OH, BEAUTIFUL?

by René Pedraza del Prado

THE SON OF TWO CUBAN EXILES EXPERIENCES THE UGLINESS OF PREJUDICE IN AMERICA.

I was born in the United States, the son of two Cuban exiles who reluctantly abandoned their homeland, exiles from an oppressive dictator and the disillusionment of the false emancipator and traitor to the principles of freedom and justice that followed. They were young idealists seeking a refuge, an oasis from the mendacity and corruption that have plagued Cuba for centuries. Like all of America’s orphaned children, they came upon her promising shores with faith and hope in the higher moral ground and opportunity they held.

I was a child of the sixties. My father always sang the praises of our adoptive country and every day gave thanks in prayer at our dinner table to have his family safe and sound in the greatest country in the world, a country of freedom, principles, morality, a country where a decent, honest man could accomplish literally anything. At home we spoke Spanish, but once out the door, I was forbidden to speak anything but English.

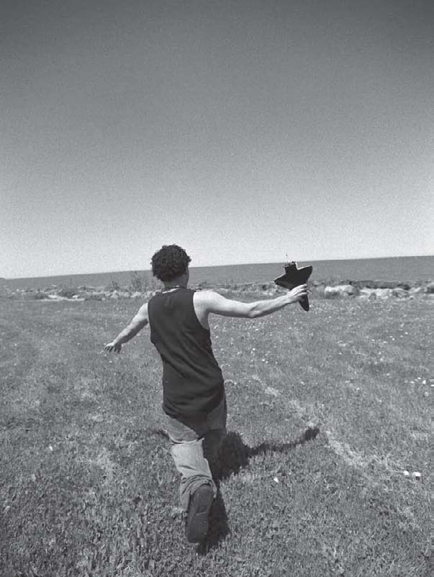

In 1969, when the Apollo astronauts landed on the moon, he shook me awake in tears and said, “Look, René, see, here anything is possible.” In my starry-eyed, eight-year-old, somnambulant state, I stared, incredulous at the black-and-white images, in awe and admiration as Neil Armstrong heralded one giant leap for mankind. The moment is etched in my mind as surely as a diamond engraves a stone. For my tender years I well understood the majesty of the moment. For months afterward I drew endless sketches of rocket ships, planets, stars. I would sway upon a swing in our backyard at twilight and, looking up at heaven, revealing her jewels one by one, sing “God Bless America” over and over, in such pride and true love for my country; to this day it is my favorite patriotic hymn. One day I, too, would reach them. Some way I, too, would touch the sky.

Back at school in my third-grade classroom, when my teacher asked the assembled children what we aspired to become when we grew up, I responded self-assuredly, still imbued with my astral passion, “An astronaut or an actor or a magician!” She looked back at me with barely veiled derision and scornfully replied, “I’m so sorry to hear that, René, because your people, Cuban people, are marked to be janitors or garbage collectors.” Another time, when I was distractedly singing a song to myself in class, lost in my childhood reveries, she marched to my desk and asked that I put my hands out before me. Trusting her (for I loved her in spite of herself), I did just that; she then violently struck a ruler across my knuckles and said, “Next time you’ll learn to be quiet in class and begin to become a good citizen.” I walked home alone, crying the distance, feeling, feeling. I have never forgotten, forgiven.

This was my first bitter taste of the humiliation and degradation that is too often the foul fruit of prejudice and ignorance, a fruit I would come to taste too often in our beloved America the Beautiful, America the Free, America the Equal, with liberty, justice for all.

My father also learned this rancid truth, and yet he never lost his childlike passion and admiration for the people of this great country, even as he discovered that he was not destined as one of these great and powerful titans. He erroneously felt that it was he who had fallen short of the mark, he who was lacking and found wanting. He kept us in good middle-class comforts, and even luxuries, but little by little his sense of self and identity was chiseled and fragmented and crumbled in small but irrevocable ways; such is the fate of the exile, transplanted from his natural state, domain, province. As I grew up, I witnessed this once proud and genially charming man begin to bend his shoulders, saw his dazzling smile become progressively a sad and lamentable frown.

I am glad he died before the rot of this fruit, like a metastasized cancer, spread like a wildfire of greed and corruption, distortion and degradation, that has made our modern-day nation unrecognizable from the leading force of human rights and dignity it once had the moral right to impeach the entire world with.

Had he lived long enough, he might have realized that, but for the glories of material abundance, his cherished beacon had dimmed to a dull and feeble shadow of its past and true greatness and had begun to look more and more like the same beast he’d fled from all those years ago.

Could he have borne the criminal, vulgar, and terrifying decimation of all he dearly held to be the highest of human values, the decent tenets of a civilized world now run afoul by a thirst for power and conquest at any price over the eternal verities of morality and common decency?

I think not; but it doesn’t matter anyway, for he died of a broken heart just in time, before this unyielding, unrelenting monster reared its ugly head: unabashed, unashamed, unrepentant, unmoved, unprincipled, and un-American.

As for my heart, it beats on, fighting against all the terrible evidence, hoping to leave a mark, a glimmer of hope, of beauty, of love…for the sake of all those little unborn astronauts, actors, and magicians of the world to come, that they might perhaps have something of better value to hold in their future hands besides a mere dollar bill to reckon their self-worth with. I yet still love my country.