Nothing happened, and then everything happened at once.

Per Lieutenant Meyer’s orders, Ryan Fritsche led a team out to set up an observation post from which they would watch over the valley. They would cross the bridge, make their way east on the road in the direction of Forward Operating Base Naray, wait for their cue, and then slog up the southern mountain.

“An OP site?” said Wilson, always questioning. “We don’t have any cover for it.”

“Let’s go,” Fritsche said. “We’re going to push down the road.”

Fritsche, Wilson, Private Barba, and their SAW gunner and rifleman, Privates First Class Nic Barnes and James Stevenson, walked over the bridge and then continued on a couple of hundred yards to the east, where, near a large boulder, they came upon two American snipers, Staff Sergeant Bryan Morrow and Specialist Matthew White. The sun was oppressively beating down upon them all, and Fritsche told his men to drop their packs and helmets; the additional weight was too much, he said.

“We saw two guys with AKs run up the hill,” Morrow reported. The snipers had been scouting ahead for the rest of the company, and as they were moving up the side of the mountain, they’d glimpsed a young male Nuristani, age eighteen or so, holding a rifle, along with a boy of about twelve, both running away from them.

Why would anyone with a weapon run away? wondered Wilson. He thought of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War and the concept of a baited ambush. The Chinese military strategist had described the tactic centuries before: “By holding out baits, he keeps him on the march; then with a body of picked men he lies in wait for him.”

“We’re going to recon the patrol base,” Morrow said, meaning they were going to scout out a place for an observation post.

Fritsche turned to his men, Wilson and Barnes, and explained the mission, adding that they would walk in single file because of the steep climb.

“We’re not supposed to go until we get word,” Wilson reminded him.

But Fritsche shrugged off Wilson’s protest. Barba and Stevenson stayed back at the rock while the others started up the hill. White took point, followed by his fellow sniper, Morrow. Fritsche, Wilson, and Barnes came next. After climbing about a hundred yards, they saw the two locals in the distance. All five men broke from their single file and spread out on the hill.

“We’re being led into an ambush!” Wilson yelled. “Stop following the kid!”

“Shut up!” Fritsche said through clenched teeth.

“Stick with me,” Wilson said to Barnes. “This is bad.”

Barnes said he would. Wilson was his team leader as well as his friend. And he shared Wilson’s concerns about Fritsche’s lack of experience in the field.

Bostick and his team finished up with the shura and left the village, crossing the bridge back to the road to Kamu. On hearing that Fritsche and the snipers were pursuing suspected insurgents up the mountain, Bostick pulled aside the medic, Fortner, and advised him, “Get ready.” The ANA troops who’d accompanied them on this operation thought they saw something odd going on at a house back across the bridge, one that had previously been used as a staging ground for an RPG attack. After Bostick gave them the okay to run back and check it out, they recrossed the Landay-Sin River and went into the house. Bostick now turned to his men and said, “Guys, let’s get off the road.” He, Johnson, Lape, Sultan, and the others headed up into the sloping woods. Bostick was just a few steps up the hill when he stopped.

“Wait,” he said.

Pausing, they listened to the radio: lots of enemy chatter. Sultan looked north, back across the river, to the hamlet of Saret Koleh. He saw a villager pick up her child and start running.

Bostick had instructed the ANA troops to rejoin the group once they’d checked out the house on the other side of the bridge, but after exiting the home—where they hadn’t found anything—they instead continued walking eastward, away from the bridge and toward a second home across the river.

Up on the southern mountain, Fritsche, Wilson, and Barnes followed the snipers, Morrow and White, as quickly as they could up the steep incline. They came into an open area. It was still and silent—until enemy guns began firing at them from some one hundred yards farther up the mountain. Bullets whizzed by, making a snapping sound. At first the U.S. soldiers weren’t sure which way to run, forward or backward, but then they swiftly pulled back and took cover behind some trees down the hill.

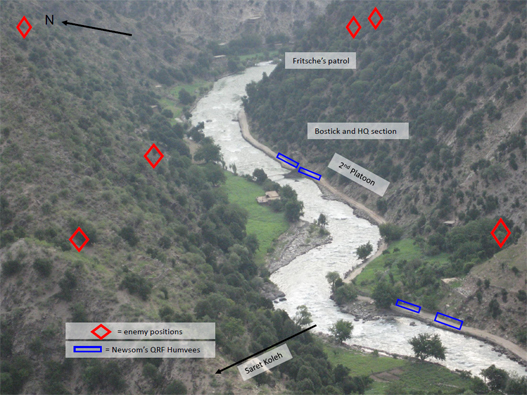

Roller’s view of the eastern side of Saret Koleh. (Photo courtesy of Dave Roller)

Insurgent fire aimed at Tom Bostick and Headquarters Platoon now also began exploding from the hills above—the same mountain that Fritsche’s patrol was on, but farther west. Bullets splashed into the Landay-Sin River.

The ANA troops ran back across the bridge toward the road, returning fire with their AK-47s and RPGs as they went. One ANA soldier fell, shot in the leg: it was Habibullah, on whose head Newsom had broken his hand weeks earlier. Since then, the Afghan had developed trusting relationships with many of the Americans. He’d been hit in the thigh; Rob Fortner met him and hustled him to safety in the trees. Nearby, Bostick, Johnson, Lape, and Sultan took cover in the woods behind some boulders.

Farther to the west on the southern mountain, from his observation post high in the hills, Dave Roller had been watching Bostick and his men and trying to figure out what the ANA troops were looking for. The insurgents now answered that question, as 1st Platoon, too, was hit by a shower of small-arms fire and RPGs.

The enemy had the high ground, attacking from the mountains above the platoon’s position and surrounding it from left to right, 270 degrees. Specialist Tommy Alford got his M240B machine gun, ran to the southern edge of 1st Platoon’s position, and laid down a streak of bullets. Then he realized that shots were coming from the east as well, so he began returning fire in that direction. A bullet hit him. Blood gushed from his neck. Alford kept firing until he collapsed.

“I’m hit!” he screamed. “Oh my God, I’m hit!”

Private First Class Miles Foltz grabbed his wounded comrade and pulled him behind a large rock, where he began administering first aid. The bullet had torn through the right side of Alford’s jaw and exited out his neck. Foltz bandaged up the exit wound; the stream of blood was forceful, as if springing from a bottomless source.

Roller, busy switching among the three radios he had, yelled for someone to pick up Alford’s machine gun. Every second spent on something other than coordinating bomb drops would be, for Roller, a second wasted. Specialist Eric Cramer responded to the lieutenant’s order, snatching up the M240B, and then he and Foltz took turns trying to save Alford’s life and trying to end the lives of a few insurgents with the machine gun. At one point, when Foltz replaced Alford’s saturated bandage, the blood began spilling out again.

“Oh, shit,” Foltz said. He plugged the hole in Alford’s neck with his hand, then rebandaged the wound and attempted to calm down his injured friend, talking to him as if he were confident that everything was going to be just fine.

Crouched behind a rock, Ryan Fritsche tried to reach the rest of Bulldog Troop to report his patrol’s position and give its coordinates, but discovered that his radio wasn’t working properly; it kept cutting in and out. Wilson, who had been on guard a short distance away from the group, came back and offered to tinker with it, but once again, Fritsche turned him down.

Not long after that, word came crackling over the radio that Alford had been shot in the neck. All units were ordered to stay where they were until he’d been medevacked out.

Apaches now flew into the valley, and as they swept through, Fritsche, Morrow, White, Barnes, and Wilson could hear the enemy, just a few hundred yards above them, firing at the U.S. helicopters.

Tom Bostick and his patrol were farther down the mountain, to the west, closer to the road. The captain directed Kenny Johnson, his fire-support officer, to get the mortars firing and have them hit the ridge above them to the southwest, where the enemy now had Dave Roller and his men pinned down. They needed to beat back the insurgents so they could get a medevac in there. Johnson called it in, and seconds later, there was a faint boom off in the distance.

“That’s it?” asked Bostick. The mortars hadn’t landed even remotely close to where they needed to go.

The captain grabbed the radio from Sultan. “Why isn’t there fucking mortar fire?” he bellowed. “What the fuck is going on? Why don’t I have mortars?!”

He was told that the mortars were being adjusted; apparently the mortarmen were resetting the base plate, which had become unbalanced.

“Fuck this,” Bostick said, dropping the radio. He turned to Johnson and gave him an order: “Fix this.”

They needed the medevac to drop a Jungle Penetrator up at Roller’s observation post so that Alford could be strapped onto it, pulled up into the chopper, and whisked away—now.

Roller’s voice came over the radio: “Alford’s going to die,” he announced. “He got shot in the fucking neck—we need a medevac now, or he’s gone.”

Bostick turned to Johnson and urged him to encourage their friends in the medevac to hurry up and get into the valley. “Tell those pussies to stop being fucking pussies and get out here,” he said.

Back at Combat Outpost Kamu, Alex Newsom was still impatient to join the fight, but as the leader of the quick reaction force, he couldn’t take any of the men from 3rd Platoon into battle before the first American casualty was reported. Whenever shots were fired, he would radio Bostick to ask if he wanted the QRF to ride in, but he was repeatedly told to hold off. Then word came in of Alford’s wound, and the four Humvees in the QRF hit the gas, with Faulkenberry’s truck in the lead.

Newsom’s team made radio contact with Roller’s unit, and just as the QRF pushed east and passed beneath 1st Platoon’s position up in the hills, its Humvees took fire from across the river to the north. Faulkenberry’s gunner, Private First Class Michael Del Sarto, countered with his M240 machine gun, as did Newsom with both his M240 and his MK19 automatic grenade launcher. At the “casualty collection point”—a just-in-case prearranged spot on the road—3rd Platoon put on the brakes. Newsom and his men jumped out and began offloading boxes of water and ammo for the troops of 2nd Platoon, who had been moving east on the road when enemy fire began pummeling them from all sides, causing them to scatter into the hills to seek shelter and shoot back. Fortner, the medic from 2nd Platoon, was treating the wounded with little regard for his own safety. He sprinted from the injured ANA soldier to a mortarman who’d been shot, then ran down to help two others who’d been sprayed with shrapnel from an RPG. Calls came in that the mortarman wasn’t looking good, so Fortner headed back up the hill to check on him; in the minute or two it took him to get there, he felt as if every enemy fighter in the valley was shooting at him personally. The intimidating cracks of insurgents’ bullets terrified him as he scurried up the steep embankment; the ground kept slipping out from under him, and rounds that only barely missed him kicked up debris on all sides. I’m not going to make it through this day alive, Fortner thought to himself—and in that moment, he achieved a sort of clarity that caused the hyperactivity around him to slow down and made his task seem easier. He regained his footing and got up the rest of the hill. And then, after he’d done what he could about the mortarman’s internal bleeding, something that felt like a baseball bat hit his right elbow, spinning him 180 degrees and dropping him to the ground. His right shoulder had caught a bullet, which he quickly slid out of the wound, patching a piece of gauze into the hole. A bleeding Fortner then helped get the other four wounded men—Habibullah and Privates First Class Scott Craig, Stan Trapyline, and José Rodriguez—to Newsom’s Humvees. The medic himself refused to be evacuated. As the QRF pulled out, Fortner stood and yelled at the insurgents in the mountains. “You fucking pussies!” he screamed. “Your bullets feel like bee stings! I’m going to fuck all of you up!” He later wouldn’t remember doing it.

Newsom’s team drove these first four casualties to a nearby cornfield—maybe twenty-five feet by twenty-five feet—that the lieutenant had decided would serve as a landing zone. From there, a helicopter took them out. Bostick had told Newsom to return to Kamu afterward, but he didn’t do it. It was the first time in his career he’d ever disobeyed a direct order. He wanted to stay close to the fight.

Up on the mountain with 1st Platoon, Roller glanced over at Foltz, who was tending to Alford’s wounds. Foltz was a touch nerdy, Roller thought, but boy, was he a cool character at that moment. Collected and assured, Foltz gave him a thumbs-up. Roller looked at Alford. He was clearly in a daze, having lost a lot of blood, but he somehow managed to give his lieutenant a thumbs-up as well.

A medevac buzzed into the valley, drawing a cacophony of incoming fire. “Red-One,” the pilot radioed to Roller, “we cannot land.” Nor would the chopper be able to hover long enough to hoist Alford up on a Jungle Penetrator, he said; it was still too hot in the valley. Roller and the others on the ground would have to get more of the enemy cleared out first. The medevac turned around.

Roller gave the Apache pilots targeting grids so they could bomb and fire upon the insurgents. Twice, the Apaches flew so close that he could see right into their cockpits. It was still not enough. Roller and his Air Force communications officer also tried to get the French and Belgian pilots of some nearby Mirages to offer air support. Although English is the standard language for NATO, it took them all a while—too long—to overcome the considerable language barrier; one of the pilots even read back the instructions for a bomb drop and identified 1st Platoon’s position as the target. That mistake was quickly corrected by Roller and, several miles away, by Kolenda’s Air Force liaison. Kolenda, infuriated, demanded that Colonel Charles “Chip” Preysler, commander of the 173rd Airborne, see to it that in the future, his men be sent only U.S. aircraft.

On this day, though, the French bombs eventually began to hit their targets, as did the U.S. ordnance, and a credible path was cleared for the medevac. Under heavy fire as tracer rounds reached out from enemy positions throughout the valley, the Black Hawk lowered a medic, Staff Sergeant Peter Rohrs, on a Jungle Penetrator. To the men watching, it seemed nothing short of miraculous that Rohrs made it to the ground. He unhooked his cable and ran to Alford, whom he treated with an IV and more bandages. Rohrs was concerned not only about the specialist’s neck wound itself but also about making it worse by hoisting him sitting upright on the Jungle Penetrator—but there wasn’t much time to contemplate. He put a neck brace on the injured soldier; that would have to suffice. Amid furious incoming fire, the two men, wrapped around the rescue device, were hoisted into the belly of the Black Hawk. After a perilous rise, Rohrs and Alford entered the medevac, which then turned and sped out of the valley. As the enemy barrage continued, one of the Apache pilots got on the radio: “Hey, guys, I’m hit,” he said. “I’m heading back.”

Up with Fritsche’s patrol, Morrow had seen the shot that hit the Apache; ominously, it had come from right above their position.

Wilson was worried that the pilots might mistake them for insurgents. He expressed his concern to Fritsche, who tried to reassure him that their position had been relayed to the Apaches. Either way, Wilson found it terrifying to see the Apache pilots pointing their 30-millimeter chain guns at—or at least near—them, especially when the patrol’s radio wasn’t working reliably. It was easy to imagine, he thought, how friendly-fire incidents could happen. Before the radio died once and for all, Fritsche got the call that Bulldog Troop was waiting for him and his team to come down the mountain, and they needed to move now.

As the fight lulled for about ninety minutes, Bostick, Johnson, and Lape walked down toward the road, leaving Sultan behind to cover them. The trio stopped next to two big boulders. Lape climbed up onto a rock to better position his radio. He lit a cigarette. Bostick meanwhile got on the radio to try to find out why the mortars had been so ineffective at helping out Roller and his men; multitasking while doing that, he also directed his platoons into position and cracked a few jokes to relieve the tension. Sultan, who had been providing cover from some yards up the hill, now sucked up an MRE pack. He was facing downhill, toward the north, watching Bostick, Johnson, and Lape. Beyond them was the road, and beyond that the Landay-Sin River, then more mountains.

Without any warning, an RPG exploded between Sultan’s position and Bostick’s. None of the men was sure which direction it had come from: south, up the hill? north, across the road? Sultan grabbed his rifle and ran downhill. Believing the RPG had been launched from somewhere behind him, uphill to the south, he ducked under a holly oak tree, turned around, and slid into a firing position right near Bostick, Johnson, and Lape, by the two large boulders.

Bullets rained down on the rocks. Shrapnel hit Johnson’s chest plate.

“Sir,” Johnson said to Bostick, stating the obvious, “they’re shooting at us.”

“Shoot back,” Bostick told him.

An insurgent sniper fired a rifle shot disturbingly close to their position, which was soon followed by an RPG blast near the same spot. The sniper fired again, closer this time. Another RPG followed. Bostick and his team realized that the sniper was showing the enemy RPG team exactly where they were.

“We’re taking fire, we don’t know where from,” Bostick radioed in. “We’re going to have to move. We need cover, suppressive fire.”

“We should break contact and link up with the rest of Second Platoon,” suggested Johnson. Bostick agreed and prepared to lay down suppressive fire to cover their move. Lape got ready to throw a smoke grenade as Bostick stepped out from behind the boulders and fired his rifle. But then suddenly Johnson lost his footing and began sliding down the steep hill.

“We need cover!” Bostick yelled. “I think they’re coming from the ea——”

At that moment, an RPG came right at them from up on the mountain to the southeast. It exploded and sent off a shock wave that threw all four men into the air.

West of and up the mountain from Bostick’s position, Roller witnessed the RPG explosion and watched as, amid a plume of smoke, Johnson flew downhill some thirty feet, landing near the road.

“Bulldog-Six, Bulldog-Six, where are you?” Roller called on the radio for Bostick. “Bulldog-Six, Bulldog-Six, come in.” There was no response.

Alex Newsom’s call sign was “Bulldog 3-6,” but Roller, worried that something had happened to their captain, didn’t think military protocol conveyed what he needed to express at that moment. “Alex, it’s Dave,” he told Newsom over the radio. “I need you back in the valley.”

Newsom knew that Roller’s call sign was “Bulldog Red-1,” but he followed his friend’s lead. “Okay, Dave,” he said.

As Newsom and his platoon motored into the danger zone from their spot down the road, not far from the casualty collection point, Faulkenberry turned to the lieutenant.

“Can I look for him?” he asked.

“Let’s go,” said Newsom.

They roared back into the fight with guns blazing, picking out enemy positions and obliterating them with their big weapons. Newsom yelled to Specialist Andrew Bluhm, the gunner on the MK19 grenade launcher, “Keep shooting! Keep shooting!”

Bluhm didn’t need to be told twice.

As Fritsche and his patrol worked to get down the mountain, Newsom and the QRF sped by on the road below, heading west toward Tom Bostick. The battle had started up again.

John Wilson was a native of Littleton, Colorado, so he knew mountains, and he had done a lot of trail running. He led the way as the enemy fired on them from the mountain across the river. While the others—Fritsche, Morrow, and White—returned fire, trying to provide cover, Wilson and Nic Barnes would run from behind a tree, dart diagonally down the steep decline of the mountain, then jump behind another tree. From there, Wilson and Barnes would provide cover as the others ran down to where they were. They did that over and over, trading tasks, with each team covering the other so both could make incremental progress—a strategy known as bounding. Enemy bullets rained down on the covering troops, shredding leaves, bark, and everything else in their vicinity, but the enemy’s focus on them meant that the others could crisscross and run down the mountain as well.

The pattern they established had Wilson and Barnes starting their next sprint just before the other three landed safely behind cover. On one relay, Wilson, pausing to hide, looked down and thought he saw tracks on the ground in front of him. He stopped beside a boulder and gingerly walked around it. About twenty feet east of their position, near a dent in the rock wall, three Afghans were looking down the mountain toward the river. Two of them were wearing new ANA battle-dress uniforms and holding AKs. The third looked like an Afghan policeman, complete with police radio and pistol.

Barnes came up on Wilson’s right, Morrow on his left.

“What do we do with these guys?” they whispered to one another.

Morrow and Fritsche weren’t sure who the men were—they could be ANA, they thought—but Wilson and Barnes were convinced they were insurgents. The Afghans were excited, jubilant—not the sort of behavior to be expected from ANA soldiers in the middle of an ambush. Indeed, to Barnes, the Afghans seemed to be laughing as they watched the Americans below them in the valley being attacked, wounded, and killed.

The debate ended when the Americans noticed that one of the Afghans had a black facemask rolled up on his head that he could pull down to obscure his features. Another held a facemask in his hand.

Wilson turned to Barnes. “Fuck these guys,” he said. “Morrow and I will take the two guys on the left,” he whispered, referring to the Afghans. “You aim at that one on the right. Let’s just mow them down.”

Barnes, Morrow, and Wilson fired at their assigned targets. White and Fritsche fired from behind them as well. The three insurgents fell—and for a brief moment, at least, that seemed to be that. The men’s relief quickly dissolved, however, when a fourth insurgent with a facemask popped up from behind a nearby group of rocks and sprayed a full magazine at them from his AK, then took cover again. The Americans were already shielded by trees and boulders, so they hunkered down. Bombs now began dropping from a U.S. aircraft, two five-hundred-pounders that whistled angrily on their way down. They landed dangerously close and interrupted the firefight. Wilson ran to check the rear—there had been, after all, dozens of insurgents shooting at them as they moved. Fritsche took cover next to a rock, returned fire, and began trying to work the ailing radio again; he wanted to call Bostick to make sure the pilots dropping the bombs knew where his squad was.

Wilson, higher up on the hill, could see Fritsche’s shorn, helmetless head poking up above the boulder. He shouted for Fritsche to crouch down even further, but at the very moment the staff sergeant looked up and their eyes locked, the fourth insurgent fired—and the enemy bullet found its target above Ryan Fritsche’s left eyebrow, exploding out the back of his head.

To their west, Jonathan Sultan woke up from the RPG explosion.

He wondered if he was dead. He had seen the explosion, had seen the RPG hit Captain Bostick. He didn’t know where his captain was now.

Sultan could see only out of his right eye; his left was hanging out of its socket. His left hand, which had flash-burned when the RPG detonated, was charred black. He could hear nothing but a loud ringing. Then he could just make out someone—Lape?—shouting, “Run! Run! RUN!”

Sultan managed to stand. A piece of shrapnel roughly the size of a baseball had torn through his left shoulder, ripped through his collarbone, and exited out his back. He started running down the hill. He knew that if he stopped, he would die. He wanted to yell out, “Where are you?” to the men of 2nd Platoon, who he believed were down the mountain, but the word where kept coming out as “wheer.” He stopped for a second. Wheer. Wheer. What was wrong with him? Why couldn’t he talk? He thought, This is it. A sniper’s going to get me. And then he heard, to his left, “Over here, over here, get over here,” and Lape pulled him aside and rushed him down to the casualty collection point.

Johnson watched as Lape escorted Sultan down the hill to cover, near a rock by the river. Half of Sultan’s face was charred; he reminded Johnson of the Batman villain Two-Face.

Dazed, Sultan thought to himself, If I run into the river, I’ll sink. And then he was lying on his back, feeling the cool mist of the Landay-Sin River on his destroyed face.

Morrow checked Fritsche’s pulse. “He’s dead,” the sniper said.

“No shit,” replied Wilson. He’d just seen the back of Fritsche’s head explode. Blood and gray matter lay on the rock behind him. He wasn’t moving. He wasn’t breathing. He wasn’t bleeding.

They were still pinned down by the fourth insurgent, who by now had been joined by several others. Wilson threw a grenade at them, but it took forever to go off.

One thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three, one thousand four, one thousand five, BOOM.

No way had it gotten the insurgent, thought Wilson; he’d had too much time to run away, and the explosive had rolled down the mountain. The sergeant grabbed another grenade. He pulled the pin and let it cook off for two seconds.

One thousand one, one thousand two. Throw. One thousand three, BOOM.

It went off a second and a half early: Got him, Wilson thought. For once, the Americans’ unreliable equipment had worked to their advantage.

“We need to get down the hill,” Morrow said. Soldiers are taught never to leave fellow troops behind on the battlefield, including fallen ones, but Morrow was convinced that any attempt on their part to bring Fritsche’s corpse down the mountain just then would result in even more casualties. Instead, they’d link up with the rest of their company at the bottom and then return for the staff sergeant. That was the plan, anyway. That was what they told themselves as they ran down the mountain.

When Faulkenberry pulled up in his Humvee at the casualty control point by the river, he saw Rob Fortner working on someone whose face was so mushed up and bloody that he couldn’t even tell who it was. It turned out to be Sultan.

“Thank God, it’s the Cavalry,” the medic managed to crack as he heard the trucks pull up. They sounded as if they were bringing hell with them: the QRF troops were firing their machine guns full-auto nonstop, and a grenade launcher was sending thundering explosions one after another against the enemy across the river. “Where’s Captain Bostick at?” Faulkenberry asked Lape and Johnson, who were sitting near Fortner and now looked at him with big doe eyes, shaken up.

They pointed up the hill.

From the road, Faulkenberry could see antennae poking up from the rucksack Johnson and Lape had left behind. He headed up toward the radios and came across a decapitated corpse in a U.S. Army uniform. Flesh was missing from the soldier’s right elbow and right knee, and there were marks from several bullet and shrapnel impacts on his body armor. Faulkenberry opened up the armor to check the nametag:

BOSTICK, it said.

All U.S. troops have unique battle-roster IDs—the first letter of their last names followed by the last four digits of their Social Security numbers—but Faulkenberry didn’t feel the need to pull the list out of his pocket and consult it. He walked down to his Humvee and got on the radio: “Bulldog-Six KIA,” he said. Then he went back up the hill again and began dragging Bostick’s body to the road, pulling him by his arms. One of the arms started to come off, so Faulkenberry dragged him by his other arm and his belt. Newsom came over, and the two of them, horrified by their task but determined to see it through, grasped Bostick under his hips and by his clavicle and, with Staff Sergeant Ben Barnes,38 lifted him into the back of Newsom’s truck.

Back at Forward Operating Base Naray, it was all seeming backward.

The commanders had originally thought the real action would be around the other element of the operation, to the east, in Bazgal. Lieutenant Colonel Kolenda had air-assaulted with a Legion Company platoon to a nearby mountain to watch over that area as Command Sergeant Major Vic Pedraza, Nathan Springer, and their men made their way to the Gawardesh Bridge—a mission they accomplished completely unchallenged.

When they heard about the firefight at Saret Koleh, a number of the officers and men at Gawardesh wanted to drive over there to help out Bulldog Troop; Springer and his .50-caliber gunner, Specialist Josh Kirk, were particularly desperate to push west. But part of the road near the Bazgal Bridge had been washed out and was now impassable, so there was nothing any of them could do beyond listening on the radio. Their feeling of impotence tore them up as they followed the unfolding nightmare.

Word that Bulldog-6 was down struck those back at Forward Operating Base Naray like a thunderbolt. With Kolenda in the field, the operations center at Naray was being run by Sergeant Major Ted Kennedy. Before deployment, Kennedy, Bostick, Joey Hutto, First Sergeant Nuuese Passi, and their wives and children had all gone to Egypt together on vacation. The four men and their families were very close. Major Chris Doneski, who was in the operations center when the tragic news came in, quietly approached Kennedy and asked if he could speak with him. They walked into Kolenda’s office. The major shut the door.

“We lost Tom,” a stunned Doneski said.

Kennedy doubled over. He made his way to a chair and sat down, speechless. Kennedy and Bostick had been Rangers together, and close friends for years.

After a few minutes, Doneski found operations officer Major Darren Fitz Gerald and told him the same news. The three men huddled and talked about what to do next. Dozens of troops were engaged in battle in a dangerous valley, without a commander.

Joey Hutto was scheduled to relieve Bostick at the end of the year anyway, they noted. “We need to get him up there now,” the men agreed.

Hutto happened to be out in the hall just then, looking for Kennedy. The battle had clearly gotten tough, and he wanted to get the big picture, which he knew Kennedy could give him. He was beckoned into Kolenda’s office, where a grim-faced Doneski stood, by himself, waiting for him. Doneski looked at Hutto: he obviously had no idea what had happened to his close friend.

“Hey, Joey,” Doneski said, “I can’t believe I’m telling you this, but Tom’s down. We lost Tom.”

If Hutto’s reaction was less physical than Kennedy’s had been, it was still visible: he looked as if he’d been smacked by a wave that had knocked him back, disorienting him.

Soldiers are trained always to finish the task. In the chaos of battle, they’re not given time to reflect. There is a job to do, and becoming mired in the quicksand of grief can only result in more deaths, greater anguish.

And yet.

In that moment, Hutto felt the same numbness he’d experienced five years earlier when he lost his oldest brother, Jimmy, his best friend and role model. When his wife told him that his brother was dead—an Alabama game warden, he’d been shot during a drug raid—Joey Hutto had shut down for just a second, and then he’d immediately begun focusing on how the death would affect his thirteen-year-old niece, Hailey, Jimmy’s daughter. Now, standing in front of Doneski on this grim afternoon, Hutto went through the exact same process: he became numb, and then all he could think about was Jennifer Bostick and their two girls. Where was Jenn? Did she know yet? Who would be there for her? Were the girls with her?

Doneski gave Hutto twenty seconds to grieve. Then he said, “Joey, I need you to get out there. I need you to take over Bulldog and keep the men together.”

Hutto stayed silent.

“Are you okay?” Doneski asked him.

“I’m fine,” Hutto said. “When do you want me to go?”

“Get your equipment, I need you to get on an aircraft in about twenty minutes,” Doneski told him.

Hutto stepped out of Kolenda’s office. He ran into Kennedy, and the two men embraced. “You let me know what you need,” Kennedy said.

Hutto jogged to his small bedroom, or hooch, to grab his essentials. He knew he had to focus on Bulldog Troop and help its surviving leaders get control of a devastating situation; they and their men were trapped in hell. But he couldn’t stop thinking about Jennifer Bostick and her two daughters. The world seemed a far darker place than it had been just ten minutes before.

Newsom, Faulkenberry, and the other squad leader, Staff Sergeant Ben Barnes, made three trips to the rocks where Bostick had been killed, gathering rucksacks, radios, and GPS equipment. Newsom spotted something shiny in a nearby tree: Bostick’s dog tags, hanging from a branch six feet off the ground. He pulled them down and shoved them in his pocket.

Another exclamation of gunfire rang from across the river, and Faulkenberry staggered forward. He’d been shot. He looked down: his left leg was fine—he was standing up straight on it—but his right had been lacerated and had twisted around, so that his foot was facing almost backward. The leg had essentially been cut in half at the thigh. Faulkenberry’s pants began to fill up with blood, like a sack being filled with water.

“I’m hit,” he announced. He seemed so nonchalant about it that neither Newsom nor Barnes believed him at first. Then Faulkenberry slumped down onto the ground, twisting his leg with him. He was now facing the river.

Newsom and Barnes came over to him. Barnes pulled out his tourniquet and combat bandages and did what he could while Newsom tried to find a vein for an IV in Faulkenberry’s skinny arm. It took him four tries, but finally he got it. RPGs exploded and bullets kicked up all around them, though they didn’t even realize it at the time, so focused were they on patching up their wounded colleague, hooking him up to the IV, and feeding him the “pill pack” of three medications that every soldier carries: a Tylenol-strength painkiller, an anti-inflammatory drug, and a general antibiotic. Faulkenberry’s sciatic nerve—running from his lower back down his leg—had been severed, so the leg was completely numb except for a throbbing pain. Once they’d gotten him relatively stable, Newsom and Barnes helped him hop down the mountain to the convoy and the other troops.

Down on the road, the insurgents were getting closer and the explosions growing louder, and some of the ANA soldiers started to run away. “Hey, motherfucker!” Newsom yelled at one of the fleeing men, “get back over here!” The Afghan stopped and sheepishly looked back at the American officer.

Newsom’s magazines were filled with tracer rounds so he could mark targets for his troops and the low-flying Apaches. “You see what I’m shooting at?” Newsom asked the ANA soldier as he fired into the northern hills. “Shoot there!” He then heard something behind where they were standing, up the mountain to the south and southeast: more insurgents. Time to go, Newsom thought: We have a KIA and WIAs, and those WIAs will soon turn into KIAs if we don’t haul ass.

Enemy fire swarmed around them, the bullets as frenzied and chattering as invading locusts. As wounded American and ANA troops fell to the left and right of him, Newsom told all of those still standing to aim their weapons up the mountain, toward the south, and he himself did the same, crouching and walking back toward the vehicles as he pulled the trigger. Fire was also coming from across the river, to the north, the explosions ferocious from that quarter as well.

Morrow, White, Wilson, and Nic Barnes had by now arrived at the Humvees on the road; they were yelling that Fritsche had been killed. Faulkenberry heard them as he sat, calm and conscious, in the backseat of a Humvee. His gunner, Private First Class Michael Del Sarto, adjusted the bandages that Fortner had applied to the staff sergeant’s wound. Faulkenberry’s mangled right leg was dangling outside the Humvee, and other soldiers, oblivious to his injury and panicking under fire, kept bumping his knee with the armored door. Finally, fed up, he reached out, grabbed his own leg, pulled it and twisted it inside the Humvee, and slammed the door shut. Let’s go, let’s go, I’m going to bleed out, he thought. But the trucks weren’t budging. They couldn’t: bullets and RPGs were peppering the Humvees, seemingly from all sides, and the Americans had little choice but to use the two trucks for cover as they returned fire. (The other two QRF Humvees had earlier pushed down the road to spread out for strategic reasons.) Faulkenberry’s head started feeling heavier. His men kept talking to him, trying to keep him awake. He took off his chest rig, packed with ammo and plates of bulletproof Kevlar, to let up some of the pressure on his body.

“We need to go get Fritsche,” Newsom announced. He attempted to corral several other guys to come with him.

“Fritsche’s dead, sir,” Wilson said. “If we go get him, someone else is going to get killed.” Wilson knew that what he was proposing they do—or rather, not do—was a violation of military protocol, and he hated the notion of leaving anyone behind, but he couldn’t stand the thought of losing another soldier in a recovery effort. Maybe if it’d been some other soldier dead up on that hill—Nic Barnes, for instance—then Wilson would have led the charge to get the body and bring it back… or maybe not. He had all sorts of complicated feelings about his short relationship with Ryan Fritsche, about their time together on that mountain, and about how Fritsche had died. The bottom line was that Wilson just wanted to get the hell out of there, and he wanted the men who were still living to keep on living. Military funerals had protocols, too.

Fortner, meanwhile, had been worrying about what might happen to Faulkenberry if they didn’t get him medevacked out soon; the tourniquet was having only a limited effect. Then the medic heard about Fritsche’s being MIA, and he felt torn. Should he volunteer to mount a recovery effort for a fallen brother? It might come at the expense of Faulkenberry’s life. “We need to leave now, or John is going to die,” Fortner finally told his platoon sergeant.

The Apache attack helicopters continued to work over the enemy positions. The lush forests and rocky landscape made it hard to identify insurgent locations and just as hard to get bombs on top of them, but Roller and his radio man kept feeding coordinates to the pilots of the F-15s and A-10 Warthogs, while the rest of 1st Platoon kept the road clear from their observation post.

The convoy at last began rolling forward.

Newsom ran ahead of the Humvees to keep the momentum going. They were on a road where no cover existed, so there was no sense in their trying to find any: the troops could either shoot and move or stay and die.

Newsom heard a snap and turned to see Private Barba holding his chin, with blood pouring from a hole in his face.

“Sir, I’m shot,” Barba said.

“You’ll be fine,” Newsom said flatly.

As the convoy edged forward—some troops in the trucks, others walking alongside them—a number of soldiers began vomiting, overcome by a combination of dehydration and exhaustion. Along the way, the wounded were dropped off at the landing zone, which offered a modicum of cover from the enemy fire. Private First Class Chris Pfeifer ran up to Faulkenberry’s Humvee with a stretcher. “It’s going to be okay, Sergeant,” he said. “You’re going to be all right.” The kid had a way of projecting eternal optimism, even in the midst of battle and bloodshed.

Del Sarto, the gunner, stuck by Faulkenberry’s side, trying to reassure him. “Here comes the medevac, don’t worry!” he fibbed as a helicopter buzzed in. But Faulkenberry was not so out of it that he couldn’t see and hear and differentiate among the several kinds of birds.

“Shut up,” he told Del Sarto. “I know that’s an Apache.” Medevacs were Black Hawks.

Soon a Black Hawk did arrive. The landing zone was so small that the pilots would have had every right to refuse to land, but they brought the bird down anyway. Faulkenberry and Sultan, the most seriously wounded of the men, were the last to be loaded on so that they would be the first off when they got to Forward Operating Base Naray. Pfeifer and another private put them in, banged the shell of the Black Hawk to give the all-clear, and watched as it flew them out of Nuristan forever.

The makeshift landing zone. (Photo courtesy of Alex Newsom)

The battle was nearly over, but a new commander was finally on his way. Joey Hutto landed at Combat Outpost Kamu and updated Kolenda over the radio: most of the men were now rolling out of the valley, he reported, but Fritsche’s body was still on the mountain; they’d have to send a team to go back and get it. Kolenda and Hutto decided that Roller and 1st Platoon should stay where they were, in a good position to call in bombs and cover whatever force went into the valley to recover the corpse. It was not uncommon for this enemy to ransack or even mutilate any bodies left on the battlefield, and the Americans couldn’t let that happen to Ryan Fritsche.

Hutto headed to Camp Kamu’s operations center, picked up a radio, and prepared formally to assume command.

He froze for a minute.

It was not pleasant, what he had to do: he needed to announce that he was replacing Tom Bostick, his close friend, because he’d been killed. Even though Hutto, as the new commander of Bulldog Troop, had inherited his predecessor’s call sign, “Bulldog-6,” he decided not to identify himself by that right now; he knew that many of Bostick’s troops would be listening, and he was concerned that some of them might not have heard the news yet. It just felt wrong to him—as if by his use of the call sign, he would be not only usurping Bostick’s place but also alerting the men to the loss of their leader in the crassest way possible.

Instead he said simply, “Captain Hutto is now on the ground.” Kolenda, in his first subsequent transmission, welcomed his new troop commander and called him Joey. It wasn’t protocol, but the lieutenant colonel was nothing if not empathetic. He then gave Hutto orders as “Bulldog-6,” and that became Hutto’s name from then on. And this was how many in the field, among them Nate Springer, learned that their friend and commander Tom Bostick had been killed.

In Martinsville, Indiana, Deputy Sheriff Volitta Fritsche, Ryan’s mother, looked out her window and saw several sheriffs’ cars in her driveway. She had taken some time off from her job due to her husband’s illness and death, but she was scheduled to return to work just two days later, so she couldn’t imagine why all her coworkers had shown up at her house.

Then she saw a man she didn’t recognize get out of one of the patrol cars. He was dressed in an Army uniform. After he exited the car, he put on a beret. Her heart started pounding.

“This can’t be happening,” she said aloud.

One of her coworkers knocked on the door. Volitta Fritsche answered it but pointed at the soldier and said, “He can’t come in here!”—hoping that somehow, by denying him entry, she might be able to prevent the inevitable.

The soldier, and another, entered anyway. The one she’d seen through the window informed her that her son had been reported missing in action. The news was devastating, but it also gave her a glimmer of hope.

“What does that mean?” she asked. “Does that mean he’s still alive?”

“The only information I have, ma’am, is what I told you,” said the soldier.

“He could be alive?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“Was he taken prisoner?”

“I don’t know, ma’am.”

“These people have been beheading prisoners,” she said. “Could he have crawled off and be hiding in a cave?”

“Yes, ma’am,” the soldier said. “Anything’s possible at this point.”

After her visitors left, Volitta called her daughter-in-law, Brandi, who had been told the news by a different set of soldiers.

“Where could he be?” asked Brandi, crying.

“He’s probably hiding somewhere in the mountains,” Volitta suggested. “He’s good at that kind of thing. Remember, land navigation is his forte.”

“I know,” Brandi said. “I’m just so scared.”

A few hours later, the soldiers returned to Volitta Fritsche’s home to tell her that they had some new information: Ryan was still MIA, but now they also knew that he had been wounded in action.

“Is he okay?” Volitta asked.

“I don’t know, ma’am,” the soldier replied. “They’re reporting he was shot in the head.”

“I don’t understand,” she said. “If they saw him take a hit, and they’re back to safety, why don’t they know Ryan’s condition?”

“They can’t find him, ma’am.”

“ ‘Can’t find him’? What do you mean, they can’t find him? You mean they left him out there?”

“They said the fighting was so intense, they couldn’t get him out,” the soldier said. “I’m sorry.”

“I thought you guys didn’t leave anyone behind!” Volitta cried. “Ryan wouldn’t have left one of his guys behind!”

The Landay-Sin Valley near Saret Koleh was now teeming with U.S. aircraft, bombing every location that the remaining men on the ground—Roller, primarily—called in. Hutto ordered that bombs be dropped in a circle around the spot where Fritsche had last been seen. Newsom wanted to head back into the valley, but he’d been told by Roller that the higher-ups wanted him to hold off for now; they were devising a plan.

Hutto weighted himself down with guilt over Fritsche’s death. He was the one who’d sent the staff sergeant to 2nd Platoon; he’d even escorted him to the helicopter that would fly him to Combat Outpost Kamu. On that first night of his new command, Hutto got word to Newsom that he should send a quick reaction force to recover Fritsche’s body. A reluctant Morrow went along on the mission, remaining in the Humvee and staying in radio contact with the members of the QRF as they hunted for the corpse.

The searchers couldn’t see much by moonlight, and the bombardment had pulverized most of the rocks into loose gravel, which made climbing even more difficult. When they turned on their white lights, they saw further evidence of bombing and strafing runs from earlier in the day. They found several former fighting positions littered with empty water bottles and, in one case, a soft SAW ammo carrier. Morrow guided them over the radio to the location where Fritsche had been killed.

His body wasn’t there.

Pfeifer, Newsom’s driver that day, sat with the lieutenant in a second Humvee; he was so drained that he kept nodding off behind the wheel. Newsom nudged him every minute or so to wake him up. Each time, Pfeifer would open his eyes and smile: Good to go. The kid was just like that, Newsom thought.

The QRF troops walked down the mountain. Back in their Humvees, they stopped off at the former casualty collection point to pick up some assault packs that were supposed to be there but weren’t. The evening, it seemed, had a theme.

The searchers did find some human remains—skull fragments, almost certainly from Bostick—which they collected in an ammunition can that Morrow held in his lap during the drive back to Combat Outpost Kamu. Otherwise, the QRF returned from the mission empty-handed.

As the sun rose on the Landay-Sin Valley, Roller radioed to Hutto that 1st Platoon needed to head back to Combat Outpost Kamu. He and his men were spent, down to thirty seconds’ worth of ammunition for the 240 machine gun and almost out of water. Hutto gave them permission, but this, too, added to his guilt over Fritsche: after sending him to the battlefield in the first place, he was now approving Roller’s request to leave his body behind there, all alone. And while Hutto believed those who said the kid had been KIA, he hadn’t seen it for himself.

In fact, the hunt for Fritsche’s body had not been abandoned: Kolenda’s boss, Colonel Chip Preysler, committed a different unit from his brigade, the 2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, to conduct another search the next night. Also known as the ROCK Battalion, the unit was led by a contemporary of Kolenda’s, Lieutenant Colonel William Ostlund, who gave the impression that he thought his men were tougher than those who’d already tried to find Fritsche—maybe tougher than anyone, period. Ostlund landed his tactical command post on Hill 1696, overlooking the staff sergeant’s last known location; the ROCK’s Chosen Company landed at Combat Outpost Kamu, where its members were briefed by Hutto and others from 1-91 Cav. Then the seventy or so troops from Chosen Company walked to Saret Koleh. Wilson, eaten up by guilt, joined them. As he hiked the mountain with the Chosen Company troops, the sergeant worried that they wouldn’t be able to find Ryan Fritsche—that perhaps he’d never be found at all. He wondered what the insurgents had done to poor Fritsche’s corpse. The worst thoughts possible ran through his mind.

But the Chosen Company troops did find Fritsche, lying faceup in the very spot where he’d been killed; either he’d been taken away and then returned there by the enemy or the first search party had somehow missed seeing him. He had been stripped of his personal effects and military equipment: his body armor, weapon, and boots were gone. He was wearing just a shirt, pants, and socks. His arms were folded across his chest. His eyelids were closed. An entry wound blemished his left temple, and a matching exit wound showed behind his right ear.

Fritsche was put on a Skedko plastic stretcher and carried down the hill. He was taken to Combat Outpost Kamu, where his remains were officially identified. Three days after Ryan Fritsche was killed, the soldier in his green uniform and Army beret pulled up to Volitta Fritsche’s Indiana home for one final visit, this time to tell her that all hope was lost, and her beloved son—the Little Leaguer and high school basketball center with gifts of determination and beauty—was gone.

Dave Roller was distraught at the loss of Bostick; everyone in Bulldog Troop was. But for Roller, the hardest thing of all was his belief that even as he and his fellow soldiers were out there fighting for their lives, no one back home cared. Ninety percent of the American people would rather hear about what Paris Hilton did on a Saturday night than be bothered by reports on that silly war in Afghanistan, Roller thought. Of this he was convinced. That the people they’d been fighting for would never even know their names made the death of soldiers such as Tom Bostick and Ryan Fritsche all the more tragic.