Before he left on the mission with Cherokee Company’s kill team, twenty-eight-year-old Sergeant Patrick Lybert called his younger brother, Noah, back in Ladysmith, Wisconsin, to coordinate a different operation altogether. Lybert was scheduled to return to Fort Drum on leave the following month, July 2006, to visit his fiancée, Carola Hubbard. He had secretly paid for plane tickets for Noah and their mother so they could come to the upstate New York Army base for a surprise wedding.

Because nineteen-year-old Noah was a special-needs kid, Lybert had to make sure he fully comprehended that this was a secret he was supposed to keep not only from Carola but from their mother as well. (Noah understood.) Lybert had always been protective of his younger brother. One classmate in the fourth grade had ended up with a black eye after he suggested that Patrick was something less than a full brother to Noah, who technically had a different father, their mother having divorced and remarried. After graduating from high school, Lybert had told his mother, Cheryl Lee Nussberger, “Don’t worry, Ma, I’ll take care of Noah.” He said he wanted to become Noah’s guardian after she passed away.

“Well, Pat, you may have a wife who feels differently,” his mother pointed out.

“Nobody will ever be part of my life who doesn’t accept Noah,” Lybert replied. And Carola fulfilled that prophecy: once Patrick got out of the Army, the two of them intended to move back to Ladysmith. It was all part of the plan and the promise.

When Patrick was home on leave that past January, before being deployed to Afghanistan, his mother had noticed that he seemed to have a new weight on his shoulders. He was due to become a recon team leader, and he took his leadership responsibilities seriously. He couldn’t be a pal to his troops, he knew; he had to be tough on them so they would be prepared. “Some of these guys are so green, they’re going to get themselves killed,” he fretted to Cheryl. “Mom, if any of those guys I’m responsible for get killed, I will never be able to live with myself.” So, like any good mother who saw her child worrying, she worried, too.

Lybert joked around a lot—he gave the impression of being a fun-loving, outdoorsy type—but he went into the military with grief in his soul, Cheryl always thought. It predated the Army. Two of his high school friends had died in freak accidents shortly after graduation. Later, when he was working as a “loss-prevention specialist” for the midwestern retail chain Shopko, in charge of preventing the theft of merchandise, he’d twice caught young men stealing from the store, and both times they’d ended up killing themselves. One, a seventeen-year-old fellow employee, was videotaped setting goods outside the back door for coconspirators to pick up. Lybert confronted him because that was his job, but then a couple of days later, the boy’s aunt called and asked him if he was happy to know that the kid had taken his own life. The other was a foreign exchange student whom Lybert caught shoplifting. The student got on his hands and knees and begged him for mercy, but there was nothing the loss-prevention specialist could do—he was supposed to stop thefts, and this kid, too, was on video. The student was later found floating in a lake. These incidents haunted Lybert.

He’d joined the Army in 2002, done a tour in Iraq, come back, and jumped from 1-32 Infantry to do recon for a new squadron that was being formed at Fort Drum, 3-71 Cav. He loved the Army and had just reupped in March, though he was also eager now to start a family. More immediately, he was looking forward to returning to Fort Drum on leave, to seeing Carola, his mom, and his brother.

“I got the tickets booked,” he told his mother, referring to the flight she and Noah would take to upstate New York to meet him.

“I told you not to do that—I’ll pay!” she protested.

“I already bought the tickets, Mom,” he said. “Hey, I’m going out on this mission. I’ll call you when I get back. I love ya, Ma.”

“I love you, too,” Cheryl said into the silence. “Patrick, I love you.”

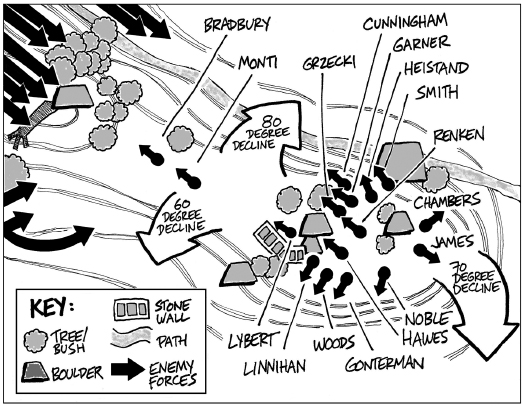

Patrick Lybert didn’t normally work with the kill team, but because three soldiers from Cunningham’s regular group weren’t available—two were on leave, and the third was recuperating from a hernia operation—he and three others went along on this mission. On the night of June 19, Cunningham and Monti led fourteen soldiers in a convoy to a mortar position south of Bazgal, near the Gawardesh Bridge. From there, they began their ascent up the ridge. Because it was crucial that no one see them, they took the most difficult route. Heading up to a ridgeline overlooking the Gremen Valley, they climbed until sunrise. During the day, they rested and conducted surveillance.

The slopes were steep, and their rucksacks were jammed with sixty to a hundred pounds of gear apiece. The men had to tread carefully for fear they might trigger a Soviet-era landmine, fall down the mountain, or, at the very least, sprain an ankle. It was June in Afghanistan, so the temperature shot up to close to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and the rough climb sapped every bit of their energy. They didn’t talk—they had to keep quiet—and Sergeant Chris Grzecki, for one, spent much of his time just praying for the torturous mission to be over.

On the second day of their trek, the troops saw two Toyota Hilux pickup trucks drive into the valley, each loaded with men. After the sun set, the Americans watched headlights flow along the road. It seemed suspicious to them, all of that driving during late hours of the night and through the early morning.

At dawn, they continued their ascent. Specialist John Garner served as point man for the kill team, which meant that he blazed the trails, and he always chose routes that were preposterously far off the beaten path. Sometimes this annoyed those traveling with him, Garner knew, but that was okay with him: he was point, and he would be the first one to get shot or blown up if he made the wrong choice. The others could go where he wanted to go.

Garner and Specialist Franklin Woods led the way up the mountain and into a thicket of Afghan pines, the rest of the team following twenty yards behind. Garner was heartened to see the untrammeled pine needles spread across the steep mountainside, covering the ground like a thick carpet, suggesting that the enemy had not been there. And then he noticed a pattern of indentations in the needles, with the ground visible underneath in places.

Footprints.

He called his team leader—John Hawes, the good shot who’d scored his first kill during the Kotya Valley mission—and showed him the evidence of the path, in a steep area where only someone trying to go undetected would walk. The coordinated pattern of broken needles and patches of dirt suggested a group of people walking in single file, Garner thought. Hawes looked and nodded.

“Push forward,” he told Garner. “Keep your eyes open.”

Garner did so, his sniper rifle pointed out in front of him, his finger on the trigger, the hair on the back of his neck standing at attention. Finally, the team arrived at the top of Hill 2610, where they set up camp in a small clearing on a flat but narrow ridgeline that reminded Hawes of a knife’s edge. At an elevation of roughly eighty-five hundred feet, the area measured approximately 160 feet long by 65 feet wide; it sloped downward from north to south and had a tiny goat trail running along its eastern edge. Some of the men set up on the northern side, behind some trees and heavy brush. A few smaller trees, several large boulders, and the remains of a stone wall marked the southern end of their position. Using their scopes, they watched the valley to the east, beyond the steep slope. Normally, the members of the kill team would carry enough food and water to last them for five to seven days, but by the time they all got to the summit, on the third day of their trek, they were almost out of—or “black on”—water. Cunningham called that status in to the base.

About an hour after the team set up camp, Garner saw six men through his spotting scope. They were about two and a half miles away, heading toward them from the Pakistan border. He alerted his chain of command, and soon Cunningham came over to take a look. Were they insurgents? Friendlies? Afghans? No one knew. From the observation point, the Americans could see a suspected HIG safehouse and Haji Usman’s home.

Cunningham and Monti were pleased. This, they felt, was a good location.

At Forward Operating Base Naray, Howard called in Brooks and Captain Michael Schmidt, the new commander of Cherokee Company (replacing Swain, who’d been transferred to Peshawar, Pakistan, to work at the U.S. Consulate).

The squadron was supposed to launch into Gawardesh that night or early the next morning, helicoptering in troops from Barbarian Troop and Cherokee Company and entering the village. Were they square? Howard wanted to know. Were they good to go?

Brooks said yes; Schmidt said no. One of his men had just been seriously wounded by an IED, and Cherokee Company needed about twenty-four hours to get things straight.

Years later, the fact that this whole mission was delayed because one man had been wounded would gnaw at Jared Monti’s father, Paul. More than once, Jared had complained to his dad that the United States didn’t have enough troops in Afghanistan. There weren’t enough resources, he said; there weren’t enough helicopters.

Paul Monti, a public high school science teacher, was already incensed by what he saw as a near dereliction of duty by President George W. Bush and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who for some reason had focused all their attention and the great majority of their available manpower on the war in Iraq. In doing so, Paul Monti believed, they shortchanged his son and all the other troops who were fighting in the very country where those responsible for 9/11 had laid out their sinister plans. Why would Bush and Rumsfeld, Paul Monti wondered, send these kids into war without making sure they had enough support and supplies? Why would they create a dynamic that allowed the wounds of one man to jeopardize an entire mission?

On Hill 2610, Cunningham was informed that the mission would be delayed up to forty-eight hours, but he wasn’t told why—and it didn’t matter why, really. Soldiers did as they were told. But he made it clear to the commanders back at Forward Operating Base Naray that given the change in circumstances, his men would need a resupply of food and water as soon as possible—420 bottles of water and 160 MREs if they were going to have to last four to five more days on the ridge, as was now the plan. A resupply would unquestionably alert the enemy to their presence, but they had no choice. (They had previously been scheduled for a resupply in conjunction with the pending “air assault,” during which troops would be choppered into the area.) All Cunningham could do was request that the chopper drop the supplies as far as it could from their observation post, and in an area not visible to any insurgents in the Gremen Valley.

At about 2:00 p.m. local time, a Black Hawk helicopter dropped the speedball—a container packed with supplies, designed to withstand a fall—around five hundred feet north of Hill 2610, above a ridge on a different mountain.

This is making a bigger signature than I wanted, Cunningham thought. It’s too close to us, drawing too much attention. He decided that he would lead eleven soldiers over there to recover the supplies. It might be something of a hike, Cunningham warned them; they should be sure to conserve their water.

Four men stayed behind to keep watch, including Grzecki and Specialist Max Noble, a medic. Through his scope, Noble saw an Afghan with military-style binoculars standing in the valley near a large house, seemingly looking right at them. Although he was carrying a large bag, he didn’t have a weapon visible, so the Rules of Engagement prevented Noble from doing much more than noting his location and assigning a target reference point to the building, which he did.

The expeditionary party, led by Cunningham and Monti, now returned with the dropped supplies. Everyone guzzled down water. Noble told Cunningham what he’d seen and then pointed out where the man with the binoculars had been standing.

An hour or so later, on the goat trail adjacent to the team’s position, two Afghan women in blue burqas appeared, carrying bags of wheat. They slowly approached the Americans. All that Cunningham, Monti, and the other men could see of them was their eyes, whereas those same eyes could see everything about them: the number of U.S. troops; where the heavy guns were positioned; where they’d placed the rectangular Claymore mines that they’d scattered around the camp, set to detonate against any enemy attackers who got too close.

The soldiers looked at one another. What should they do? Should they detain them? For what? For walking in their own country? Garner stood on a boulder above the women, peering down at them. One woman signaled with her hand to ask if she and her companion could pass by. She pointed at a Claymore. The mine was hidden, but when you lived in a country littered with explosives, you learned to watch where you walked.

Garner signaled for her to pass on the trail; she shook her head no and gestured to indicate that she wanted to take another route, circling around their makeshift camp, hugging the cliff, and then heading off into a thick cluster of woods. The soldiers allowed the women to go that way.

As the sun set on the valley, Cunningham, Monti, and Hawes stood behind a big rock and began talking about moving to a different spot. If they did that, they would have to travel on a new path, which was always a risk. That’s how the enemy slays U.S. soldiers, Cunningham thought: he waits until we’re in a vulnerable place. And there was no guarantee they’d be able to find a better, more defensible post—this area of the ridgeline was wider than others, and there were a few big boulders here that they could use for cover.

They were discussing doubling the number of troops on guard shift for the night when an RPG exploded in the tree above them.

While there are many different types of grenades and RPGs, in general an RPG may be pictured as resembling a rocket about the size of a man’s forearm. When fired from a tube, it becomes something like a combination of an immense bullet and an explosive. RPGs can take down helicopters and stop tanks; human bodies—flesh and bone, muscle and tissue—pose little impediment to them.

First comes the force of the explosion, the blast wave that inevitably knocks soldiers down and perhaps knocks them out. The high-pressure shock wave is followed by a “blast wind” that sends an overpressure through the body, causing significant damage to tissue in the ears, lungs, and bowels.

If a soldier survives the initial hit of an RPG and manages to regain his bearings, only then will he notice the effects of the considerable shrapnel produced by the device. The RPG’s casing, now in the form of myriad penetrating fragments, will have been hurled in all directions. The irregular shape of these fragments can slow down their trajectory as they fly through tissue, at times making their impact more painful than that of a bullet. A leg or an arm may be turned to mash or even liquefied by shrapnel. If you’re a soldier in battle and an RPG hits a tree near you, you get down and hope that another one doesn’t land closer.

The first thing Smitty did was look at his watch to see what time he was going to die.

Private First Class Sean “Smitty” Smith was lying down and just putting out a cigarette—a local brand called Pine Light—when the shooting started. He and six other troops were at the northern end of the team’s position, near the treeline. The other five were Franklin Woods, Brian Bradbury, Private First Class Derek James, Specialist Matthew Chambers, and Specialist Shawn Heistand.

Woods had heard a shuffling of feet, but before he could say anything, the shooting started, the fire coming so quickly and so ferociously that many of the troops didn’t even have time to grab their weapons.

There were approximately fifty Afghans shooting at them from about 150 feet away to the north, and some more immediately to the west—all so close that the troops near the treeline could see their faces as they fired at the Americans with their Russian-made PKM machine guns. Those faces looked calm and collected, wearing the kind of expression that might otherwise be seen at target practice. The insurgents firing the RPGs were to the northwest.

Smitty was scared. This was his first firefight ever. There wasn’t much for him to take cover behind, though he didn’t think the enemy fighters had noticed him yet. But sooner or later, they surely would.

Smitty and Bradbury were the squad automatic-weapons (SAW) gunners, the designated carriers of portable light machine guns, which produce a heavy volume of fire with something approaching the accuracy of a rifle. Bradbury, lying on his stomach on the front line, used his SAW to suppress enemy fire as best he could. Heistand was firing as well, with his assault rifle.

Smitty didn’t have his SAW with him; he’d earlier placed his gun in the spot where he was due to stand guard duty that night. On his belly, he low-crawled backward to a small clearing and snagged a different gun, a sniper rifle. Walking backward, he slowly fired a series of well-aimed shots, then turned around and ran back to the rest of the group behind the boulders.

This attack was distressing not only for newbies such as Smitty but also for the more veteran of the men. The hell they were in represented the most intense enemy fire ever experienced by Cunningham, who was on his fourth tour in Afghanistan. The PKM machine guns the insurgents were firing could deliver up to 650 rounds per minute, and the Afghan RPGs were coming in quickly, one after another after another. Pretty much all the Americans could do was duck behind their cover, hold their weapons above their heads, shoot, and pray.

Using his call sign, “Chaos Three-Five,” Monti radioed to squadron headquarters.

“We’re under attack by a much larger force,” he reported. “We need mortars, heavy artillery, and aircraft to drop bombs.”

Monti paused for a minute. Remaining behind the boulder, he fired his M4 carbine rifle toward some approaching enemy fighters to the west of him. Then he threw a grenade at them. It didn’t go off, but it caused the insurgents to scatter.

Back on the radio, he called in the two sets of coordinates, for the Americans’ position and the insurgents’, stressing that they were “danger close”—meaning that the insurgents were in such tight proximity to their prey that there was a significant risk that any mortars fired or bombs dropped might kill Americans, too. But there was no better option, since at this point it looked as though they would soon be overrun.

Shortly thereafter, several mortars landed to the north of the American camp. A mortarman asked Monti by radio if he should adjust his fire, but the enemy bullets and RPGs were flying so furiously that Monti told him he couldn’t even raise his head to check where the mortars had hit. He’d just have to keep his fingers crossed and hope they were hitting their mark.

Grzecki and John Garner had been sitting on the eastern part of the hilltop with their spotting scopes, observing the valley, when an RPG exploded in the tree four feet away from them. They promptly dove behind a small boulder for cover, but within moments, the fire was so intense that they couldn’t get to their weapons. Grzecki’s rifle was sitting next to him, but a flurry of bullets kept him from reaching for it. Garner grabbed his rifle, but when he stood to return fire, an enemy fighter shot it right out of his hand.

Lybert was in front of Garner, crouching behind the small stone wall to the west. Specialist Daniel Linnihan was farther down, also behind the L-shaped wall.

“I need a weapon!” Garner shouted to Lybert.

“Where’s yours?” Lybert shouted back.

“It got shot out of my hand!”

“Stay behind cover!” Lybert told him, popping back up just far enough that only the top of his helmet, his eyes, and his rifle were exposed. He continued steadily returning fire at the enemy as the small stone wall he was behind began getting hit with machine-gun fire, chipping the rock and sending up puffs of gray dust. Lybert pulled the trigger of his gun yet again, but then, as Garner looked to him, he stopped, just stopped, and blood started to spill from his right ear. Lybert fell forward.

“Lybert’s been hit!” Garner yelled.

Garner fell onto his chest, getting as low to the ground as he could. He wanted to move backward, behind the boulders, but he was afraid he’d get killed if he did.

Behind the cover of the small stone wall, Linnihan crawled over to check on his friend. Lybert was gone.

“Throw me Lybert’s weapon!” Garner yelled to Linnihan.

Linnihan reached under the shoulder of the dead soldier, grabbed his M4 rifle, and tossed it to Garner.

“Cover us while we move,” Garner and Grzecki screamed to Cunningham and the others behind the boulders.

“Move!” the team yelled back, providing suppressive fire as the two ran to join them behind the larger boulder, followed by a wave of RPGs. Grzecki did a quick check. He could see where every American was, with the exception of Bradbury. The troops at the northern end of the position, near the enemy, had been retreating; Chambers, Smitty, and Woods had made it to cover safely.

Derek James had not. “I got hit in the wrist!” he cried as he low-crawled toward the boulders. “I got shot in the back!” Grzecki reached out and grabbed him and pulled him behind the rocks, where Chambers began treating his wound with gauze, trying to stop the bleeding, unsure whether the bullet had ripped across his back like a skipping stone or drilled in.

The insurgents seemed to be coordinating their movements. While about a dozen of them pushed in directly from the north, others fired RPGs from the northwest, and a third, smaller group started creeping toward the Americans from the goat trail to the east. In their northern position near the woodline, Bradbury and Heistand could hardly have been more exposed: the enemy could see them clearly, and they could see the enemy.

“We need to get to better cover,” Heistand told Bradbury. “Let’s go!”

Heistand jumped up and retreated toward the boulders. When he arrived at the rocks, Bradbury was no longer with him.

Cunningham had been kneeling behind a tree stump engaging with the enemy; he could feel rounds hitting the wood. Some of the insurgents were close enough that he could hear their low whispers.

Everyone had been calling Bradbury’s name for several minutes, with no response. Cunningham loved that kid with the steely gray eyes. He was a soldier’s soldier: he did what he was told. He was smart and tough. As they were hiking to the summit of Hill 2610 just a few hours earlier, Bradbury had told Garner and Lybert that he’d had something of an epiphany: after his deployment, he was going to go home, work things out with his wife—with whom he’d been having problems—and raise his three-year-old daughter, Jasmine, the right way. That conversation now seemed as if it had happened a month ago.

Cunningham was convinced they couldn’t retreat, primarily because Bradbury was still on their front line, but also for another reason. He believed that if they were to fall back and withdraw down the steep 70-degree slope behind them, they would be repeating a mistake made by the Soviets two decades before. He had studied those battles closely, and he felt certain that if his team gave up the high ground, the insurgents would then be able to pin them down and finish them off. That was why the Russians had never been able to make any progress in the mountains of Afghanistan, Cunningham thought. The best way to fight here was to fight like the enemy, to own the high ground or meet him at the same altitude.

“Bradbury!” Cunningham yelled. “Bradbury!”

Quietly, Bradbury managed to say, “Yeah?” From his voice alone, it was hard to tell where he was—fifty feet away? a hundred?

“You okay, buddy?” Cunningham asked.

“Yeah.”

“Okay, buddy, we’re going to come get you.”

Once the others realized that Bradbury was talking to Cunningham, they started cheering him on—a somewhat incongruous sound amid the heavy volume of rocket and machine-gun fire they were still taking.

“Don’t worry, buddy, we’re going to get you!” yelled Staff Sergeant Josh Renken.

Cunningham and Smitty were in a decent position to low-crawl to where they thought Bradbury was and drag him back.

“I’m going to get him,” Cunningham said.

“No, he’s my guy,” said Monti. “I’ll get him.”

Monti tossed Grzecki his radio. “You’re Chaos Three-Five now,” he said, transferring his call sign, then shouted to Bradbury, “You’re going to be all right! We’re coming to get you!” Monti stood and ran north, toward Bradbury and the enemy, away from the cover of the boulders, immediately prompting an eruption of machine-gun fire from the insurgents. Diving behind the small stone wall where Lybert’s corpse lay, he paused, then stood and began pushing toward Bradbury. The enemy fired upon him again. He dove back behind the wall.

“I need cover!” Monti called to his men.

Hawes grabbed an M203 launcher to fire grenades at the enemy. Others snatched up their rifles.

“I’m going to go again!” Monti yelled, and once again he stood and ran toward Bradbury. Monti’s quarry was lying on his back, about sixty feet away, in a small depression in the ground that hid him from both the U.S. troops and the insurgents. Bradbury was in agony; an RPG had ripped apart his arm and shoulder.

Now another RPG found its mark, slamming into Monti’s legs, setting off its shock wave and filling the air with shrapnel.

The dust cleared. “My leg’s gone!” Monti screamed. “Fuck!” His leg was in fact still there, but it had been deeply cut by the shrapnel, and he was now in shock. When he tried to crawl back, he couldn’t. “Help me!” Monti cried. “Cunny, come get me,” he pleaded with Cunningham, obviously in excruciating pain. “Come get me.”

Cunningham stood and started to move, but the fire was too intense, both from the insurgents, who were frighteningly close, and from the U.S. troops returning their fire. He would have had to run through rounds. Hawes began low-crawling toward Monti, but even on the ground, there was only so far he could go.

For a short while, Monti’s fellow troops listened to him scream as he bled out. From a distance, they tried to keep him calm, asking him questions between rounds of returning fire.

“What are you going to do when you get home on leave?” one asked him. “Will you drink a beer with me?”

“Tell my mom and dad I love them,” Monti said, his voice fading.

“You’ll tell them yourself!” yelled Hawes.

Cunningham could hear an enemy commander shouting out orders to his men.

“Tell them I made my peace with God,” Monti said.

He begged for the release of death, and finally it came.

From afar, the fire-support soldiers kept sending mortars that exploded on the ridgeline above the kill team, and as the sun set, Grzecki directed planes that began dropping five-hundred- and two-thousand-pound bombs about five hundred feet away. That was enough to abate the enemy fire.

Cunningham moved up and provided cover, firing his M203 grenade launcher. Hawes reached Lybert and—after confirming that he was dead—gathered up his ammo and threw it back behind the boulders. Insurgents fired at him; Hawes shot back with an M16 rifle that he found near Lybert, then threw a grenade. Next he scurried over to Monti. Also dead. He took and tossed his ammo, too.

Hawes then moved on to Bradbury, where Smitty met him. Bradbury was still alive, though the RPG blast had done serious damage to his arm. Together Hawes and Smitty carried him toward the boulders. Along the way, they passed Monti’s body.

“Who’s that?” asked Smitty. The fire had been so loud, and the fight so all-consuming, that Smith hadn’t been aware of everything that was happening, even just a few yards away.

“Monti,” grunted Hawes.

They passed the stone wall.

“Who’s that?” asked Smitty.

“Lybert,” Hawes answered.

Noble, the medic, immediately started working on Bradbury. His arm was so badly mangled that Noble had to wrap the tourniquet around his shoulder since there wasn’t any place left to put it on the limb itself. The medic showed Garner where to hold the special quick-clotting combat gauze on Bradbury’s wounds. The gauze burned a bit as its embedded chemical did its work, sealing the skin and flesh.

“You get to go home now,” Garner reassured him. “You get to see your baby early.”

More rounds came toward them, and Hawes got Garner’s attention and pointed to Bradbury’s weapon.

“Get to it,” Hawes said.

Garner ran back to Bradbury’s SAW and started firing. Smitty joined him. Grzecki radioed back to the base: they needed to get a medevac in there, he told them. By now, darkness had fallen upon the mountain.

The enemy retreated, and the kill team assumed a 360-degree posture, ready to fire outward in all directions.

Monti and Lybert lay side by side. Troops pulling guard duty could look through the thermal sights of their rifles and see the remaining heat leave the bodies of their fallen comrades. Viewed through infrared goggles, the two corpses slowly eased from a light shade of gray into the same inky black as everything else around them.

There was nowhere for the medevac helicopter to land, so one of the birds lowered a hoist carrying a combat medic, Staff Sergeant Heathe Craig, of the 159th Medical Company. Just hours before, Craig had been on his computer, using an Internet chat service to play peekaboo with his daughter, Leona, who was just thirteen days shy of her first birthday. His wife, Judy, and their four-year-old son, Jonas, had giggled because Craig’s webcam wasn’t functioning properly—to his family, in their off-post apartment close to Wiesbaden, Germany, their husband and father appeared upside down and green.

It was in the middle of that happy interlude that Craig had gotten the call, and now here he was, doing one of his least favorite things in the world: sitting on a Jungle Penetrator, the drill-shaped device lowered from a chopper to extract troops, balancing himself as he descended into hostile territory on the side of a mountain. He’d volunteered to be a flight medic after concluding that being a regular scout medic wasn’t enough: treating cases of athlete’s foot at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, didn’t leave him feeling as if he were really contributing. But this—well, this was terrifying.

Craig was lowered into an opening in the trees, just above a boulder on a steep decline to the west of the mountain ridge. Garner lit a strobe light, and Cunningham, standing on the boulder, grabbed the medic, losing his wedding ring in the process. Over the din of the choppers, Craig tried to reassure everyone that the ordeal was over.

“We’re going to get you guys out of here!” Craig yelled. “Everyone’s going to be okay.”

The plan was for the two wounded men both to be choppered to an aid station on the same helicopter. Bradbury was supposed to get in the hoist first, but he had started bleeding again and was slipping in and out of consciousness, so Derek James was first to be strapped into the seat. Craig tied himself to the Jungle Penetrator, so that he was facing James around the upright metal stem, and twirled his finger as a signal for the chopper crewman to pull them up. Upon lifting off, the Jungle Penetrator swung from the boulder over the steep decline and started spinning around. Craig controlled the oscillations as he’d been trained to do, and the two men were quickly yanked into the bird.

Craig went right back down again for Bradbury. They got him onto the seat and strapped in, but he was going to be tougher to hoist up because of his wound. Craig twirled his finger again. The Jungle Penetrator swung out and started spinning again, and as they got closer to the helicopter, the oscillating increased in speed.

Unable to hold himself upright, Bradbury was leaning back, making it more difficult for Craig to manage the rotation. The chopper crewman tried to pull the two men up as fast as he could, but the Jungle Penetrator suddenly began spinning out of control. As the crewman frantically worked, the hoist’s cable twisted and turned, rubbing against the sharp edge of the chopper’s floor.

Because it was dark, Craig had fastened a small light to his gear. On Hill 2610, Matt Chambers stood and watched the light spin around until it was a blur.

Then the cable snapped. Chambers kept watching as the light stopped spinning into a blur and instead began falling, flying down. Craig and Bradbury plummeted some one hundred feet, onto the western side of the ridge, and landed on rocks.

Oh no, the men thought as they saw it happen. God, no.

Cunningham ran down to where they’d fallen, as did Chambers and Noble. Craig and Bradbury were both unconscious and clearly in bad shape, drawing shallow breaths. Cunningham checked Bradbury for spinal injuries, and Chambers did the same for Craig, as the medevac flew away. Cunningham told Chambers to hand him the emergency flight radio attached to Craig’s gear. “They’re still alive!” he yelled into it. “Get that medevac back here!” There was no response, only static. Because it wasn’t his own radio, Cunningham didn’t know if it was even working, or if the chopper pilots had heard him.

Chambers could barely see anything, but he could feel that Craig was bleeding profusely. He cradled the medic’s head between his legs, trying to hold it and his neck as straight as possible while also making sure that Craig didn’t choke on the blood that seemed to be pouring from his nose. Chambers did the best he could, but ultimately he realized that he couldn’t do much more than provide the dying man with some small measure of comfort. He cursed his own powerlessness as he heard the last breaths issue from Heathe Craig’s mouth.

Hawes came down and tried to help Bradbury, but he was in the same condition as Craig—mortally wounded, being held by a fellow soldier who was unable to do anything to ward off death’s inevitable touch.

Cunningham meanwhile ran up the mountain and told Grzecki to call back to command and tell anyone who would listen to send that medevac back. Noble followed him up the hill.

“They’re dead,” Noble said.

In the operations center at Forward Operating Base Naray, Howard was intensely aware of everything that had gone down on Hill 2610. Four men were dead, and one wounded soldier—Derek James—had been successfully medevacked to the aid station at Naray. Everyone else was accounted for and would likely be okay for the night. Additional food drops were not needed.

Howard went in to his commander’s office. Then he came back out to the operations center.

It was time to cut their losses. Howard had decided it wasn’t worth it to send a helicopter into an area where an insurgent with an RPG could get lucky and inflict yet another tragedy on 3-71 Cav. There would be no more helicopters that night, he said. He made sure to put plans in place for the spent team to safely walk off the mountain the next day.

“Those guys are just going to have to hold up,” he said.

Cunningham, Hawes, and Woods moved the four bodies away from their camp.

As dawn broke, Cunningham saw the look on the faces of his men. He had seen it before: the huge, wide eyes, the result of a lifetime’s worth of horror and loss packed into a few hours. The look of men who’d had some part of themselves taken away forever. The look of men who had been hollowed out.

The next medevac brought in hard plastic stretchers, referred to by troops as “Skedcos.” The bodies were removed from the mountain, as was the four men’s gear. The thirteen surviving members of the kill team walked back down the mountain toward Forward Operating Base Naray.

A few days later, Captain Michael Schmidt and two Cherokee Company platoons air-assaulted into the Gremen Valley. The men of Cherokee Company watched the building where more than a dozen of the enemy lurked. They took grids and called in bombs. Not much was left by the time it was all over.

Also demolished as a result of this engagement was Howard’s village-hopping idea. It was decided that U.S. forces would come back to deal with Bazgal, Kamu, and Mirdesh at a later date. As happened in every military operation, the enemy got a vote.

Still, even with 3-71 Cav reeling now from two major calamities, Nicholson continually reminded Howard of the need to get the Kamdesh PRT established as soon as possible. Winter was guaranteed to be brutal, so they needed to set up the outpost as soon as possible to be prepared for the elements—and to take advantage of when the snows in the passes would keep the enemy away. It had to be done, Nicholson felt, and it had to be done quickly—and so it would be.