I was eleven when my mother sent me to boarding school in Salisbury. Yes, granted, she did have tears in her eyes as she brought me to the station. But she still put me on that train.

“Your father would have been so happy about you going to his old school!” she said, forcing a smile onto her lips. And The Beard gave me such an encouraging slap on the shoulder that I nearly shoved him onto the rails for it.

The Beard. The first time my mother brought him home, my sisters immediately crawled onto his lap. I, however, declared war on him as soon as he put his arm around Mum’s shoulder. My father had died when I was four, and of course I missed him, even if I barely remembered him. But that definitely did not mean I wanted a new father, especially not one in the shape of an unshaven dentist. I was the man around the house, uncontested hero to my sisters and apple of my mother’s eye. Suddenly she no longer watched television with me in the evenings but instead went out with The Beard. Our dog, who would chase anyone off our grounds, put squeaky toys in front of The Beard’s feet, and my sisters drew oversize hearts for him. “But he’s so nice, Jon!” I heard over and over. Nice. And what exactly was so nice about him? That he convinced my mother everything I liked to eat was bad for me? Or that he told her I watched too much TV?

I tried every trick in the book to get rid of him. At least a dozen times I disappeared the house keys Mum had given him. I poured Coke over his dentistry magazines (yes, there are magazines for dentists). I mixed itching powder in his beloved mouthwash. All useless. In the end it wasn’t him but me whom Mum put on the train. Never underestimate your enemies! Longspee would teach me that later. But I hadn’t met him yet.

My banishment had probably been decided after I convinced my youngest sister to pour her oatmeal into his shoes. Or maybe it was the WANTED TERRORIST poster into which I’d Photoshopped his picture. Whatever it was, I’d bet my game console that the boarding school was The Beard’s idea, even though my mother denies it to this day.

Of course Mum offered to deliver me personally to my new school and to stay for a few days in Salisbury “until you find your feet.” But I refused. I was positive she just wanted to soothe her guilty conscience because she was planning to go on to Spain with The Beard while I, on my own, would have to deal with totally new teachers, bad boarding-school food, and new classmates, most of whom were probably going to be stronger and way smarter than me. I’d never spent more than a weekend away from my family. I didn’t like sleeping in strange beds, and I definitely didn’t want to go to school in a town that was more than a thousand years old—and even proud of it. My eight-year-old sister would have loved to swap with me. She’d been reading Harry Potter, and she was desperate to go to a boarding school. I, however, had nightmares of children in hideous uniforms, sitting in dingy halls in front of bowls filled with watery porridge, watched by teachers with yardsticks.

I didn’t speak a word all the way to the station. I didn’t even give my mother a kiss good-bye after she had hoisted my suitcase onto the train. I was too afraid I’d collapse into a sobbing, childish mess in front of The Beard. I spent the entire train ride cutting and gluing ransom notes from old newspapers, threatening The Beard with all manner of terrible, painful deaths if he didn’t leave my mother immediately. The old man sitting next to me kept looking over with increasing alarm, but in the end I threw the letters away in the train’s lavatory. I told myself that my mother would probably figure out who’d composed those letters and that she would just end up preferring The Beard over me even more.

I know. I was in a pathetic state. The train ride lasted for one hour and nine minutes. That’s now more than eight years ago, and I still remember it perfectly. Bristol—Bath—Westbury. The train stations all looked the same, and with every passing mile I felt more banished. After half an hour I had devoured all the chocolate bars Mum had packed for me (nine, as I remember—she’d felt really guilty!). Every time I looked out the window and everything started looking blurry, I told myself it wasn’t tears but the rain running down the windowpane that distorted my vision.

As I said, pathetic.

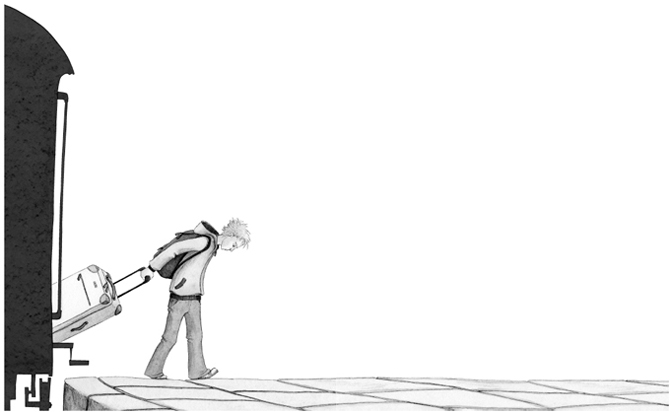

While I was dragging my suitcase out of the train in Salisbury, I felt terribly young and at the same time aged by a hundred years. Banished. Homeless. Mother-, dog-, and sisterless. A curse on The Beard! I dropped the suitcase on my foot, sending a prayer to hell, begging for some contagious disease that affected only dentists vacationing in Spain.

Anger felt much better than self-pity. Also, it was useful armor against all the curious looks.

“Jon Whitcroft?”

In contrast to The Beard, the man who was taking the suitcase out of my hand and shaking my chocolate-covered fingers didn’t have even the shadow of a beard. Edward Popplewell’s round face was as hairless as mine (and caused him much distress, as I was soon to find out). His wife’s upper lip, however, was sprouting a dark mustache. Alma Popplewell’s voice was also deeper than her husband’s.

“Welcome to Salisbury, Jon!” she said, suppressing a little shudder as she pressed a handkerchief into my sticky fingers. “You can call me Alma, and this is Edward. We are the house wardens. Your mother told you we’d be picking you up, didn’t she?”

She smelled so intensely of lavender soap that I nearly gagged—or maybe it was the chocolate bars. Wardens… great! I wanted my old life back: my dog, my mother, my sisters (though I could have done without them), and my friends at my old school… no Beard, no beardless warden, and no lavender-soapy housemother.

The Popplewells were, of course, used to homesick newbies. As we left the station, Edward the Beardless placed his hand firmly on my shoulder, as if wanting to squash any thoughts of escape. The Popplewells didn’t drive. (There were some nasty rumors that this was due to Edward’s great love of whiskey and his firm belief that its regular consumption might yet sprout some stubble on his baby-smooth cheeks.) Whatever the reason, we went on foot, and Edward began to tell me as many facts about Salisbury as could be crammed into a thirty-minute walk. Alma interrupted her husband only when he mentioned dates, for those he confused quite often. But she might as well not have bothered. I wasn’t really listening anyway.

Salisbury. Founded in the damp mists of prehistory. Fifty thousand inhabitants and more than three million tourists who come every year to stare at its cathedral. The town welcomed me with pouring rain. The cathedral stuck its tower out from among the wet roofs of the city like a warning finger. Hear ye, Jon Whitcroft and all sons of his world. Thou art fools for believing your mothers love you more than anyone else.

I looked neither left nor right as we walked down a street that had already been there when the Black Death had last come through town. Somewhere along the way Edward Popplewell bought me an ice cream (“Ice cream tastes nice even in the rain, am I right, Jon?”), but in my world-weariness I didn’t even manage to squeeze out a “thank you.” Instead, I imagined spreading chocolate stains over his pale gray tie.

It was late September, and despite the rain the streets were packed with tourists. The restaurants were all offering fish-and-chips specials, and the window of a chocolate shop actually did look quite alluring, but the Popplewells steered straight toward the gate in the old city wall, which is flanked by little shops, all offering cathedrals, knights, and water-spitting demons cast in silvery plastic. It was the vista beyond the gate that had all the strangers with their garish backpacks and packed lunches filing down Main Street. I didn’t even lift my head as the Cathedral Close opened up in front of me. I didn’t give a glance to the cathedral and its rain-darkened tower, nor to the old houses that surround it like a clutch of well-dressed servants. All I saw was The Beard, sitting on our couch in front of our television, my mother to his right, my sisters to his left, fighting over who got to climb into his lap first, and Larry, the treacherous dog, rolled up by his feet. While the Popplewells were exchanging words above my head, arguing over the exact year in which the cathedral had been completed, I saw my deserted room and my deserted chair in my old classroom. Not that I’d ever particularly enjoyed sitting on it, but suddenly the thought of it nearly brought me to tears—which I quickly wiped away with Alma’s lavender-reeking (and now chocolate-brown) handkerchief.