the force of the waves. Only one consolation remained, namely, the clarified atmosphere; but on the third day of Whitsuntide dark gloomy clouds and torrents of rain darkened the whole firmament, the winds seemed to be let loose, sounding like roaring thunder, all nature seemed to have united in bringing to young America a terrible funeral feast.43

So long seen through James Cook’s understated pen – he often described such storms as ‘blowing weather’ – Pfister depicts life at sea with melodrama fit for the stage. Such an attitude is understandable for someone unaccustomed to the sailors’ life and unfamiliar with the violence a collier could withstand – Cook had once written of Endeavour, ‘No Sea can hurt her laying Too under a Main Sail or Mizeon ballanc’d’ – but there is an additional distinction in attitude between the rational responses of the British sailor and those religious ones of the Hessian soldiers. ‘Stout Calvinists’, Pfister describes how they started ‘pleading’ for ‘the protection of heaven’, as if ‘a furious wrathful indignation rages in the American pulpit scattering its curses and, praying to God and Saviour, dedicated the fleet to destruction’.

With a loud and deafening roar the huge waves wash over the ships; the decks and every port-hole had to be made extra tight. The soldiers were lying in the lower compartments as if buried alive in coffins, gasping in the darkness after air and water; from moment to moment the most of them, quiet and depressed, expected to go out of this dark night into the eternal day of heaven.44

Pfister’s Whitsuntide Storm soon blew itself out, but it left Hotham with the devil of a job gathering up all the ships. Fifteen transports disappeared entirely. The destruction of the fleet by storm was one of the events Sandwich dreaded. It so nearly happened.

By the end of June 1776, ‘with many a change of wind and weather, of calm and turbulent sea, of joyous or anxious feeling’, Hotham had brought the fleet to the banks of Newfoundland. The plan had been to rendezvous with General Howe, but Howe was already gone. He had left behind an order for the fleet to meet him instead at the Sandy Hook lighthouse, off New York.

As the fleet turned south and Pfister watched ‘the sharp glow of Halifax lighthouse’ recede ‘like a star gradually fading away’, 500 miles away Ambrose Serle with Lord Howe on HMS Eagle was coasting past Long Island. ‘It appeared to rise into easy Hills, wch were every where clothed with Trees.’ On 12 July 1776, Serle woke to a brilliant sunlit morning and the ‘beautiful Prospect of the Coast of New Jersey’, with woods and houses plainly visible behind the white shingle of the shore.45

Howe’s flagship had experienced the same foul Atlantic weather. HMS Eagle had been ‘tossed from Billow to Billow, and sported about by the Winds & the Waves like a Feather’, terrifying Serle, leaving him fearing for the Hessian transports.46 Even when the storm had died away, violent gusts continued to buffet them. One day as Serle had walked on deck a sailor called William Englefield had fallen from the main-top, landing ‘within a few Feet’ of where Serle stood. His skull had been stove in on one side and ‘All the Booms, on wch he was dashed, were stained with Blood’, Serle wrote.47

As well as distressing sights there had been uplifting ones. Serle had been staggered by the icebergs they saw with one ‘at least as large as Westminster Abbey’.48 He had relished the entertainment of dolphins playing alongside as they came into soundings off the North American coast. ‘The Smell of the Land & of the Spruce-trees was very pleasant’, he wrote, ‘after so long Voyage, in which we had no better Effluvia than the Hold of a crouded Ship, or at best the Smell of Ropes & Tar.’49 Then there were the many flying fish, which Serle had read about. These fish were said to ‘fly against the Wind’ by the natural philosophers.50 This observation led Serle’s mind to the American rebels. He had thought long about the subject. His verdict was that the ‘rebels’ were scoundrels and ingrates. Like the flying fish they were launching themselves into the headwinds of history. ‘That the Turbulence and Malignity of a few factious Spirits should affect the Lives of Thousands’, Serle pondered, ‘and the Welfare of Tens of Thousands’, was a melancholy reflection indeed.51

On the afternoon of 12 July, the Eagle navigated the dangerous passage through Sandy Hook, and came to anchor off Staten Island.

Nothing could exceed the Joy, that appeared throughout the Fleet and Army upon our Arrival. We were saluted by all the Ships of War in the Harbour, by the Cheers of the Sailors all along the Ships, and by those of the Soldiers on the Shore. A finer Scene could not be exhibited, both of Country, Ships, and men, all heightened by one of the brightest Days that can be imagined.52

The Eagle was not long anchored before General Howe was aboard, acquainting his brother with the latest news. Admiral Howe had harboured hopes of defusing the conflict and before he had sailed from Portsmouth had secured for both him and his brother the power to act as peace commissioners. But that day Admiral Howe learned that the last chance for a negotiated settlement had recently passed. On 4 July the Continental Congress in Philadelphia had taken an irrevocable step and declared the colonies independent from Great Britain. No longer could the struggle be termed a quarrel or a rebellion. As John Adams put it, the colonies had entered into ‘the very midst of a Revolution, the most compleat, unexpected, and remarkable of any in the History of Nations’. For Serle, gazing across the bay to New York, this was proof of the ‘Villainy & the Madness of these deluded People’. The Eagle lay ‘in full View of New York, and of the Rebels’ Head Quarters’, Serle wrote. General Washington, he added, ‘is now made their Generalissimo with full Powers’.53

A short distance across the harbour, the mood in New York was tense but excitable. Receiving the news of independence on 8 July, Washington had ordered it to be read in public before his troops and the people of the city. After the reading, a mob had surged down Broadway towards Bowling Green, shouting huzzas and beating drums. The statue of George III erected to celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act was heaved down. The crowd hacked at the statue, mutilating its body. The king’s head was set on a spike outside a tavern while the remainder of the statue, so the story went, was carried away to Lichfield, Connecticut, where 4,000 pounds of lead were melted down ‘to be run up into Musquet balls for the use of the Yankees’.54

This jubilation was tempered by the appearance of the ships. On Saturday 29 June, General Howe’s fleet of a hundred sail had started to arrive from Halifax. Washington’s army had watched as they fell ‘into great confusion, all dropping upon one another’, as they tried to pass the treacherous sandbars at Sandy Hook. Perhaps now a strategic truth at last became apparent. New York was encircled by ‘deep navigable water’, but this was only accessible through two choke points: past these sandbars at Sandy Hook or through the notorious Hell Gate passage into the East River. Neither of these locations had been fortified. Now it was too late.

Watching Howe’s fleet arrive, one of Washington’s militiamen on Staten Island wrote, ‘I was upstairs in an outhouse and I spied as I peeped out the Bay something resembling a wood of pine trees trimmed … I declare at my noticing this, that I could not believe my eyes … I thought all London was afloat.’55 On 4 July, the New York Journal reported:

Last Saturday arrived at the Hook (like the swarm of Locusts, escaped from the bottomless pit) a fleet said to be 130 sail of ships and vessels from Halifax, having on board General Howe, &c. sent out by the Tyrants of Great Britain, after destroying the English constitution here, on the pious design of enslaving the British Colonies and plundering their property at pleasure, or murdering them at once, and taking possession of all, as Ahab did of Naboth’s vineyard.56

The Eagle and several other warships had since added to this number. Peering through his perspective glass, Serle surveyed New York on 12 July. ‘The Rebels appeared very numerous, & are supposed to be near 30,000; but from the Mode of raising them, no great matters are to be expected.’57

Among Pfister’s company of soldiers, morale had plummeted after the change of destinations from Halifax to Sandy Hook. To have suffered so long, only to find that they were to endure more, was sufficient to make them restless. The first object of their rage was General Howe, whom they blamed for changing plans. He had, Pfister wrote with asperity, ‘begun his career with blunders and perplexities’. Now he had started for Halifax ‘inopportunely’, then ‘changed his mind during the trip, and at last aimed for New York’. This additional leg would add at least a fortnight, Pfister foresaw, and possibly more to the length of the voyage, meaning that the Hessians would have spent nearly a hundred days at sea, ‘which was even at that time very rare’.58

To alleviate the threat of disease, a regime of constant cleaning had been put in place on the transports. The decks were scrubbed each day, fresh air was pumped beneath, bedding was aired on deck and the linens were disinfected in steaming vinegar. But nothing could be done about the dwindling supplies of rotting food. In the days after leaving Halifax, the first symptoms of scurvy began to show. Pfister put the malady down to ‘tainted humours’, and described how the Hessians sought to physic themselves with the chewing of tobacco, a habit learned from watching the English sailors, and also by swigging sea water. It was all to no avail. ‘The disease reigned supreme’, Pfister wrote. Made thirsty by the salty water and sweating in the growing summer heat, the soldiers were horrified to find that the water ‘which in the whole fleet had been stored in oaken casks’ was growing ‘undrinkable and finally putrid’.

Entering his third month at sea, Pfister’s account grows woozy and elegiac. He gazed, awestruck, at ‘the threatening, gigantic cone of a water spout’, as it whipped up the waters around one of the transports. The air grew thick. St Elmo’s Fire – the sign of a highly charged atmosphere – shone at the tops of masts and on the yardarms. Pfister saw the glow, ‘feared as an apparition of a warning spirit’. On 12 July the weather broke spectacularly, ‘in a most fearful thunder storm’. The following morning a strong wind ‘tore to pieces the sails on several ships’ but it also dispersed the black clouds. A calm succeeded. Across the stillness of the fleet, Pfister heard the singing of hymns. It was a Sunday, he realised. As the services finished, a dense sea fog enveloped the transports and rain began to fall. ‘All at once there was a great outcry in the fleet’, Pfister wrote.

Two ships, the Hartley (with Knyphausen soldiers under Captain von Biesenrod) and Lord Sandwich (on board of which was Colonel von Wurmb and a part of the life guards) could be seen colliding because of the great waves, causing each other considerable damage.59

Watching in alarm as the two transports crunched against each other, Pfister could not have known that he was committing to history the last direct eyewitness account of Lord Sandwich at sea.

The scene disturbed Pfister and more was to come. Made furious by their mistreatment, the discipline of those on board began to suffer. A duel was fought on one ship. On another the sailors mutinied and had to be arrested before the cutlasses and pistols could be served out. This, at least, was an aberration. Pfister was heartened by the industry of the sailors he saw. From the damp fogs to the storms and into the blazing heat of summer, their toil was unremitting. Pfister marvelled at their ‘ever agility’, as they sprang from the shrouds and hared up and down the ratlines. ‘As a spider that moves about as swiftly as the arrow in her web’, he wrote, ‘so the sailors were going up and down the rope ladder of the masts and through the rigging, hanging only at their feet, tying the tackle and binding the sails.’

Three weeks of wanton and fretful weather followed, until on 10 August, the transports’ sails were filled by ‘a most speedy wind’. With ‘high towering sails’ they at last made good time, splitting the waves and currents off New England. By 11 August the ‘charming coast of Long Island’ was before them. The next morning the English flag was unfurled across the fleet, and Sandy Hook – that long-wished-for rendezvous – rose out of the western horizon, with its white lighthouse. Staten Island lay behind.

A veritable painting spread itself out before the eyes of these newcomers, most charming after so many dangers had been encountered and after so long a denial of a glance on the beautiful smiling landscapes, teeming with inhabitants, exalted and majestic, the shores studded with troops, the tents of a friendly and a hostile camp, of a forest of masts of 500 ships, and the many hundred boats which so vigilantly were watching the hostile shores—here a belligerent power assembled, such as America had never seen before in order to have a combat, which in the destiny of the world gave its immeasurable decision.60

Serle watched the transport fleet anchor off Staten Island on 12 August 1776. ‘We were gladdened with the Sight of the grand Fleet in the offing’, he scribbled. ‘The Joy of the Navy & Army was almost like that of a Victory.’ One by one the colliers navigated the sandbars at Sandy Hook. So great was the mass of ships, and so long the queue they formed, that it took the entire day for the whole fleet to cross the bar. ‘So large a Fleet made a fine Appearance on entering the Harbour’, Serle wrote, ‘with the Sails crouded, Colours flying, Guns saluting, and the Soldiers both in the Ships and on the Shore continually shouting. The Rebels (as we perceived by the Glasses) flocked out of their lurking Holes to see a Picture, by no means agreeable to them.’

Running his glass over the collier fleet, Washington and his military commanders in New York could only reflect that this was the worst they could ever have expected. Britain had thrown all of their forces against the one place he had resolved to defend. In New York harbour there was now amassed the most powerful naval force that Britain – or England before her – had ever sent into combat. In fact Sandwich’s 1776 fleet remained the greatest land and sea force assembled by Great Britain until the D-Day landings in World War Two.

Gazing timorously across the bay from lower Manhattan, Joseph Reed, the lawyer turned revolutionary, wrote home to his wife, ‘When I look down and see the prodigious fleet they have collected, the preparations they have made, and consider the vast expenses incurred, I cannot help being astonished that a people should come 3,000 miles at such risk, trouble and expense, to rob, plunder and destroy another people because they will not lay their lives and fortunes at their feet.’61

When sailing in the Pacific as Endeavour, the ship had emitted a mystic air. Often her power came from her strangeness, her unknown capacities or from incomplete understandings of her technology. By contrast, in New York people were all too aware of the significance of these transports. As they watched the Hessians disembark with their equipment and munitions, everyone understood what was to come. The potency of this fleet has long been acknowledged. Endeavour’s presence within it never really has. The bark had seen so many vistas, from the coal staithes on the Tyne, the glinting waters in Matavai Bay, the Deptford Yard, Batavia Roads and the remote colonial outpost at Port Egmont. But no scene was a theatre quite like this. ‘We expect to be attacked every tide’, confessed one New Yorker on 12 August.

‘We have now a gallant Fleet here’, Serle wrote two days after Lord Sandwich’s arrival.62 ‘Besides Sloops, Bombs, Fireships, armed Vessels, &c. The whole Fleet consists of about 350 Sail. Such a Fleet was never seen together in America before; wch is allowed on all Hands.’ That night a great formal dinner was held on the Eagle. In attendance was a list of names that would pass into history. There was Admiral Howe, his brother General Howe, Lord Cornwallis, General Grant, Sir Peter Parker and the Hessian commander General Heister. ‘Our Army now consists of about 24,000 men’, Serle confirmed, ‘in a most remarkable State of good Health & in high Spirits. On the other Hand, the Rebels are sickly & die very fast.’63

Five days after Lord Sandwich’s arrival, on 17 August 1776, Washington issued a proclamation:

WHEREAS a Bombardment and Attack upon the City of New-York, by our cruel, and inveterate Enemy, may be hourly expected: And as there are great Numbers of Women, Children, and Infirm Persons, yet remaining in the City, whose Continuance will rather be prejudicial than advantageous to the Army, and their Persons exposed to great Danger and Hazard: I Do therefore recommend it to all such Persons, as they value their own Safety and Preservation, to remove with all Expedition, out of the said Town, at this critical Period, trusting, that with the Blessing of Heaven upon the American Arms, they may soon return to it in perfect Security.64

Events now happened apace. On 25 August Serle watched the ‘main Body of the Hessians’ cross the channel to Long Island.65 Two days later Washington’s army was routed at what became known as the Battle of Brooklyn, the biggest battle of the revolutionary war. On 15 September General Howe invaded Manhattan Island at the Battle of Kips Bay and New York fell to the British. On 16 November a Hessian-led attack stormed Fort Washington at the north of Manhattan. Almost 3,000 troops of the Continental Army were captured and those remaining were forced to retreat into the Jerseys. Although General Howe failed to completely destroy his army, for Washington it was the most desperate moment of the entire war. General Hugh, Lord Percy, writing to Lord George Germain, summarised: ‘this business is pretty near over’.66

Serle was equally expectant. ‘All Philadelphia, we heard this morning, is in Confusion from the Expectation of a Visit; and many of the Inhabitants are moving out of Town with their Effects’, he wrote on 22 November.67

Serle realised that Howe had other targets in mind too. On 28 November, he watched as ‘Most of the lighter Transports laden with Troops passed up the East River, in order to go through Hell-Gate into Connecticut Sound’, to begin their next operation.68 A month later in London, on 30 December, the king sat down to compose a congratulatory letter. 1776 had gone as well as he could have hoped. ‘Lord Sandwich’, he began, ‘The accounts from the Admiral and General are the more agreable as they exceed the most sanguine expectations.’ With a new year beckoning, the king anticipated more good news. ‘The possession of Rhode Island cannot fail of success.’69