Private Nick Pilozzi gasped.

Oh my God, I can’t breathe, he thought.

It was April 2006, and Pilozzi and others from 3-71 Cav’s Able Troop, led by Captain Gooding, had been choppered in and dropped atop a twelve-thousand-foot snow-capped mountain on the southern slope of the Hindu Kush for Operation Mountain Lion. The air was so thin he felt as if he were being slowly, almost subtly, strangled.

Pilozzi, who was eighteen, came from Tonawanda, New York, not far from Buffalo, so he knew from cold. But there was something devastating about the combination of the deep snow, the chill, and the lack of oxygen to be found here on the roof of these mountains. His driving skills were not needed up here; there were no cars or trucks. There wasn’t anything except for rocks and snow—anywhere from two to six feet of it. Most of the snow was packed, so the troops were able to walk on it, but they exhausted themselves digging down to rock to position their mortar tube—the cannon from which they would aim and fire explosive rounds—lest the weapon sink into the powder.

The Americans had had no idea it was going to be so cold—just one more indication that they didn’t know much about the land they were supposed to be controlling. The troops hadn’t packed appropriate cold-weather gear and had just fifteen sleeping bags for thirty men, including the handful of Marines who had joined them. They ended up dividing the bags—some got the Gore-Tex outer layer, others the thick black inner layer—and laying them atop the rock formations that jutted out of the snow. Troops clung to one another for body heat. Everyone survived, but it was the roughest night many of them had ever known. And that was how Private Pilozzi met the Korangal Valley.

(Photo courtesy of Nick Pilozzi)

The Korangal Valley was tough to get into and even tougher to get out of. The region was home to roughly twenty-five thousand Afghans, an insular community with its own particular dialect. Some Korangalis trafficked in illegal timber, selling lumber from the Himalayan cedars that grew in the valley; such traffickers were sufficiently ruthless that their influence far exceeded their numbers. The combination of this criminal culture with its geographic, cultural, and linguistic isolation had made the Korangal an inviting sanctuary for insurgents fighting the USSR in the 1980s, and then later again for those fighting the United States in the 2000s. (The Korangal was close to where those nineteen SEALs and Nightstalker pilots and crewmen had been killed in 2005, during Operation Redwing.)

Now 3-71 Cav had been diverted to the region because Colonel Nicholson wanted to take advantage of the temporary overlap, in Kunar Province, of 3-71 Cav (commanded by Fenty), 1-32 Infantry (led by Cavoli), and the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, which was scheduled to leave the country in late May.

Nicholson, who commanded the parent brigade, ordered 3-71 Cav to flank around the valley to the east while 1-32 Infantry blocked the valley from the north. The Marines, along with the brigade tactical command post—Nicholson, the ANA brigade commander, and a small staff—would be dropped by chopper onto mountaintops and were to clear the enemy down into the valley. Their ultimate goal was to set up the Korangal outpost, reach out to the villagers, help establish an Afghan government presence, and kill the enemy: intelligence sources claimed that the insurgent leader Ahmad Shah, thought to be behind the Operation Redwing disaster, plus a known Al Qaeda operative named Abu Ikhlas were in the immediate area.

Fenty had sent Gooding and Able Troop to watch over the southern Korangal Valley while Captain Franklin Brooks and Bravo Troop—who called themselves the Barbarians—moved south into the adjacent Chowkay Valley. Most of Cherokee Company remained back at the base at Naray, with the exception of the kill team, which was also ordered into the Chowkay Valley to patrol for enemy fighters.

The Chowkay Valley was the most popular exit route used by the Korangali Taliban to escape over the border into Pakistan; indeed, Berkoff had briefed Fenty and the 3-71 Cav troop commanders that when confronted by the consistent presence of U.S. troops, the local Taliban leader was likely to “squirt” into Pakistan, after first pushing his team of insurgent fighters into the Chowkay to clear the way for him. The Americans hoped to be waiting there for him.

After they all almost froze to death at twelve thousand feet, Gooding sent Staff Sergeant Matthew Netzel and more than a dozen soldiers from Able Troop’s 2nd Platoon down the Korangal to watch over a lumberyard. Among the troops with Netzel was Private First Class Brian Moquin, Jr., a nineteen-year-old from Worcester, Massachusetts, whom Netzel had kept an eye on since the beginning of their deployment.

When Moquin first arrived at 3-71 Cav, it was clear to Netzel that the private had been a problem child growing up—just like half the Army, in Netzel’s estimation. Back at Fort Drum, Moquin was late to formation one morning at 0630, so Netzel went to his room and banged on his door.

“What’s up, Sergeant?” Moquin said after he finally came to the door, rubbing sleep from his eyes.

“You’re fucking not at formation, that’s what’s up,” Netzel said. “Get your uniform on and get in fucking formation.”

When the slipups continued, Netzel instituted some “corrective” training, ordering Moquin to do pushups, situps, laps—anything to make his whole body hurt for a few days so he wouldn’t ever again forget what a mistake it was to slack. Netzel knew Moquin could potentially be a good soldier; he would always ask questions. After an exercise in which the troops had to disassemble and reassemble their weapons, everyone else in the platoon dispersed, but Moquin remained, repeating the drill.

“Yo, dude,” Netzel said. “It’s time to wrap shit up.”

Moquin smiled at him.

“Out of curiosity,” Netzel asked, smiling back, “what are your thoughts about how you’re hammering down on your weapon?”

“I don’t know about the rest of these guys,” Moquin said. “But I plan on coming home. And if it comes down to a weapons system working, I’m going to make sure there are no problems.”

Fuckin’ A, thought Netzel.

Born and raised in upstate New York, the twenty-five-year-old Netzel understood Moquin in a way that was hard to explain to anyone who hadn’t peered into the chasm of drug dependency and mustered the strength to walk away—in both of their cases, into the welcoming arms of the U.S. military. Back home, Netzel had dabbled in a little bit of everything, without much effect. By the age of eighteen, he’d started to sense that if he stayed in his hometown for too long after graduating from high school, he’d end up in jail or in a coffin. This wasn’t just a working-class cliché; one day, a friend of his, tripping hard, flying around a room like an airplane, dove out the window of a second-story apartment, landing on the pavement. He survived the fall but was never quite the same. Netzel headed for the military not long after that.

“I have a pretty good idea why you joined the Army,” Netzel once said to Moquin at Fort Drum. “But why don’t you tell me why.”

“My life was pretty much going to shit,” Moquin replied. “It was either the Army or end up in jail or dead.”

Netzel had known he was going to say that.

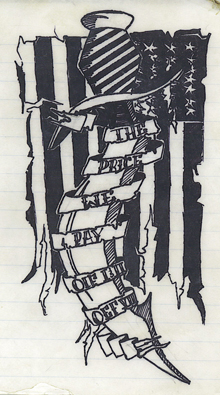

Moquin was a talented artist, and at Naray, Netzel asked him if he’d design a tattoo for him. “This is what I want,” Netzel told him. “A tattered American flag with an Afghan knife. It should also say, ‘The price we pay’ ”—this was the unofficial motto of the 10th Mountain—and should include the designations “OIF 1 and 2” and “OEF 7,” referring to Netzel’s time with the first two deployments in Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and their current stint in Afghanistan, with the seventh rotation for Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). Moquin drew it all out on a piece of paper and gave it to Netzel a few days later.

“Do you mind if I get it, too?” Moquin asked as he handed over the sketch. “Without ‘OIF One and Two,’ of course.”

Private First Class Brian M. Moquin, Jr.’s tattoo design for Staff Sergeant Matthew Netzel. (Courtesy Matt Netzel)

“Hell yeah, do it,” Netzel replied. “You drew it up, it’s your artwork. We’ll go get tatted together when we get back. So hang on to it.”

“No, I want you to hang on to it in case anything happens to me,” Moquin explained, “because I made it for you.”

“Roger,” said Netzel. “I’ll hang on to it, and we’ll get it tatted together.”

Moquin wrote to his mother:

Hi MOM,

How’s everything, I’m doing good. I’ve done a lot of thinking while I was here. I know I haven’t been a great kid and have put you through a lot of things that you didn’t deserve. I haven’t been a good person to many people and I regret a lot of the things I’ve done. But I finally found a place for me. I love it here more than anything. I’ve wanted to get away for so long, I was trapped in my own misery and selfishness. I’ve grown up a lot here, and I’m going to try my damn hardest to make you proud of me. I’m sorry if you don’t hear from me much. I’m very busy and I’m going to be for the next couple years. I love you and I just wanted you to know I haven’t forgot about you.

I’m doing the best I can to be the best soldier.

I miss ya,

Love, your son,

Brian.

And now here they were in the Korangal, Netzel and Moquin, in four feet of snow. Almost none of the other soldiers had been in combat before, so Netzel, having been in Iraq, took the lead as they began their trek.

For nearly all of the troops, the steep mountain descent—during which each soldier carried eighty pounds of gear and ammo at a minimum—was one of the toughest physical challenges of their lives. (And these were young men in top physical condition, trained for just such a challenge.) They had to worry constantly—about falling, about the enemy, and about the clumsy morons up above them (someone up top would accidentally kick a rock loose, and then everyone would shout “Rock!” and try to dodge getting hammered by a mini-boulder). It was a painful, full-day hike down. Climbing up the mountain would have been easier.

On the fifth night, the members of the platoon reached one of the most difficult points so far in their journey, confronting a cliffside so steep they couldn’t descend. They decided to call it a night. In the morning, they’d figure out where to go next.

Sergeant Michael Hendy was on guard duty; he sat behind a rock wall in the pitch black, staring at the path. He heard a hissing.

“I think a battery’s leaking,” Hendy whispered to Moquin. Batteries for the thermal scope were stacked up for the night; filled with a gas, they would make a “Ssssss” sound if they cracked. Hendy turned on a thermal light so he could fix the problem. A four-foot-long pit viper was angrily staring him in the face, raised as if it were coming out of a snake charmer’s basket.

Holy shit, Hendy thought.

He jumped back and bellowed for the lowest-ranked private, Taner Edens, to get the snake. Edens snatched up a KA-BAR combat knife.

“Attack!” Hendy yelled from behind Edens, pushing the private toward the snake. The viper turned toward Edens and hissed.

“Abort! Abort!” yelled Hendy, running.

Edens swung. Although the viper was nicked by the KA-BAR knife, it managed to slither off into the brush. The snake’s escape didn’t make it any easier for the men to get to sleep, but sheer exhaustion soon took over, and they slumbered.

That is, until later that night, when Moquin shook Sergeant Jeremy Larson awake.

“There’s contact in the woodline,” Moquin whispered. The enemy was out there.

The men got ready. Specialist Shawn Passman crawled over to them in his underwear.

They sat and waited.

No sounds.

Nothing.

Larson peered through Moquin’s thermal sight, a camera that picked up infrared radiation, including body heat. He saw the same thing Moquin had seen but caught one detail the other man had missed: the “enemy” was sitting about thirty feet up, in a tree that grew off the cliff.

That can’t be the enemy, Larson thought.

He grabbed a blue light and shined it toward the tree.

It was a monkey.

While much of Afghanistan was known for its barrenness, monsoon rains from the subcontinent reached the eastern part of the country, filling the northeastern region with stands of cedar, walnut, fir, oak, pine, and spruce trees. Combined with the clear, untamed streams and rivers of Nuristan and Kunar Provinces, the trees made for gorgeous vistas that reminded some troops of luxury fishing spots in Wyoming or Montana, the kind they’d read about online or in brochures. The one disconnect—other than the insurgents trying to kill them—was the variety of animals they encountered: rhesus monkeys and leopards, horned vipers and wild cats, six-foot-long lizards. More than once, the men stopped to watch as nasty porcupines beat up feral dogs; it became something of a spectator sport. Even more disconcerting were the insects and other critters, including centipedes that were longer than a man’s foot, three different types of ants (little red, little black, and crazy-fast tall red), a giant red bee of some sort, scorpions, wolf spiders, and infestations of grasshoppers.

The fauna of their new home often came as a surprise to U.S. troops. Here, Sergeant Paul Rozsa is introduced to a lizard by an Afghan soldier. (Photo courtesy of Marine Lieutenant Chris Briley)

Most terrifying of all, though, were the enormous camel spiders, which were technically not spiders17 and really didn’t look as if they were even from this planet. They were typically the size of a soldier’s hand, sometimes even bigger, brown in color and with metallic, helmetlike bodies and hairy legs on which they could run as fast as ten miles per hour. Camel spiders were fully capable of eating lizards, scorpions, or birds for dinner. Although not venomous, they could inspire quite a jolt by falling on a soldier in his tent or deciding to seek shade in his sleeping bag. To pass the time during dull stretches, some of the troops would put two of them in a box together and watch them fight.

A few days later, Netzel and his men finally arrived at their destination. Those troops not pulling security were allowed to eat and rest. Netzel and Moquin made small talk about their small-town pasts. Moquin had moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, from nearby Shrewsbury and had to switch high schools, eventually obtaining his GED from a local community college. His parents had split when he was just a year old, he said, and his dad, who wasn’t a part of his life, had spent time in prison because of his problems with drugs. Moquin himself had wrestled with drugs; he had been hooked on heroin at one point, before he joined the Army. He had tried it for a simple reason: “I wanted to see why my father loved it more than he loved me,” he said.

Originally the plan had been for the 2nd Platoon to watch over the valley from its post for two days and then return, but over the radio, Sergeant First Class Milton Yagel told Netzel that his orders now were to push to the next mountaintop and head down the side to link up with Frank Brooks and the Barbarians, who were planning to meet with the elders at Chalas.

This would end up being a twenty-six-mile haul. During the day, the sun would beat down on the troops oppressively, but after dark, it was bone-chilling cold. One night, Netzel and Moquin shared a hollowed-out tree in which they slept standing up. Before drowsing off, they talked about Moquin’s girlfriend; just before arriving at the base at Naray, he’d changed his life insurance policy to make her his beneficiary.

“Hey, Sarge,” Moquin said. “What do you think about this?”

Netzel grunted. He was exhausted.

Moquin went on about how, on R&R, he was going to surprise his girlfriend.

“Surprise her with what?”

“I’m going to ask her to marry me,” Moquin explained. The plan was that he would buy an engagement ring, slip it onto a dog collar, put the collar on a puppy, and give her the pet as a sort of double surprise.

Fenty was focused on his men, focused on their missions, but there was something else that occupied his thoughts as well. His wife, Kristen, was one week overdue with their baby. In the green commander’s notebook he carried with him everywhere, in the midst of his penciled notations about intel—“New personality in Waygal18: Diyan.… Has supplies to equip 10X Suicide Bombers”—he had highlighted in black Sharpie “Kristen’s Contact Info,” with phone numbers for the Samaritan Medical Center near Fort Drum, including Daytime Triage and Evening Maternity, as well as his wife’s friends.

“Don’t you want to go back for the birth of your child?” Colonel Nicholson had asked him.

“Kristen and I talked about it,” Fenty replied. “Right after the baby’s born, she’ll be tired and off her feet.” It’d be better if he waited just a little bit, giving her some time to recuperate. “I’ll fly back after Mountain Lion,” he said. “My mom’s there for her.”

As her due date got closer, and then passed, he would call Kristen for news—also speaking to his mother, Charlee Miller, who had driven up to Fort Drum from New York City—but each time the answer was the same: nothing yet. On Friday, April 7, Kristen paid an ambitious visit to a midwife who, hoping to speed things up, expanded her cervix in an attempt to bring on labor.

Early on the morning of April 8, through the unofficial but often far more efficient lines of communication run by military wives, Fenty, in a tiny broom closet of an office at Jalalabad Airfield, heard the news via emails and other messages: Kristen was in labor and about to deliver their baby girl. Her water had broken, and with the aid of her mother-in-law and Andrea Bushey—the wife of Lieutenant Colonel Dave Bushey, also in Afghanistan—she had gotten into a car, in which the three women had then driven through a blinding upstate New York snowstorm to get to the hospital.

Heart racing, Fenty called her cell phone. Kristen answered.

“They said it’s going to be a long time,” she informed him. They spoke for a little bit before he told her he’d call again as soon as he could. It was after midnight her time.

At 8:09 a.m. on April 8, the phone rang again in Fort Drum. Fenty was calling back.

“I’m going to take this,” Charlee Miller told the nurse.

“Joe,” she said as she answered Kristen’s phone.

“Mom,” he said, obviously desperate for any news.

“Joe, your baby is going to be born right now!” she told him.

At that moment, Kristen let out a bellowing scream, and Lauren was born.

“Stand by,” Fenty’s mother said. “You’re going to hear your baby cry.”

Within seconds of the medical team’s suctioning baby Lauren’s windpipe, she started screaming, and her skin flushed with a beautiful pinkish hue.

“Is she all right?” Fenty asked.

“She’s all right,” his mother told him.

“Is that the father on the phone?” asked the doctor. “From Afghanistan?”

“Yes, Doctor,” Charlee Miller said.

“She’s beautiful!” the doctor shouted to Fenty.

“How much does she weigh?” asked Fenty.

“I don’t know yet,” said his mother.

“I’m going to lose you,” Fenty said. “I only have seven seconds left.”

The line went dead.

He got through to Kristen herself later in the day. She was weepy. She was worried about him; he was worried about her.

“What’s wrong with you?” he asked her, unaware of how difficult childbirth could be and used to his wife’s being lucid—not exhausted, hormonal, and recovering from an epidural. Kristen explained her condition.

“What does she look like?” he asked.

“She’s beautiful,” Kristen said.

On April 19, Staff Sergeant Willie Smith led three other soldiers from Bravo Troop to the Korangal Valley’s Abbas Ghar Ridge, where they were put under operational control of the 1-32 Infantry Battalion. Their job was to watch the valleys, the villages, and those sections of the road that were considered particularly vulnerable to insurgent attacks.

They were using a long-range advance scout surveillance system, or LRAS, which allowed thermal-optical surveillance up to fifteen miles, meaning that troops not only could see bodies from a long distance away but also could use the device to confirm enemy deaths, watching bodies lose life as heat from them was slowly—or not so slowly—released into the air. The LRAS in and of itself made obsolete other systems that required scouts to position themselves within the range of enemy fire. This technological advance came with strings attached: it was a terribly expensive and unwieldy machine, weighing about 120 pounds and difficult to haul across inhospitable mountains. The sight—through which scouts would look for the enemy—was as bulky as a medium-sized safe or a 1980s-era living-room television set, at seventeen inches high, twenty-seven inches wide, and thirty-one inches deep. And yet, by 2006, the Raytheon Corporation was closing in on selling its thousandth unit to the Pentagon.

There were just two spots where the LRAS could be set up to cover the first “named area of interest” to which these soldiers from Bravo Troop, 3-71 Cav, had been assigned. One was on a ledge above a steep precipice. The other option would put the LRAS on more stable ground, but trees and other vegetation would interfere with its field of view. Staff Sergeant Smith and his team concluded that the ledge was the only feasible choice.

On April 21, Sergeant Jake McCrae had been scanning the assigned area as instructed for about half an hour when the LRAS’s batteries began to die. As he was in the process of replacing them, a gust of wind hit the LRAS, pushing it over the cliff. McCrae tried to hold on to the right-side handle, but there was no stopping the heavy machine once physics became involved. The half-million-dollar piece of equipment crashed at the bottom of the cliff.

In the larger scheme of possible disasters in a war zone, the loss of an LRAS meant very little. But the Pentagon bureaucracy did not see it that way: soldiers were routinely required to account for every tax dollar spent, and the threat of having the cost of any lost equipment docked from their paychecks could loom large. The subsequent investigation into the loss of this LRAS would cause strife among the leadership of 3-71 Cav and, in the end, beget a tragic irony.

It began at 3-71 Cav’s new logistical base in Kunar, where Fenty assigned Ben Keating to figure out what had gone wrong and whom to punish for it.

Keating did not want this job. He wasn’t eager to punish enlisted men. He identified with them; he felt like he was there to serve them. As a member of the youth leader corps in his parents’ church, Keating had taken to heart the notion of leading as a servant, as Jesus had done. He would tell his mother that he’d learned more about how to lead a platoon from youth leader corps than from any of the training he’d gotten at boot camp.

Keating’s easygoing veneer masked a complicated mix of self-righteousness and actual righteousness. The intensity of his religious faith was of such an order that even his parents, both of whom were Baptist ministers, sometimes found it jarring. When he was a child, they’d joked that he knew more about the Old Testament than they did. Keating had been something of an odd kid, to be sure, spending hours reading his David C. Cook Picture Bible, a 766-page comic-book version of all the texts from Genesis through Revelation. He was particularly taken with the stories of King David and the tale of Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, as rendered in the comic book:

PETER: “No, Lord, I’m not good enough to have you wait on me!”

JESUS: “If you do not let me serve you, Peter, you will have no place in my kingdom.”

After Jesus has washed all of the disciples’ feet, he sits down at the table again.

JESUS: “If I, your lord and master, have served you, you should do the same for one another. The servant is not greater than his master.”

And that was Ben Keating. “You don’t ever ask your soldiers to do anything you wouldn’t do,” he would say. “You have to serve them to get the best leadership out of them.” Other soldiers might have come to the same conclusion in their own ways, but it was a safe bet that Keating was the only member of the 10th Mountain Division who’d brought with him to Afghanistan a copy of The Confessions of Saint Augustine—in Latin.

Keating had a true sense not only of service but of mission as well—and not the small kind, either. During college, after one young woman made it clear that her feelings for him were more like those of a sibling than those of a potential wife, Keating talked it over with his mother. He was very close to both of his parents.

“So how are you with that?” Beth Keating asked him.

They were walking in the woods behind his parents’ house.

“I’m okay, Mom,” Keating said. “I think I’m supposed to be doing something bigger with my life anyway.

“I need to do this,” he went on, referring to his military commitment. “So I guess this isn’t the time for me to be thinking of a long-term relationship anyway.”

What Keating was now doing in eastern Afghanistan wasn’t what he’d had in mind when he talked about serving his troops. All the paperwork made his head hurt, and he’d be in a bad mood all day as he solved problems for people who seemed to him incapable of doing anything for themselves. He would personally sign for some four to five million dollars’ worth of equipment daily—money he could never possibly pay back if something got irresponsibly damaged or mislaid. This man whose knowledge and devoutness rivaled those of a cleric was being consumed by work almost entirely clerical.

Now Fenty had ordered him to look into whether Willie Smith and Jake McCrae should have their pay docked for the loss of the LRAS. Keating found the very idea maddening; he saw this as one more instance of the typically myopic Army-brass sensibility that got underneath his skin and irritated him like a rash. He emailed his father, seeking guidance. The maximum pecuniary charge that Smith and McCrae faced was forfeiture of two months’ pay. Keating figured that penalty would add up to about one fiftieth of the cost of the LRAS, barely enough to buy one of the system’s power cables. He also reasoned that if the Army hit the two men that hard, neither would be likely to reenlist. Taxpayers had every right to seek an accounting for the lost LRAS, but was it really worth losing these two soldiers over? Had there truly been gross negligence? They were at the end of the Earth here, and for the love of God, the mountains of the Hindu Kush were windy. He was inclined to give the soldiers letters of reprimand—still a slap in the face, but one that might keep them in uniform.

Keating discussed his investigation and his thinking with Fenty, who pushed him to make a tougher ruling. Keating suspected that part of what motivated the squadron commander was a desire to impress his bosses, and he resented Fenty for putting him in that position. He resented him even more when he overheard him telling Major Richard Timmons—the squadron XO, and thus the middleman between Fenty and Keating—that he wondered if Keating had the “moral courage” to render such a judgment.

It would be hard to imagine a remark that could have insulted Keating more.