Ask a bunch of people who subscribe to design thinking exactly what it is, and you will get a bunch of answers, each of which varies just enough from the last one to give you the answer you’re looking for: There is no single, unifying, common definition of design thinking. Given its predilection for dealing with ambiguity, perhaps there shouldn’t be.

For most practitioners, the idea of design as a way of thinking can be traced backed to Herbert Simon and his 1969 book, The Sciences of the Artificial. An American political scientist, economist, sociologist, psychologist, and professor at Carnegie Mellon University, his distinction between critical thinking as an analytic process of “breaking down” ideas and a design-centric mode of thinking as a process of “building up” ideas is foundational to the practice. So, too, is his definition of design as “the transformation of existing conditions into preferred ones.”

From Robert McKim’s 1973 book Experiences in Visual Thinking to Peter Rowe’s first noteworthy use of the term in 1987’s Design Thinking to Richard Buchanan’s highly influential article “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking,” Simon’s big idea—that design is always linked to an improved future—has continued to shape the practice in every direction.

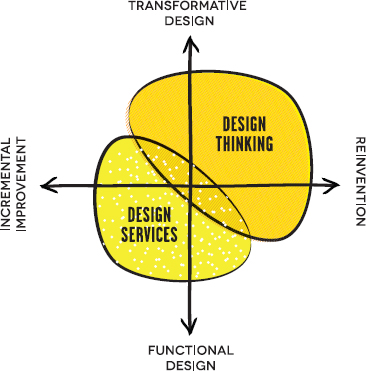

More recently, design thinking has caught the attention of businesspeople, thanks to it finding its way into the pages of publications like Bloomberg Businessweek and Harvard Business Review. Where Simon and those who followed him took a more considered, scholarly approach to the epistemological underpinnings of the practice, the understanding of design thinking in the business press is overly simplistic. In focusing on applying a human-centric approach to identifying problems followed by a rapid prototyping of ideas into tangible artifacts or nonfunctional models to solve those problems, the business press tends to do to design thinking what it does to most complex issues: turn it into an easily accessed tool kit that anyone can use.

A design thinking organization is capable of effectively advancing knowledge from mystery to heuristic to algorithm, gaining a cost advantage over its competitors along the way.

Typically characterized as a step-by-step process that’s made sexy with the help of multicolored Post-it Notes, mind maps, and other overly simplistic visual representations of complex systems or experiences, the business press has romanticized design thinking as a way to solve problems and drive profit. It’s most simplistic definition? Design thinking is a way to get businesspeople to think like designers and designers to think like businesspeople. But design thinking is more than that.

And with that cost advantage, it can redirect its design thinking capacity to solve the next important mystery and advance still further ahead of its competitors.

—Roger Martin

So, what is Design Thinking?

The answer to all is, “Yes, and more!” Here is my definition of design thinking: Design thinking is the search for a magical balance between business and art, structure and chaos, intuition and logic, concept and execution, playfulness and formality, and control and empowerment.

In my practice, this is a framework for a human-centered approach to strategic innovation and a new management paradigm for value creation in a world of radically changing networks and disruptive technology. Although that framework is certainly populated by valuable processes or tools (which we’ll get to later), it is the framework itself that is where the magical balance resides. Design thinking is about cognitive flexibility, the ability to adapt the process to the challenges. And when it comes to organizations that successfully apply design thinking to challenges, that framework is essentially cultural. If you were to try to describe the culture of a design thinking organization, some of the words that would likely arise might include:

How many big organizations have cultures that are like this? The answer is very few, which is why innovation is so challenging without the help of other, usually smaller, organizations that do have such cultures. Respected design critic and educator Don Norman suggests that one of the major problems related to innovation is the ability to manage the desirable, feasible, and economically viable. Although he is referring to designing things, the problem is equally present when designing systems, services, or even cultures.

Design thinking is not an experiment; it empowers and encourages us to experiment.

We don’t usually associate design with science, but many design theories have been inspired by scientific disciplines, particularly the natural sciences. In such cases, design is envisioned as an objective, rational procedure that draws on the same rigorous standards of testing and verification as the sciences. These theories focus on problem framing and problem solving.

In the world of business, problems (starting point) and goals (end point) are said to be like a chess game: The initial positions of the pieces are clearly defined and the goal, of course, is to checkmate and win the game. But in design that’s not the case. As Donald Schön writes in The Reflective Practitioner, “In real-world practice, problems do not present themselves to practitioners as givens. They must be constructed from the materials of problematic situations which are puzzling, troubling, and uncertain.”

That’s why design theorist and educator Horst Rittel called design problems “wicked” and proposed that we need a completely different approach, what he called a second generation of design theories and methods. He advocates that if the first generation was aiming to make design a purely rational process, the second generation recognizes that the notion of rationality implies serious paradoxes and that distinctions between systematic versus intuitive and rational versus nonrational design are untenable.

Some of the principles of design thinking originated from design discipline but were adapted to apply in a wider and more complicated business context. Design thinking is popular among educators and social entrepreneurs for social innovation because it approaches problem solving from the point of view of the end user and calls for creative solutions by developing a deep understanding of unmet needs within the context and constraints of a particular situation. Some designers are picking up the skills when working in close collaboration with other domain specialists in the field of engineering, economics, and social sciences. It has yet to find its way into business schools so that our next generation of managers can be better equipped to handle increasingly complex challenges.

Language that used to be associated with designers has now entered other fields: Hospital administrators are told they should be more patient-centric, policy makers are told that public services should be more user-centric, and businesses engage with customers by offering new meanings for objects. Design thinking is not something that is taught and practiced in a studio anymore. For executives and managers it is becoming our everyday language.

Design thinking’s association with or application in business is often way oversimplified. It is more than just Post-it Notes covering a wall or creative ways to brainstorm ideas. And it is more than a five-, six-, or seven-step process to arrive at those ideas. Such an oversimplification forces us into predetermined roles, and with those roles come rules, conventions, behaviors, and formal expectations that will ultimately restrict what it is we think and do.

“Complexity is the prodigy of the world. Simplicity is the sensation of the universe. Behind complexity, there is always simplicity to be revealed. Inside simplicity, there is always complexity to be discovered.”

—Gang Yu

It is important to recognize that Design Thinking is not exclusive to designers, or unattainable to those in other disciplines. Design Thinking is natural and inherent in all of us. It is an approach to inquiry and expression that complements and enhances existing skills, behaviors, and techniques. But it’s also critical not to define the discipline as the antithesis of data-driven analytical thinking. Design Thinking is its own mode of analysis—one that focuses on forms, relationships, behavior, and real human interactions and emotions.

These may include: