Ever since we figured out fire, stone tools, language, and the other great innovations of early humankind, change has been upon us. That’s why they call it evolution. That the rate of change today is arguably faster than it has ever been before is probably true. Cultural theorist Paul Virilio refers to that rate—and our pursuit of a science and logic of speed—as dromology, from the Greek dromos, meaning “to race.” For him, the speed at which change is occurring is as much about a dramatic shrinkage in space as it is of time. As our technology, transportation, communication, and other ways of being in the world become increasingly fast and efficient, the old traditions around which cultures, economies, and politics have been organized are upended.

One result of that speed is disruption. And few, if any, of the old traditions have been more disrupted in recent years than big business. In response to constant cultural turbulence and its effect on their reputation, growth, and bottom line, some large companies have turned to design thinking as a way to help them make sense of disruption and sustain competitiveness.

The sources of disruption are many, but one is obvious. As technological innovation accelerates, people, communities, organizations, and objects are more interconnected than ever before. Thanks to everything Internet, our world has shrunk and we are now very close. As a result, we talk more, share more, complain more, celebrate more, ideate more, and expect more.

This disruption has not been kind to businesses used to operating by the rules of the old model. We don’t have to watch their TV ads anymore. We don’t believe their marketing hype anymore. We don’t want to eat their junk ingredients anymore. We don’t have to buy from stores anymore. And we don’t want the best of them to just be profit machines anymore. We want more, when we want it, how we want it, and at the price we want.

It is a vibrant and definite sea change from the way business was always done, when financial profit was a driving force. Today, people are not afraid to say, Screw business as usual!—and show they mean it.

—Richard Branson

For businesses that have been most affected by recent disruptions in technology and social communication, the challenge is one of management. Originally, management was designed for a very different set of business needs: ensuring that repetitive tasks were completed, improving economic efficiency, and maximizing labor and machine productivity. Today those needs are vastly different. Why? Because we’re facing a crisis. Actually, we’re facing many crises. There are crises of competition, economy, disruptive technology, job creation, social development, and sustainability. Some are more pressing than others. The natural resources crisis is certainly more pressing than the economic crisis, and it’s getting worse as populations and their level of consumption keep growing faster than human and technological innovation can find ways of expanding what can be extracted from or produced in the natural world.

But there is also a crisis of trust and credibility. The management solutions that many leaders apply in case of emergency no longer cut it. With most overwhelmed by the complexity and scale of the problems that confront them, the true risk exposure of any organization is very difficult to assess. As a result, proven management tools and techniques are being questioned for their validity and effectiveness. Most were designed for a very different world and operate based on organizational designs well beyond their best-before date, like those pointless mission statements that are supposed to align employees. If you’ve ever wondered where such inspirational tomes originated from and what we’re supposed to do with them, now might be the time to hang them on a wall and call them antiques. Or just have a laugh with Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams, who defined a mission statement as “a long, awkward sentence that demonstrates management’s inability to think properly.”

We need a new way, one that’s smart, human, cultural, social, and agile and that puts innovation at the core of every move it makes. That way could be design thinking. They won’t teach you this at B-school or D-school, largely because these organizations suffer from the same strain of anticomplexity that haunts many big businesses. And that’s what this book is all about.

We want more, when we want it, how we want it, and the price we want.

We agree that our world is changing rapidly. The future is not like the past. The way we do business today will not be the way we do it in the future. And it’s as difficult to predict the weather over the next 12 months as to predict the performance of a business.

Of course, we know that we can’t really predict the weather. Meteorologists predict changes in weather patterns by studying atmospheric patterns, compiling data, and applying what they see to predict what they think will occur. But their record of accuracy is poor beyond the short term, largely because they are relying on the present to imagine the future. In the 1960s MIT professor, mathematician, and meteorologist Edward Lorenz formulated a model of the way air moves around the atmosphere, measuring changes in temperature, pressure, and velocity. Stripping the weather down to 12 differential equations, working through reams of printed numbers, and plotting simple charts, he discovered that slight differences in one variable could have a profound impact on the outcome of an entire system. By modeling weather, Lorenz discovered not only the fundamental mechanism of deterministic chaos—sensitive dependence on initial conditions or the “butterfly effect”—but also that long-term weather forecasting was impossible.

Similarly, much of what we do in business strategy and planning is an attempt to predict the future based on the present and the past. Despite pouring millions of dollars into enterprise resource planning systems, however, we can only project three to six months into the future at best with any reasonable accuracy. Why? Because most business leaders are averse to chaos, are overly linear, and are disconnected from global ripples not directly related to the world of business.

We are all more connected than we know. Whether it’s business or any other systems-level organizational challenge, design thinking helps us appreciate and make sense of the complex connections between people, places, objects, events, and ideas. This is the most powerful driver of innovation. It’s what guides long-range strategic planning. It’s what shapes business decisions that have to be based on future opportunities rather than past events. It’s what sparks the imagination. And it’s what reveals true value.

Innovation management is about more than just planning new products, services, brand extensions, technological inventions, or novelties. It’s about imagining, organizing, mobilizing, and competing in new ways. To do that with any degree of success, organizations should heed the words of American countercultural poet Tuli Kupferberg: “When patterns are broken, new worlds emerge.”

If you think strategic planning powers strategic innovation, you’re living in the old world. Design thinking powers strategic innovation. It can be used to begin at the beginning of an idea or used to unlock hidden value in existing products, services, technologies, and assets—thereby reinvigorating a business without necessarily reinventing it. A disciplined process that can result in significant economic value creation, meaningful differentiation, and improved customer experience, design thinking is by nature unorthodox. But it also holds the core capabilities behind innovation.

Sometimes we make our worst decisions when we’re in the middle of a crisis. By acting reactively rather than proactively or defensively rather than offensively, we rely on how we have managed issues in the past—usually by isolating one or more discrete factors as the cause of the crisis and then attacking them. Whether it’s applied in a tactical or strategic fashion, design thinking can help us get out of the crisis mode by considering challenges from a systems level.

The de facto design of management is not designed to ask managers to be creative but to deter managers from doing the wrong thing or taking extra risks.

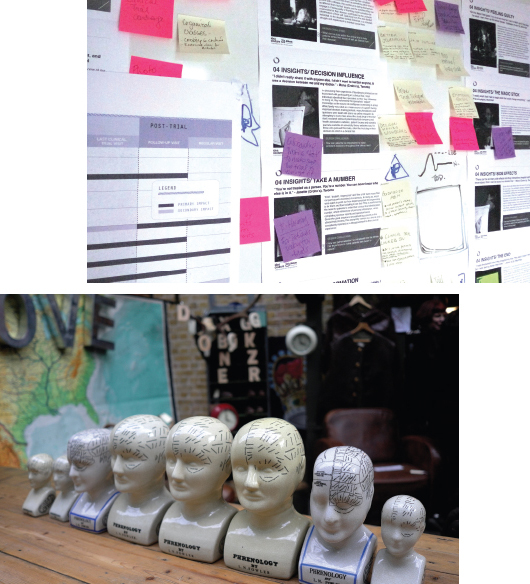

Today, many businesses have been battered by systems-level economic failure and the collapse of traditional organizational design and management processes. These failures have left some business leaders gazing hopefully toward design thinking as the next management “wonder drug.” Given how various authors have presented it as a way to address complex, ambiguous, uncertain, and volatile circumstances across multiple contexts and cultures, design thinking is often touted as bringing a refreshed, revitalized, and rejuvenated approach to management and strategic thinking. It does, but it is far from a magical cure-all. Just as the pioneers of the modernist movement recognized the need for new design concepts to match the technological advancements of the twentieth century, we need to recognize the need for new management concepts to match the disruptive era of the twenty-first century.

It has been a heady decade for design thinking. Will it fall out of favor over the next few years, like other short-lived management fads? Or will it forever change the way business is done? Only time will tell. Traditional design firms, branding agencies, and design studios are all quick to claim that they can change their clients’ worlds; however, their clients might be disappointed with such a promise if their consultant partners lack an understanding of business strategy, portfolio management, market power, industry dynamics, channel economics, and capital intensity. Change requires more than just cool design and catchy slogans. Adding a few young MBAs to your staff does not turn you into a strategy consultancy firm. And brushing on a thin veneer of design thinking won’t do you much better. Design Thinking is changing the paradigm of management and it will impact us for decades.

The problem with the rat race is that even if you win, you’re still a rat.

—Lily Tomlin

The de facto design of management is not designed to ask managers to be creative, but to deter managers doing the wrong things or taking extra risks.

| 20th Century | 21st Century |

| Scale and Scope | Speed and Fluidity |

| Predictability | Agility |

| Rigid Organization Boundaries | Fluid Organization Boundaries |

| Command and Control | Creative Empowerment |

| Reactive and Risk Averse | Intrapreneur |

| Strategic Intent | Profit and Purpose |

| Competitive Advantage | Comparative Advantage |

| Data and Analytics | Synthesizing Big Data |