Fittingly, a brutal winter descended over Camp Kamdesh. Gooding had made sure the outpost was prepared, and with firewood burning in potbelly stoves that a local man had purchased in Pakistan and hauled across the border, the troops tried to stay warm. By December, three stone barracks had been constructed at the camp, and two more up at Observation Post Warheit.

The different platoons would rotate onto OP Warheit for two weeks at a time. Not long after Keating died, Able Troop’s 2nd Platoon was assigned to the observation post. There, a stray dog made her way into the good graces of Moises Cerezo, the medic who had tried to save Ben Keating and whose hungry soul was grateful for the companionship.

“Dude, we need to give her a bath,” Cerezo said to Sergeant Michael Hendy. “She has fleas.”

“You’re going to freeze her,” Hendy cautioned. It was winter, after all, and the only available water was bone-chilling cold. Nonetheless, the two men gave the puppy a bath in a frigid stream that ran nearby. She whimpered and shook. She looked as if she might die at any moment.

Cerezo had his fleece on, and he picked her up and drew her to his body. He held her tightly like that for more than an hour. Her shakes eventually lessened into shivers, which soon calmed to nothing. She began playing with Cerezo. He named her Kelly, but everyone else called her Cali. Cerezo slept the first few nights with her in his bunk, zipped in behind the safety of the mosquito netting that kept out the freaky insects that were always dropping on soldiers at night—immense spiders, glow-in-the-dark centipedes, creatures seemingly from another, horrifying dimension.

Then one night Cerezo saw a flea on his fleece, and that was it for his bunkmate. It was too late, however: fleas had infested the barracks at Observation Post Warheit, leaving some soldiers, including Adam Sears, so badly bitten that they looked as if they had chicken pox. There simply weren’t enough flea collars to go around.

Amid subzero temperatures, punishing mountaintop winds, and three feet of snow, Cali’s bugs had ruined the only warm and comfortable spot in Cerezo’s world: his sleeping bag, which, needless to say, he couldn’t wash anywhere. Cali would come into the barracks in the middle of the night, pushing the door open and causing an already cold room to turn into a meat locker.

One morning, Sears awoke to find that the fire in the furnace had gone out. As he grabbed the ax to split some of the chopped firewood, his hand landed in a pile of feces that Cali had deposited on the ax handle. It was the final straw; he snatched up his M16 rifle and chased Cali all over the post. He fired at her, grazing her neck, but she got away, and finally Sears gave up. “I guess it learned its lesson,” he said to himself. Sears felt better, at any rate. Cali soon rejoined her new “owners,” acting as if nothing had happened, as if Sears hadn’t just tried to kill her.

They tried to pass the time constructively. Sergeant Michael Hendy had received some pepperoni in a care package, and he had the bright idea of trying to make pizzas at the observation post, using locally baked flatbread and some tomato sauce the men had bought from the ANA. An interpreter helped the sergeant acquire onions, peppers, and two softball-sized wheels of cheese. Eating dairy up there seemed like a questionable call to some—too many of their fellow troops had sampled the local cheese or milk and ended up suffering a flulike reaction that wrung out their insides—but Hendy was convinced it was worth the risk. Pizza needed cheese, he insisted. Ultimately the question became moot when the wheels were opened and found to be teeming with maggots. Hendy went ahead with the rest of it anyway—the bread, onions, peppers, pepperoni, and tomato sauce. Nick Anderson thought it tasted funny; he looked at the tomato sauce jar and discovered it was two years past its sell-by date. Hendy kept eating.

The winter isolated the men at Combat Outpost Kamdesh and Observation Post Warheit not only from the U.S. Army writ large, but from one another. Anderson bought a goat for a hundred U.S. dollars and asked the ANA cook to prepare it for 2nd Platoon; the result was a crappy stew made of joints and tendons, while the Afghan soldiers kept the good stuff for themselves.

Anderson didn’t make that mistake again. He used his own hunting knife to slaughter the next goat, then butchered it himself, dressing it like a deer. Hendy cooked it up after other troops fetched firewood and prepped the meat. This exercise would be enjoyably repeated, both for the sake of dinner and to kill time. In the late afternoon, Anderson would buy a goat from some locals; each one cost between sixty and a hundred U.S. dollars, depending on the seller, which interpreter Anderson had with him, and whether or not the purchase had been arranged ahead of time. They would name each goat—one was Spicoli, after the stoner surfer in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and another was Baba Ganush, the derisive nickname given to a particular insurgent whom Special Forces had targeted—and then take pictures of themselves with their pending dinner. Tied up at the observation post, each goat got one night—and only one—to bleat.

Scene 1: Spicoli and Staff Sergeant Nick Anderson. (Photo courtesy of Nick Anderson)

Scene 2: Staff Sergeants Nick Anderson and Adam Sears and, on the makeshift grill made from a HESCO basket, Spicoli. Troops melted the fat in the canteen cup to pour over the meat. (Photo courtesy of Nick Anderson)

The enemy had all but disappeared, a seasonal occurrence due to the unforgiving elements. It was assumed that the insurgents had gone to Pakistan, but no one really knew. On December 16, Army Master Sergeant Terry Best, forty-nine, arrived at the Kamdesh outpost by helicopter with the platoon of Afghan National Army soldiers he was in charge of training. The Afghan troops hailed from Kabul, the theory being that sending ANA troops into regions other than their own would discourage the formation of militias with local elders or fighters of a common heritage, ensuring a certain remove that would, it was hoped, allow for a greater sense of objectivity in their military operations. The drawback was that the newcomers would generally be unfamiliar with the local environment and local power brokers, as well as lacking, often, any linguistic and tribal affinity with the local populace.

In this instance, things went sour immediately. The ANA’s Afghan commander started regularly smoking hashish. He also availed himself of pharmaceuticals provided by the ANA medic, as evidenced by the used syringes that Best would find during his periodic walkthroughs of the ANA barracks, which were often redolent with the sweet, skunky stench of hash. When Best told Gooding about the problem, the Able Troop leader couldn’t have been less surprised. His own experience with ANA soldiers so far was that whenever they joined Americans on missions, at the first sign of danger, they would turn and flee. To Gooding, the idea of Best’s foot-patrolling local villages along with eight such Afghan troops—even with the assistance of his staff, Sergeants Buddy Hughie and Chris Henderson of the Oklahoma Army National Guard—seemed downright nuts. Many U.S. soldiers viewed the assignment to serve as an embedded tactical trainer, or ETT, as a sort of punishment, and few wanted to embed with the ANA and become such a naked target for the enemy.

Best contacted the office of the Afghan minister of defense to report the ANA commander’s drug use, and officials at the ministry advised him to inventory the unit’s medical kit to establish proof. Best did so with the support of First Sergeant Qadar, a competent ANA soldier. His investigation was hardly cheered by some of the ANA troops, two of whom came forward to make a not-so-veiled threat: “Don’t fuck with our commander, or you won’t be protected,” one told Best. Afghanistan was already a haze of switching allegiances and uncertain allies; now two Afghan soldiers whom Best was training were telling him that not only might they not be there in the field for him if he needed them, but they might even willingly allow him to be harmed by others. Qadar had the two yanked out of the company and sent back to ANA headquarters. Confronted with evidence of the ANA commander’s drug use, the Afghan Ministry of Defense quickly made the decision to pull both him and the medic who’d been supplying him out of Combat Outpost Kamdesh.

Best had a much more positive impression of the next ANA commander, Shamsullah Khan, who made it clear that he believed his troops needed to be out in the field, protecting their country. Best also liked most of his Afghan trainees; he had cause to be grateful to First Sergeant Qadar yet again after Qadar saved his life by apprehending some insurgents who were planning an attack on him. But his favorite of all was a soldier named Adel, who was an expert at clearing caves and scaling mountains—and a good cook, too.

Among his own men, Best was closest to Buddy Hughie. Hughie had just returned from leave in South Carolina, where his wife, Alexis, had given birth to their first child, a son named Cooper. A smiling and energetic presence, Hughie hailed from Poteau, Oklahoma, where he was active in his local Baptist church. Before he turned two, Buddy, along with his baby sister, Jenny, had been adopted by their grandparents, Mema and Papa, who raised them. With no more than fleeting memories of their on again/off again mother, Buddy Hughie had always protected his sister as if the same unknown evil forces might at any moment snatch her away, too.

Helping people seemed to come naturally to Buddy Hughie, first as an Oklahoma National Guardsman, then as a medic, then as a trainer of Afghan soldiers. He was officially Best’s gunner, but for all intents and purposes, he’d assumed the role of his second in command, a de facto opening ever since Best’s actual second in command had started refusing to participate in combat missions—once even unilaterally calling for a cease-fire in the middle of a firefight. (He attributed his pacifism to his adherence to the teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; why, in that case, he’d joined the military in the first place remained a bit of a mystery.) The reluctant officer also rebuffed a request from Gooding to join Able Troop on a mission, then later complained to Gooding about the living quarters not being up to snuff. Gooding asked his higher-ups if that officer could be relieved. He was, but when no replacement was offered, Hughie ended up doing the work instead.

On December 15, at Bagram, Governor Nuristani met with the commander of the 10th Mountain Division, Major General Benjamin Freakley, to tell him about the establishment of the Eastern Nuristan Security Shura. Its members, forty-five elders from villages scattered throughout Kamdesh District and Barg-e-Matal District to its north, were to meet regularly and confer on how to keep the region safe. The elders would be paid and considered an official body, in charge of development projects and the like. Nuristani wanted the Security Shura sessions, rather than the Kamdesh outpost, to be the place where locals would take their social, political, and security problems and concerns.

The governor had previously raised some eyebrows among American officers by publicly calling for a U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. Nuristani explained to Freakley that he needed to establish credibility so he could initiate direct discussions with some of the more radical elements within Nuristan Province. If the Security Shura was a success, it would demonstrate that the Nuristani people supported Karzai’s government, and that the region was capable of providing its own security—and once those conditions were met, then the United States would be able to leave. Wasn’t that what they all wanted?

Freakley got it, as did Colonel Nicholson. Some of Nicholson’s troops with 1-32 Infantry had just scored a victory in an area of Nuristan that had been harboring insurgents—and they had done it without firing a single shot. The villagers had invited the Americans in for a shura. After conferring with Nicholson, Lieutenant Colonel Cavoli and his men had accepted. The Americans made their case, and the villagers debated among themselves and ultimately voted to expel the insurgents. Ideally, the shura could work as a way of separating the enemy from the people, through social pressure and argument, not bullets.

Governor Nuristani had brought in a controversial local mullah named Fazal Ahad to help guide the Security Shura. When 3-71 Cav first deployed to the region, ten months before, Ahad was on Captain Ross Berkoff’s “kill/capture” list. Until recently, he had been the deputy to Mawlawi Afzal, the man who’d once headed the Dawlat, or Islamic Revolutionary State of Afghanistan, which was recognized only by Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Afzal was thought to have some unsavory connections, and Fazal Ahad was his protégé. Nuristani’s idea was that Ahad could work on both sides of the fence. He certainly had sway with the locals.

If the Security Shura was Governor Nuristani’s baby, 3-71 Cav helped with child support. The squadron funded gas and supplies so the shura members did not have to pay out of pocket to travel to the meetings, which were held in the community mosques of villages and hamlets throughout the province. The Americans also promoted the Security Shura through Radio Naray and other information operations. Beyond that, however, 3-71 Cav did not get involved. If the locals ever started thinking that the shura was an American creation, its credibility among them would be contaminated.

On Christmas Day, the Kamdesh Valley was judged to be secure enough that senior officers could drop in on Black Hawks with “Christmas chow” to boost the troops’ morale. At Combat Outpost Kamdesh, the repast consisted of two military coolers full of cold, holiday-themed foodstuffs: frozen and tasteless canned turkey, pulpy mashed potatoes, coagulated gravy, and the like. The men of 2nd Platoon laughed at the idea of that menu and dug in to hot steaks, onions, and mashed potatoes they’d purchased and prepared on their own. For this special occasion, Anderson had gotten far more ambitious than usual: instead of a goat, 2nd Platoon had bought a cow. He and his fellow happy warriors butchered the beast, packed the meat in bags, and stored their food in a wheelbarrow that they covered with snow.

With the shura process begun, 3-71 Cav turned to overtly pushing an Afghan government program called PTS, which stood for “Programme Tahkim Sulh”30 in Dari and “Peace Through Strength” in English. President Karzai had established PTS in May 2005, under the auspices of the lofty-sounding Afghanistan National Independent Peace and Reconciliation Commission, in an attempt first to get insurgents to renounce their opposition and then to reintegrate them peacefully by giving them some material benefits—in other words, to co-opt them.31

This proved tough going throughout the rest of the country as well as in Nuristan. In December, Governor Nuristani fired Gul Mohammed Khan, the popular district administrator for Kamdesh, and replaced him with a man named Anayatullah. On December 28, Anayatullah met with the Americans and gave them the bad news: village elders throughout Kamdesh were skeptical about the outreach program. Nuristanis found it difficult to believe that anyone whom the Americans believed to be under enemy influence would be either welcomed at an Army base or, more significantly, permitted to leave it again.

Skepticism was far from exclusive to the locals. Many American experts were uncomfortable about the fact that so much of the effort to bring peace to the region now rested on the shoulders of Fazal Ahad, who they believed was motivated only by the desire to get his hands on development dollars. Adam Boulio in particular viewed him as a shady character: Ahad simply isn’t our friend, he thought. His speeches in the shura meetings often seemed to contradict and counter American aims, and Boulio believed that Ahad’s influence actually turned some neutral elders against the United States and the Afghan government.

The soldiers of Able Troop spent the winter months trying to make inroads among the villagers of Kamdesh, distributing bags of rice, beans, and flour as well as teacher and student kits. Officers at Combat Outpost Kamdesh were even asked to help facilitate a visit by Kushtozi elders to Kamdesh Village, to help broker peace between the warring communities of the Kushtozis and the Kom.

By now, 3-71 Cav had been in Afghanistan for just over a year. The troops were spent and demoralized and still in mourning for their lost comrades. But at least they could console themselves with the knowledge that their deployment was almost over. To prepare for the redeployment back to Fort Drum, several hundred soldiers from across the 3rd Brigade—including a couple of dozen from 3-71 Cav—had already started moving back to the United States via Kuwait and Kyrgyzstan. A few had even spent a couple of nights back home with their families.

Gooding, for his part, had been called to Forward Operating Base Naray for a commanders’ huddle to plan for postdeployment training at Fort Drum. It was the first time all of the commanders had been together since they pushed out of Forward Operating Base Salerno in March 2006, and their reunion had a celebratory air.

And why not? They were getting the hell out of Dodge. Berkoff had purchased a plane ticket and booked a week’s vacation in Cancún with some college friends. He’d given his counterpart in the 82nd Airborne—which was supposed to replace 3-71 Cav at Naray—his DVDs, his books, and even his bunk. (Berkoff had moved from his little hooch to a tent near the landing zone.)

In the middle of the night on January 22, 2007, the staff and commanders were told to report to Howard’s office. As he watched Captain Frank Brooks get up from his cot and head to the lieutenant colonel’s office, Erik Jorgensen worried that they must have had a KIA. But no artillery was firing, Jorgensen noticed. And no one was out. Maybe there was an urgent mission of some sort? What was going on?

This was what was going on: the political dominoes had fallen, and as always, the joes in the field were the ones knocked facedown on the floor by the last game tile.

Two and a half months before, back in the United States, the Republicans had taken what President Bush referred to as “a thumpin’ ” in the November 2006 elections, with the downward trajectory of the war in Iraq being seen as one of the major contributing factors in the Democrats’ recapturing of the House and Senate. A head had to roll, and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld offered his up. The brand-new secretary of defense would be Robert Gates, the president of Texas A&M University and former deputy national security adviser and director of the CIA for Bush’s father, President George H. W. Bush.

A few days before the leaders of 3-71 Cav were summoned in the middle of the night to meet with Lieutenant Colonel Howard, Gates had visited Afghanistan and met with commanders on the ground. Lieutenant General Karl Eikenberry, the outgoing commander of the U.S. Combined Forces Command Afghanistan,32 requested that the tours of thirty-two hundred soldiers from the 3rd Brigade—including all four hundred troops from 3-71 Cav—be extended for up to 120 additional days so that the overlap with the incoming brigade would create a mini “surge” of troops. It wasn’t easy for Eikenberry to ask for the extension, but it was his only option, as the war in Iraq remained the Bush administration’s main effort. Gates agreed.

“Although it is going to be a violent spring and we’re going to have violence into the summer, I’m absolutely confident that we will be able to dominate,” Eikenberry declared.

So there they all were, in Howard’s office: Gooding, Brooks, Schmidt, Stambersky, Berkoff, Sutton, and others. Howard got to it quickly.

“Our deployment has been extended four months,” Howard told them. “The new secretary of defense wants and needs more troops here, and there are no others—we’re the only combat brigade that’s ready, and all the other units are committed to Iraq.”

Gooding began trembling. It was the same feeling he had when he lost a soldier. He was certain that this decision would mean at least one of his men would die.

Berkoff later wrote to his friends and family:

No words can describe how I felt when I was shaken out of a cold sleep, only to be told that we’ve been extended another four months. I should have realized something was up when we just received a new shipment of uniforms that were long overdue. I’m sure the Defense Sec. Gates, who’s been in his office for all of two weeks and came out here to visit, listened to some NATO general say that we needed more troops in Afghanistan—and that’s it. The entire 3rd Brigade, and the 10th Mountain HQ, all ordered to remain. We are now calling back hundreds of soldiers who already went home to return to their posts out here. All our equipment that we sent away, it’s coming back, or so we hope. It’s just unreal. God help the man who made this decision when we lose another soldier.… All I can say is that I’m sorry for what we’re putting you through. I’ll be home one day, and if no one else is hiring in the market, I know a few guys here who would make outstanding Bush Administration Protesters for a living.

Captain Brooks returned to his tent with a grim look on his face. He sighed and said, “Someone get all the platoon leaders and platoon sergeants.”

Five minutes later, sleep-deprived and dazed, the Barbarians’ platoon leaders and sergeants heard the news from their commander.

“Listen, guys, there’s no easy way to say this: we’ve been extended another four months,” Brooks told them.

No one spoke; everyone was dumbstruck. Jorgensen was supposed to get married in two months’ time, and Brooks himself two months after that. Neither would be able to make his own ceremony.

Gooding called Combat Outpost Kamdesh and asked for First Sergeant Todd Yerger. He broke the news to him, though Yerger had already seen some emails about it. The first sergeant huddled the troops together. He told them he had good news and bad news.

“The bad news is you aren’t going home,” Yerger said. “The good news is you’ll get paid an extra thousand bucks a month.”

The men were devastated. Some began to weep.

Back at Naray, Jorgensen sat on his cot and let it all sink in. He pulled on his shoes and walked out toward the phones to call his fiancée, Sheena, and his parents. Turning the corner, he saw a line for the phone that would take hours. So much for that.

He went back to the troop command post and hopped onto the computer to email Sheena and his parents:

I really don’t how to say this, so I’m just going to come out and say it.… We’ve been extended. We’re not coming back until June now. I think the most obvious thing is that the wedding will have to be postponed. This info is about three hours old right now, so I don’t have a lot of answers. Normally I’d call for something this important, but the phone line has 150 people in it right now and it’s only getting longer. I really don’t know what to say right now, we’re all still in shock. I’ve got to go now and talk to my soldiers, a lot of them aren’t taking it well. I love you guys.

—Erik

Jorgensen’s captain, Brooks, was one of those soldiers not taking it so well. Right before Lieutenant Colonel Fenty’s helicopter went down, Brooks had been talking to his first sergeant about how he was convinced—had always been convinced—that his girlfriend, Meridith, was “the one.” After Fenty and the other nine men died and Brooks got off the mountain, he found the first phone he could use and called her. “I can’t tell you what’s going on, but we had a pretty bad event happen, and it’s made me realize—will you marry me?” he asked her. “Yes,” she said. They soon picked a date: June 9, 2007.

Now Brooks was calling her again, this time to tell her that his deployment had been extended and they would have to postpone their wedding. She’d already moved to upstate New York and set up an apartment, believing he’d be there in February. She was distraught, and they both wept. “I don’t believe you,” she cried. “Why is this happening?”

The move was a surprise and not a surprise. Speculation about an extension had been swirling for weeks, but the anxious troops of 3-71 Cav had been told not to worry. Major General Freakley had visited Forward Operating Base Naray on Christmas Day and given them a short speech: “Gentlemen, I know there are a lot of rumors out there about us getting extended,” Freakley said. “Let me be the first to tell you: we will all go home in February!”

He was half right. Freakley himself did go home in February. The men of 3-71 Cav had to stay until June.

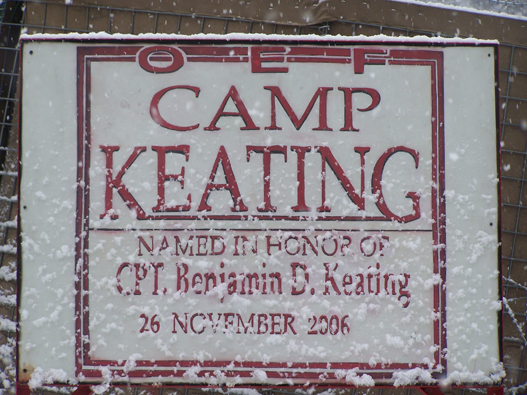

The priest had been FOB hopping, flying from base to outpost, tending to the soldiers’ spiritual needs as best he could. It was hardly an ideal situation for either the clergyman or his flock, but “ideal” as a concept had been tossed out the window the first day American troops set foot in Afghanistan. Now he was here on a particularly chilly day for the renaming of this outpost in the Kamdesh Valley. It would henceforth be known as Combat Outpost Keating.

“We ask your blessing on the dedication of this camp in the memory of First Lieutenant Benjamin D. Keating, a risen warrior of Able Seven-Three-One,” the chaplain prayed during the ceremony. Of course, the squadron wasn’t 7-31, it was 3-71, but the chaplain repeated his mistake: “Thank you for the service and sacrifice of Able Seven-Three-One,” he said.

What would Ben Keating have made of such an error? He would likely have rolled his eyes and had a laugh at the Army’s expense. He had given his life for the Army, and the Army couldn’t even get the name of his squadron right.

Gooding had been mired in his own misery after Keating’s death; it had taken him a month or so to snap out of it. After he did, having recognized the pit of despair in which he’d been trapped, he was thankful that his depression hadn’t come during fighting season. During the ceremony, he tried to keep his tone positive. He unveiled the wooden sign identifying the camp as Combat Outpost Keating—the wood had been cut by Billy Stalnaker, the design was by Specialist Jeremiah “Jeb” Ridgeway—and said that Keating would have been honored.

The Kamdesh outpost was named in honor of First Lieutenant Ben Keating, promoted posthumously. (Photo courtesy of Matt Netzel)

It was a rough winter for Captain Matt Gooding. (Photo courtesy of Matt Netzel)

Tens of thousands of miles away, in Shapleigh, Maine, Ben Keating’s parents, Ken and Beth, were ambivalent about the dedication. They understood the desire of the men of 3-71 Cav to honor their son and, perhaps, to lift their own spirits as they faced the depths of winter at Kamdesh. However, the Keatings had no illusion that the camp would be a permanent fixture in the landscape of Nuristan. (Gooding had mulled over this issue, too.) The monument for their son would be, one way or another, short-lived. The next company would have no idea who Ben Keating had been. New leadership might decide to abandon Combat Outpost Keating altogether. And the site, because of its vulnerability, might be overrun. Indeed, it was the location of the outpost that seemed to trouble Beth Keating the most. She didn’t like the notion of her son’s memorial standing in such a horribly dangerous part of the world. She was touched that the men Ben had served with had felt so strongly about him, and so affectionate toward him, that they wanted to honor him, and she knew there were limits to what they could do. But it was almost as if someone had decided to rename a sinking ship after her beloved boy just as it slipped below the waves.